Final Keynote Panel

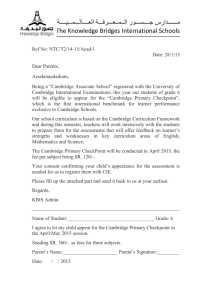

advertisement