Measuring Employee Engagement in the

Australian Public Service

Tony Cotton

December 2012

1

Measuring Employee Engagement in the

Australian Public Service

Tony Cotton

December 2012

2

Contact and Acknowledgement Information

Enquiries about Australian Public Service Commission Staff Research Insights

are welcome and should be directed to:

Humancapitalmatters@apsc.gov.au

Electronic copies are available at: http://www.apsc.gov.au

© Commonwealth of Australia 2012

All material produced by the Australian Public Service Commission (the

Commission) constitutes Commonwealth copyright administered by the

Commission. The Commission reserves the right to set out the terms and

conditions for the use of such material.

Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, and those

explicitly granted below, all other rights are reserved.

Unless otherwise noted, all material in this publication, except the

Commission logo or badge, the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and any

material protected by a trade mark, is licensed under a Creative Commons BY

SA Attribution Share Alike 3.0 Australia licence. Details of the licence are

available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/au/legalcode.

Attributing Commission works

Use of Commission material licensed under a Creative Commons BY SA Attribution

Share Alike 3.0 Australia licence requires you to attribute the work in the manner

specified by the Commission (but not in any way that suggests that the

Commission endorses you or your use of the work). It is important to:

-- provide a reference to the publication and, where practical, the relevant

pages

-- make clear whether or not you have changed Commission content

-- make clear what permission you are relying on, by including a reference

to this page or to a human-readable summary of the Creative Commons BY SA

Attribution Share Alike 3.0 Australia licence

-- do not suggest that the Commission endorses you or your use of our

content.

For example, if you have not changed Commission content in any way, you

might state: “Sourced from the Australian Public Service Commission

publication [name of publication]. This material is licensed for reuse under a

Creative Commons BY SA Attribution Share Alike 3.0 Australia licence.”

If you have made changes to Commission content, it would be more

accurate to describe it as “based on Australian Public Service Commission

content” instead of “sourced from the Australian Public Service Commission”.

An appropriate citation for this paper is:

Cotton A.J. 2012, Measuring Employee Engagement in the Australian Public

Service, Australian Public Service Commission Staff Research Insights,

Canberra.

Enquiries

For enquiries concerning reproduction and rights in Commission products

and services, please contact communicationsunit@apsc.gov.au

3

MEASURING EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT IN THE

AUSTRALIAN PUBLIC SERVICE1

An Overview of Employee Engagement

The concept of employee engagement is widely used in the human resources literature.2 While

the exact origin of the concept is difficult to determine, it is often considered to have evolved

from the concepts of job satisfaction, organisational commitment, and organisational

citizenship behaviour. Multiple definitions of employee engagement have emerged in the

literature which presents particular challenges for both managers and human resource (HR)

practitioners:

For an HR executive, getting a handle on employee engagement can be like trying to

catch a greased pig at a country fair. Just when you think you've got it, it slides right

out of your hands. 3

One of the contributors to this confusion is the fact that the concept of engagement developed

initially from organisational practice rather than from academic research and many of the

authors in the field lack a degree of independence in their writing because they are in the

business of delivering employee engagement solutions to organisations.4 As a result, there has

tended to be limited collaboration or information sharing on the concept as many of the authors

are, in fact, competitors genuinely seeking to protect their intellectual property.

While this pattern of development from practice to academia may not have been conducive to

developing a unified understanding of the concept of engagement, it is not unique. The concept

of burnout, for example, was well developed in the practitioner literature before being

embraced by academia. Similarly the initial writing on emotional intelligence was almost

entirely in the practitioner sphere.

Despite this lack of cohesion in the literature there are some general conclusions that can be

drawn about the concept of employee engagement:

It is a much broader concept than either that of ‘commitment’ or ‘motivation’ that one finds

in the academic or practitioner literature.

The considerable amount of research and analysis that has been conducted on engagement in

the last 10 years suggests that it is more than a passing management fad.

1

Australian Public Service Employee Engagement Model by Australian Public Service Commission is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

2

Scottish Executive Social Research Employee Engagement in the Public Sector: A Review of the Literature.

Edinburgh, May 2007. This is a very comprehensive review of the literature in this area and is the source of much of

this section of this paper.

3

Terms of Engagement Scott Flander (2008), http://www.hreonline.com/HRE/story.jsp?storyId=59866490.

4

Scottish Executive Social Research. Employee Engagement in the Public Sector: A Review of the Literature.

Edinburgh,, May(2007), p 3.

4

The quality of the thinking and measurement methods has improved significantly in the last

10 years.

Also, there are a number of features of employee engagement have been consistently identified

in the literature5:

Employee engagement is generally seen as a two-way interaction between the employee and

the organisation.

There are many characteristics of an ‘engaged’ employee including: commitment, pride and

advocacy of the organisation, a connection with the organisation’s strategy, and a stated

preparedness for discretionary effort in the workplace.

While the literature has identified many ‘drivers’ of engagement, differences exist across

different organisations and even among different elements of the same organisation and, as a

result, there is no ‘template’ solution for engagement.

Although there have been considerable claims made about the positive benefits of increasing

employee engagement on tangible organisational outcomes, these tend to be based on

correlation or co-incident results rather than any research demonstrating causality.

Approaches to Measuring Employee Engagement

There are many “models” of employee engagement in the literature and they tend to fall into

two broad categories. The first is often found in the practitioner literature and conceptualises

engagement as a single, omnibus construct that can be measured as such. These models often

are associated with a particular provider, commonly use self-report attitudes such as loyalty and

advocacy as indicators of engagement and often cite the pursuit of engaged employees as an

end in itself. Advocates of these models will often refer to a global relationship between the

number of engaged employees and organisational performance but without any examination of

the elements or nature of this relationship. One of the most widely known examples of this type

is the Gallup Q12.6

The second type of employee engagement model is more common in the academic literature

and argues that engagement is a multi-dimensional concept and more comprehensively

examines the links between the antecedents7 of engagement and the consequences8 of

engagement. A good example of this type of model is provided by Saks.9

Much of the practitioner literature on employee engagement takes a highly data-driven

approach with often-limited formal theoretical consideration of nature of the link between

5

Scottish Executive Social Research. Employee Engagement in the Public Sector: A Review of the Literature.

Edinburgh,, May(2007).

First, break all the rules: what the world’s greatest managers do differently. Buckingham, B., and Coffman, C.,

1999.

6

7

Those characteristics of the workplace and the workforce that are required for engagement to occur, they are often

referred to as “drivers” of engagement.

8

The attitudes and behaviours exhibited by “engaged” employees.

9

Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21 (7),

(2006).

5

employee engagement, employee behaviour, and subsequent work performance. The Gallup

Q12 model is a good example of the use of rigorous statistical methods on a vast amount of

data to identify a set of survey questions that:10

... link powerfully to key business outcomes. These 12 statements emerged as those that best

predict employee and workgroup performance.

And while the empirical rigour behind such models is not in question, this data-driven approach

can lead, at times, to a lack of understanding, or even critical examination, of the theoretical

foundations underpinning the concept of employee engagement. As one author concludes:

‘...the relationships among potential antecedents and consequences of engagement as well as

the components of engagement have not been rigorously conceptualized, much less studied.’11

And without any understanding of the relationship between the antecedents and consequences

of employee engagement it is impossible to understand how this relationship might influence

organisational outcomes.

Many published models fail even to attempt to identify a link between engagement and actual

organisational outcomes but focus instead on self-report attitudes or opinions as the “outcome”

of engagement. One very well regarded model, in a manner that is not uncommon, cites being

engaged, being positive about customer focus, and being positive about organisational values as

valid organisational outcomes of employee engagement.12 All of which are important attitudes

for employees to possess but the model fails to provide any clear link between these attitudes

and actual behaviours that result in organisational outcomes. Moreover, while many authors

claim evidence that organisations with high engagement have better organisational performance

than organisations with lower engagement scores, they offer no explanation of why this might

be occurring.

The evidence used to support many of the assertions made about employee engagement in the

practitioner literature in particular, does not allow examination of the nature of the relationship

between engagement and its outcomes. Yet many authors speak about engagement with

impressive hyperbole, for example ‘…engagement remains the ultimate prize for

employers…’13

Engaged and Disengaged Employees

Another element common among many models of employee engagement is that they segment

the workforce into ‘engaged’ and ‘disengaged’ staff. This is consistent with the idea that

engagement is a unidimensional concept and that there is some absolute benchmark against

which one can identify an engaged, or disengaged, employee. Many authors speak about

‘disengaged’ staff in highly emotive language:

10

http://www.gallup.com/consulting/52/employee-engagement.aspx

11

Macey, W.H., and Schneider, B. The Meaning of Employee Engagement. Industrial and Organizational

Psychology, 1, 2008, p 4.

12

Employee Engagement underpins Business Transformation. Towers Perrin, 2009.

http://www.towersperrin.com/tp/getwebcachedoc?country=gbr&webc=GBR/2008/200807/TP_ISR_July08.pdf

13

Working Today: Understanding what drives employee engagement. Towers Perrin, 2003.

http://www.towersperrin.com/tp/getwebcachedoc?webc=hrs/usa/2003/200309/talent_2003.pdf

6

…disengaged employees erode an organization's bottom line while breaking the spirits of

colleagues in the process. 14

The combination of such extravagant claims in the absence of an agreed definition of employee

engagement, or a more complete understanding of the nature of engagement with clear links to

organisational outcomes, has contributed to a degree of confusion and a subsequent loss of

confidence by managers in the concept of engagement. It has been noted that:

…senior HR leaders and their colleagues in the executive suite have grown increasingly frustrated,

questioning the concept of employee engagement itself, as well as the ultimate return from

investments made to drive the engagement of their workforces. 15

The failure to establish a common definition of the concept of engagement with a clear link

between the antecedents and consequences of engagement is a deficiency of many of the extant

models of employee engagement. Without a clear understanding of the nature of employee

engagement it is impossible to measure which:

... is a matter of particular significance to those who develop and conduct employee surveys in

organizations because the end users of these products expect interpretations of the results to be

cast in terms of actionable implications. Yet, if one does not know what one is measuring, the

action implications will be, at best, vague and, at worst, a leap of faith. 16

And it is this point that is particularly germane when considering the concept of employee

engagement in the APS.

The APS Context for Employee Engagement

Any consideration of employee engagement in the APS must recognise the organisations

business context. The APS is a complex organisation with over 160,000 employees, working in

more than 100 organisations that range in size from less than 10 to almost 40,000 employees.

The nature of work done in agencies varies substantially though can be classified into four

broad functional types: policy, operations, specialist, and regulatory each of which has different

workplace characteristics.

As well as this diversity, there are a number of enduring features of the public sector that are

also common across the APS and that serve to separate it from the private sector. The concept

of public service motivation17 has an entire academic literature devoted to it for example.

Understanding that there are difference between the public and private sectors is important

because most of the engagement research is conducted in the private sector, and has led some to

14

http://www.gallup.com/consulting/52/employee-engagement.aspx

15

Corporate Leadership Council, Driving Employee Performance and Retention through Engagement. Corporate

Executive Board, Washington, D.C. 2004.

16

Macey, W.H., and Schneider, B. The Meaning of Employee Engagement. Industrial and Organizational

Psychology, 1, 2008, p 4.

17

Perry, J.L., Hondeghem, A., and Wise, L.R. Revisiting the Motivational Bases of Public Service: Twenty Years of

Research and an Agenda for the Future. Public Administration Review, 70 (5), p 681-690.

7

conclude that there is little difference in employee engagement across the two sectors18, which

seems presumptuous given the lack of engagement research done in the public sector.

Employee Engagement as an Element of Human Capital

One key driver in rethinking employee engagement in the APS has been the adoption of the

concept of human capital as a fundamental way of thinking about APS workforce capability.

Ahead of the Game: Blueprint for the Reform of Australian Government Administration19 (the

APS Reform Blueprint) quite deliberately introduced the term human capital to drive a shift in

APS thinking to a more strategic and forward looking approach to workforce capability.

A fundamental principle of a human capital approach is that the workforce is an important

contributor to organisational capability and, as a result, employee engagement in the APS is

meaningful only if it can be related to the workforce’s contribution to organisational outputs

and outcomes. This is echoed in some of the more recent engagement literature; for example,

Ellis and Sorenson20 state that employee engagement should ‘...always be defined and assessed

in the context of productivity’. Key to this is whether it is possible to develop an explainable

and measureable model of employee engagement in terms of the relationship between its

antecedents and consequences in the APS context.

Understanding Engagement in the APS

The starting point for developing an explainable and measureable model of engagement in the

APS is the generally held view that engagement is a two-way, reciprocal, relationship between

the employee and the workplace.

As a concept, employee engagement represents an evolution in thinking about people and work

from concepts such as job satisfaction. Omnibus measures of job satisfaction have been shown

to be substantially influenced by the personality of the employee so that “...organizational

efforts to improve long-term job satisfaction in employees are probably futile.” 21 Moreover, the

relationship with job performance has been shown to be so low that efforts to improve

performance through job satisfaction may in fact be counter-productive.22 And, while the

relationship between job satisfaction and organisational withdrawal behaviours such as turnover

is stronger, there are many confounding variables in these relationships.

One key feature of engagement as a concept is the idea that there is a reciprocal nature to the

relationship between the employee and their work. The relationship is based on an exchange

18

Scottish Executive Social Research Employee Engagement in the Public Sector: A Review of the Literature.

Edinburgh, May 2007, p2.

19

Advisory Group on Reform of Australian Government Administration, Ahead of the Game: Blueprint for the

Reform of Australian Government Administration. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra, 2010.

20

Ellis, C.M., and Sorenson, A. Assessing Employee Engagement: The Key to Improving Productivity. Perspectives:

Insights for Today’s Business Leaders, 15(1), January 2007.

21

Muchinsky, P.M. Psychology Applied to Work: an introduction to industrial and organisational psychology. 10th

Edition. Hypergraphic Press, Summerfield NC, 2012. p305.

22

Muchinsky, P.M. Psychology Applied to Work: an introduction to industrial and organisational psychology. 10 th

Edition. Hypergraphic Press, Summerfield NC, 2012. p306.

8

between the employee and their work; the employee gains from their participation in work

(remuneration, prestige, social connectedness, etc.) and reciprocates by understanding and

meeting workplace needs (effort, timeliness, etc.), remaining in the workplace, and applying

effort to their work. The reciprocal nature of the relationship between the employee and their

work is fundamental to employee engagement.

As in any human relationship, trust is a key part of this relationship. An employee will form a

set of expectations about their workplace, when these are met, their trust is justified and this

will have a positive impact on the employee. But when expectations are not met, or there has

been a breach of trust, this can have substantial negative consequences for the employee23.

Trust in the workplace is a prominent feature in the literature related to the psychological

contract24 and workplace bullying25; and it is a key element of the employee engagement

relationship.

A final and important consideration in understanding engagement in the APS it the multidimensional nature of “work” in the modern workplace; the concept of “work” has evolved

substantially from a means of obtaining economic subsistence26 to something much more

complex. In the modern workplace employees are likely to engage with many different aspects

of the workplace and therefore employee engagement is almost certainly a multi-dimensional

concept. A number of authors, particularly in the academic literature have theorised on the

multi-dimensional nature of engagement.27

A Model of APS Employee Engagement

Given this thinking, a number of parameters were identified that needed to be satisfied before a

model of engagement could be considered suitable for the APS; specifically, the model needed

to:

provide clear links between the antecedents (or drivers) of engagement and the

organisational outcomes of engagement; and

reflect the multi-dimensional nature of the modern APS workplace.

An extensive examination of both the practitioner and academic literature identified that the

Corporate Leadership Council (CLC) employee engagement model28 satisfied both of these

parameters.

23

Helliwell, J. and Huang, H. Wellbeing and trust in the workplace. National Bureau of Economic Research

Working Paper 14589. Cambridge, MA.

24

See, for example, Rousseau, D.M., Psychological Contracts in Organisations: Understanding written and

unwritten agreements. 1995. London, Sage.

25

See, for example, Georgakopoulous, A., Wilkin, L, and Kent, B., Workplace bullying: a complex problem in

contemporary organisations. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(3). 2011, pp 1-20.

26

Thomas, K. The Oxford Book of Work. Oxford University Press, 1999, p 23.

27

See, for example: Kahn, W.A. (1990). Psychological Conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at

work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee

engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21 (7), (2006).

28

Corporate Leadership Council, Driving Employee Performance and Retention through Engagement. Corporate

Executive Board, Washington, D.C. 2004.

9

The CLC Model of Employee Engagement

The CLC model is underpinned by a definition of ‘purposeful’ engagement that clearly links

engagement with organisational outcomes:

The Council has defined engagement as the extent to which employees commit—both rationally

and emotionally—to something or someone in their organization, how hard they work, and how

long they stay as a result of that commitment. By using this outcomes-focused definition, we can

measure the tangible benefits of engagement, as opposed to focusing on ‘engagement for

engagement’s sake.

The model is also multi-dimensional being based on the idea that staff commit, in varying

levels, to the following elements of their workplace: their job, their team, their immediate

supervisor, and their organisation.

As well as having a basic conceptual framework, the CLC Engagement Model has a strong

empirical basis having been developed on a large sample of employees surveyed across a

number of private and public organisations.29 It integrates key concepts from the organisational

commitment literature,30 in particular the idea that commitment to the workplace can have both

a rational and emotional component31 and it provides a clear link between organisational

outcomes and engagement including improved employee performance and retention.

The CLC claim three key findings from their research:

Successful engagement strategies begin with an outcome focussed definition of engagement

The majority of employees are neither fully engaged nor fully disengaged

Employee engagement has a significant impact on performance and retention

The outcomes-focussed definition means that the CLC model allows for the examination of the

nature of the relationship between engagement and its consequences rather than simply saying

that a relationship exists. The finding regarding the number of “engaged” or “disengaged”

employees is consistent with a view that there is no absolute point beyond which an employee

is (dis)engaged but rather that employee engagement should be considered in more relative

terms. Finally, the link between employee engagement and important organisational capability

inputs such as performance and retention is entirely consistent with the APS context and a

necessary requirement for any model of APS employee engagement.

The model also allows a more sophisticated examination of the nature of the relationship

between the employee and their work. It includes elements of engagement identified in other

research, (e.g., job and organisational engagement32) as well as adding engagement with two

important elements of the workplace: one’s team and immediate supervisor. Because the model

hypothesises a relationship between each individual element of engagement and specific

29

Over 50,000 employees, from 59 different companies or government organisations in 27 different countries.

30

Organisational commitment is one of the seminal inputs in the development of concept of employee engagement.

31

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human

Resource Management Review, 1, 61–89.

32

Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21 (7),

(2006).

10

organisational performance outcomes (in this case in terms of employee performance and

retention) it allows one to consider the possibility that there is a compensatory characteristic to

engagement where, for example, high levels of job engagement compensate for lower levels of

organisational engagement with a result that two employees both produce similar work

performance.

If this is the case, organisations could develop tailored engagement strategies depending on the

nature of the engagement in their workplace, or even within a specific workgroup. Also, it

might be possible to develop different engagement strategies for different segments of the

workforce, for example, senior employees often have different attitudes towards work than

more junior employees. The multi-dimensional and (possibly) compensatory nature of

engagement in the model allows for a more sophisticated and more useful understanding of the

workforce than does the more typical unidimensional view of engagement.

Overall, the CLC model provides a sound conceptual start point for developing a model of

employee engagement for the APS; it meets the parameters defined for consideration and it

allows for a more sophisticated examination of the nature of the relationship between the

antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. However, given the unique aspects of

the APS business context it is necessary to test the theoretical construct of the model in the APS

context and, where necessary, adapt it to suit the APS.

Developing the APS Employee Engagement Model

The APS has routinely collected a wide range of information from its employees through the

State of the Service Employee Survey (the Survey). The Survey is administered annually to a

sample of APS employees and includes a broad range of items ranging from specific aspects of

the workplace to more broad employee attitudes and opinions.

Given the breadth of the Survey, it was determined that a useful initial approach would be to

identify what aspects of employee engagement were already being measured in the Survey and

whether a model of employee engagement for the APS based on the CLC model could be

developed from the existing APS data.

Examination of the contents of the Survey suggested that there were a number of item sets that

mapped closely to the elements of engagement in the model.33 These were:

Job - Q16 Please rate your level of agreement with the following statements regarding your

current job.

Job – Q26 Please indicate your level of satisfaction with EACH of the following workplace

attributes in your current job

Team – Q18 Please rate your level of agreement with the following statements regarding

your immediate work group

Supervisor – Q19 Please rate your level of agreement with the following statements

regarding your supervisor

33

A full list of items is included in Annex A.

11

Organisation – Q20 Please rate your level of agreement with the following statements

regarding the senior leaders (i.e. the Senior Executive Service [SES]) in your agency

Organisation – Q21 Please rate your level of agreement with the following statements

regarding aspects of your agency’s working environment

Data

Data from the 2010 Survey was used for the analyses. The Survey was administered to a

stratified random sample of 9,083 staff of which 5,607 responded. This data set was split into

an Experimental sample (60% of the sample or 3,427 cases) on which the exploratory analyses

were conducted and a validation sample (the other 40%, or 2,180 cases) on which the final

models were validated.

Analyses

Using the Experimental sample, a classical test theory approach was used to determine the

structure of the existing item sets; principal axis factor analysis (PFA)34 was used to determine

the dimensionality of each item set. Factor extraction was determined using a combination of

scree plot and parallel analysis35 and the resulting factor solutions were rotated to simple

structure by oblique rotation (oblimin). Items loading greater than 0.4 on each factor were

included for consideration in the factor make up and final scales were refined using reliability

analysis to make them as parsimonious as possible while retaining the psychometric properties

of the original scales.

The final scales36 and overall model were validated using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA;

using the confa procedure in Stata/IC 10.1)37 on the validation data set. Goodness of fit of the

final models was assessed using the following fit indices:

34

The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) – acceptable model fit is generally indicated by a CFI value

of 0.90 or greater.38

The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) - acceptable model fit can be

indicated by an RMSEA value of up to 0.10.39

The Root Mean Square Residual (RMSR) – acceptable model fit is typically indicated by an

RMSR less than 0.0840 although some authors suggest that a value less than 0.05 is

preferable.41

All analyses were conducted using Stata 10.1/IC.

35

Ender, B. fapara: command to conduct parallel analysis for factor analysis and principal components analysis.

UCLA: Statistical Consulting Group. http://www.ats.ucla.edu/stat/stata/faq/parallel.htm

36

Scales constructed during these analyses used simple unit-weighted linear composites of item scores.

37Kolenikov,

S. (2009). Confirmatory factor analysis using confa. The Stata Journal, 9(3), pp329-373.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional

criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55.

38

39

Kenny, D.A. Measuring Model Fit. http://davidakenny.net/cm/fit.htm

40

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long

(Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136-162). Newsbury Park, CA: Sage

12

For each final scale a “marker” item was identified; this was the item with the highest item-total

correlation and these were used to develop a “short form” of the item set that could be used to

approximate the full model more efficiently.

Results: First Order Analyses

Item 16: Your Current Job

This is one of the larger item sets in the Survey and had 24 items. Factor analysis indicated a

four-factor solution, however, after rotation only one item loaded on factor four at the cut-off of

0.4. The data was re-analysed as a three-factor solution and rotated to simple structure using an

oblique rotation. Confirmatory factor analysis showed a good fit to the three-factor structure

(CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.06, RMSR = 0.05).

The three factors identified from this analysis were labelled: Job Identification, Job

Recognition, and Discretionary Effort.

Job Identification

This factor reflects the level of identification an employee experiences with their job; the initial

factor had nine items loading greater than 0.4 with very high internal consistency (alpha = 0.91)

indicating redundancy in the item set. Refinement of the scale yielded a four-item scale with

very good internal consistency (alpha = 0.85), and a very good correlation with the original set

of nine items (r = 0.96). The items that comprise the scale42 are:

My job allows me to utilise my skills, knowledge and abilities

My work has become a fundamental part of who I am.

Overall, I am satisfied with my job

My job gives me a feeling of personal accomplishment*

Job Recognition

The second factor extracted reflects the broad level of recognition that an employee receives for

their performance. It initially had six items load on it that showed high internal consistency

(alpha = 0.81) and substantial item redundancy. Refinement of this scale yielded a three-item

scale with improved internal consistency (alpha = 0.86) and good correlation with the original

item set (r = 0.92):

I receive adequate recognition for my work contributions and accomplishments

I receive adequate feedback on my performance to enable me to deliver required results

I am satisfied with the recognition I receive for doing a good job*

41

Steiger, J. H. (1990). Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate

Behavioural Research, 25, 173-180.

42

Marker items are indicated throughout by an asterisk (*)

13

Discretionary Effort

The next factor reflected the self-reported discretionary effort that an employee might exhibit.

There were only three items that loaded onto this scale at greater than 0.4 and three items is

considered the minimum number of items needed to create an adequate scale for measurement

purposes. This scale had unsatisfactory internal consistency (alpha = 0.61) and will not be

considered further. An example of an item loading on this scale:

When needed, I am willing to put in the extra effort to get a job done.

Item 18: Your immediate workgroup

Team Behaviour

The original scale was shorter than the previous with nine items and reflected the workplace

behaviours of other members of their immediate team. Factor analysis confirmed that the item

set was unidimensional and reliability analysis showed very good internal consistency (alpha =

0.88) and substantial item redundancy. Scale refinement yielded a four-item scale with very

good internal consistency (alpha = 0.86), and a strong correlation with the original set of items

(r = 0.92) and a marker variable with a very good correlation with the scale (r = 0.88). The

questions in the final scale were:

The people in my work group cooperate to get the job done

The people in my work group share job knowledge with each other

The people in my work group are honest, open and transparent in their dealings*

The people in my work group treat each other with respect

Confirmatory factor analysis showed reasonable fit to a single factor (CFI = 0.99, RMSEA =

0.11, RMSR = 0.02).

Item 19: Your immediate supervisor

Supervisor Behaviour

Supervisor behaviour is represented by another shorter scale that had only ten items that

describes the behaviour of the employee’s immediate supervisor. Factor analysis confirmed

this set of items was unidimensional. The internal consistency of the scale was extremely high

(alpha = 0.93) suggesting redundancy in the items. Scale refinement yielded a four-item scale

with very good internal consistency (alpha = 0.88), a very good correlation with the original set

of ten items (r = 0.95) and a strong marker variable (r = 0.87). The questions in the final scale

were:

My supervisor demonstrates honesty and integrity.

My supervisor shows concern for the welfare of his/her staff

My supervisor encourages and manages innovation

My supervisor provides effective feedback*

Confirmatory factor analysis conducted on the validation sample showed reasonable fit to the

model (CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.12, RMSR = 0.04).

14

Item 20: SES

Agency Leadership

Agency leadership was a shorter scale with only six items and was also clearly unidimensional

with consistently high factor loadings (0.75-0.85), it reflects the quality and behaviour of the

Agency’s senior leaders. The internal consistency was very high (0.92) and indicative of

substantial item redundancy. Scale refinement yielded a three-item scale with very good

internal consistency (alpha = 0.85), very good correlation with the original item set (r = 0.97)

and a strong marker variable that correlated well with the overall scale (r = 0.89):

In my agency, the leadership is of a high quality

In my agency, communication between senior leaders and other employees is effective*

In my agency, the most senior leaders are sufficiently visible (e.g. can be seen in action.

CFA showed reasonable fit to the model but due to the small number of items the traditional

goodness of fit tests could not be conducted. However, when the internal consistency analysis

was replicated on the validation sample it produced very similar results (alpha = 0.84, marker

variable correlation with total r = 0.89).

Item 21: Agency Working Environment

The Agency Working Environment was a larger item set with 21 items. Factor analysis

indicated three stable factors that were extracted from the data and rotated to simple structure.

Confirmatory factor analysis showed some support for this structure (CFI = 0.92, RMSEA =

0.09, RMSR = 0.05). The three factors in this data set were: development, agency behaviour,

and agency identification.

Development

The first factor extracted related to the developmental opportunities provided in the workplace.

It had five items loading on it and good internal consistency (alpha = 0.82), refinement of this

scale saw one item removed which caused a minimal drop in internal consistency (alpha = 0.81)

but retained a very high correlation with the original scale (r = 0.98) and included a strong

marker variable (r = 0.85):

My agency places a high priority on the learning and development of employee.

My workplace provides realistic performance expectations

My workplace provides increased knowledge and/or experience in the job

My workplace provides access to effective learning and development*

Agency Behaviour

The second factor reflected employee’s perception of the organisational behaviour observed in

the agency. It initially had five items load on it greater than 0.4, respectable internal consistency

(alpha = 0.79) and some item redundancy. Scale refinement removed one item which reduced

the internal consistency a little but it still remains respectable (alpha = 0.76), it has a very good

correlation with the original item set (r = 0.97) and a reasonable marker item (r = 0.79):

15

In general, employees in my agency effectively manage conflicts of interest

In general, employees in my agency appropriately assess risk

Employees in my agency feel they are valued for their contribution*

My agency deals with underperformance effectively

Agency Identification

The final factor reflects the level of identification that the employee experiences with their

organisation. It had three items load on it greater than 0.4. The scale had respectable internal

consistency (alpha = 0.73) and as it only has three items no further refinement was done with

this scale. It had a good marker variable (r = 0.84):

Working at my agency is important to the way that I think of myself as a person

When someone praises the accomplishments of my agency, it feels like a personal compliment

to me*

When I talk about my agency, I usually say “we” rather than “they”

Item 26: Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction was measured by a longer set of items that covered a wide range of factors that

might contribute to satisfaction with one’s job. Factor analysis of this scale yielded a stable

simple structure of two factors: workplace challenges and workplace conditions. Confirmatory

factor analyses on these data showed reasonable fit for this model of the data (CFI = 0.96,

RMSEA = 0.08, RMSR = 0.05)

Workplace Challenges

Workplace challenges factor related to the challenges the workplace provided to the employee

in a positive sense. It had six items load on it, but subsequent scale refinement produced a set of

four items that had good reliability (alpha = 0.86) with a strong marker variable (r = 0.87).

Chance to be innovative

Opportunities to utilise my skills*

Opportunities to develop my skills

Interesting work provided.

Workplace Conditions

The second factor reflected the conditions an employee experienced in their workplace. It

showed reasonable internal consistency (alpha = 0.772) but inadequate fit. However refinement

of the scale removed one item causing a minor decrease in internal consistency (alpha = 0.759)

but improved fit (CFA = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.06, RMSR = 0.02). This scale has only a moderate

marker variable (r = 0.66).

Regular feedback/recognition for effort

Good working relationships

Flexible working arrangements

Good manager*

Results: Higher Order Analyses

Having identified a possible set of factors or constructs that might contribute to a model of

engagement from the existing survey items, the next step in testing how the model fit the APS

16

data was to identify whether there was a structure in the data that was consistent with that in the

model. To determine this, a confirmatory factor analysis of the hypothesised four-factor

structure comprising the ten measures described above was conducted using the Validation data

set.

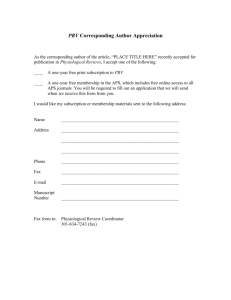

This yielded an acceptable fit of the model to the data (CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.09, RMSR =

0.04) and supported the conceptualised four-factor APS Employee Engagement Model with the

following structure (see also Figure 1):

Job Engagement: Job Identification and Workplace Challenge;

Team Engagement: Team Behaviour and Recognition;

Supervisor Engagement: Supervisor Behaviour and Workplace Conditions; and

Agency Engagement: Agency Leadership, Development, Agency Behaviour, and Agency

Identification.

Figure 1: The APS Employee Engagement Model

Engagement

Components

Engagement

Workplace

Challenge

Job

Drivers of engagement

Team Behaviour

Recognition

Team

Supervisor

Behaviour

Workplace

Conditions

Supervisor

Agency

Leadership

Organisational Performance

Job

Identification

Development

Agency

Behaviour

Agency

Agency

Identification

While the confirmatory factor analysis supports the existence of four separate factors, they are

strongly43 correlated as shown in Table 1.

43

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the behavioural sciences. (2nd Edition). New Your. Psychology

Press.

17

Table 1: Correlations among the elements of engagement.

Engagement

Element

Job

Team

Team

0.6

Supervisor

0.54

0.75

Agency

0.61

0.55

Supervisor

0.5

Using the APS Employee Engagement Model

Understanding Engagement in the APS

The results of the analysis of the Survey have shown that employee engagement in the APS can

be conceptualised as the relationship an employee forms with a number of separate elements of

their work: the job they do, the people with whom they work, their supervisor, and the agency

within which they work.

Job Engagement

In terms of the job people do, engagement is a function of whether the job challenges the

employee; whether it gives them an opportunity to be innovative, gives them an opportunity to

use and develop their skills, and whether it stimulates a degree of interest in the employee. It

also relates to the sense of identification an employee has with the job; do they see the job as a

fundamental part of who they are? Do they get a personal sense of achievement from doing

their job?

Team Engagement

Team engagement revolves around the recognition that employees get for doing their job in a

broad sense: do they receive feedback for what they do, are they happy with the feedback they

get, and does the feedback allow them to do their job better. This is not limited to just feedback

from employees’ supervisors, rather it is open to all forms of feedback. The other component

of team engagement is the work-related behaviour of other team members, does the team share

information, cooperate, and treat each other well; is it a workplace where the employee wants

to come to work?

Supervisor Engagement

The behaviour of immediate supervisors in terms of honesty, concerns for their staff, and the

provision of feedback is a key component of Supervisor Engagement. So too is the workplace

environment and conditions created by the supervisor: the quality of the working relationships,

the flexibility of the working conditions, and the feedback provided to staff.

Agency Engagement

Agency engagement is the most complex component of engagement encompassing the quality

and behaviour of senior leaders, the developmental opportunities provided by the agency, the

behaviours exhibited by agency employees and how well the employee identifies with the

agency, including how well the individual identifies with praise for the agency.

18

A compensatory model

These results show that the elements of engagement are separate but related (Table 1). There is

a degree of correlation among the elements that means that they can be aggregated in a

meaningful way if needed, but that they can also be considered independently, and so can

compensate for each other to some degree in contributing to organisational performance. For

example, high team engagement may compensate for poor job engagement. The compensatory

nature of the model can apply to individuals, workplaces or even agencies. For example a

workplace where work is not particularly challenging for employees might still experience

good organisational performance due to good agency leadership and hence high levels of

agency engagement.

The possible compensatory nature to employee engagement in the APS requires further

examination, but it has the potential to provide managers and HR practitioners a much more

sophisticated understanding of engagement in their workforce and allow them to tailor

engagement strategies for different segments of their workforce depending on their specific

characteristics.

Presenting engagement results

As discussed earlier in this paper, one of the problematic features of many engagement models

is the use of the percentage of ‘engaged’ or ‘disengaged’ staff in the workplace as the key

engagement metric in an organisation. This suggests two things: first, that the concept of

engagement can be measured with a degree of precision that some would argue is not possible

to achieve with a self–report survey44 and second, that there is some fixed point at which an

employee becomes engaged (or disengaged) and their workplace behaviour subsequently

changes.

The idea of an absolute measure of engagement is unrealistic for two reasons. Firstly,

engagement is a psychosocial concept and therefore highly subjective and highly individual.

Secondly, almost all methods of measuring employee engagement use self-report survey that

are, irrespective of the content, subjective and prone to some degree of error related to the

method of the data collection. There are both statistical and methodological means of

mitigating error so this should not discourage attempts to measure engagement, but it does

substantially weaken any claims that might be made about absolute levels of engagement either

in individuals or organisations.

Finally, as demonstrated here, employee engagement involves a set of complex relationships

between the employee and the workplace. To suggest it can be described by a single index fails

to recognise the complexity of these relationships. Engagement measures need to reflect the

multi-dimensional nature of the relationship between an employee and their work and it is

unlikely that overall engagement can be presented in something as singular as the percentage of

engaged staff. Rather one is tempted to ask, “engaged with what aspect of work?”

While making absolute statements about levels of engagement has significant flaws, making

relative statements are significantly less affected by the fundamental nature of engagement or

44

The self-report survey is by far the most common means of measuring employee engagement.

19

the method used to measure engagement. As a result, the APS Engagement model eschews

reporting percentages of (dis)engaged staff. Instead engagement levels are reported on a

common zero to ten index for each component of engagement. This avoids some of the

criticisms made regarding making absolute statements about engagement. Secondly, the zero

to ten point index allows for employees to have varying levels of engagement with different

components of their workplace. For example, one employee might be highly engaged with their

job but less engaged with their team while another employee might be more engaged with their

team than their job. Both might be considered ‘engaged’ staff, however, they are different in

their engagement with their workplace. By reporting engagement levels on this common scale,

meaningful comparisons (i.e., relative statements) can be made across the different elements of

engagement.

By reporting engagement scores on a common scale, meaningful comparisons can be made

either within an agency over time, across different segments of an agency workforce, across

different segments of the APS workforce (e.g., age groups, sex, etc.), and across agencies

within the APS. Making comparisons against “benchmarks” like these can be useful for APS

managers and HR practitioners but they require context. Comparison across different agencies

might be misleading if the natures of the agencies are substantially different or if the context for

the agencies is different (e.g., if one agency had recently undergone a major restructure).

Comparisons within an agency over time are particularly useful because they provide one way

for APS managers and HR practitioners to test what effect their engagement interventions have

had.

Applying the Results of the APS Engagement Model

The purpose of any workforce research in the APS is to improve our understanding in order to

guide managers and HR professionals in the development of strategies that will improve some

aspect of the workforce or workplace that will lead to improvements in productivity and

therefore better outcomes for APS clients.

Because the Model provides a multi-dimensional view of employee engagement, it allows

managers to develop a more sophisticated understanding of the engagement issues in their

organisation. Similarly, identification of clear antecedents of engagement supports the

development of tailored strategies for addressing engagement in the workplace; an agency with

low levels of job engagement due primarily to low job challenge might invest in job enrichment

strategies, whereas another agency with high levels of job challenge, but lower agency

engagement due to limited learning and development opportunities might gain greater value

from investing in a learning and development strategy.

The identification of a suite of measureable consequences of employee engagement in the form

of observable organisational behaviours will allow agencies to tailor engagement strategies that

target these specific outcomes. For example, if workplace psychological injury claims were

identifiable as related to specific elements of employee engagement, managers in an agency

with high claim rates might develop an engagement strategy that targets these elements of

engagement specifically with the aim of reducing the claim rate. Work remains to be done to

identify these consequences and the relationships between the antecedents of engagement and

20

their consequences. However, once relationships and consequences have been identified they

will provide APS managers and HR practitioners with a very sophisticated model for

addressing key organisational capability issues in their workplace.

Limitations and further research

There are some limitations to this work; primary among these is that while the Survey provided

good coverage of the aspects of the hypothesised engagement model, it wasn’t developed to

measure this specific model of employee engagement. As a result, the work reported here

represents an exercise in fitting an existing theoretical model of employee engagement to a

different existing set of data. The fact that the model fits the data well suggests there is a degree

of robustness to the model that provides a high degree of confidence for adapting it as the APS

Employee Engagement Model. It does, however, also suggest that there is potential for future

refinement of the model as described in this paper.

The drivers and outcomes of engagement

Having identified a model of engagement that gives a greater understanding of the nature of

engagement in the APS and shows the relationships among its elements, the next key is to

identify the drivers (or antecedents) and outcomes (or consequences) of engagement. What

aspects of working in the APS lead to higher levels of job identification, for example, and

hence job engagement? And what impact will improved job engagement have on employee

performance and availability (retention, use of sick leave, etc.)

To deliver a useable outcome for APS managers and HR practitioners, the APS Employee

Engagement Model must be able to show a clear link between those aspects of the workplace

that influence or drive engagement and the subsequent impact on workplace outcomes. Figure 1

above shows this link graphically, but there is now a need to test this empirically. This will also

test the theoretical strength of the APS Employee Engagement Model and identify its utility to

the APS.

The compensatory nature of engagement

The nature of the relationships among the elements of engagement suggests that there may be a

compensatory nature to engagement in the APS that would help managers and HR practitioners

better tailor engagement strategies to their specific context. The hypothesised compensatory

nature of engagement needs further investigation to determine whether it exists and, if so, how

it can be used to better understand and improve engagement in the APS.

Trust and engagement

Trust has been hypothesised as a key element in the APS Employee Engagement model and

although there is a substantial body of literature on the importance of trust in the workplace, it’s

contribution to engagement in the APS needs to be examined to determine what role it plays

and how the APS might respond to trust in the workplace.

21

Other elements of engagement in the APS

There is also scope for future work examining other elements of employee engagement. The

APS Employee Engagement Model has been adapted from one developed primarily for the

private sector and there is good argument that substantial differences exist between the two

sectors. As a minimum, the relationship between the Model and the concept of public service

motivation would warrant further examination.

Summary

The APS Employee Engagement Model was developed after an examination of the literature on

employee engagement identified an existing model of employee engagement that met the needs

of the APS and was subsequently adapted for the APS. This model is based on the assumption

that employee’s relationship with work is multi-dimensional and characterised by reciprocity

and trust. It recognises that these relationships can vary across the APS, and gives APS

managers and HR practitioners a sophisticated understanding of the engagement issues specific

to their workplace so that they can develop engagement strategies tailored to their specific

context.

There are still a number of steps required to complete the development of the model. The first

is to identify drivers of engagement in the APS and the subsequent impacts on APS

organisational performance. Second, the compensatory nature of the model will need to be

tested: will different segments of the APS workforce demonstrate different levels of

engagement on the different elements of engagement? The relationship between trust and

engagement also needs further examination.

Finally, possible extensions to the model need to be considered. The current model was

developed using existing item sets from the APS Employee survey, and while the approach

taken has been psychometrically rigorous, it has not had the benefit of the exploration of other

concepts that might contribute to the understanding of employee engagement. For example, the

concept of public service motivation is one that warrants further consideration for how it relates

to the concept of employee engagement in the public service.

22

Appendix A: APS Employee Engagement Model Initial Item

Sets

Items related to the Job component of the APS Employee Engagement Model

Please rate your level of agreement with the following statements regarding your current job:

- I enjoy the work in my current job.

- I am motivated to do the best possible work that I can.

- I do my work for the satisfaction I experience from taking on interesting challenges.

- When needed, I am willing to put in the extra effort to get a job done.

- My job allows me to utilise my skills, knowledge and abilities.

- My work has become a fundamental part of who I am.

- Overall, I am satisfied with my job.

- My current job will help my career aspirations.

- My job gives me a feeling of personal accomplishment.

- I have a clear understanding of how my own job contributes to my work team’s role.

- I stay in my current job for the salary it provides me with.

- I receive adequate recognition for my work contributions and accomplishments.

- My job gives me the opportunity to work on the tasks I do best.

- I clearly understand what is expected of me in this job.

- I have the authority (e.g. the necessary delegation(s), autonomy, level of responsibility) to

do my job effectively.

- I want to succeed at my job so others will think highly of me.

- I receive adequate feedback on my performance to enable me to deliver required results.

- I am constantly looking for ways to do my job better.

- I am satisfied with the recognition I receive for doing a good job.

- I am fairly remunerated for the work that I do.

- I frequently try to help others who have heavy workloads.

- I am motivated at work because it helps me achieve my career goals.

- I would be more productive if there was less ‘red tape’ (e.g. regulatory or administrative

processes).

- I receive appropriate training and/or have access to information that enables me to meet

my recordkeeping responsibilities.

23

Please indicate your level of satisfaction with EACH of the following workplace attributes in your

current job:

- Duties/expectations made clear

- Regular feedback/recognition for effort

- Chance to be innovative

- Chance to make a useful contribution to society

- Seeing tangible results from my work

- Opportunities to utilise my skills

- Opportunities to develop my skills

- Good working relationships

- Appropriate workload

- Remuneration package (e.g. salary, superannuation)

- Opportunities for career development

- Interesting work provided

- Flexible working arrangements

- Good manager

- Appropriate level of autonomy in my job

Items related to the Team component of the APS Employee Engagement Model

Please rate your level of agreement with the following statements regarding your immediate

work group:

- The people in my work group feel they are valued for their contribution.

- The people in my work group use time and resources effectively.

- The people in my work group cooperate to get the job done.

- I feel that my own ideas are genuinely considered when strategies, goals or tasks are being

set for my work group.

- The people in my work group share job knowledge with each other.

- The people in my work group are honest, open and transparent in their dealings.

- The people in my work group treat each other with respect.

- The people in my work group resolve conflict quickly when it arises.

- I have a clear understanding of how my work group’s role contributes to my agency’s

strategic directions.

Items related to the Supervisor component of the APS Employee Engagement Model

Please rate your level of agreement with the following statements regarding your supervisor:

24

- My supervisor ensures fair access to developmental opportunities for employees in my

work group.

- My supervisor encourages me to build the capabilities and/or skills required for new job

roles.

- My supervisor appropriately deals with employees that perform poorly.

- My supervisor demonstrates honesty and integrity.

- My supervisor works effectively and sensitively with people from diverse backgrounds.

- My supervisor delegates work effectively.

- My supervisor shows concern for the welfare of his/her staff.

- My supervisor draws the best out of his/her staff.

- My supervisor encourages and manages innovation.

- My supervisor provides effective feedback.

Items related to the Agency component of the APS Employee Engagement Model

Please rate your level of agreement with the following statements regarding the senior leaders

(i.e. the Senior Executive Service [SES]) in your agency:

- In my agency, the leadership is of a high quality.

- My agency is well managed.

- In my agency, communication between senior leaders and other employees is effective.

- In my agency, senior leaders are receptive to ideas put forward by other employees.

- In my agency, senior leaders discuss with staff how to respond to future challenges.

- In my agency, the most senior leaders are sufficiently visible (e.g. can be seen in action).

Please rate your level of agreement with the following statements regarding aspects of your

agency’s working environment:

- My agency is a good place to work.

- In general, employees in my agency effectively manage conflicts of interest.

- In general, employees in my agency appropriately assess risk.

- Employees in my agency feel they are valued for their contribution.

- My agency places a high priority on the learning and development of employees.

- My agency operates with a high level of integrity.

- My agency deals with underperformance effectively.

- My agency encourages the public to participate in shaping and administering policy (e.g.

seeks and uses feedback, consults and engages communities on issues affecting them).

25

- Working at my agency is important to the way that I think of myself as a person.

- When someone praises the accomplishments of my agency, it feels like a personal

compliment to me.

- When I talk about my agency, I usually say “we” rather than “they”.

- My agency routinely applies merit in decisions regarding engagement and promotion.

- My agency promotes and supports good record keeping practices.

- My workplace provides realistic performance expectations.

- My workplace provides increased knowledge and/or experience in the job.

- My workplace provides access to effective learning and development.

- My workplace provides good working relationships with my manager and colleagues.

- Overall, my agency has sound governance processes for effective decision making.

- I am satisfied with my non-monetary employment conditions (e.g. leave, flexible work

arrangements, other benefits).

- I am well paid compared to what I would receive in other agencies.

- My agency provides an ethical working environment.

26