World Outlook for Nuclear Power after Fukushima

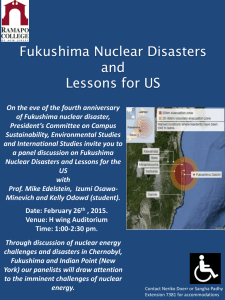

advertisement

World Outlook for Nuclear Power after Fukushima H-Holger Rogner The immediate impact of the Fukushima Daiichi accident The Fukushima Daiichi accident of 11 March 2011 that was caused by a devastating earthquake and subsequent tsunami has re-ignited the debate about the role of nuclear power in the current and future global energy mix. Initial government policy responses, in large part fuelled by sensationalist media reports and public pressure, pointed towards an even more uncertain future of the technology than before. Germany, within weeks after the accident, renounced its September 2010 policy decision to extend the lifetime of its reactor fleet by an average of twelve years and closed for good eight nuclear reactors that were off-line for refuelling, maintenance or repairs. Moreover, an accelerated phase-out of the remaining nine reactors by 2022 was decided upon which corresponds to an average plant-lifetime of approximately 30 years. In order to mitigate the impact of the lower total generating capacity in the country, the government announced a fundamental energy transformation (“Energiewende”) based on renewables and energy efficiency improvements throughout the economy. The German phase-out-path is considered to be the fastest possible way of shutting down the remaining nuclear power capacities without running into critical system instabilities. The Japanese government ordered the shut-down or blocked the restart of most reactors in the country for the conduction of mandatory two-phase stress tests1. They further ceased all construction activities of new builds and decided to decommission the Fukushima Daiichi Units 1 to 4. By May 2011 (two months after the accident), only 26 of the remaining 50 reactors were in operation and this number successively declined to zero on 5 May 2012 when Tomari-3, the country’s only reactor left in operation, was taken off the grid for maintenance and refuelling. Several units that had completed planned maintenance and refuelling outages remained shut down because of public opposition or lack of local authorities’ endorsement of a restart. On 16 June 2012, Prime Minister Noda announced the government’s approval, with agreement of the local authorities, to restart Units 3 and 4 at Kansai Electric Power Company's (Kepco's) Ohi plant in the Fukui prefecture. Both plants were shut down shortly after the Fukushima Daiichi accident for scheduled outages and have since successfully passed phase 1 of the mandatory stress test. After two months without nuclear power in Japan, Ohi-3 started generating electricity again on 5 July 2012 and was followed by Ohi-4 two weeks later. In late May 2011, the government of Switzerland allowed the country’s five existing reactors to continue operating, but without replacement at the end of their service lives of approximately 50 years, with the last reactor going offline in 2034. In September, the Swiss parliament endorsed this long-term phase-out plan. In addition to operating safety concerns and lack of resistance to natural and man-made disasters, the rationale was that new-build nuclear power would lose its competitive advantage due to the added costs associated with new (post-Fukushima) safety and security standards. 1 Phase 1 requires utilities while units are shut down for inspections to examine the safety margins of important reactor components with regard to their ability to withstand beyond design-based earthquakes and tsunamis, and to put in place measure to cope with extended station black outs, etc. Based on the results of these tests, the government will decide whether a reactor can or cannot resume operation. In addition any restart requires a go ahead from Japan’s regulatory organizations and approval from local prefectural governments. Phase 2 of the stress tests will involve a comprehensive safety assessment of all reactors with the objective to enhance the reliability and effectiveness of safety checks. This overall assessment resembles the stress tests carried out in the European Union and elsewhere. 1 In Italy, a referendum, planned before 11 March 2011, on the reintroduction of nuclear power which was abandoned in the late 1980s by a similar referendum, was held in June 2011 and rejected the reestablishment of a national nuclear power programme by a large majority. In November 2011, Taiwan, China, announced a new nuclear energy policy of phasing out nuclear power, however, no specific time frame has been outlined other than: “once their licenses expire” (Taipei Times, 2012). The plants currently under construction will be completed and become operational contingent upon passing all safety inspections. In Belgium in October 2011, the 2003 decision to shut down the country’s oldest nuclear power reactors in 2015, which had been reconsidered in 2009, was reinforced. Moreover, the government proposed a doubling of the special tax on nuclear power paid annually by the nuclear industry. The decision effectively ruled out the building of new nuclear plants in the country. On 23 July 2012, the Belgian government announced the schedule for the total phase out of nuclear power by 2025 complementing the closures for three units announced on 4 July 2012. No particular justification was provided. All Belgian units are to close between 2015 and 2025 which corresponds roughly to a service life of 40 years per unit. Only one unit, Tihange 1, is permitted to operate to 50 years of age; an exception made specifically to avoid blackouts. Other countries pursued a less drastic approach. Clearly, a disaster such as the Fukushima Daiichi accident calls for reflection. In most countries with nuclear programmes, the immediate response to the accident was to conduct comprehensive safety reviews including reassessing the safety margins of nuclear plants of all nuclear installations. In addition, many countries introduced improvements to their frameworks for dealing with nuclear accidents and associated emergency preparedness and communication activities. In addition, many countries revisited their long-term energy development plans and policies and analysed their national energy demand and supply options. In order to enhance nuclear safety, many countries ordered the implementation of stress tests of nuclear power plants to evaluate their capacity to withstand extreme natural and often also man-made events. Measures have been initiated to: improve preparedness for prolonged power blackouts; protect sources of backup electrical power; and to assure the availability of water for cooling, even under severe accident conditions. Emergency preparedness and response capabilities came under critical review, and plans to strengthen these are currently under development. Most importantly perhaps is the radical revision of worst-case assumptions for safety planning. In addition, some countries with explicit intentions to explore the nuclear option or introduce nuclear power to their national energy mixes have announced that they will no longer do so (e.g. Kuwait, Senegal, Venezuela) or that plans will be delayed (e.g., Indonesia, Thailand) while governments continue to reassess their plans for their future use of nuclear power. The impact on the nuclear industry The Fukushima Daiichi accident definitely undermined public confidence in nuclear power. Past experience from the Three Mile Island and Chernobyl accidents have shown that in many countries it will take decades of successful operating experience of the global fleet of nuclear power plants to restore a certain level of public confidence. In the wake of these accidents, the industry improved its overall safety culture, particularly with regard to all operational aspects of nuclear power installations. The memories of the Three Mile Island and Chernobyl accidents eventually faded, in large part due to the demonstrated safe and economic operation of reactors around the world. In addition, during the early years of the 21st century, several issues began to dominate public energy policy debates, namely: mounting concerns about energy security; volatile fossil fuel prices after a long period of stability at low levels; climate change considerations; and continuously rising electricity demand. As nuclear power can play a pivotal role in mitigating all these issues, political and public opinion progressively tilted towards a higher level of tolerance of nuclear technology in many countries. 2 As of 2004, construction starts per year began to rise and reached 16 new builds by 2010 - a level of construction starts not witnessed since 1985 (see Figure 1). All starts since 2000 have occurred in countries with already existing nuclear power plants, with Asian countries taking the global lead (see Figure 2). 50 400 45 350 No. of construction starts 300 35 250 30 25 200 20 150 15 100 10 Total installed capacity, GW 40 50 5 0 1951 1953 1955 1957 1959 1961 1963 1965 1967 1969 1971 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 0 Figure 1: Number of construction starts globally and total installed generating capacity, 1951 - 2012 (30 June 2012). Source: IAEA, 2012a. Before the Fukushima Daiichi accident many countries without nuclear power programmes expressed interest in adding nuclear to their national electricity generation portfolios. This interest varied from country to country. A dozen countries had decided to implement national nuclear power programmes and started preparing the necessary infrastructure. Another seven countries started preparations, however without a final decision. More than 40 countries either considered nuclear power programmes or were interested in obtaining relevant information on the technology and its prerequisite infrastructure requirements. Together with the surge in construction starts in countries with already operating nuclear power plants, this rise in interest in, and popularity of, nuclear power after 20 years of quasi stagnation (except for Asia) was popularly labelled as a “nuclear renaissance”. Construction starts 12 Grid connections 10 0 62 37 10 20 Non-Asia 30 40 50 60 70 80 Asia Figure 2: Construction starts and grid connections since 01 January 2000. Source: IAEA, 2012a. Figure 1 shows the global impact of the Fukushima Daiichi accidents on construction starts. Construction starts in 2011 plummeted to four reactors (although all starts occurred after 11 March 2011) and to one new build so far in 2012. This decline is the result of several factors as several countries suspended new construction permits pending: site re-evaluations and seismic re-qualifications; reactor design reviews especially with respect to withstanding multiple, concurrent external initiating events; and updated safety and regulatory guidelines based on the “lessons-learned” from the accident. However, the preFukushima trend of uprates through reactor component refurbishments and renewed or extended licences for many operating reactors continued in 2011 and the first half of 2012. 3 Nuclear Operating Safety “One of the statutory functions of the IAEA is to establish or adopt standards of safety for the protection of health, life and property in the development and application of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes, and to provide for the application of these standards to its own operations as well as to assisted operations and, at the request of the parties, to operations under any bilateral or multilateral arrangement, or, at the request of a State, to any of that State’s activities in the field of nuclear energy” (IAEA, 2003). The IAEA safety standards establish fundamental safety principles (IAEA, 2006), requirements and measures aimed at the protection of people and the environment against radiation risks by achieving the highest practicable safety levels in nuclear installations. It also involves the control of radiation exposure of people and the release of radioactive material to the environment, restriction of the likelihood of events that might lead to a loss of control over a nuclear reactor core or a radioactive source and the mitigation of the consequences of such events, if they were to occur. A fundamental safety principle is that the prime responsibility for safety must rest with the person or organisation responsible for facilities and activities that give rise to radiation risks, i.e., nuclear facility operators are ultimately responsible for the safety of their facility. Another principle is that an effective legal and governmental framework for safety, including an independent regulatory body, must be established and sustained. National governments, therefore, are responsible for regulations that govern how safety at nuclear facilities is maintained, as well as for reducing radiation risks, including emergency response and recovery actions, monitoring releases of radioactive substances to the environment, and regulating the safe decommissioning of facilities, and the disposal of radioactive waste. Nuclear accidents do not respect borders. Therefore, the primary responsibility of operators and Member States, enshrined in the IAEA Fundamental Safety Principles, must be backed by an international approach to safety. The IAEA, through the Department of Nuclear Safety and Security, works to provide a strong, sustainable and visible global nuclear safety and security framework for the protection of people, society and the environment. This framework provides for the harmonized development and application of safety and security standards, guidelines and requirements. But the IAEA does not have the mandate to enforce the application of safety standards within a country. Safety standards are only effective, if they are properly applied in practice. National regulators, therefore, have a pivotal role in ensuring continued nuclear safety and are encouraged to adopt the IAEA's safety standards for use in their national regulations. IAEA response to the Fukushima Daiichi accident The IAEA responded to the accident by activating the Incident and Emergency Centre in Vienna and organizing specialized expert missions to Japan to gain an understanding of the accident and to provide assistance and expert advice. On 30 March 2011, the IAEA Director General called for a Ministerial Conference on Nuclear Safety to be held in June 2011 to consider the implications of the accident. The objectives of the Conference were to: Undertake a preliminary assessment of the accident; Identify actions needed to strengthen the national and international emergency preparedness and response capabilities; Identify those areas of the global nuclear safety framework that may require strengthening. The Conference adopted a Ministerial Declaration which requested the Director General, inter alia, to prepare an IAEA Action Plan on Nuclear Safety. The 12 point IAEA Action Plan on Nuclear Safety was developed following intensive consultations with Member States (IAEA, 2011). The Plan built on the Declaration by the Ministerial Conference, the conclusions and recommendations of the three conference working sessions as well as other relevant sources. It was adopted by the Board of Governors in September 2011 and unanimously endorsed by all 4 Member States at the 2011 IAEA General Conference. The ultimate goal of the Action Plan is to strengthen all aspects of nuclear safety worldwide. The 12 points of the Action Plan with short annotations are listed in the Annex. Initial calls for a comprehensive and globally binding convention of nuclear operating safety, e.g., mandating all countries with nuclear facilities to adopt and fully implement current IAEA Safety Standards with verification of adherence, were not supported by Member States. Nuclear operating safety remains a national responsibility. Instead, the plan emphasizes voluntary peer reviews of the operating safety of all nuclear power plants as well of the effectiveness of national regulatory bodies. The Action Plan, therefore, is not a blue print for the employees of the IAEA Secretariat. Its success will hinge on the level of ownership adopted by Member States, regulators, nuclear operators, vendors, international and intergovernmental organizations, i.e., it requires inclusive participation and full cooperation of all involved in nuclear matters. Actions, therefore, are explicitly addressed either to Member States, or to the IAEA Secretariat or to other stakeholders, or to all. It should be noted that, operationally, the level of nuclear power plant safety around the world remains high. Safety indicators, such as those published by the World Association of Nuclear Operators (WANO) and reproduced in Figure 3, improved dramatically in the 1990s along with plant performance measured in annual plant availabilities. To a large extent, this attributable to the efforts of regulatory bodies over the years as well as the standards that they have set in design and operation. In recent years, in most areas the situation has stabilized. However, the gap between the best and worst performers is still large, providing substantial room for further improvement. Figure 3: Unplanned scrams per 7000 hours critical (left axis) and load factors (right axis). Source: WANO (2012) Nuclear power today As of 25 of July 2012, the global fleet of nuclear power plants consisted of 435 reactors with a combined installed nuclear generating capacity of 370 GWe (375.5 GWe on 10 March 2011). Note: the total includes plants that currently are off-grid such as the remaining 48 reactors in Japan but not declared as permanently shut down. In 2011 nuclear power accounted for 12.3% of global electricity supply down from 13.5% the year before. Figure 4 (left) depicts the regional distribution of nuclear generating capacities. 5 Global generating capacity: 370.0 GW Latin America Africa 0.9% 0.5% Latin America 3.2% South East Asia 5.3% North America 1.6% North America 28.5% Far East 21.8% Middle East 0.2% Plants under construction: 59.2 GW Eastern Europe/CIS 15.6% Western Europe 27.1% Far East 53.2% Western Europe 3.2% Eastern Europe/ CIS 25.0% South East Asia 14.5% Figure 4: Global generating capacity (left) and plants under construction (right) - as of 25 July 2012. Source: IAEA, 2012a Despite the Fukushima Daiichi accident, the trend of uprates and renewed or extended licences for many operating reactors continued in many countries. Uprates of some 400 MWe and the grid connection of 8 new build reactors (totalling 5.7 GWe since the accident helped mitigate the lost capacities of the 15 reactors (11.4 GWe) declared shut-down for good. The right panel of Figure 4 shows the regional distribution of the 62 reactors currently under construction with a combined generating capacity of 59.2 GW. It highlights the shift in expansion from the traditional nuclear countries in North America and Europe which dominate the current regional capacity distribution to Asia where the long term growth prospects remain centered. Outlook Every year the IAEA develops projections of global nuclear power development derived from a countryby-country ‘bottom-up’ approach. They are established by a group of experts and based upon a review of nuclear power projects and programmes in Member States. The projections cover the period to 2030 with an outlook to 2050. The IAEA estimates should be viewed as very general trends whose validity must be constantly subjected to critical review as energy and electricity demand and the role of nuclear power are subject to economic growth and structural economic change, demographic developments, technology performance and costs, energy resource availability and future fuel prices, and energy and environmental policy. The projections provide a plausible range of nuclear capacity growth by region and worldwide. They are not intended to be predictive nor to reflect the whole range of possible futures from the lowest to the highest feasible. The LOW projection accounts for new builds already firmly in the pipe line including scheduled retirements, planned uprates and license renewals, plus projects in Member States that can be reasonably assumed to materialize. Naturally, the Fukushima accident was on the minds of experts when the 2011 and 2012 projections were compiled. Likewise, the continued financial and economic crises and associated uncertainties affected the projections, especially in the short run. However, the past drivers behind the use of nuclear energy have not changed (population and economic development, environmental protection and climate change, energy security considerations and fossil fuel price volatility) and will continue to fuel nuclear power development. The 2012 projection shows a 90 GWe reduction compared with 2010 - the last projection before the Fukushima Daiichi accident (or 456 GWe instead of 546 GWe for 2030). The longer term outlook to 2050 with 469 GWe is rather modest. The projections reflect a future where replacement investments of retired capacities rather than expansion characterize the nuclear sector 6 after 2030. The absence of growth, however, is consistent with the philosophy of the LOW projection as only few projects can be considered ‘firm’ beyond 2030. Additionally, the LOW projection does not automatically assume that ambitious targets for nuclear power growth in a particular country would necessarily be achieved. These assumptions are relaxed in the HIGH projection which is much more optimistic, but still plausible and technically feasible. The high case assumes that the current financial and economic crises will be overcome in the not so distant future and past rates of economic growth and electricity demand, especially in the Far East, would essentially resume. In addition, the high case assumes the implementation of stringent policies globally targeted at mitigating climate change. The Fukushima impact was a reduction of 63 GWe (down from 803 GWe in the 2010 projection) by 2030. The longer term outlook to 2050 (HIGH) is characterized by a temporal shift of about one decade to the future - a continuation of the delay effect and ‘wait and see’ behaviour regarding the technology in many, especially newcomer countries. In 2010 global nuclear generating capacities for 2050 were estimated at 1415 GWe and about 1110 GWe for 2040. In 2012 the value for 2050 was lowered to 1137 GWe or about the 2010 estimate for the year 2040. Figure 5 displays the historical expansion of nuclear generating capacities and the annual projections for the period 2005 to 2012. For the LOW projections the financial and economic crises since 2008 did not affect the outlook notably and projections still pointed to continued nuclear expansion. In contrast, the HIGH projection was affected by the overall, rather dire global economic, outlook and the successively higher projections since 2005 came to a halt in 2010. 900 850 550 550 525 800 525 500 800 500 750 475 475 700 450 450 700 425 650 425 400 400 600 600 375 375 550 350 350 325 500 500 325 300 450 300 275 275 400 250 250 400 350 225 225 200 300 300 200 175 175 250 150 150 200 200 125 125 100 150 100 75 100 100 75 50 50 50 25 25 0 0 0 0 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 1960 900 800 700 history 2005 600 2007 2008 2009 2010 500 850 800 750 700 650 history 600 2005 2006 500 2007 450 400 300 2011 2012 HIGH projections 550 2006 GW(e) GW(e) GW(e) GW(e) LOW projections 200 2008 400 350 2009 300 2010 250 2011 200 2012 150 100 1970 100 50 0 0 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2020 2030 Figure 5: Development of successive annual projections of total nuclear generating capacities, IAEA LOW (left) and HIGH (right) projections, 2005 - 2012. Source: IAEA, 2012b. After 2010 the Fukushima impact is clearly evident and, in the LOW projection, suggests a delay in nuclear new builds of about a decade and the 2030 projection of 2012 now falls in the range of preFukushima projections for the year 2020. The sharp drop of construction starts in 2011 and 2012 (see Figure 1) is the consequence of the suspension of construction permits in several countries, the renewable directives in many jurisdictions, the emergence of potentially large amounts of relatively inexpensive shale gas and the decline in public acceptance in many countries. The HIGH projections for 2030 show a lower reduction of nuclear generating capacities than the LOW projections in both absolute and relative terms. This is consistent with the HIGH projections’ overall more optimistic outlook on economic development, a new and effective binding international agreement on mitigating climate change and the restoration of public confidence in the technology. Figure 6 shows the projected nuclear capacity developments for major world regions. In both projections, future nuclear development will be centered in Asia. This shift is already well in progress as demonstrated by the location of the reactors currently under construction (see Figure 2). As the momentum is rising to Asia, especially non-OECD Asia, Europe shows the biggest negative difference between the 2011 installed capacity and the LOW projection - a contraction of 41 GWe from 125.8 GWe 7 at the end of 2011 to 85 GWe in 2030. North America (-3.5 GWe) and Pacific OECD (-6.4 GWe) are further regions with a contraction of nuclear generating capacities by 2030. The expansion leaders are non-OECD Asia and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) with 97 GWe and 28 GWe additional nuclear generating capacity. Modest nuclear growth occurs in the Middle East, Africa and Latin America. In the HIGH projection nuclear power capacities expand in all regions, most prominently in Non-OECD Asia which account for 55% (or net 205 GWe) of the expansion alone. Europe and Pacific OECD reverse the negative trends portrayed in the LOW projection and increase their respective current generating capacities by about 30 GWe each. CIS and North America add 42 GWe and 33 GWe while Africa, Middle East and Latin America experience the beginning of a bullish nuclear sector. 800 700 600 GWe installed Middle East 500 Non-OECD Asia Pacific OECD 400 CIS Africa 300 Latin America North America 200 Europe 100 0 2011 2020 (LOW) 2020 (HIGH) 2030 (LOW) 2030 (HIGH) Figure 6: Regional nuclear capacity developments in the 2012 IAEA LOW and HIGH projections. Source: IAEA, 2012b. Conclusion The Fukushima Daiichi accident and subsequent safety reviews and stress tests have significantly affected the global prospects for new nuclear build. The 2012 projections of total nuclear power generating capacity in 2030 is 8-16% lower than before the accident. However, globally, the accident is expected to slow down or delay growth in nuclear power but not to reverse it. On a nation-scale, the impact is more diverse and measures taken by countries have been varied: a number of countries announced reviews of their programmes, some took steps to phase out nuclear power entirely while others re-emphasized their expansion plans. In fact, most countries with nuclear power have reaffirmed their commitment to expanding nuclear power while incorporating the lessons-learned from the accident. In countries considering the introduction of nuclear power, interest also remains high. Of the countries without nuclear power that before the accident had strongly indicated their intentions to proceed with nuclear power programmes, a few have cancelled or revised their plans, while others have taken a ‘wait-and-see’ approach. Most have continued in their pursuit of introducing nuclear power into their energy mixes. The factors that had contributed to the renaissance of interest in nuclear power before the Fukushima accident largely remain the same. Questions about the future of the technology remain. In order to regain public confidence in nuclear power, the lessons learned and those yet to be learned from the Fukushima accident have to be implemented into national nuclear programmes in a timely, transparent and inclusive manner - a process that will extend well into the future. 8 ANNEX The Action Plan 1. Undertake assessments of the safety vulnerabilities of nuclear power plants in the light of lessons learned to date from the accident: Member States assess the design of their nuclear installations against site specific extreme natural hazards and implement the necessary corrective actions. 2. Strengthen IAEA peer reviews in order to maximize the benefits to Member States: Member States incorporate the accident’s lessons into IAEA peer reviews, apply these more broadly to address regulatory effectiveness, operational safety, design safety, and emergency preparedness and response. The results should be made transparent. Member States are also requested to provide experts for peer review missions. 3. Review and strengthen emergency preparedness and response arrangements and capabilities: Member States conduct national reviews of their emergency preparedness and response arrangements and capabilities, with IAEA providing assistance through Emergency Preparedness Review (EPREV) missions. The IAEA, Member States and relevant international organizations (IOs) review and strengthen the international emergency preparedness and response framework encouraging greater involvement of the relevant IOs in the Joint Radiation Emergency Management Plan JREMP). Bolster the assistance mechanisms to ensure that necessary assistance is made available promptly, and fully utilize the IAEA Response and Assistance Network (RANET), including expanding its rapid response capabilities. 4. Strengthen the effectiveness of national regulatory bodies: Regularly review (e.g. through IAEA Integrated Regulatory Review Service - IRRS - missions) of national regulatory bodies, particularly their independence and resources, and strengthen them as needed. The IAEA Secretariat to enhance the IRRS for peer review of regulatory effectiveness through a more comprehensive assessment of national regulations against IAEA Safety Standards. 5. Strengthen the effectiveness of operating organizations with respect to nuclear safety: Regularly review (e.g. through IAEA Operational Safety Review Team - OSART - missions), and strengthen the management systems, safety culture, human resources management, scientific and technical capacities in operating organizations. Each Member State with nuclear power plants is requested to voluntarily host at least one OSART mission during the coming three years, with the initial focus on older nuclear power plants. Thereafter, OSART missions are to be voluntarily hosted on a regular basis. 6. Review and strengthen IAEA Safety Standards and improve their implementation: Improve the effectiveness of the international legal framework and work towards a global nuclear liability regime that addresses the concerns of all States that might be affected by a nuclear accident. Member States implement the IAEA Safety Standards as broadly and effectively as possible, in an open, timely and transparent manner. 7. Improve the effectiveness of the international legal framework (ILF): Improve the effectiveness of the ILF and work towards a global nuclear liability regime that addresses the concerns of all States that might be affected by a nuclear accident. Member States explore mechanisms to enhance the implementation of the Convention on Nuclear Safety, the Joint Convention on the Safety of Spent Fuel Management and the Safety of Radioactive Waste Management, the Convention on the Early Notification of a Nuclear Accident and the Convention on Assistance in the Case of a Nuclear Accident or Radiological Emergency and consider proposals made to amend the Convention on Nuclear Safety and the Convention on the Early Notification of a Nuclear Accident. Member States work towards establishing a global nuclear liability regime that addresses the concerns of all States that might be affected by a nuclear accident with a view to providing appropriate compensation for nuclear damage. Member States give due consideration to the possibility of joining the international nuclear liability instruments as a step toward achieving such a global regime. 8. Facilitate the development of the infrastructure necessary for Member States embarking on a nuclear power programme: Help countries planning to start a nuclear power programme to create an appropriate nuclear infrastructure based on the IAEA Safety Standards. Member States are encouraged to voluntarily host Integrated Nuclear Infrastructure Reviews (INIR) and relevant peer review missions, including site and design safety reviews, prior to commissioning the first nuclear power plant. 9 9. Strengthen and maintain capacity building: Member States with nuclear power programmes and those planning to embark on such a programme strengthen, develop, maintain and implement their capacity building programs, including education, training and exercises at the national, regional and international levels; to continuously ensure sufficient and competent human resources necessary to assume their responsibility for safe, responsible and sustainable use of nuclear technologies; and to incorporate lessons learned from the accident into their nuclear power programme infrastructure. 10. Ensure the on-going protection of people and the environment from ionizing radiation following a nuclear emergency: Member States, the IAEA Secretariat and other relevant stakeholders facilitate the use of available information, expertise and techniques for monitoring, decontamination and remediation of both on- and off- nuclear sites and the IAEA to consider strategies and programmes to improve knowledge and strengthen capabilities in these areas; to facilitate the use of available information, expertise and techniques regarding the removal of damaged nuclear fuel and the management and disposal of radioactive waste resulting from a nuclear emergency; and to share information regarding the assessment of radiation doses and any associated impacts on people and the environment. 11. Enhance transparency and effectiveness of communication and improve dissemination of Information: Member States, with the assistance of the IAEA Secretariat, strengthen the emergency notification system, and reporting and information sharing arrangements and capabilities; to enhance the transparency and effectiveness of communication among operators, regulators and various international organizations, and strengthen the IAEA’s coordinating role in this regard, underlining that the freest possible flow and wide dissemination of safety related technical and technological information enhances nuclear safety. The IAEA Secretariat facilitates and continues sharing with Member States a fully transparent assessment of the accident at TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, in cooperation with Japan. The IAEA Secretariat and Member States, in consultation with the OECD/NEA and the IAEA International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale (INES) Advisory Committee review the application of the INES scale as a communication tool. 12. Effectively utilize research and development: To conduct research and development in areas highlighted by the accident, such as extreme natural hazards, management of severe accidents, station blackout, loss of heat sink, spent fuel accidents, and post-accident monitoring systems in extreme environments. References IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency), 2003. Fundamental Safety Principles: Safety Standards Series No. NS-R-3, Vienna, Austria. IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency), 2006. Fundamental Safety Principles: Safety Fundamentals, IAEA Safety Standards Series No. SF-1, Vienna, Austria. IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency), 2011. IAEA Action Plan on Nuclear Safety. Vienna, Austria. IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency), 2012a. Power Reactor Information System. http://www.iaea.org/pris. Vienna, Austria. IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency), 2012b. Energy, Electricity and Nuclear Power Estimates for the Period up to 2050, 2012 Edition. Reference Data Series No. 1 (RDS-1/32). Vienna, Austria. Taipei Times, 2012. Nuclear power phase-out plan confirmed. 15 May 2012. http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2012/05/15/2003532872 WANO (World Association of Nuclear Operators), 2012. Performance Indicators 2011. London, United Kingdom. 10