Translation and Norms.

advertisement

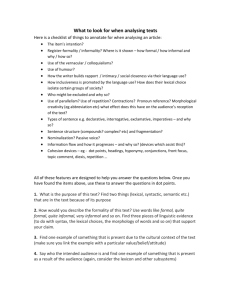

1 IN SEARCH OF TRANSLATIONAL NORMS THE CASE OF SHIFTS IN LEXICAL REPETITION IN ARABICENGLISH TRANSLATIONS1 … as hard as one might try, it is impossible to reproduce networks of lexical cohesion in a target text which are identical to those of the source text. (Baker, 1992:206; italics added) 1. Introduction The objective of this chapter is twofold: (a) to try to arrive at some preliminary generalizations concerning the norms which govern the type and direction of translation shifts in the area of lexical repetition; and (b) to illustrate the above attempt by analyzing and discussing an English translation of an Arabic literary text. I shall therefore be specifically addressing the issue of how lexical chains in Arabic texts are rendered in English; the basic argument postulated being that every translation is bound to result in shifts both in the type and size of lexical repetition. The high level of tolerance of lexical repetition in the Arabic culture is reflected in the texture of its texts by the important rhetorical and textual roles assigned to this phenomenon. By the same token, lexical repetition seems to be almost always functional in the Arabic literary polysystem. Conversely, English rhetoric discourages lexical repetition and tolerates it only when motivated and used as a figure of speech (cf. Johnstone, 1991: 4 and Hatim, 1997: 32). This textualcultural discrepancy between Arabic and English is expected to have a 1 This paper was first published in babel, volume 52, number 1, 2006, pp. 39 – 65. 2 bearing on both the translation processes and their products whenever the two languages are involved. Various studies of texts translated from different source languages have tentatively revealed that avoiding lexical repetition seems to be a common translational norm (see, Ben-Ari 1998:2). Besides being worthwhile in themselves, translation studies like these can contribute to translation theory by providing a testing-ground which may lead to the validation, refutation, or –as is mostly the case-, to the modification of these theories. It would, therefore, be illuminating to find out if this postulated repetition-avoidance policy, just mentioned above, applies to Arabic-English translations and, if so, how it is actually implemented by means of different translation shifts. The present study would also attempt to arrive at viable explanations of the norms which determine these shifts 1.1. The nature and role of translational norms Norms, in general, represent conventional, social standards –or models- of acceptability of behavior which are shared by the members of a certain culture. Translational norms, in particular, embody the general values and expectations of a given community at a given time regarding the correctness and appropriateness of both the process and the product of translation (cf. Toury, 1980: 51). Thus, it becomes evident that it is not only the two language systems involved in translation that are exclusively, or even- mainly, responsible for forming and formulating translated texts. Rather, it is the dominant conventional norms, especially those of the target pole, which intersubjectively play a pivotal role in moulding a model for regulating translation phenomena. This can help explain the high level of regularity of translational phenomena which are observed, described, and explained in the translated texts in a given TL and culture. The credit goes to Gideon Toury and Theo Hermans for bringing the ‘concept’ of norms to the forefront in translation studies today. A 3 translated text is no longer considered as a product of ‘transcoding linguistic signs’ but rather as ‘retextualizing’ the SL-text (see Shäffner 1999: 3), so as to make it ‘acceptable’ within the norms framework of the TT-culture. The teleological nature of translation in the TL and its culture is hence emphasized. Besides, every translation can be seen as involving a polar opposition of two sets of norms: those of the source text and culture and those of the goal. Consequently, translations are bound to exhibit traces of both poles. Translation scholars therefore differentiate between two types of basic norms: ‘adequacy’ norms, those of the source, and ‘acceptability’ norms, those of the target. Another distinction made is that between ‘preliminary’ norms and ‘operational’ ones. The former refer to the translation ‘policy’ in a given community whereas the latter govern the translator’s decisionmaking process which operates during translating. The regularity of prevalence of different translational norms has also been found to vary in translated texts. Consequently, some translation scholars, like Toury (1995:67), also distinguish between: ‘basic’ or ‘primary’ norms, viz. those which are so common as to be almost mandatory for a certain translation phenomenon; ‘secondary’ norms which are favorable and common but not mandatory; and ‘tolerated’ or ‘permitted’ which are not common but operative. More types of norms have been suggested by other scholars, but what all taxonomies share is that the study of norms, notwithstanding nomenclature, has almost become an indispensable prerequisite for the study of translated texts. Finally, it would also be necessary perhaps to point out that conflicting and opposing sets of norms may be observed to operate simultaneously, and side by side, sometimes. Complete coherence in the application of translational norms is therefore not to be taken for granted. In fact, instances of deliberate departures from expected norms can often be detected in translated texts. Such departures are, however, usually motivated by stylistic considerations and need to be observed and examined both by translators and translation scholars (cf. Hatim and Mason, 1997: 54). It is essential also to keep in mind that 4 any departure from the norms, be those of the ST or the TT or others, is bound to result in translation ‘shifts’; as discussed below. 1.2. Translation ‘Shifts’ or ‘Transpositions’ In a pioneering article entitled “Translation Shifts” published in 1965, J.C. Catford presents us with one of the earliest systematic discussions and taxonomies of the linguistic phenomena of shifts in translated texts. In his article, Catford defines shifts as “departures from formal correspondence in the process of going from the SL (source language) to TL (target language)” (Catford 1965, in Venuti ed., 2000: 141). He then classifies shifts into two main types: (a) level shifts and (b) category shifts. To the former belong all the shifts which occur in translation between the two linguistic levels of grammar and lexis, such as when one language resorts to lexicalize what is grammaticalized in another; as is done sometimes in Arabic when rendering the English aspectual components of the present progressive or perfect verb structures. Four sub-types of category shifts are also listed; the most common of which is perhaps ‘class shifts’. These occur when translation equivalents in two languages belong to two different grammatical classes; such as, for example, when the ‘adjective’ in the English phrase ‘medical student’ is rendered in Arabic by a ‘noun’. Vinay and Darbelnet’s book, Sylistique comparee du francais et de l’anglais, represents yet another, even earlier, attempt than Catford’s to describe and classify shifts in translation. The book was first published in French in 1958, but was not translated into English until 1995 when it appeared under the title of Comparative Stylistics of French and English: A methodology for translation. In their book, Vinay and Darbelnet use the term ‘transposition’ instead of ‘shift’ and define it as a translation procedure which “involves replacing one word class with another without changing the meaning of the message” (p.36). It thus becomes obvious from this definition that Vinay and Darbelnet’s concept of ‘transposition’ is not as 5 comprehensive as that of Catford’s ‘shift’, since it is limited to only one of the latter’s subsystems; viz., that of ‘class shifts’ just mentioned above. The broader definition of ‘shift’ above, as well as its limited one, restricts its scope to ‘formal’ changes due to differences in the linguistic systems of the two languages involved in the translation process. Yet, it would be safe to maintain that a translated text does not only, not even –mainly, exhibit micro-linguistic changes. The translation process also entails various macro-linguistic shifts; those in lexical repetition being one example thereof. These latter type of ‘shifts’ are not strictly due to differences between the SL and TL ‘systems’ as such, but rather to the different textual and discoursal norms of the two cultures which these languages belong to. As a result, the study of translation shifts has taken on a broader scope lately so as to incorporate linguistic as well as textual/cultural changes in translated texts. Besides, shifts –even in their microlinguistic sense- are no longer to be seen as departures from the SL alone. Rather, translated texts are assumed to exhibit deviations, viz. non-correspondence, when compared both to the SL as well as to the TL. The teleological nature of a translated text can best be appreciated by the fact that the very existence of such a text is actually realized, first and foremost, in the target language and culture in which it is now written and by whose readers it is read (cf. Toury, 1995: 24). Even so, however, neither the linguistic nor the textual correspondence can be full between the translated text and the TL language and culture, since each and every translated text seems to carry along with it some ‘finger-prints’ from its ST. This binary nature of translated texts is aptly portrayed by Toury when stating that such texts which are produced in a certain target language both “occupy a certain position, or fill in a certain slot, in the culture that uses that language” as well as “constituting a representation in that language/culture of another, preexisting text in some other language, belonging to some other culture” (in Schäffner ed.,1999: 20). Translated texts have consequently come to be widely 6 considered as representatives of a special text-type, among many others, within the TL polysystem. Deviations from the TT and those from the ST are still unable, on their own, to cater for and explain all the linguistic and textual shifts in translated texts. Descriptive Translation Studies has revealed that many translated texts, regardless of their STs and TTs, clearly share some common linguistic and textual features among them (see BlumKulka 1986, for example). Consequently, it would be safe to conclude from such recurrent observations that such features shared by ‘unrelated’ translated texts are attributable to the translation process itself, viz. that they reflect some sort of translation ‘universals’. One such ‘universal’ candidate, for example, is the high level of explicitness observed in translated texts as a result of the translators’ common strategy of explicating information stated implicitly in the source text; the phenomenon which has led to postulating the so-called ‘Translation Explicitation Hypothesis’ (see Baker, p.212; Blum-Kulka, p. 300; and Toury 1980: 60; among others). It would thus be tenable, based on the above discussion, to maintain that shifts in translated texts are of three major types: (a) SL-, or adequacy-induced, (b) TL- or acceptability-induced, and (c) translation process-induced. Before concluding this section on the various types of translation shifts, it also seems worthwhile to distinguish between ‘obligatory’ and ‘optional’ shifts. The first are due to some differences between the linguistic systems of the SL and the TL, as when the translator has no alternative but to shift from one word-class to another (as was discussed under ‘class shifts’ above). Such shifts, because of their regularity, are also considered part and parcel of the study of norms in translation studies although they are rule-governed. Optional shifts, on the other hand, are still considered more significant since they indicate and better reflect the choices translators actually make during the translation process. Consequently, comparative translation studies, like the present paper, usually focus on non-obligatory shifts. 7 2. Research corpus and methodology The research corpus consists of an original Arabic text and its English translation. The Arabic text, by a Jordanian writer, is a short story of about five pages which has been translated into English by a reputed American literary translator. 2 A literary text has been chosen for analysis since lexical repetition in such texts is usually highly motivated and has more functional value than in other text-types (see Lotfipour 1997: 190). For the sake of analysis, the source text (ST) was thoroughly examined for all chains of lexical repetition. A lexical repetition chain (henceforth, LRC) is made up of at least two occurrences of the same 3 word repeated in a given text, regardless of whether the repetitions occur within the boundary of one sentence or in separate sentences (see, al-Khafaji 2004). Only open-system ‘lexical’, and not ‘functional’, words can make up such chains. Consequently, every single lexical word in the analyzed text had to be manually checked against all other such words in the text so as to detect all instances of lexical chains. Once this laborious and time-consuming task was over and all LRCs were sorted out and recorded, a comprehensive reference table was then worked out. The table, a sample of which is reproduced below, lists all the constituents of each chain starting with the initial item, in the order they actually occur in the ST text. The full version of the following table comprises 97 LRCs as the total number of chains found in the analyzed Arabic text. The longest 4 LRCs consist of 11 The Arabic short story is entitled ، مائدة، ثالثة مائدتانby Badr Abdul Haqq. It was first published in an anthology of Jordanian short stories by the Ministry of Culture in Jordan in 1992. The English translation, by Nancy Roberts, appeared in A Selection of Jordanian Short Stories, published in Irbid, Jordan, in 1996, pp. 1 – 9. 3 Members in a lexical chain are considered to belong to the ’same’ word when they are repeated (a) with no formal change at all; or (b) with only slight ’morphological’ changes like those of the past-present tenses in verbs or the singular-plural number in nouns; or (c) with ’grammatical’ changes that only affect the word-class, like verb-noun-adjective-etc (see al-Khafaji 2005 for more details). 2 8 lexical words each while the number of lexical constituents in the other LRCs of the text ranges between 2 to 10 words. LRC in the sample Table below, for example, comprises four constituents only. The following text portion is reproduced in order to show the textual environment in which these four constituents of this particular LRC actually appear in the ST (underlining is mine): نعم ،حدث شئ رهيب :لم تذهب سلوى بعيدا ،بل انتقلت الى مائدة مالصقة للمائدة التي كنانجلس اليها، وضعت حقيبتها على سطح المائدة ،وجلست على المقعد ،ومدت يديها الى يدين ،لشخص ما، كان يجلس وحيدا ،منذ البداية ،وشرعا في الحديث على الفور ،حتى لكأنهما يستأنفان الحديث الذي كان يجري بيني وبينها ،كانت سلوى تقول ذات الكلمات التي اعتادت ان تقولها لي ،حتى بريق عينيها ،كان صوبة نحوي منذ ذات البريق ،وذات النظرات الحارة الصادقة التي اعرفها ،والتي كانت م ّ لحظات ،وبدا األمر ،كما لو انها انتقلت من مائدة اجلس اليها ،الى مائدة اخرى ،اجلس اليها انا ايضا ،او شخص آخر ،خرج من داخلي للتو ..................... ياسيدي ومعلمي ،ما عالقة مالمح الشخص اآلخر بالمسألة . ...................... نعم ،نعم ،كانت مالمحه تشبه مالمحي ،لوال فارق العمر ،لقلت انها كانت تشبه مالمحكانت ايضا ،كان صوته ،وكانت ثيابه ،وحركات يديه والقلق المرسوم على خطوط وجهه، تشيه صوتي وثيابي ،وحركات يدي وقلقي .لكنه كان شخصا آخر . . Once the comprehensive table is full and ready, cross-textual alignment is embarked on by thoroughly examining the TT text for the translation counterpart of each and every LRC in the original source text. The objective here is to establish translation relationships between TT-ST text portions which bear on the translation 9 phenomenon at hand. It might be necessary to point out that the question of equivalence and tertium comparitionis, often raised in linguistic comparisons between the LRCs of the ST and their corresponding translation counterparts in the TT, is considered here to have been taken for granted and already established by the very fact that the two stand as translation counterparts to each other; i.e. that translation correspondence presupposes equivalence (see Toury 1980:115). When the translational counterparts between the source and target texts LRCs have been established, the TT ‘solutions’, viz. TT counterparts, are then mapped on their corresponding ST ‘problems’, viz. origins, so as the translation relationships are carefully examined, described, and classified. In the present paper, what we are specifically looking for in this translation comparison are mainly translation shifts, as represented by departures away from the ST. In other words, our interest lies in finding out relevant instances of textual reformulation conducted by the translator which make the translation deviate from the norms of an ‘adequate’ translation and adopt the standards of an ‘acceptable’ translation. Table 1. The first ten LRCs of the ST Serial No. Initial Item Other components in the Lexical Chain ؛ غمامة 1 الغمامة 2. ؛ حزن حزين؛ الحزن؛حزينا؛للحزن؛حزنا؛حزينا؛الحزن؛حزينا 3. ؛ سوداء السوداء؛ السوداء 4. ؛ أدري أدري؛ أدري 5. ؛ أدركت أدركت 6. ؛ وجودها موجود ؛ تجد 7. ؛ صورة صورة؛ تصور؛ صور 10 8. ؛ الذاكرة أذكره؛ تتذكر؛ التذكر؛ ذكرياتنا 9. ؛ تدور أدارت ؛ الشخص شخص؛ الشخص؛ شخصا 10. Section 3 of the paper presents categorized samples of translation pairings which illustrate various translation relationships, as far as lexical repetition is concerned. Each corresponding TT-ST pair of text fragments is also followed by a brief description of the translation shifts implemented by the translator. At the end, an attempt is made towards the interpretation of these shifts in light of the different norms which are believed to have triggered them. Thus a paradigm of shifts together with their possible causes is set up. More general conclusions are later drawn from this paradigm. It is important to keep in mind that throughout the stages of TT-ST mapping as well as the description and classification of shifts, it is the non-obligatory shifts which have been focused upon; since it is this type of shifts which is postulated to be the true representative of norms. Two other things may be noteworthy before concluding this section: (1) Although distributional statistical considerations are usually essential for the study of norms in general, and although frequency figures have been worked out and reported in the study for the various types of shifts in lexical repetition detected in the data, no use of statistical formulas is deemed to be truly informative here since the study corpus is rather small in size. (2) No normative evaluation has been attempted throughout the discussion of different translation relationships either since the present study is not concerned with translation assessment; rather, it is an empirical descriptive study. 11 3. Results of data analysis The process of mapping TT text portions on their corresponding ST fragments which contain LRCs has revealed the following types of shifts as having been implemented by the translator during the translation process. These shifts are presented below in accordance with their frequency of occurrence as found in the analyzed corpus. A brief description and some representative examples are given for each. The cited examples are extracted from the corpus and reproduced below with the minimum accompanying co-text required. The relative frequency of each shift in the analyzed data as a whole is also reported. 3.1. Synonymy Shifts As the rubric indicates, this type of shift entails changing a TT synonym, which has already been used in rendering an ST repetition, to another. It has been found from the results of data analysis that this is the commonest sort of shift: constituting 36 instances out of a total of 98 shifts, viz. 37%. The shift from one synonym to another in the rendering of the members of a ST lexical chain can be understood as part of the translator’s search for cutting down the level of lexical repetition in the TT by resorting to an alternative means of lexical reiteration, other than repetition. It is perhaps worth noting here that lexical reiteration in text can be realized in a variety of means; the most important thereof are lexical repetition, synonymy or nearsynonymy, a superordinate, or a general word (see Halliday and Hasan: 278). Thus, in the following ST-TT pair of text portions extracted from the corpus: (1) a. ... أو شخص آخر خرج... وكذلك أخرج أنا 12 b. I’m exiting too … or to another person who has just now emerged from … one can see that the translator has chosen to translate the second constituent in the above Arabic lexical chain (henceforth; ALC) fragment, i.e. خرج, by the lexical synonym ‘emerged’ rather than by a form of its other synonym ‘exit’, which has already been used. It is also worth pointing out that this is not an obligatory shift since the synonymous English verbs are interchangeable in this context and no obligatory rules of the TL seem to have motivated the shift. As already mentioned above, this kind of shift has been abundantly executed in the study corpus. Sometimes, the translator has been found to shift more than four instances of lexical repetitions to alternative synonyms throughout the translation of a single ALC. The following example is illustrative of one such multiple shifting: (2) a. ... أنت حزين والحزن ال بد أن يكون له سبب... غمامة حزن سوداء تطبق على صدري ال... ً منذ أجيال وأنا أعيش حزنا ً متصال... ما الذي حدث ليجعلني حزينا ً الى هذا الحد؟ . لو كنت أعرف لما كنت حزينا ً الى هذا الحد، أنا ال أعرف.تسألني لماذا b. … …there’s been a black cloud of sorrow weighing heavily on my chest You’re sad. And sadness has to have some sort of cause … What happened to make me feel such anguish? … For generations now I’ve been experiencing a grief that seems never to come to an end… Don’t ask me why. I don’t know. If I did, I wouldn’t be in such a distress. 13 The lexical repetition chain which consists of the total recurrence of the Arabic noun ‘ حزنsadness’ and the partial recurrence of its derived adjective ‘ حزينsad’ has been rendered in English by five formally different, viz. morphologically unrelated, lexical items which are synonyms or near-synonyms to the Arabic ST words. Notice also that while the Arabic ST above exhibits lexical variation in its lexical chain, by using the noun form and its morphologically-related adjective form of the same lexical root, the English TT resorts to a more drastic variety by using five different synonymous words. One can conclude from examining the translation product in 2b above that the translator must have sensed and appreciated the important textual function in the ALC of the word ‘ حزنsadness’ and its derivatives. The recurrent use of this lexical item depicts and reflects the dominant climate of depression and dejection prevailing in the short story; which the above extract comes from. As a result, the translator must have felt bound to preserve this literary atmosphere in the translation. She must have, nevertheless, also equally been under the pressure against rendering such an excessive use of lexical repetition at such a close distance in the TT. The result has consequently been a compromise between the two opposing poles of retention or deletion; this is achieved by the use of multiple synonymy, as shown above. 3.2. Deletion Shifts The second most common shift detected in the translation of ALCs has been found to be the deletion in the TT of an ALC-constituent found in the ST. A total of 19 instances of this sort of translation shifts were found in the TT. In the translation of the following ALC portion, for example: (3) a. .الذي حدث؟ نعم سأروي ما حدث 14 the translator has opted to delete the second occurrence of the verb ‘ حدثhappened; took place’ and thus rendered the above ST text portion as: b. What happened you ask? Alright, I’ll tell you. The translator could have of course retained the lexical repetition in the second ST sentence above, and produced instead: What happened you ask? Alright, I’ll tell you what happened. But she opted otherwise and deleted the repetition in the translation.4 In two other ALCs, the translator has performed this translation strategy three times in each. The following is the relevant text-portion extracted from one on these ALCs: (4) a. ... بل انتقلت الى مائدة مالصقة للمائدة التي كنا نجلس اليها،ًلم تذهب سلوى بعيدا . انها على األرجح مائدة واحدة، ال يتسع اال لمائدتين أو مائدة واحدة... انه مقهى صغير The ALC portion quoted above contains 5 repetitions of the Arabic lexical item ‘ مائدةtable’, out of 11 such repetitions in the whole lexical chain used in the full ST text. In the TT translation equivalent of the above ALC, however, the translator has opted to delete 3 of the five lexical repetitions while leaving the others intact. Consequently, the translation of 4a appears as follows in the English TT: 4 As a textual phenomenon, cohesive linkage by ellipsis in text has been aptly discussed and demonstrated by Halliday and Hasan (1976, 1992: 143). 15 (4) b. Salwa didn’t go far away. All she did was move over to the table right next to ours … It’s a small coffeeshop … there’s only room for two tables…or just one. Yes... it probably won’t accommodate more than just one. It may be worth pointing out again that the deletion of the 3 lexical repetitions of ‘table’ is not dictated by the grammatical rules of English, i.e. it is not obligatory. It remains, however, to try to detect what factors, other than grammar, could have motivated the translator to opt for the deletion shifts above. In an attempt to shed some light on this type of shift, viz. deletion of repetition, it is probably necessary to point out that in all of the instances cited above the deleted lexical items remain easily retrievable. In other words, what the translator has actually done does not obliterate all traces of the ST’s deleted words but, rather, to make implicit in the TT some explicit instances of lexical repetition of the ST. Consequently, in her attempt to minimize the level of recurrent repetition in the TT, the translator has used another alternative linguistic means available to her to achieve this. Shifts discussed in both Section 3.1 and in this section can be, therefore, considered as two different, yet complementary, means towards attaining the same goal; viz. that of reducing lexical repetition in the TT. 3.3. Paraphrasal Shifts This translation shift consists of opting for rendering one or more ST lexical repetitions by a paraphrase translation counterpart in the TT. A total of 13 such instances were detected in the analyzed data. Two STTT text-portions are reproduced below to illustrate this. 16 (5) a. لقد كنا أنا وسلوى نجلس في المقهى الصغير الذي اعتدنا الجلوس فيه... ً حسنا لشخص ما كان يجلس، وجلست على المقعد ومدت يديها الى يدين... منذ سنوات .وحيدا b. You see .. Salwa and I were sitting in the little coffeeshop which for years had been a favorable haunt of ours … and took a seat. Then she reached out and placed her hands in those of someone who, … had been sitting there alone. The above ALC-portion contains four instances of lexical repetition of the verb ‘ يجلسsit down’ and its derivatives. The translator, however, has only translated two of these occurrences, viz. the first and the last above, by a corresponding form of the verb ‘sit’. For the second and third occurrences in the ALC, the translator’s decision was not to repeat the lexical item ‘sit’ but rather to use a synonymous paraphrase for each instead. In order to do so in the second occurrence, الجلوس, she resorted to paraphrasing the whole adjectival clause in which the lexical item occurs. This is an example where shifting lexical repetition can eventually involve larger syntactic units in text. As for the third instance of lexical repetition in the ALC above, the verb جلست was paraphrased by the phrase ‘took a seat’, instead of the use of the equally possible alternative, ‘sat’. Two other instances of such shift can be seen in the translation of the following ALC-portion: (6) a. ً لشخص ما كان يجلس وحيدا... لكني أحذرك منذ البداية... سأبدأ بمحاولة التذكر .منذ البداية 17 b. I’d start trying to remember … However, I warn you ahead of time … of someone who, from the time we’d come in, had been sitting alone. In the TT text-portion, the translator could have preserved the lexical repetition of the second and third occurrences of the Arabic verb يبدأ “start’ by opting for ‘from the start’ for both. She has chosen instead to render each of them by a translation counterpart which involves no lexical repetition of the verb ‘start’. Before concluding discussion of this type of shift, one last point seems in order here. The similarity between translation shifts by using synonymous paraphrases, discussed in this section, and those of shifting by the use of single synonyms, discussed earlier in Section 3.1, should not pass unnoticed. Both types of shifts make use of synonymy as a translation strategy for not repeating an item in a lexical chain. From a statistical perspective, these two similar types together constitute 49 shifts, out of a total of 98 found in the analyzed ST text. Shifting by synonymy thus makes up 50% of all renderings of ST repetitions in the TT. This is undoubtedly a markedly high percentage that is worthy of special attention later in the study. 3.4. Partial Lexical Repetition (Variation) Many cases have been detected in the TT corpus where the translator has chosen to retain and repeat some or all instances of the ST lexical chains. This must be due to the translator’s appreciation for the significant rhetorical role this lexical repetition plays in the text. Consequently, she decides to acknowledge lexical repetition in such instances and announce it in the TT. Even in these cases, however, a marked tendency has been observed to introduce some minor changes in the form of the various occurrences in a given lexical repetition 18 chain. Such formal changes, subsumed here under the rubric of ‘partial repetition’ or ‘variation’, would include adding to a word in a lexical chain, or deleting from it, one or more inflectional or derivational morphemes like changing its tense or number or part of speech, for example. Thus, while the lexical repetitions of a given LC are full repetitions of each other in the ST, that LC, or parts of it, is retained in the TT by formal variants like the ones mentioned above. Some examples from the corpus are cited below. They are followed by some relevant translation notes. (7) a. ... أحتاج أن أرى على وجهه انني كنت أرى في وجهه مالمح خاصة وغامضة . حادة واضحة،ذلك الصدق الحارق كانت مالمح وجهها تشبه مالمح وجهك انت b. I’d detected certain extraordinary, mysterious features in his face … I need to look into his face and see that burning honesty. Her facial features -- like yours-- were vibrant and intense. In the example above, the repetition of the lexical word ‘ وجهface’ in 7a is highly functional in the ST text since it depicts psychological disturbances resulting from the exaggerated and distorted significance that the protagonist in the analyzed short story attaches to the facial expressions of people around him. The translator must have realized this, consciously or subconsciously, and hence comes her decision to retain and announce the repetition so as to be able to convey its textual function and rhetorical impact to the TT readership. Having said that, the translation ‘universal’ of aversion to excessive lexical repetition in general, as discussed in the Introduction, can still be seen to operate even in cases like these. Consequently, and instead of repeating verbatim the four instances of ‘face’ in the TT, the translator has converted the word-class of one of them from a noun to the adjective 19 ‘facial’. Moreover, she has deleted the fourth instance by producing the elliptical phrase ‘like yours’ instead of ‘like your face’. Two more illustrative examples from the study corpus are reproduced and briefly discussed below: (8) a. b. . هناك من يطاردني ويريد قتلي... تدور حول اشخاص يريدون قتلي... … of people wanting to murder me … There’s someone hot on my heels who wants to take my life. (9) a. ، نعم، نعم.كانت مالمح وجهها تشبه مالمح وجهك انت حادة واضحة ... كانت مالمحه تشبه مالمحي b. Her facial features – like yours—were vibrant and intense. Yes, yes … he did look like me. In 8b above, the translator has also introduced variation in the TT by choosing two different verb forms of ‘want’ for the ST’s literal repetition of the verb يريد. By the same token, we can understand the translator’s motive for the variation between the TT’s ‘like’ and the phrasal verb ‘look like’ in 9b. 20 3.5. Expanding ST Repeated Word(s) Another means utilized by the translator in order to alleviate excessive lexical repetition is both to simultaneously retain and expand the repeated words. By performing this type of expansion shift, the translator would both try to preserve the textual function of the repeated word while still avoiding the ‘undesirable’ consequences of literally repeating the same word in the translated text. A shift like this would thus represent a happy marriage between the need to maintain the ST functional units of text (i.e. textemes) and the requirements of TT norms in translation, both as a process in itself and as a product in the TL and its culture. The following three ST-TT text fragments can serve, from among many others in the corpus, as representative of this type of translation shifts. (10) a. أال يكفي ذلك لكي تعرف سلوى؟، حبيبتي أنا.. انها حبيبتي... انت ال تعرف سلوى . حتى بريق عينيها كان ذات البريق وذات النظرات الحارة الصادقة التي أعرفها- b. You don’t know Salwa … Isn’t it enough for Salwa to be my sweetheart for you to know who she is? … Even the twinkle in her eyes was the same, with the same passionate, earnest glances that I’d come to know so well. The high textemic value of the repetition of the word ‘ يعرفknow’, as a token for the great importance which ‘knowing’ Salwa means to the protagonist in the story, exercises heavy pressure on the translator in the direction of retaining the three repetitions of this ST verb. Yet, the translator has given vent to her feelings of uneasiness with the frequent literal repetition by expanding the third repetition of the ST verb ‘know’; thus rendering the one-word verb أعرفهاby the less-repetitive 21 word-group, ‘I’d come to know so well’. It is to be noted, however, that this expansion yields no extra meaning since the meaning of the added words is in fact implicitly embedded in the original source text. It is also worth noting that this explication of what is stated implicitly in the text is the other side of the coin of the strategy of making implicit what is explicit in the text, as already discussed under ‘Deletion Shift’ in 3.2. This same strategy which serves the purpose of avoiding literal repetition by explicating what is implicit in the ST can also be seen in the following short extract of the corpus: (11) a. كان مدرسا ً للرياضيات.... b. …, my school mathematics teacher In the above example, the translator has expanded the ST’s مدرسto TT’s ‘school teacher’ instead of ‘teacher’ only. In Arabic, the mutual reference of ‘ مدرسteacher’ and ‘ مدرسةschool’ is taken for granted by the common root, viz. س-ر-‘ دDRS’ (teach/learn). No such explicit morphological relatedness exists in English between the two words ‘teacher’ and ‘school’, however. In light of this, the translator’s decision to add the word ‘school’ to ‘teacher’ can be understood as yet another example of a translation strategy of evading literal repetition by explicating in the TT some information which is implicit in the ST. In the same vein, the translator in the third example below invests on this translation strategy of expansion so as to avoid literal repetition: (12) a. ...أحتاج أن أرى على وجهه ذلك الصدق الحارق انني أراه كل يوم،ًوأنا أعيش حزنا ً متصال 22 b. I need to look into his face and see that burning honesty … I’ve been experiencing a grief that seems never to come to an end. I’ve seen it everyday. In this case, the translator has opted to translate the first Arabic verb أرىby ‘look …and see’, rather than by ‘see’ alone. The difference between ‘look’ and ‘see’ in English can be explained by the degree of personal involvement reflected by each of them. Similar to the difference between ‘hear’ and ‘listen’, the verb ‘see’ is less purposeful and less pre-determined than ‘look’ in ‘look and see’. The choice of the latter by the translator is thus a reflection of her understanding of the degree of the personal involvement between the speaker in the text and the teacher in the story. The expansion shift thus serves, in addition to avoiding literal repetition, to explicate what is understood by a careful reading of the ST text, at least from the translator’s own perspective. This translation strategy of explicitation has been found to be a common denominator in translated texts in general, as already mentioned in 1.2 earlier, and is considered by many translation scholars as a tentative translation universal (see Blum-Kulka). 3.6. Shifting by Pronominalization In cases like these, the translator uses a pronoun in the TT to replace a noun which enters into a lexical chain in the ST. A total of 5 such instances have been detected in the 98 shifts. The following are sample examples: (13) a. كانت مالمح وجهها تشبه... نجلس في المقهى الصغير، أنا وسلوى- لقد كنا خطفت سلوى حقيبتها السوداء الصغيرة وشبت.. وفجأة.. مالمح وجهك أنت … على قدميها 23 b. Salwa and I were sitting in the little coffeeshop … Her facial features –like yours- were … Then all of a sudden … she grabbed her little black handbag and jumped to her feet… Despite the fact that the TT text-fragment above contains 3 possessive pronouns for the 3 ST pronouns which refer to Salwa, the translator has chosen to replace the second occurrence of the proper noun ‘Salwa’ by yet another pronoun. This case of pronominalization must have been prompted by the translator’s own conviction that this shift would lead to no functional loss. In other words, the textual function of the repetition of ‘Salwa’ in the above ST fragment would not, according to the translator, be impaired by the pronominilization process. This assessment by the translator may have been enhanced by the predominance of pronouns referring to Salwa even in the ST itself. Thus, the translator’s decision to minimize lexical repetition, without compromising its textual function, can be understood. Another example of this type of shift can be found in the following ST-TT extracts: (14) a. b. ... ما عالقة الشخص اآلخر بالمسألة. خرج من داخلي للتو، أو شخص آخر... … or to another person who had just now emerged from in-side me … what does his face have to do with it? Here we have another example of replacing a noun by a pronoun. This time, however, the replaced noun is not a proper noun, as in 13 above, but a common noun. As a result, the translator’s tacit argument, for not having caused any damage to the textual function of the lexical repetition by this shift, may even be more convincing in this case. Thus, resorting to the above shifting, among others, provides the 24 translator with another means yet in her incessant pursuit to avoid or alleviate lexical repetition, especially that of the literal and closedistance type. Although such shifts might lead to reduced textual explicitness, the translator seems to be convinced that they do not jeopardize the overall textual function. 3.7. Adding Extra Repetition(s) A shift like this appears to be an anomaly at first sight. Contrary to the usual translation practice seen so far, which is generally unfavorable to lexical repetition, the translator herself adds one or more repetitions in the TT this time. Examples of such translation shifts are considered ‘marked’ in the unmarked/marked dichotomy and cannot, therefore, go unnoticed; an attempt needs to be made to reconstruct the translator’s decision-making process. In the following example: (15) a. انها حبيبتي... حبيبتي التي ال توصف،…وهناك سلوى حبيبتي الوحيدة. أال يكفي ذلك لكي تعرف سلوى؟.. حبيبتي أنا b. … and there’s Salwa, my one and only beloved, my marvelous, indescribable beloved. She’s my sweetheart, my sweetheart. Isn’t it enough for Salwa to be my sweetheart for you to know who she is? The word ‘ حبيبتيbeloved, sweetheart’ is used 4 times in the ALC. In the translation, however, there are 5 occurrences synonymous to this lexical item. Although the translator has rendered the Arabic item by 25 two different lexical synonyms, she has nevertheless added one more repetition to the corresponding translation counterpart in the TT. Two relevant observations can be made about the ST-TT text-portions above. First, the ST has an LC of 4 lexical words whereas the TT translation counterpart contains 2 occurrences of the word ‘beloved’ and 3 of ‘sweetheart’. In other words, and as a result of the translator’s use of a second shift which has led to the use of two different lexical synonyms to the ST’s حبيبتي, no one single LC in the TT is actually longer than that of the TT. The second observation is that the extra repetition of ‘sweetheart’ comes as part of an added phrase, viz. ‘for Salwa to be my sweetheart’. This whole TT phrase, it can be noticed, is the translation counterpart of the ST’s deictic word ‘ ذلكthat’. In other words, the extra repetition shift has come as a by-product of the translator’s attempt to explicate the reference of the deixis in the ST. A shift like this, it is to be pointed out once more, is bound to increase the explicitness level in the TT, as was mentioned earlier in the Introduction in relation with the Explicitation Hypothesis and as will further be discussed later in Section 4. Another example of this type of extra-repetition shift can also be found in the following ST-TT text portions: (16) a. . وفي ذيل الذاكرة صورة من بقايا كوابيس تدور حول أشخاص يريدون قتلي،... ... …وأن ثمة صورة قديمة. b. … and the back of my mind was haunted by nightmares’ lingering images - - images of people wanting to murder me, . . . and that in one of his pictures, . . . 26 Notice again that the translator has performed two types of shifts in the TT-portion above: (1) the extra-repetition shift, by adding the second occurrence ‘images’, and (2) the synonymy shift, by rendering the ST’s صورةinto two different lexical synonyms: ‘image’ and ‘picture’. The extra use of ‘images’ above seems to have been motivated by the significant textual function that the repetition texteme of the lexical word صورةplays in the ST. This functional value seems to result from the protagonist’s highly-confused psychological world, as depicted in the story; a world full of imaginary ‘pictures’ and ‘images’. The repetition of ‘images’ above also seems to embellish the above text and add to its rhetorical force. 3.8. Shifting by Substitute Words Another type of shift found to be operative is that of using a substitute word in the TT to stand for a repeated word in an ST lexical chain. This translation strategy would serve two ends: (1) It cuts down the level of explicit lexical repetition; and (2) It preserves the cohesive function of lexical reiteration. Examples of the use of both verbal and nominal substitute words have been detected in the corpus.5 Three of such examples are reproduced and briefly discussed below. (17) a. لو كنت أعرف، لو كنت أعرف لما كنت حزينا ً الى هذا الحد،أنا ال أعرف .كنت أعدت المسألة الى عواملها األولية b. I don’t know. If I did, I wouldn’t be in such distress. If I knew, I would have reduced the problem to its basic elements. See Halliday and Hasan: 92, for more details on the cohesive role of ‘substitution’ in text and types of substitute words. 5 27 Text cohesiveness in the above TT lexical chains is still maintained through substituting كنت أعرفby ‘did’, although the lexical repetition of ‘knew’ is not retained. (18) a. أو بكلمات كتلك التي يتحدث بها المعلمون والطلبة الكبار،…يخاطبني بهدوء …ولم أكن أفهم كل الكلمات التي كان ينطق بها b. …but address me in a calm tone of voice, and with the kind of words that teachers use with students who are older … I didn’t understand all the things he used to say … In this case, the general word ‘things’ is used in the text fragment above to stand for ‘ الكلماتwords’ in the ST. This is another common means of the substitution shift, which the translator has utilized. (19) a. انه فيما أظن ال يتسع،انه مقهى صغير وهو ال يتسع لكثير من الموائد فالمقهى صغير... …اال لمائدتين. b. It’s a small coffee shop and it isn’t big enough to accommodate many tables. If I’m not mistaken, there’s only room for two tables … After all, it’s a tiny place. Another general word yet, viz. ‘place’, is used by the translator as a substitute word to replace ‘coffee shop’ in the above TT text-portion. In all the three examples above, the translator has managed to lessen the level of lexical repetition in the TT. This, as mentioned earlier, 28 goes in line with the dominant trend that translated texts in general tend to exhibit. This substitution shift does not seem, however, to seriously impair the textual function of repetition since the replaced items are still easily retrievable. Neither is the textual cohesiveness compromised by this shift of substitution; as can be seen from the above discussion.. 3.9. Nominalization Shifts In this type of shift, a personal pronoun in the ST is replaced by the proper noun of its referent. Only one instance of this type of shift has been detected in the study corpus. It is useful to keep in mind that this type of shift is just the opposite of that of the pronominalization shift, discussed earlier in 3.6. The single available example found in the study corpus is reproduced below, followed by a brief discussion: (20) a. . وكنت أكره الرياضيات وأحبه هو... يقفز الى رأسي إسم األستاذ شريف b. Then suddenly there leaps to my mind the name of Mr. Sharif … I used to hate math, yet I loved Mr. Sharif. In the TT above, the translator has added yet another lexical repetition to the already long lexical chain found in the full version of the ST. She has replaced the ST’s personal pronoun ‘ هوhe’ by ‘Mr. Sharif’ in the TT, although this particular case cannot be taken to be motivated by a process of disambiguation. However, and despite its rarity in the corpus of the present study, such translation shift is not uncommon though and goes in line with the Explicitation Hypothesis. In a study of lexical cohesion in the translated novel The Thief and the Dogs of Naguib Mahfouz, Abdel-Hafiz points out that the “presence of 29 ambiguous referents in the ST can motivate translators to shift from pronouns to common/proper nouns in the TT”. He then gives the following, among many others, as an example of this explication translation strategy: (21) a. وانتزع عينيه من الجريدة فرأى الشيخ علي الجنيدي ينظر الى السماء . ولسبب ما أخافته ابتسامته.من خالل الكوة ويبتسم b. He tore his eyes from the paper and found the Sheikh staring through the window at the sky, smiling. The smile for some reason or other, frightened Said. The translator’s decision to replace the underlined Arabic pronominal above by its explicit proper noun in English seems to be motivated by the desire to ward off any possible ambiguity due to the presence of more than one antecedent in the ST. Such translation shift, albeit uncommon in our data, also points to the incoherence of translators’ decisions in general, and those regarding translation shifts of lexical repetition, in particular, since the general tendency is to reduce rather than expand the repetition, as shown earlier. I am not postulating, however, that such discrepancy in translation strategies is totally unmotivated. In fact, as was just pointed out above, translators usually have their textual and/or cultural motives. Thus, efficient translators may be tempted to execute seemingly ‘aberrant’ translation shifts. In doing so, they may themselves belong to certain societal subgroups or are exposed to a fledgling set of norms that seem to lurk in the periphery of mainstream norms or lie in the centre of subsystem ones. Such norms may be considered centrifugal in their directionality according to today’s 30 prevailing standards, but they do exist and they do leave their unmistakable traces both on the translation process and the translation product, no matter how limited or nebulous. This multiplicity of norms should not, however, be mistaken for the absence of norms or for anarchy. The translator’s ability to manoeuvre between alternative modes of behavior is, as Toury puts it, “just another norm-governed activity, necessarily involving risks of its own” (in Schäffner ed., 1999: 27). This issue, however, will be taken up again in Section 4 below. 4. Discussion After having surveyed the different types of shifts detected in the translated text, it is now imperative to try to speculate on what lies behind them. The question being asked, therefore, is what could have motivated the translator to decide to perform these in the TT? Translated texts are known to exhibit tension between two poles: that of ‘adequacy’ in relation to the ST, on the one hand, and the pole of ‘acceptability’ by the TL and its culture, on the other; each with its characteristic text norms. Thus, every translated text lies somewhere between these two extremes and the translator’s decision-making process is, consciously or subconsciously, influenced by the pressures exercised on him/her by these two poles. The following discussion is, hence, an attempt to understand the effects of the above-mentioned tension on the translator’s decisions with respect to the different types of shifts listed and discussed in Section 3. As was already mentioned in the Introduction, lexical repetition is a textual phenomenon found in both Arabic and English, as well as in other languages. Rhetorical norms in Arabic are, however, known to allow texts to exhibit a higher degree of this phenomenon than in English. In English rhetoric, as was mentioned in the Introduction, lexical repetition is tolerated and made use of as a figure of speech; its use must still be motivated though. Contrariwise, lexical repetition in 31 Arabic does not have to be used as a figure of speech that requires justification, but is rather regarded as the default state of affairs. Keeping this distinction between Arabic and English in mind would help us understand and explain most the above-mentioned shifts found in the translated text. A bird’s eye view at the different types of shifts surveyed in the previous section of the paper would reveal that they actually fall into three major categories of shifts, as far as lexical repetition is concerned. These are: (a) Avoiding/minimizing lexical repetition; (b) Retaining it, but with some modification/alteration; (c) Emphasizing it by extension/expansion The following discussion of each of the three groups of the translation shifts stated above aims at discovering and interpreting the translator’s motives which lie behind opting for one or the other of these shiftgroups. 4.1. Avoidance of Lexical Repetition In general, one of the most important of any translator’s tasks is to reformulate the ST in a way that makes it ‘acceptable’ to the textual standards and expectations of the target language and its culture. In our case, this would mean cutting down on the frequent occurrences of lexical repetition from Arabic texts translated into English since the translator is expected to be aware of the textual norms of both the ST and TT. Consequently, the translator’s attempt to produce a text which would identify with and abide by the textual norms of the TT/TL can help explain instances in the translated text where lexical repetition has been purposefully avoided by one means or another. 32 The first category of shifts above, viz. that of avoiding one or more instances of repetition in a ALC, has been found to be the most common type of shift utilized by the translator. In her attempt to adapt the translated text to the textual norms of English, the translator has basically worked towards minimizing lexical repetition by opting not to repeat one or more certain lexical item(s) within an ALC. To perform the decision as a translational ‘solution’ for such ST ‘problem’, the translator has adopted a number of strategies. By referring to Section 3, one can find out that this policy of deliberate avoidance has been actually implemented by one or more of the following translation strategies, in the order of their frequency of occurrence: 4.1.1. Replacement of instance(s) of lexical repetition in the translated text by (i) a synonym different from others, as in Shift 3.1.; or by (ii) a paraphrase of the replaced lexical item, as in Shift 3.3. This policy of using lexical/phrasal synonymy has been used to minimize lexical repetition in 49 instances out of the total number of shifts in the analyzed TT, which is 98. This repetition-avoidance policy thus represents 50% of all the shifts detected in the translated text. 4.1.2. Replacement by zero, viz. deleting one lexical repetition or more in a ST text-portion from its translation counterpart in the TT, as in Shift 3.2. A percentage of 19% of such shift has been found in the corpus. 4.1.3. Replacement of a repeated word by a personal pronoun or a substitute word. Nine such instances, i.e. 9%, have been detected, as in shifts 3.6 and 3.8. 33 Reducing the density of lexical repetition in the TT through the above different means of replacement counts for more than 75% of all the translation shifts performed in the translated text. As I argued above, the abundance of this translation policy of avoiding lexical repetition reflects the translator’s incessant attempts to approximate the textual norms of English, which stipulate that lexical repetition must be rhetorically motivated so as to be tolerated. In her attempt to produce an acceptable translation, the translator has thus abided by the standard norms of textuality in English. However, the above discussion may seem to run counter to the findings of many contrastive analyses of original texts in Arabic and English which have discovered that the phenomenon of lexical repetition as a text cohesive device is no less frequent in English texts than in Arabic (see, Fareh 1988 and al-Khafaji 2004; among others). Even simple lexical repetition, viz. repeating the same word with no or minimum formal change, has been found to be similarly frequent in general in the lexical chains of texts in the two languages. Yet, and despite this similarity in the overall frequency of lexical repetition, it has also been found out that there exist some significant differences between the LCs in the two languages, as far as the distribution of this linguistic phenomenon (see, al-Khafaji 2004). The most important of these are that: (a) Arabic tends to have longer6 LCs in its texts; and (b) Long LCs in Arabic exhibit a significantly much higher frequency of simple lexical repetition, i.e. with no or very little formal variations,than long LCs in English texts. The above findings point to some distinctive norms of textuality in the two languages. Can these distinctions explain the translator’s decision6 The length of an LC is counted by the number of those lexical words which enter into the relationship of lexical repetition and thus make up that LC. 34 making process of avoiding excessive lexical repetition by replacement, as demonstrated and discussed above? To test the tenability of the above hypothesis, the length of ‘long’ LCs in the ST needs to be examined and measured. Before proceeding to do so, however, it must be pointed out that the distinction between ‘long’ and ‘short’ LCs is a relative question and that there is no absolute cutting-point between the two; viz., a long LC in one text may be considered relatively short in another and vice versa. It all depends on counting the average length of all LCs in a given text; LCs above the average are then considered as being longer than those below it. Based on this criterion, the average length was consequently counted for all lexical chains found in the analyzed Arabic text. 7 This was found to be almost 4.9 words. However, when the average length was calculated just for those ALCs in which the translator has chosen to replace their repetition(s) in the TT by shifts of synonymy, paraphrase, or deletion, it was found to be 5.5 words. It thus becomes safe to postulate that the overwhelming majority, if not all, of the TT’s lexical chains in which the avoidance-by-replacement translation policy was exercised are translation counterparts of long LCs in the source text. In light of this, the translator’s decision against retaining lexical repetition of one or more instances of the translation counterparts of such ST lexical chains can be understood to have been well-motivated since it is in such long LCs that English texts exhibit different distributional norms, as was argued above. The translator’s decision to render the replaced LC constituents by synonymy or paraphrase, as was shown above, can also be understood on the grounds that these textual cohesive devices of lexical reiteration have been found to be the most frequent next to lexical repetition in English texts (Fareh 1988). So, in text portions where the high level of lexical repetition becomes intolerable, according to the textual norms of English, Arabic-English translators are expected both to reduce the 7 Only LCs which comprise 3 repeated words or more were actually taken into consideration since 2-word LCs are disregarded for being too frequent in text to be of much significance. 35 level, as well as to do so by resorting to the alternative means of synonymy, paraphrase or deletion. 4.2. Retention with alteration(s) A limited number of shifts was found to lie somewhere between the two ends of the TT-pole and the ST-pole. In such shifts, the translator has neither wholly retained lexical repetition nor has she replaced it. Instead, she has chosen to retain the nucleus of the repeated word but added inflectional and/or derivational morphemes to it so as to introduce variation into lexical repetition, as in Shift 3.4. Or, alternatively, she has retained the repetition but within a newlyintroduced word group, as in Shift 3.5. Together, the instances of these two shifts in the corpus make up to 15%. A translated text in general is subject as an inter-text to ambivalent pressures from two poles: the TT’s and the ST’s. As a result, the translator’s decisions and the norms s/he abides by may sometimes oscillate between the two opposing ends of acceptability and adequacy, though the norms of the former usually seem to have the upper hand. Shifts may thus, in principle, occur in either direction (cf. Toury 1980:59). The aim to simplify and explicate some information in the ST text to the TT readership may thus justify to the translator the modified retention of lexical repetition, as is the case with performing Shift 3.5. As was also already pointed out, the phenomenon of increased simplification and explicitness has in fact been observed to be a common characteristic of translated texts in general, according to the Explicitation Hypothesis. In the same vein, variations introduced on the form of repeated words, as is realized by Shift 3.4, seem to help the translator alleviate lexical repetition and render it more acceptable to the norms of English. 36 4.3. Addition of repetition(s) A few instances, about 10%, have also been detected in the translated text where the translator has, rather unexpectedly, opted for a set of norms which seemingly runs counter to what has been practiced so far. In such cases, the translator has not only retained and announced ST repetition but has actually added to it and extended it in the TT, as performed by Shift 3.7 as well as Shift 3.9. This phenomenon can be understood in light of the moving scale of the norm-system which translators seem to apply at different junctures during the formation and reformulation of the TT. One feels especially justified in postulating this argument since no linguistic rules of English could have made the lexical addition obligatory, or even preferable, in these cases.8 Other normative considerations, however, must have motivated the translator not to heed to the general rules of the acceptability norms in this case. Yet although on the face of it the adequacy norms of favoring abundant and frequent lexical repetition in Arabic appear to be the driving force behind the above two shifts, the fact of the matter remains that such shifts have also actually been implemented under pressure from the textual and cultural requirements of the TL. In both Shift 3.7 and Shift 3.9, it is to be remembered, the objective of lexical addition was to explicate some implicit information in the ST text for the benefit of the TT readership. In both shifts, therefore, it is the textual and cultural considerations of the target language which were at play; somewhat from behind the scene, however. I mean, for example, such rules in Arabic which favour adding an ’absolute object’ derived from the same finite verb when rendering into Arabic such sentence in English as ‘They hit him hard, by ( ضربوه ضربا مبرحاThey hit him a hard hitting). 8 37 5. Conclusion and suggestion 5.1. It can be concluded from all the above that in any translation process, the translator is exposed to different, sometimes contradictory, forces which compete with each other. In the case of handling lexical repetition within the context of Arabic-English translation, we have seen two seemingly opposing sets of norms at work: (a) a powerful set, realized by a variety of translation shifts, whose objective is to avoid and cut down ST instances of frequent lexical repetition in the retextualization process of the TT; and (b) a less dominant set of norms which motivates the translator to retain, and sometimes even extend, ST’s lexical repetitions. In between these two sets of polar norms, we have also detected a number of reconciliatory measures. Despite the apparent ambivalence of translation norms, the above discussion has revealed, however, that this contradiction is more superficial than real. Textual and cultural norms of the target language and culture seem to play the decisive role in the operation of all types of translation shifts detected and discussed in the present paper. In fact, it seems safe to conclude thus that it is ‘acceptability’ norms which have been actively instrumental in selecting TT translation ‘solutions’ for the ‘problems’ in the ST, as far as the shifts in lexical repetition are concerned. 5.2. It has been concluded above that acceptability norms are almost exclusively behind the types and frequency of the translations shifts of lexical repetition detected and analyzed in the analyzed text of the present paper. Is this the default situation in all translated texts? Or, is this conclusion –partly at least- attributable to the direction of the translation process being from an ‘underprivileged’ language into a ‘privileged’ one? In other words, are the shifts the result of the 38 ‘hegemony’ that English and its norms impose on languages like Arabic? These are moot questions that await further empirical research. To ascertain that avoidance of lexical repetition, for example, is a tentative translation ‘universal’, as claimed by many translation scholars, translated texts both into and from various languages need to be examined and the results of the analyzed texts be compared. 5.3. Since contrastive Arabic-English research within the framework of Descriptive Translation Studies is still rather scarce, it would be illuminating if the central role which norms and shifts play in translation is further pursued by different, yet complementary, studies like the following: 5.3.1. A comparison of translated and original texts, both within Arabic, can yield much needed information about acceptability norms in Arabic translated texts. Besides, such studies can shed light on some interesting hidden features of the original Arabic texts themselves; which may have evolved as a result of translations into Arabic, especially those from ‘prestigious’ languages like English. 5.3.2. The relationship between translation norms and text-types is another issue worthy of further research. In translating distinguished literary works, as well as canonized texts in general, norms of the original ST are expected, due to their high prestige in the source culture, to exercise more pressure on the translator than in semi- or non-canonized texts. Hence, it would be revealing to study the effects which changing the type of text has on translation shifts and norms. 39 5.3.3. As norms represent socially-determined phenomena, they are bound to be ‘historical’, rather than a-historical, in nature. It would be worthwhile, hence, to find out how norms change over time. It would be highly informative, for example, to investigate some specific translation phenomena such as shifts in lexical repetition in texts translated into Arabic from English at different points of time. References Abdel-Hafiz, Ahmed-Sokarno. 2004. “Lexical Cohesion in the Translated Novels of Naguib Mahfouz: the Evidence from The Thief and the Dogs.” http://www.arabicwata.org Baker, Mona. 1992. In Other Words: A Coursebook on Translation. London and New York: Routledge. xii +304 pp. Ben-Ari, Nitsa. 1998. “The Ambivalent Case of Repetitions in Literary Translation. Avoiding Repetitions: A ‘Universal’ of Translation.” Meta, XLIII, 1, 1-11. Blum-Kulka, Shoshana. 2000. “Shifts of Cohesion and Coherence in Translation.” In Lawrence Venuti (ed.) The Translation Studies Reader. London: Routledge. 298- 329.[xiv + 524 pp.] Catford, J. C. 2000. “Translation Shifts.” In Lawrence Venuti (ed.) The Translation Studies Reader. London: Routledge. 141-147. Fareh, Shehdeh I. 1988. Paragraph Structure in Arabic and English Expository Discourse. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Kansas. ix + 312 pp. 40 Halliday, M.A.K. and Ruqaiya Hasan. 1992. Cohesion in English. London and New York: Longman. xv + 374 pp. Hatim, Basil and Ian Mason. 1997. The Translator as Communicator. London: Routledge. xii + 244pp. Johnstone, Barbara. 1991. Repetition in Arabic Discourse. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. 130pp. al-Khafaji, Rasoul. 2005. ”Variation and Recurrence in the Lexical Chains of Arabic and English.” Poznan Studies in Contemporary Linguistics (PSiCL), 40, 5-25 Lotfipour-Saedi, K. 1997. “Lexical Cohesion and Translation Equivalence.” Meta, XLII, 1, 185-192. Schäffner, Christina. 1999. (ed.) Translation and Norms. Clevedon/Philadelphia: Multi- lingual Matters Ltd. 140 pp. Toury, Gideon. 1995. Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.viii + 311 pp. Toury, Gideon. 1980. In Search of a Theory of Translation. Jerusalem: Academic Press. 159 pp. Venuti, Lawrence. 2000. (ed.) The Translation Studies Reader. London/New York: Routledge. xiv + 524 pp. Vinay, Jean-Paul and Jean Darbelnet. 1995. Comparative Stylistics of French and English: A Methodology for Translation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. xx + 358 pp.