Atomic Bomb Debate - Mounds Park Academy Blogs

advertisement

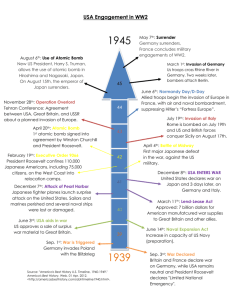

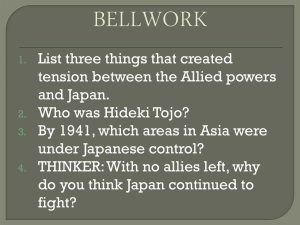

Atomic Bomb Debate We will have a debate about whether or not the United States was justified in using the atomic bomb to end the World War II with Japan. Specifically, our resolution or decision will be: Resolved: The United States was justified in dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. To prepare for the debate you will need to read the short description that I gave you of the decision to use the atomic bomb. Then, I want you to read the following pieces of evidence. You will notice that there is evidence for and against the resolution or decision. To begin with I want you to be familiar with both sides of the debate. For each piece of evidence, you should write the main point or idea the author is trying to make. You are also welcome to underline important facts, add extra notes in the margins, etc., but you must write the main idea for each paragraph. You will use these notes as your preparation for our class debate. Affirmative Evidence (in support of the decision) Arguments for why it was justified to use the atomic bombs 1. James Turner, historian, October 2005 The first reason the bombing was justified was that it was the most viable way to force the Japanese to surrender. The Allied offer of the Potsdam Conference on July 26, 1945 stipulated that the war would end only when the Japanese surrendered and gave up Emperor Hirohito. This offer was completely unacceptable to the Japanese, who, at the time, regarded their emperor as a god. President Harry S Truman was in a situation where he could not change the terms of the offer, because the American citizens wanted Hirohito imprisoned, if not executed. Changing the terms of the offer would also be regarded as a sign of weakness on the Americans' part, which was unacceptable during a time of war. Main Idea: 2. Ed Quillen, Columnist, The Denver Post, August 9, 2005 Suppose Truman had foregone the bomb, and ordered the invasion. It likely would have meant at least a year of bloody, brutal fighting. He ordered the Hiroshima bombing. Nagasaki followed, in accordance with military plans but without specific presidential orders. One more bomb was available, but Truman forbade its use without his express permission, for he was horrified by its effects. Japan surrendered on Aug. 14. Truman made the right decision in accordance with his first priority - minimizing American casualties while forcing Japan to surrender. Main Idea: 3. Mahmood Elahi, writer, Ottawa Citizen, August 12, 2005 pg. A11 The official U.S. position on the decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was that it averted an invasion of Japan and saved countless American and Japanese lives. Given the fact that the Japanese forces were involved in the mass murders of people they subjugated and were stubborn fighters prepared to resist any invasion, dropping the atomic bombs might have truly saved millions of American and Japanese lives.” Main Idea: 4. Henry L. Stimson, Secretary of War for Truman, Harper’s, Feb. 1947 We estimated that if we should be forced to carry this plan [to invade first Kyushu and then Japan's main island of Honshu] to its conclusion, the major fighting would not end until the latter part of 1946, at the earliest. I was informed that such operations might be expected to cost over a million casualties, to American forces alone. Additional large losses might be expected among our allies, and of course, if our campaign was successful and if we could judge by previous experience, enemy casualties would be much larger than our own. Main Idea: 5. Max Boot, Olin Senior Fellow in National Security Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York, LA Times, August 3, 2005. These criticisms rest, it seems to me, on a profoundly a historical assumption: that there was something unusual about what happened to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It's true that the atomic bombs were, by many orders of magnitude, the most powerful explosives ever employed. But the havoc they caused, with a combined death toll of over 100,000, was far from unprecedented. By the time the Enola Gay took off, at least 600,000 Germans and 200,000 Japanese had already been killed in Allied air raids. Conventional explosives had reduced all of the major cities of both countries to rubble. In the end, no more than one-third of the total Japanese deaths from air raids — and just 3.5% of the total land area destroyed — could be attributed to Fat Man and Little Boy. Main Idea: 6. Physicist Luis Alvarez, as cited by Gerald Parshall, writer for U.S. News and World Report, U.S. News and World Report, July 31 1995. "This terrible weapon we have created may bring the countries of the world together and prevent further wars. Alfred Nobel thought that his invention of high explosives would have this effect, by making wars too terrible, but unfortunately it had just the opposite reaction. Our new destructive force is so many thousands of times worse that it may realize Nobel's dream." Main Idea: 7. James R. Van de Velde, a member of the U.S. Naval Intelligence Reserves, Political Science Quarterly, Autumn 1995. It really is bad history to isolate one brutal act from terrible war and play "was this event really necessary?" games. The war, like all wars, was a terrible tragedy. Yet there is no way to know what all the ramifications would have been had the Americans suddenly slowed the pace of the war and attempted to effect a surrender from Japan through a siege strategy of the home islands. Maybe such a change would have emboldened the Japanese. Further, while the Americans waited, Chinese, Koreans, Russians, British, and South Asians would have continued to die daily in large numbers while the war dragged on in the larger Pacific theater. Main Idea: 8. David W. Koeller, historian, June 1999 The atomic bomb could very well be the most terrible thing that ever invented. It is a weapon of destruction. When first tested with only thirteen pounds of the explosive, the bomb left a crater six feet deep and twelve hundred feet in diameter as well as causing a sixty foot steel tower to literally disappear. This test, which occurred in New Mexico, was visible from two hundred miles away and could be heard up to forty miles away. Main Idea: Negative Evidence Arguments for why it was NOT justified to use the atomic bombs 1. Dwight D. Eisenhower, General, the White House Years, July 1945, page 18 The United States Strategic Bombing Survey, after interviewing hundreds of Japanese civilian and military leaders after Japan surrendered, reported: Based on a detailed investigation of all the facts, and supported by the testimony of the surviving Japanese leaders involved, it is the Survey's opinion that certainly prior to 31 December 1945, and in all probability prior to 1 November 1945, Japan would have surrendered even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war, and even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated. Main Idea: 2. Duncan Anderson, Senior lecturer at Sandhurst’s War Studies Department, BBC news, June 22 2005. Joseph Grew - America’s last ambassador to Japan before the war started - claimed that Japanese diplomats had been trying to open surrender negotiations with the United States via the then still neutral Soviet Union. These were overtures that the Truman administration knew about, thanks to decrypts of Japanese diplomatic codes, but which they nevertheless chose to ignore. Main Idea: 3. Leo Szilard, Physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project, Wikipedia If the Germans had dropped atomic bombs on cities instead of us, we would have defined the dropping of atomic bombs on cities as a war crime, and we would have sentenced the Germans who were guilty of this crime to death at Nuremberg and hanged them." Main Idea: 4. Gar Alperovitz, Author, The Decision To Use The Atomic Bomb, November 30, 1996. In his memoirs Admiral William D. Leahy, the President's Chief of Staff--and the top official who presided over meetings of both the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Combined U.S.-U.K. Chiefs of Staff--minced few words: [T]he use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender. . . .[I]n being the first to use it, we . . . adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make war in that fashion, and wars cannot be won by destroying women and children. Main Idea: 5. Sandeep Mehta, writer for the Chicago Tribune, August 30, 2005 (Chicago Tribune, ER: 9-7-05, DWO) Finally, the two atomic bombs killed almost 250,000 civilians. Shouldn’t every possible means be tried before making a decision that results in the horrific death of so many civilians, including women and children? The fact the Japan started the war at Pearl Harbor is not a valid argument since it did not target civilians. The atomic bombs wiped out two entire cities. It seems unimaginable that there was no better option. Targeting of civilians should not be justified in any situation, in any war. By justifying the dropping of the atomic bombs, we are doing just that. Main Idea: 6. Ronald Takaki, professor of ethnic studies, Hiroshima Why America Dropped the Atomic Bomb, 1995 The decision to deploy the bomb was made within a larger context than just the war against Japan. The utter obliteration of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and then Nagasaki three days later did, in fact, bring the Pacific War to an end. But, as historians Gar Alperovitz and Martin Sherwin have amply documented, the decision was also related to postwar concerns- the reality of Soviet expansion in Eastern Europe as well as in Asia and more important, the fearful prospect of an atomic arms race. Main Idea: 7. Ronald Takaki, professor of ethnic studies, Hiroshima Why America Dropped the Atomic Bomb, 1995 For the United States during the years between Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s atomic bombing of Hiroshima, there were two wars- the European war and the Pacific war. In Europe, the enemy was identified as Hitler and the Nazis, not the German people. In the Pacific, on the other hand, American anger was generally aimed at an entire people- the “Japs.” During the war, the Japanese were condemned as demon, a monkey race, savages, and beasts. **Note: The terms “Japs” is very racist. The author uses it to help the reader understand the time period. You should NEVER use this term to refer to the Japanese people. Main Idea: 8. John W. Dover, Elting E. Morison Professor of History at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Technology Review, Sept 1995. The heroic narrative similarly fails to question the need for the atomic bombing of Nagasaki on August 9, which occurred before Japan's high command had a chance to assess Hiroshima and the Soviet entry. Indeed, even many Japanese who now accept that Hiroshima may have been necessary to crack the no-surrender policy of Japanese militarists maintain that Nagasaki was plainly and simply a war crime. Main Idea: 9. The Bombings killed many, and caused many to suffer long after the explosion Lindsey Anhalt, The Atomic Bomb—A study of aftermath December 2000 On August 6, 1945, a fifteen-kiloton atomic bomb ignited the center of Hiroshima, Japan, instantly killing more than 100,000 people, and injuring hundreds more. Three days later, a second atomic bomb exploded over Nagasaki, resulting in 70,000 additional deaths (Marston 13). Not only did the atomic bombs dropped by the United States kill thousands of Japanese and demolish two major cities, but they spawned serious medical implications on both the survivors and future generations. For months after the explosions, in addition to the severe burns covering most of the victims’ bodies, survivors developed symptoms that puzzled doctors, such as blood cell abnormalities, high fevers, chronic fatigue, diarrhea, vomiting, hair loss, and depression. “Radiation sickness” and “Acute Radiation Syndrome” were terms used by doctors to describe these various symptoms in survivors that surfaced a few months later, sometimes within hours, after the blasts. Moreover, years later doctors noticed an increase in the incidence of cancer among the survivors Main Idea: Other Notes or Evidence: