File - K & G Museum for Graduate Studies

Nicholas Africano

Rejecting Illusion in Painting

Throughout history, painting has been an outlet for artists to produce a picture on a two dimensional plane. It gives an artist an opportunity to become a creator, a conjuror of images that give rise to a particular narrative, express an emotion or even change the way the viewer sees the world. Figurative painting throughout history has been a way for an artist to connect as directly to painting the experiences of human life as possible. In the past, figurative painting has been a way to create the illusion of reality, or in other words, show a depiction of what life was like in some regards. Much of the time, figurative painters used several conventions that produced these images, such as a specific narrative, creating an illusion of space, using particular brushstrokes and separating the image from the world by putting it in a frame.

In the 1970’s the New Image painter, Nicholas Africano, rejected the traditions of Figurative painting by acknowledging certain parameters of painting within his work such as showing the flatness of the picture plane as well as rejecting the illusion created by painters in the past. In the book published by the Whitney

Museum, New Image Painting, Richard Marshal discusses this new way of painting,

“Familiar adjectives used to describe an artistic style- representational, figurative, realist- do not differentiate these artist’s way of using images nor adequately convey the distinct painterly qualities manifested in the work.” (Marshall, Pg 7) The

1

differences between Africano (as well as other New Image painters) and traditional figurative painters is that he uses those painting conventions mentioned above and changes how they are utilized in the work. The way in which he tells a story is different from that of Edward Hopper. He depicts space much differently than

Leonardo DaVinci or Richard Diebenkorn and his flat yet detailed paint handling and method of framing the story with a color field within his work is greatly different than the way traditional frames attached to a painting after the fact are used in art in the past. It is through these means that Nicholas Africano not only acknowledges a history of painting but also shows his opinion on what a painting actually is. Along with other figurative painters of the past, his work is an image in paint on a plane that tells a story, but through the way he paints, the image isn’t necessarily the only important part of the painting; it is both the image and the fact that it is a painting that are important.

Narrative:

When looking at paintings from the Renaissance to Modernism, works almost become a window into a familiar world. Those paintings create a sort of voyeuristic dialogue between the viewer and the painting, where the viewer is outside of the frame of the painting looking into a two-dimensional world created by the artist.

The viewer feels like they could walk into that space, the only thing separating them from the painting is the knowledge that this painting is not real but one that contains the illusion of being real.

2

An extreme example of this is Edward Hopper, who often physically incorporates a window into his paintings, but even when he doesn’t he paints the point of view and a distance away from the figures to appear as though they are being watched by the viewer from a safe, yet voyeuristic, distance. Nighthawks

(Plate 1) is Hopper’s masterpiece depicting a scene of people sitting near the window of a restaurant. The important part of the scene, which is the interactions between the figures, is painted from a distance at eye level. This implies that the viewer functions as a person in the painting viewing the characters dining from a distance. The painting is about five feet long, and the edges of the painting, when viewed at a particular distance, act similarly to periphery vision, placing a blurry vignette around the scene, acting like a window into Hopper’s world.

What is also happening in Nighthawks is that Hopper is referencing a specific moment in time. When a viewer looks at that painting, the viewer does not say, “that person in the booth is me.” More than likely they would think, “Perhaps I have seen this before,” or maybe “this references a specific time and place.” However, it is hard to place yourself within that specific painting and get to the conclusion that this is about your experience and not the painter’s experience. This reinforces the idea that the painting is a window into another world, that because the painter’s experience of this scene, be it from his imagination or from observation, is separate from what is true of the viewer’s own personal experience. The viewer is even more prominently on the other side of the window, looking in.

3

What Africano is doing in his work is essentially the opposite. He is not painting a window into another world; he is painting human experience. Africano, has stated,

“I had been a writer of short, non-discursive prose. I was trying to make a direct and immediate image and began to substitute small drawings for words within the writing…It is important for me to work from the specific to the general, to focus on a highly specific moment of an experience – and allow that to become more generalized through another person’s response.”

(Marshall 14)

Africano essentially removes all the information that is not necessary and leaves just human interaction. Insulin (Plate 2) is a painting about Africano giving his father a shot of insulin. Despite that painting being about a very specific event in

Africano’s life, the way in which he paints this event gives the viewer the opportunity to insert themselves as one of the characters painted. Removing the ground and painting it as a color field means the viewer is not going to reference a specific time or place. The figures are painted generally and small enough that the viewer wouldn’t likely reference specific people as the characters in the painting.

The difference between the figures in Hopper’s painting and those in Africano’s paintings is that Hopper’s figures seem to be iconic signs; they resemble specific people while Africano’s figures are indexical of people, that they indirectly reference a specific person (such as Nicholas Afrciano and his father) but they could be anyone because of how those characters could seem so relevant to our own experience.

This rejection of using a specific narrative in Africano’s work, as opposed to generally referencing a moment in human experience, ties into semiotics as well.

4

Hopper’s iconic image of those specific people at that specific restaurant in that specific location is trying to replicate a specific place and time; it is almost trying to act like a photograph. Hopper is using his own lighting and colors to interpret the scene, but he is so directly referencing that moment that it feels like it is only once removed from reality; it is the illusion of reality. Africano’s paintings are signifying a human experience, but like an abstract painting, not directly copying its reference.

Instead they make the viewer aware of their two-dimensionality by flattening the picture plane and really focusing in on the fact that those figures are painted onto a canvas and not copied onto one. He removes the background, which eliminates a reference to a time and place. Africano also inserts a color field as ground, which simulates space, even though it isn’t. Those factors force the viewer to read the painting not as a mirror of reality, but one that signifies it.

There are times that Africano’s 1970’s paintings stray away from that, when he starts to starts to work more symbolically. For example, The Scream (Plate 3) is ostensibly a painting of a man comforting a friend after a tragic death, but what

Africano actually shows is himself dressed in women’s clothing comforting another version of himself. In this case, I am not as quickly able to insert myself as one of those characters because the scene feels more specific to Africano’s experience.

However, because I can see the connection between the appearances of the two characters, I am able to understand the story behind the painting a little better.

Africano is still stepping away from a direct copy of reality and therefore creating his own interpretation of reality in the same language as the other works. He is

5

taking more command of the viewer than his previous works; he is not giving the viewer as much of an opportunity to relate to the narrative.

Spatial Illusion:

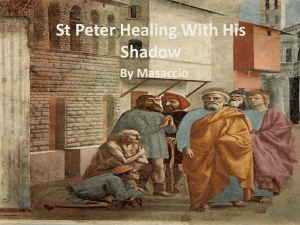

Since the Middle Ages, painters have utilized illusory tools to create normative spaces within the picture plane such as isometric perspective, linear perspective and atmospheric perspective. In the 15 th century, the Italian artist

Brunelleschi was the creator of what artists today know call linear perspective; however, other forms of perspective were used much earlier prior to and during the

Middle Ages such as isometric perspective or shifting the scale of figures to show relative distance. These tools were developed to create a more realistic space, and therefore a more believable scene. In Marianne Marcussen’s “Perspective: Then and

Now, and Artistic Practice” she discusses the desire to master perspective through history. She states, “This widespread interest in perspective can be explained by its potential to be a basis for the creation of images and the fact that its illusionary qualities have proven easy for onlookers to accept, both in art works and when other kinds of topics are illustrated.” (Marcussen, 73). Artists utilized these techniques, linear and atmospheric perspective to achieve this believable space and achieve the effect as mentioned before, a window into another world that the viewer could accept as an extension of their own.

Atmospheric perspective, probably most famously displayed in Leonardo da

Vinci’s Mona Lisa, (Plate 4) is achieved through the use of color and brushwork. Da

Vinci, when creating the background behind the portrait of Mona Lisa, utilized lower

6

intensity colors and the blurring of edges to create the illusion of distance. The sky directly behind the Mona Lisa fades from a darker brighter blue closest to the top of the picture plane to a lighter, yellower, duller color as it recedes back into space. The same can be attributed to the ground of the painting. Darker, brighter colors are placed directly behind the image of the Mona Lisa and shift back into lighter, duller more faded colors as spcae recedes in the distance.

The Mona Lisa also creates the illusion of space compositionally in a similar method to other Renaissance paintings. The painting itself is broken into thirds, with a figure sitting as the foreground. The Mona Lisa’s hands, which from elbow to elbow make up the bottom third of the painting, act as the area closest to the viewer spatially. Atop that is the second third of the painting, which acts as a middle distance between the foreground and the horizon line. The top third of the painting sits the furthest back in space, along the horizon line.

The Bay Area Figurative first generation painters were a group of artists living in the Bay Area of California who rejected the purity and non-representational aspects of Abstract Expressionism for a new approach to painting. Richard

Diebenkorn’s, Cityscape I (Plate 5) utilizes both methods of perspective mentioned above, atmospheric and linear, though not as clearly as the Mona Lisa. Diebenkorn clearly is sitting on top of a hill or building when painting Cityscape 1 in order to provide the aerial view. If we were to line up the lines of the buildings and roads, we would find that Diebenkorn’s eye level is slightly higher than the picture plane, indicating that Diebenkorn is looking down at the landscape. Diebenkorn blurs the lines on the buildings at the top left corner of the painting and uses duller, lighter

7

colors than those at the bottom; this is not unlike Da Vinci’s strategy in the Mona

Lisa. He is also flattening shapes and colors at the top and puts more brushstrokes at the bottom of the painting, giving the emphasis to the portion of the painting that is closer, spatially to the viewer. This is shows that Diebenkorn clearly was educated in painting and knows how these tools were used historically. However, he is selectively picking how he uses these tools. He is not rejecting them, unlike the New

Image Painters do. Africano is not utilizing atmospheric or linear perspective in his paintings. Instead, he generally paints fields of color using simply a flat plane of color. There is nothing that alludes to atmosphere; the space is simply not defined.

In Nicholas Africano’s paintings, the relationship between the figures is the most important aspect; this is only emphasized by the vast field of color. The color field does not recede in places or become more prominent in others; it remains one flat plane in which the characters in the painting play their roles. What this does is make the viewer even more aware of the fact that the painting is indeed a painting.

The two-dimensionality reinforces the figures as being shapes of color on a flat surface as opposed to the illusion of a real person on a picture plane. The figures are essentially floating in space, in color. In New Image Painting, Marshall writes about

Africano’s work, “Because of their isolation and alteration, they create a distance between themselves and the viewer” (Marshall, 8) The only space that Africano implies is that between the viewer and the figure, and between the figures to the edge of the picture plane. That nothingness around the figures not only isolates the narrative from the rest of the painting, but that color field also forces the viewer to disregard their surroundings in the real world and focus in on the painting itself.

8

When one looks at a painting like Nighthawks or the Mona Lisa, if one focuses in on a portion of the painting, lets say a face, the illusion of the space is still there in one’s peripheral vision, one is only getting closer to it. When you walk closer to an

Africano painting, your peripheral vision is enveloped by nothing but color and you are therefore only able to focus on the narrative itself. This is not at all like reality; humans cannot perceptually eliminate the rest of the world when focusing on an object. They can only choose to ignore.

Brushwork:

Mark making or paint handling are terms used to describe the way that the artist approaches the surface of the picture plane. Those terms cover a great deal of ground in the painting world. Those terms can relate to using texture in painting or making flat planes of color, to blending so that the image looks photographic.

Paintings of the Renaissance up through much of the 19 th century, the process of painting was not evident in the strokes of the painting. For example, in the Mona

Lisa the painting is done through thin layers of paint blended together to produce a smooth surface (Plate 6). What this does is create the illusion of smooth skin, rolling around the bones of the face. When one looks at the surface of the painting, one would not know which portion was painted first, an eye, a mouth, or the background. Each part is so smoothly blended, it appears that the whole painting happened at once.

This is, however, not typical of the whole history of painting. Fauvist painters used planes of color as well as heavier brush strokes to indicate changes in plane,

9

light and space. The painting, Self-Portrait in the Studio, by Andre Derain (Plate 7) is a Fauvist painting where light is shown through brush strokes that are brighter and more intense than darker, duller spots. Each spot of color is made up of a brush stroke or a field of brush strokes that define the space. Marks are made to show the shifts in light and each mark is plainly visible. This is something not uncommon to

New Image painters. Neil Jenney, a contemporary of Nicholas Africano, utilizes this tradition of heavier brushstrokes in his paintings however, the intention is different.

In his painting, Threat and Sanctuary, (Plate 8) each brush stroke is visible, but not to show the shift of light and color. Jenney’s intention is to acknowledge the picture plane. Each mark that he uses makes the canvas look flatter showing the viewer that his painting is no illusion.

Africano, however, is utilizing really none of those methods to paint his image. He is not creating this illusory space by hiding is brushstrokes. He is using strokes to show differences in planes of a face or space. He isn’t even using paint how Neil Jenney is, but his intentions as Jenney are similar. Africano’s marks are utilitarian. Each mark is meant to essentially indicate an object. In the close up photograph of Insulin, (Plate 9) the chair that Africano’s father is seated on is made up of four thin brush strokes. The viewer knows that that is a chair despite not having the indication of light source or any other illusory information typically provided. Africano’s shirt, similarly, is created by a variety of different brush strokes, though each stroke is indicating the pattern on his shirt, not showing how that shirt could appear in space. In Africano’s color field, there are seemingly no

10

brushstrokes at all. This flatness acknowledges the ground as being a single flat plane. The flat, overall colored plane is recognizes the flatness of the picture plane.

Africano does utilize some illusory methods in his painting practice. There is an indication of light source and change of plane occurring in the pants of the figures in Insulin. He also is adding differentiation of skin tone within the arms of those figures and taking some time to show differences in facial features by using differing brush strokes. Those marks within the faces, however, are relative to showing a portion of the narrative. Africano’s repetitive marks on his father’s arms and neck signify the wrinkling skin of an older man. Each repetitive mark is acting like

Jenney’s ground in Threat and Sanctuary in that they are not alluding to atmospheric space or change of light. Those marks are just there, however, in Africano’s case, they are contributing to the overall narrative as well.

The Frame:

Taking framing into consideration has been something that has been relevant to painting for hundreds of years. The frame’s purpose, traditionally, could show the status of the collector, add to the decoration of the room, and become the symbol of art. In Jean-Claude Lebensztejn’s 1988 article, “Framing Classical Space,” he discusses the relationship of the frame to the painting and the painting’s relationship with the surrounding world. In the article, he quotes a letter written from Poussin to his patron, Chantelou concerning the framing of his painting:

“Once you have received your painting, I beg you, if you think it a good idea to adorn it with some framing, for it needs it; so that when gazing at it in all its parts,

11

the rays of the eye are retained and not scattered outside in the course of receiving the especes of which, being jumbled with the depicted things, confuse the light [or the space: confondent le jour].

It would be very fitting that the said frame be gilded quite simply with mat gold, for it unites very sweetly with the colors without clashing with them.”

(Lebensztein 37)

What Poussin is asking, and Lebensztejn is talking about is both the request to separate the painting from the rest of the room by framing it out, almost cleaving it away from its surroundings, but also to adorn it in a way that it doesn’t detract from the painting. Though, perhaps a seemingly obvious request that a frame not take away from the beauty of the painting and separate it from other, lesser paintings, the fact that this 17 th century artist is defining this concept of framing is quite remarkable.

The New Image painter, Nicholas Africano, was indirectly dealing with the concept of framing. His works, though not framed by traditional wooden frame are dabbling with those two concerns written in Poussin’s letter. Poussin requests that the frame be put there to separate the work from the other paintings in the room, but also one that does not detract from the painting itself. Africano employs his own frame within the picture plane without having to attach a wooden frame after the fact. His paintings are framed by using that vast color field to separate the narrative within the work from the rest of the world. In Insulin, the narrative occurring sits directly in the middle of the canvas. The distance from the back of Africano’s father’s chair to the edge of the picture plane is similar to, if not equal to the distance from

Africano’s legs to the other edge this is occurring as well on the top and bottom of

12

the paintings. The distances from the painted narrative to the edge of the picture plane are relative to the size and shape of the painted narrative, similar to a mat board or framed print where the mat would replicate the dimensions of the print but create the space between the print and the wall. The color field is acting like this space to separate the wall from the narrative. Regarding Poussin’s second request that the frame not detract from the painting, Africano eliminates the gilded gold and ornate decorative frame and replaces it with that space. The color neither adds nor detracts from the narrative but gives that sense of importance to the painting that collectors and patrons were seeking by adding extra room. That color field emphasizes the narrative by pointing to it; it says, “This is what you’re supposed to be looking at.”

Utilizing another sort of frame is not unique to Africano; artists who use tromp-l’oeil could paint a frame directly onto a canvas, presenting the illusion of a real frame that is not at all there. Also there are artists who specifically choose to not use a frame at all which as mentioned by Lebensztejn , “A frame always serves as physical evidence that the painting is never self-sufficient,” and so an artist may choose to utilize the dimensions of the canvas as the frame itself, or the profile off the wall as frame. In Africano’s case, however, his paintings have produced the illusion of a frame without having a physical frame or the illusion of one. The paintings don’t need the frame, because they imply having their own.

13

Conclusion:

Without question, using illusion in painting is still something that Western painters utilize extensively. Those traditional methods of painting, though perhaps not glazing over a grey scale image, are still taught at the foundations level. Linear one point and two point perspective is one of the first things learned in Drawing

101. Atmospheric perspective is taught both in color theory and in landscape painting classes. In every museum one visits, lining the walls are gilded and decorative frames adorning paintings.

It is Africano’s knowledge of the history of painting that influenced his works of the 1970’s. As a part of the revival of painting at that time, through the incorporation and rejection of the techniques and traditions of figurative painting,

Africano questioned why certain conventions were used in painting. Africano’s concerns at that time are questions that painters today are still contending with:

Why is illusion in painting necessary and how does rejecting that illusion change the meaning of painting? The answer, of course, is to question what the intention of the piece is. Similar to Poussin’s letter, how would a frame benefit or detract from the work. How would changing use of brushstrokes tell a different story? In the case of

Nicholas Africano, his intention was to make paintings that told a story and despite not having given all the extra information, those stories could be read clearly by a large audience. Through rejecting the traditions of painting, Africano’s story was told, and made paintings that recognized what exactly a painting is, pigment on a flat surface.

14