Emotional, Psychological and Mental Health (EPMH) disability

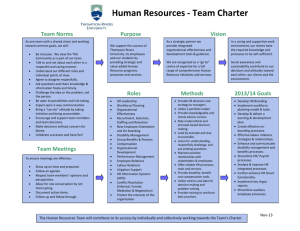

advertisement