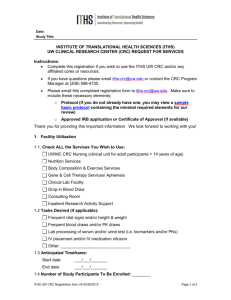

CRC Handbook

advertisement