Text: Bullying in American Schools – Editors: Espelage, D. L.

advertisement

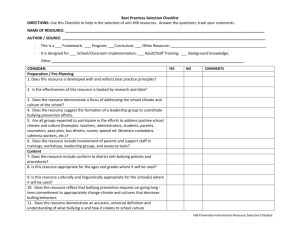

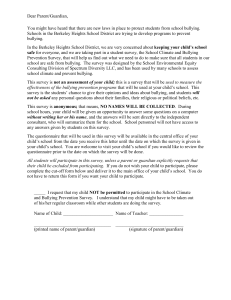

Text: Bullying in American Schools – Editors: Espelage, D. L., Swearer, S. M. (2004) Espelage – Univ. of Ill. Swearer – Univ. of Nebraska _____________________________________________________________________________________ Bullying v. Harassment Harassment: sex, race, color, national origin/ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, or disability “protected categories” (verbal, written, graphic or physical conduct) Bullying: Intentional electronic, written verbal, or physical act or series of acts by a student or groups of students 1. Directed at another student or students who typically are less physically or socially powerful; 2. Which occurs in or outside a school setting; and 3. That is severe, persistent or pervasive; and a. Substantially interfering with a student’s education b. Creating a threatening environment; or c. Substantially disrupting the orderly operation of the school Overview **p. 1 – Much of our knowledge about bullying behaviors comes from research conducted over the past several decades in Europe, Australia, and Canada. Research in the US has lagged behind. The book seeks to fill the void by forwarding research about bullying across contexts that has been conducted with participants in the US. The authors argue that bullying has to be understood across individual, family, peer, school, and community contexts. In order to develop and implement effective bullying prevention and intervention programs, we must understand the social ecology that establishes and maintains bullying and victimization behaviors. _____________________________________________________________________________________ Ecology **p. 2 - The idea that multiple environments influence individuals is not a new concept. p. 3 – In a nutshell, bullying does not occur in isolation. This phenomenon is encouraged and/or inhibited as a result of the complex relationships between the individual, family, peer group, school, community, and culture. p. 4 – Interventions that do not target the multiple environments in which youth exist are likely less effective than interventions that address the social ecology (Kerns & Prinz, 2002). This assertion is related to the consistent findings that youth are who are involved in aggressive behaviors experience problems in multiple areas, including the family, peer group, school, and community. p. 4 – Thus, assessment of the bullying phenomenon must utilize multiple methods of assessment, use multiple informants, and include assessments across contexts. _____________________________________________________________________________________ Unique School Ecology **p. 4 – There are over 300 published violence prevention school-based programs (Howard, Flora, & Griffin, 1999); however, less than a quarter of these programs are empirically validated. How are schools to choose which program may be best for their school ecology? p. 2 – Only one large-scale study on bullying in the US has been conducted (Nansel, Overpeck, Pilla, Ruan, Simons-Morton, & Scheidt, 2011). 15,686 students 6th -10th grader. Differences in bullying across urban, suburban, and rural areas were not found. p. 5 – Every school is defined by its own unique ecology. As has been previously articulated, schools should conduct an individual needs assessment and then choose school-based interventions based on the results of their own data (Boxer & Dubow, 2001). _____________________________________________________________________________________ Gender Differences p. 15 – Are boys more aggressive than girls? Although a tremendous amount of research over the last several decades supports an answer of “yes” (Block, 1983; Parke & Slaby, 1983), more recent research would also support an answer of “it depends” (Knight, Guthrie, Page, & Fabes, 2002). Contextual factors such as the definition of aggression, the method of assessment employed, and the age of the child/adolescent. p. 16 – despite the remarkable increase in the percentage of female offenders in the US (Snyder & Sickmund, 1999), the disparity in male and female offending is still very large; males offend at much higher rates than females do. p. 16 – some scholars argue that male aggression and offending should have a higher priority, based on the higher rate, and therefore are included in more research endeavors than females, when studying aggression and are therefore over-represented in samples. p. 16 – a second trend in the empirical literature followed the semial work by Crick and Grtpeter (1995). In this investigation, “relational aggression” emerged as a form of aggression thought to be more characteristic of girls in which the goal is to hurt other by damaging their reputation or their relationships. p. 16 – The gender paradox postulates that although females have lower prevalence rates of aggression and antisocial behavior than males, they are in fact at greater risk for psychological maladjustment. Therefore, we argue that in order to continue moving forward with prevention and intervention efforts to curb aggression and bulling in schools, we must attend to the social contexts that promote and maintain gender differences in aggression. _____________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________ Depression **p. 18 – depression has been found to be a common symptom experienced by male and female victims of bullying (Callagan & Joseph 1995; Neary & Joseph, 1994). Furthermore, Craig (1998) found higher depression levels for girls in comparison to boys who were victimized. p. 18 – depression is not, however, unique to victims only. Clinically elevated depression levels have been found for both male and female student who bully their peers. (Austin & Joseph, 1996; Slee, 1995). p. 18 – Bully-victims, those students who bully and have been bullied, have also been found to have higher rates of depression than bullies (Austin & Joseph, 1996), and in other studies, bully-victims report higher depression levels than victims (Swearer, Song, Cary, Eagle, & Mickelson, 2001). Anger ** p. 18 – Dodge, 1991; Price & Dodge, 1989) distinguished between reactive and proactive aggression. Generally, reactive aggression reflects an angry and volatile approach to others, whereas proactive aggression uses aggressive acts to meet a person’s goals and might not involve an angry reaction to a specific precipitating event. p. 18 – Some researchers have conceptualized bullying as proactive aggression because student who bully do so to attain social position and maintain control over others. p. 18 – However, in a more recent study of 558 middle school students, anger was found to be the strongest predictor of bullying (Bosworth, Espelage, & Simon, 1999). The results were significant for both males and females. _____________________________________________________________________________________ Anxiety ** p. 19 –Anxiety is also a salient mental-health concern that should be considered in intervention planning for bullies, victims, and bully-victims. p. 19 – Little research has been conducted specifically on anxiety and bulling, the research that has been conducted yielded inconsistent findings. (Craig, 1998; Olweus, 1994; Slee, 1994) – victims of bullying have higher rates of anxiety than bullies. (Duncan, 1999; Swearer et al., 1999) – found bully-victims have higher levels of anxiety when compared to bullies or victims _____________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________ Empathy ** p. 20 – Many bullying programs include empathy training based on the extensive literature documenting the role of empathy in suppressing aggression (Miller & Eisnberg, 1998). p. 20 – research suggests that self-declared bullies sometimes report feeling sorry after bullying peers (Borg, 1998); however, many bullying prevention program assume these students lack empathy. _____________________________________________________________________________________ Social Skills Deficit vs. Theory of Mind ** p. 19 - One of the most influential explanatory models of aggression is based on social information processing (Crick & Dodge, 1994; Dodge & Coie, 1987). This model posits that impairment in social problem-solving is implicated in the development of aggression. p. 19 – research has found that aggressive individuals are more likely to show encoding problems such as hostile attribution error, and deficits at the level of representation, such as poor understanding of others’ mental states (Crick & Dodge, 1994). However more recently, scholars have begun to question whether this model applies to all types of aggression, such as lying and spreading rumors that lead to the victim’s exclusion from the group, and that physical violence is in most cases carefully planned, it is plausible that at least some bullies have a social understanding of their behavior. p. 19 – following this logic Sutton, Smith, & Swettenham, (1999) challenged the social skills deficit model approach to bullying. They argue some bullies understand people very well and use this understanding to their advantage. p. 19 – These authors conceptualized their arguments using the framework of Theory of Mind, a concept that refers to one’s ability to attribute mental states to other and oneself (Leslie, 1987). Using this framework, the authors contend that some bullies may possess a theory of mind because they target vulnerable children who will tolerate victimization and who are not likely to receive support from peers (Salmivalli, Lagerspetz, Bjorkqvist, Osterman, & Kaukiainen, 1996). There is preliminary evidence that not all bullies lack social skills. _____________________________________________________________________________________