Eruption of AD 79

Tallinn University

Baltic Film and Media School

Laura kõiv

Pompeii and Vesuv

Research

Tallinn 2014

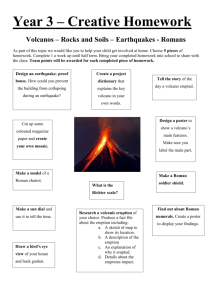

Content

Scientific analysis of the eruption

Later eruptions from the 3rd to the 19th century

Introduction

1 Pompeii

For the modern Italian city. Pompeii is located in Italy(Figure 1 Locatio)

Pompei, Province of Naples, Campania, Italy Coordinates

40°45′0″N

14°29′10″ECoordinates: 40°45′0″N 14°29′10″E Area 64 to 67 ha (170 acres)

Figure 1 Location

History:Founded 6th–7th century BC

Abandoned 79 AD

Figure 2. View into a narrow street of Pompeii.

1.1

Region

The city of Pompeii was an ancient Roman town-city near modern Naples in the Italian region of Campania, in the territory of the comune of Pompei. Pompeii, along with

Herculaneum and many villas in the surrounding area, was mostly destroyed and buried under

4 to 6 m (13 to 20 ft) of ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

Researchers believe that the town was founded in the seventh or sixth century BC by the

Osci or Oscans and was captured by the Romans in 80 BC. By the time of its destruction, 160 years later, its population was probably approximately 20,000, and the city had a complex water system, an amphitheatre, gymnasium and a port.

The eruption was cataclysmic for the town. Evidence for the destruction originally came from a surviving letter by Pliny the Younger, who saw the eruption from a distance and described the death of his uncle Pliny the Elder, an admiral of the Roman fleet, who tried to rescue citizens. The site was lost for about 1,500 years until its initial rediscovery in 1599 and broader rediscovery almost 150 years later by Spanish engineer Rocque Joaquin de Alcubierre in 1748.[1] The objects that lay beneath the city have been well preserved for centuries because of the lack of air and moisture. These artifacts provide an extraordinarily detailed insight into the life of a city during the Pax Romana. During the excavation, plaster was used to fill in the voids between the ash layers that once held human bodies. This allowed one to see the exact position the person was in when he or she died.

Pompeii has been a tourist destination for over 250 years. Today it has UNESCO World

Heritage Site status and is one of the most popular tourist attractions of Italy, with approximately 2.5 million visitors every year

1.2

Geography

The Temple of Jupiter with Vesuvius in the distance The ruins of Pompeii are located near the modern suburban town of Pompei (nowadays written with one 'i'). It stands on a spur formed by a lava flow to the north of the mouth of the Sarno River (known in ancient times as the Sarnus).

Today it is some distance inland, but in ancient times it would have been nearer to the coast. Pompeii is about 8 km (5.0 mi) away from Mount Vesuvius. It covered a total of 64 to

67 hectares (170 acres) and was home to approximately 11,000 to 11,500 people on the basis of household counts.[4] It was a major city in the region of Campania.

1.3

History

1.3.1

Early history

The archaeological digs at the site extend to the street level of the 79 AD volcanic event; deeper digs in older parts of Pompeii and core samples of nearby drillings have exposed layers of jumbled sediment that suggest that the city had suffered from other seismic events before the eruption. Three sheets of sediment have been found on top of the lava that lies below the city and, mixed in with the sediment, archaeologists have found bits of animal bone, pottery shards and plants. Carbon dating has determined the oldest of these layers to be from the 8th–6th centuries BC (around the time the city was founded). The other two strata are separated either by well-developed soil layers or Roman pavement, and were laid in the

4th century BC and 2nd century BC. It is theorized that the layers of the jumbled sediment were created by large landslides, perhaps triggered by extended rainfall.

The town was founded around the 6th-7th century BC by the Osci or Oscans, a people of central Italy, on what was an important crossroad between Cumae, Nola and Stabiae. It had already been used as a safe port by Greek and Phoenician sailors. According to Strabo,

Pompeii was also captured by the Etruscans, and in fact recent[timeframe?] excavations have shown the presence of Etruscan inscriptions and a 6th-century BC necropolis. Pompeii was captured for the first time by the Greek colony of Cumae, allied with Syracuse, between 525 and 474 BC.

In the 5th century BC, the Samnites conquered it (and all the other towns of Campania); the new rulers imposed their architecture and enlarged the town. After the Samnite Wars (4th century BC), Pompeii was forced to accept the status of socium of Rome, maintaining, however, linguistic and administrative autonomy. In the 4th century BC, it was fortified.

Pompeii remained faithful to Rome during the Second Punic War.

The present Temple of Apollo was built in the 2nd century BC as the city's most important religious structure

Pompeii took part in the war that the towns of Campania initiated against Rome, but in 89

BC it was besieged by Sulla. Although the blunts of the Social League, headed by Lucius

Cluentius, helped in resisting the Romans, in 80 BC Pompeii was forced to surrender after the conquest of Nola, culminating in many of Sulla's veterans being given land and property, while many of those who went against Rome were ousted from their homes. It became a

Roman colony with the name of Colonia Cornelia Veneria Pompeianorum. The town became an important passage for goods that arrived by sea and had to be sent toward Rome or

Southern Italy along the nearby Appian Way.

It was fed with water by a spur from Aqua Augusta (Naples) built c. 20 BC by Agrippa; the main line supplied several other large towns, and finally the naval base at Misenum. The castellum in Pompeii is well preserved, and includes many details of the distribution network and its controls.

The excavated city offers a snapshot of Roman life in the 1st century, frozen at the moment it was buried on 24 August AD 79.[7] The forum, the baths, many houses, and some out-oftown villas like the Villa of the Mysteries remain well preserved.

Details of everyday life are preserved. For example, on the floor of one of the houses

(Sirico's), a famous inscription Salve, lucru (Welcome, profit), perhaps humorously intended, indicates a trading company owned by two partners, Sirico and Nummianus (but this could be a nickname, since nummus means coin, money). Other houses provide details concerning professions and categories, such as for the "laundry" workers (Fullones). Wine jars have been found bearing what is apparently the world's earliest known marketing pun (technically a blend), Vesuvinum (combining Vesuvius and the Latin for wine, vinum).

The numerous graffiti carved on the walls and inside rooms provides a wealth of information regarding Vulgar Latin, i.e. the form of Latin spoken colloquially rather than the heightened literary register evoked by the classical writers.

In 89 BC, after the final occupation of the city by Roman General Lucius Cornelius Sulla,

Pompeii was finally annexed to the Roman Republic. During this period, Pompeii underwent a vast process of infrastructural development, most of which was built during the Augustan period. These include an amphitheatre, a palaestra with a central natatorium or swimming pool, and an aqueduct that provided water for more than 25 street fountains, at least four public baths, and a large number of private houses (domūs) and businesses. The amphitheatre

has been cited by modern scholars as a model of sophisticated design, particularly in the area of crowd control.

The aqueduct branched out through three main pipes from the Castellum Aquae, where the waters were collected before being distributed to the city; in case of extreme drought, the water supply would first fail to reach the public baths (the least vital service), then private houses and businesses, and when there would be no water flow at all, the system would fail to supply the public fountains (the most vital service) in the streets of Pompeii. The pools in

Pompeii were used mostly for decoration.

The large number of well-preserved frescoes provide information on everyday life and have been a major advance in art history of the ancient world, with the innovation of the

Pompeian Styles (First/Second/Third Style). Some aspects of the culture were distinctly erotic, including frequent use of the phallus as apotropaion or good-luck charm in various types of decoration. A large collection of erotic votive objects and frescoes were found at

Pompeii. Many were removed and kept until recently in a secret collection at the University of Naples.

At the time of the eruption, the town may have had some 20,000 inhabitants, and was located in an area in which Romans had their holiday villas. Prof. William Abbott explains,

"At the time of the eruption, Pompeii had reached its high point in society as many Romans frequently visited Pompeii on vacations." It is the only ancient town of which the whole topographic structure is known precisely as it was, with no later modifications or additions.

Due to the difficult terrain, it was not distributed on a regular plan as most Roman towns were, but its streets are straight and laid out in a grid in the Roman tradition. They are laid with polygonal stones, and have houses and shops on both sides of the street. It followed its decumanus and its cardo, centered on the forum.

Besides the forum, many other services were found: the Macellum (great food market), the

Pistrinum (mill), the Thermopolium (sort of bar that served cold and hot beverages), and cauponae (small restaurants). An amphitheatre and two theatres have been found, along with a palaestra or gymnasium. A hotel (of 1,000 square metres) was found a short distance from the town; it is now nicknamed the "Grand Hotel Murecine".

In 2002, another discovery at the mouth of the Sarno River near Sarno revealed that the port also was populated and that people lived in palafittes, within a system of channels that suggested a likeness to Venice to some scientists.

1.4

AD 62–79

The inhabitants of Pompeii had long been used to minor quaking (indeed, the writer Pliny the Younger wrote that earth tremors "were not particularly alarming because they are frequent in Campania"), but on 5 February 62,[9] there was a severe earthquake which did considerable damage around the bay and particularly to Pompeii. It is believed that the earthquake would have registered between about 5 and 6 on the current Richter scale.

On that day in Pompeii there were to be two sacrifices, as it was the anniversary of

Augustus being named "Father of the Nation" and also a feast day to honour the guardian spirits of the city. Chaos followed the earthquake. Fires, caused by oil lamps that had fallen during the quake, added to the panic. Nearby cities of Herculaneum and Nuceria were also affected.

Temples, houses, bridges, and roads were destroyed. It is believed that almost all buildings in the city of Pompeii were affected. In the days after the earthquake, anarchy ruled the city, where theft and starvation plagued the survivors. In the time between 62 and the eruption in

79, some rebuilding was done, but some of the damage had still not been repaired at the time of the eruption.[10] Although it is unknown how many, a considerable number of inhabitants moved to other cities within the Roman Empire while others remained and rebuilt.

An important field of current research concerns structures that were being restored at the time of the eruption (presumably damaged during the earthquake of 62). Some of the older, damaged, paintings could have been covered with newer ones, and modern instruments are being used to catch a glimpse of the long hidden frescoes. The probable reason why these structures were still being repaired around seventeen years after the earthquake was the increasing frequency of smaller quakes that led up to the eruption.

1.5

Eruption of Vesuvius

By the 1st century AD, Pompeii was one of a number of towns located near the base of the volcano, Mount Vesuvius. The area had a substantial population which grew prosperous from the region's renowned agricultural fertility. Many of Pompeii's neighboring communities, most famously Herculaneum, also suffered damage or destruction during the 79 eruption. The eruption occurred on August 24, just one day after Vulcanalia, the festival of the Roman god of fire, including that from volcanoes.

Pompeii and other cities affected by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. The black cloud represents the general distribution of ash and cinder. Modern coast lines are shown.

A multidisciplinary volcanological and bio-anthropological study of the eruption products and victims, merged with numerical simulations and experiments, indicate that at Vesuvius and surrounding towns heat was the main cause of death of people, previously believed to have died by ash suffocation. The results of the study, published in 2010, show that exposure to at least 250 °C (482 °F) hot surges at a distance of 10 kilometres (6 miles) from the vent was sufficient to cause instant death, even if people were sheltered within buildings.

The people and buildings of Pompeii were covered in up to twelve different layers of tephra, in total 25 meters deep, which rained down for about 6 hours. Pliny the Younger provided a first-hand account of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius from his position across the

Bay of Naples at Misenum, in a version which was written 25 years after the event. His uncle,

Pliny the Elder, with whom he had a close relationship, died while attempting to rescue stranded victims. As Admiral of the fleet, Pliny the Elder had ordered the ships of the

Imperial Navy stationed at Misenum to cross the bay to assist evacuation attempts.

Volcanologists have recognised the importance of Pliny the Younger's account of the eruption by calling similar events "Plinian".

The eruption was documented by contemporary historians and is generally accepted as having started on 24 August 79, relying on one version of the text of Pliny's letter. However the archeological excavations of Pompeii suggest that the city was buried about three months later.[13] This is supported by another version of the letter[14] which gives the date of the eruption as November 23.

People buried in the ash appear to be wearing warmer clothing than the light summer clothes that would be expected in August. The fresh fruit and vegetables in the shops are typical of October, and conversely the summer fruit that would have been typical of August was already being sold in dried, or conserved form. Wine fermenting jars had been sealed over, and this would have happened around the end of October. Coins found in the purse of a woman buried in the ash include one which features a fifteenth imperatorial acclamation among the emperor's titles. These cannot have been minted before the second week of

September. So far there is no definitive theory as to why there should be such an apparent discrepancy.

1.6

Rediscovery

Figure 3 "Garden of the Fugitives". Plaster casts of victims still in situ; many casts are in the Archaeological Museum of Naples.

After thick layers of ash covered the two towns, they were abandoned and eventually their names and locations were forgotten. The first time any part of them was unearthed was in

1599, when the digging of an underground channel to divert the river Sarno ran into ancient walls covered with paintings and inscriptions. The architect Domenico Fontana was called in; he unearthed a few more frescoes, then covered them over again, and nothing more came of the discovery. A wall inscription had mentioned a decurio Pompeii ("the town councillor of

Pompeii") but its reference to the long-forgotten Roman city was missed.

Fontana's act of covering over the paintings has been seen both as censorship – in view of the frequent sexual content of such paintings – and as a broad-minded act of preservation for later times as he would have known that paintings of the hedonistic kind later found in some

Pompeian villas were not considered in good taste in the climate of the counter-reformation.

Herculaneum was properly rediscovered in 1738 by workmen digging for the foundations of a summer palace for the King of Naples, Charles of Bourbon. Pompeii was rediscovered as the result of intentional excavations in 1748 by the Spanish military engineer Rocque Joaquin de Alcubierre.[16] These towns have since been excavated to reveal many intact buildings and wall paintings. Charles of Bourbon took great interest in the findings even after becoming king of Spain because the display of antiquities reinforced the political and cultural power of

Naples.

Karl Weber directed the first real excavations;[18] he was followed in 1764 by military engineer Franscisco la Vega. Franscisco la Vega was succeeded by his brother, Pietro, in

1804.During the French occupation Pietro worked with Christophe Saliceti.

Giuseppe Fiorelli took charge of the excavations in 1863.[21] During early excavations of the site, occasional voids in the ash layer had been found that contained human remains. It was Fiorelli who realized these were spaces left by the decomposed bodies and so devised the technique of injecting plaster into them to recreate the forms of Vesuvius's victims. This technique is still in use today, with a clear resin now used instead of plaster because it is more durable, and does not destroy the bones, allowing further analysis.

Many[who?] have theorized that Fontana found some of the famous erotic frescoes and, due to the strict modesty prevalent during his time, reburied them in an attempt at archaeological censorship. This view is bolstered by reports[by whom?] of later excavators who felt that sites they were working on had already been visited and reburied.[citation needed] Even many recovered household items had a sexual theme. The ubiquity of such imagery and items indicates that the sexual mores of the ancient Roman culture of the time were much more liberal than most present-day cultures, although much of what is described as erotic imagery (e.g., over-sized phalluses) was in fact fertility imagery.

This clash of cultures led to an unknown number of discoveries being hidden away again.

A wall fresco which depicted Priapus, the ancient god of sex and fertility, with his extremely enlarged penis, was covered with plaster, even the older reproduction below was locked away

"out of prudishness" and opened only on request and only rediscovered in 1998 due to rainfall.

In 1819, when King Francis I of Naples visited the Pompeii exhibition at the National

Museum with his wife and daughter, he was so embarrassed by the erotic artwork that he decided to have it locked away in a secret cabinet, accessible only to "people of mature age and respected morals". Re-opened, closed, re-opened again and then closed again for nearly

100 years, it was briefly made accessible again at the end of the 1960s (the time of the sexual revolution) and was finally re-opened for viewing in 2000. Minors are still allowed entry to the once secret cabinet only in the presence of a guardian or with written permission.

A large number of artifacts from Pompeii are preserved in the Naples National

Archaeological Museum.

1.7

Tourism

Pompeii has been a popular tourist destination for over 250 years; it was on the Grand

Tour. By 2008, it was attracting almost 2.6 million visitors per year, making it one of the most popular tourist sites in Italy. It is part of a larger Vesuvius National Park and was declared a

World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1997. To combat problems associated with tourism, the governing body for Pompeii, the Soprintendenza Archaeological di Pompei have begun issuing new tickets that allow for tourists to also visit cities such as Herculaneum and Stabiae as well as the Villa Poppaea, to encourage visitors to see these sites and reduce pressure on

Pompeii.

A paved street. The blocks in the road allowed pedestrians to cross the street without having to step onto the road itself which doubled up as Pompeii's drainage and sewage disposal system. The spaces between the blocks allowed horse-drawn carts to pass along the road.

Figure 4 The House of the Faun.

Pompeii is also a driving force behind the economy of the nearby town of Pompei. Many residents are employed in the tourism and hospitality business, serving as taxi or bus drivers, waiters or hotel operators. The ruins can be easily reached on foot from the Circumvesuviana train stop called Pompei Scavi, directly at the ancient site. There are also car parks nearby.

Excavations in the site have generally ceased due to the moratorium imposed by the superintendent of the site, Professor Pietro Giovanni Guzzo. Additionally, the site is generally less accessible to tourists, with less than a third of all buildings open in the 1960s being available for public viewing today. Nevertheless, the sections of the ancient city open to the public are extensive, and tourists can spend several days exploring the whole site.

1.8

In popular culture

Book I of the Cambridge Latin Course teaches Latin while telling the story of a Pompeii resident, Lucius Caecilius Iucundus, from the reign of Nero to that of Vespasian. The book ends when Mount Vesuvius erupts, and Caecilius and his household are killed. The books have a cult following and students have been known to attempt to track down Caecilius's house during visits to Pompeii.

Pompeii was the setting for the British comedy television series Up Pompeii! and the movie of the series. Pompeii also featured in the second episode of the fourth season of revived BBC drama series Doctor Who, named "The Fires of Pompeii",[30] which featured

Caecilius as a character.

In 1971, the rock band Pink Floyd recorded the live concert film Pink Floyd: Live at

Pompeii, performing six songs in the ancient Roman amphitheatre in the city. The audience consisted only of the film's production crew and some local children.

Pompeii is a song by the British band Bastille, released 24 February 2013. The lyrics refer to the city and the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

1.9

Conservation

The objects buried beneath Pompeii were well-preserved for almost two thousand years.

The lack of air and moisture allowed for the objects to remain underground with little to no deterioration, which meant that, once excavated, the site had a wealth of sources and evidence for analysis, giving detail into the lives of the Pompeiians. However, once exposed, Pompeii has been subject to both natural and man-made forces which have rapidly increased their rate of deterioration.

Weathering, erosion, light exposure, water damage, poor methods of excavation and reconstruction, introduced plants and animals, tourism, vandalism and theft have all damaged the site in some way. Two-thirds of the city has been excavated, but the remnants of the city are rapidly deteriorating.

The concern for conservation has continually troubled archaeologists. The ancient city was included in the 1996 World Monuments Watch by the World Monuments Fund, and again in

1998 and in 2000. In 1996 the organization claimed that Pompeii "desperately need[ed] repair" and called for the drafting of a general plan of restoration and interpretation.[32] The

organization supported conservation at Pompeii with funding from American Express and the

Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

Today, funding is mostly directed into conservation of the site; however, due to the expanse of Pompeii and the scale of the problems, this is inadequate in halting the slow decay of the materials. An estimated US$335 million is needed for all necessary work on

Pompeii.[citation needed] A recent study has recommended an improved strategy for interpretation and presentation of the site as a cost-effective method of improving its conservation and preservation in the short term.

The 2,000-year-old Schola Armatorum (House of the Gladiators) collapsed on 6 November

2010. The structure was not open to visitors, but the outside was visible to tourists. There was no immediate determination as to what caused the building to collapse, although reports suggested water infiltration following heavy rains might have been responsible. There has been fierce controversy after the collapse, with accusations of neglect.

2 Mount Vesuvius

Figure 5 Province of Naples, Italy

Coordinates

40°49′N 14°26′ECoordinates: 40°49′N

14°26′E

Geology

Type

Somma volcano

Age of rock

25,000 years before present to 1944 age of volcano = c. 17,000 years to present

Volcanic arc/belt

Campanian volcanic arc

Last eruption

1913 to 1944

Mount Vesuvius (Italian: Monte Vesuvio, Latin: Mons Vesuvius) is a stratovolcano in the

Gulf of Naples, Italy, about 9 km (5.6 mi) east of Naples and a short distance from the shore.

It is one of several volcanoes which form the Campanian volcanic arc. Vesuvius consists of a

large cone partially encircled by the steep rim of a summit caldera caused by the collapse of an earlier and originally much higher structure.

Mount Vesuvius is best known for its eruption in AD 79 that led to the burying and destruction of the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. That eruption ejected a cloud of stones, ash and fumes to a height of 33 km (20.5 mi), spewing molten rock and pulverized pumice at the rate of 1.5 million tons per second, ultimately releasing a hundred thousand times the thermal energy released by the Hiroshima bombing.[1] An estimated 16,000 people died due to hydrothermal pyroclastic flows.[2] The only surviving eyewitness account of the event consists of two letters by Pliny the Younger to the historian Tacitus.

Vesuvius has erupted many times since and is the only volcano on the European mainland to have erupted within the last hundred years. Today, it is regarded as one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world because of the population of 3,000,000 people living nearby and its tendency towards explosive (Plinian) eruptions. It is the most densely populated volcanic region in the world.

2.1

Mythology

Vesuvius has a long historic and literary tradition. It was considered a divinity of the

Genius type at the time of the eruption of 79 AD: it appears under the inscribed name

Vesuvius as a serpent in the decorative frescos of many lararia, or household shrines, surviving from Pompeii. An inscription from Capua to IOVI VESVVIO indicates that he was worshipped as a power of Jupiter; that is, Jupiter Vesuvius.

The historian Diodorus Siculus relates a tradition that Hercules, in the performance of his labors, passed through the country of nearby Cumae on his way to Sicily and found there a place called "the Phlegraean Plain" (phlegraion pedion, "plain of fire"), "from a hill which anciently vomited out fire ... now called Vesuvius." It was inhabited by bandits, "the sons of the Earth," who were giants. With the assistance of the gods he pacified the region and went on. The facts behind the tradition, if any, remain unknown, as does whether Herculaneum was named after it. An epigram by the poet Martial in 88 AD suggests that both Venus, patroness of Pompeii, and Hercules were worshipped in the region devastated by the eruption of

79.Whether Hercules was ever considered some sort of patron of the volcano itself is debatable.

Figure 6 City of Naples with Mount Vesuvius at sunset

2.2

Origin of the name

Vesuvius was a name of the volcano in frequent use by the authors of the late Roman

Republic and the early Roman Empire. Its collateral forms were Vesaevus, Vesevus, Vesbius and Vesvius.[9] Writers in ancient Greek used Οὐεσούιον or Οὐεσούιος. Many scholars since then have offered an etymology. As peoples of varying ethnicity and language occupied

Campania in the Roman Iron Age, the etymology depends to a large degree on the presumption of what language was spoken there at the time. Naples was settled by Greeks, as the name Nea-polis, "New City", testifies. The Oscans, a native Italic people, lived in the countryside. The Latins also competed for the occupation of Campania. Etruscan settlements were in the vicinity. Other peoples of unknown provenance are said to have been there at some time by various ancient authors.

On the presumption that the language is Greek, Vesuvius might be a Latinization of the negative οὔ (ve) prefixed to a root from or related to the Greek word σβέννυμι = "I quench", in the sense of "unquenchable".[9][10] In another derivation it might be from ἕω "hurl" and

βίη "violence", "hurling violence", *vesbia, taking advantage of the collateral form.

Some other theories about its origin are:

From an Indo-European root, *eus- < *ewes- < *(a)wes-, "shine" sense "the one who lightens", through Latin or Oscan.

From an Indo-European root *wes = "hearth" (compare e.g. Vesta)

2.3

Physical appearance

Figure 7 A view of the crater wall of Vesuvius, with the city of Torre del Greco in the background

Vesuvius is a distinctive "humpbacked" mountain, consisting of a large cone (Gran Cono) partially encircled by the steep rim of a summit caldera caused by the collapse of an earlier and originally much higher structure called Monte Somma.[13] The Gran Cono was produced during the eruption of AD 79. For this reason, the volcano is also called Somma-Vesuvius or

Somma-Vesuvio.

The caldera started forming during an eruption around 17,000[14][15] (or 18,300)[16] years ago and was enlarged by later paroxysmal eruptions[17] ending in the one of AD 79.

This structure has given its name to the term "somma volcano", which describes any volcano with a summit caldera surrounding a newer cone.

The height of the main cone has been constantly changed by eruptions but is 1,281 m

(4,203 ft) at present. Monte Somma is 1,149 m (3,770 ft) high, separated from the main cone by the valley of Atrio di Cavallo, which is some 5 km (3.1 mi) long. The slopes of the mountain are scarred by lava flows but are heavily vegetated, with scrub and forest at higher altitudes and vineyards lower down. Vesuvius is still regarded as an active volcano, although its current activity produces little more than steam from vents at the bottom of the crater.

Vesuvius is a stratovolcano at the convergent boundary where the African Plate is being subducted beneath the Eurasian Plate. Layers of lava, scoria, volcanic ash, and pumice make up the mountain. Their mineralogy is variable, but generally silica-undersaturated and rich in potassium, with phonolite produced in the more explosive eruptions.

2.4

Formation

Vesuvius was formed as a result of the collision of two tectonic plates, the African and the

Eurasian. The former was subducted beneath the latter, deeper into the earth. As the watersaturated sediments of the oceanic African plate were pushed to hotter depths in the earth, the water boiled off and caused the melting point of the upper mantle to drop enough to create partial melting of the rocks. Because magma is less dense than the solid rock around it, it was pushed upward. Finding a weak place at the Earth's surface it broke through, producing the volcano.

The volcano is one of several which form the Campanian volcanic arc. Others include

Campi Flegrei, a large caldera a few kilometres to the north west, Mount Epomeo, 20 kilometres (12 mi) to the west on the island of Ischia, and several undersea volcanoes to the south. The arc forms the southern end of a larger chain of volcanoes produced by the subduction process described above, which extends northwest along the length of Italy as far as Monte Amiata in Southern Tuscany. Vesuvius is the only one to have erupted within recent history, although some of the others have erupted within the last few hundred years. Many are either extinct or have not erupted for tens of thousands of year

2.5

Eruptions

Mount Vesuvius has erupted many times. The famous eruption in 79 AD was preceded by numerous others in prehistory, including at least three significantly larger ones, the best known being the Avellino eruption around 1800 BC which engulfed several Bronze Age settlements. Since 79 AD, the volcano has also erupted repeatedly, in 172, 203, 222, possibly

303, 379, 472, 512, 536, 685, 787, around 860, around 900, 968, 991, 999, 1006, 1037, 1049, around 1073, 1139, 1150, and there may have been eruptions in 1270, 1347, and 1500.[17]

The volcano erupted again in 1631, six times in the 18th century, eight times in the 19th century (notably in 1872), and in 1906, 1929, and 1944. There has been no eruption since

1944, and none of the post-79 eruptions were as large or destructive as the Pompeian one.

The eruptions vary greatly in severity but are characterized by explosive outbursts of the kind dubbed Plinian after Pliny the Younger, a Roman writer who published a detailed description of the 79 AD eruption, including his uncle's death.[20] On occasion, eruptions from Vesuvius have been so large that the whole of southern Europe has been blanketed by ash; in 472 and 1631, Vesuvian ash fell on Constantinople (Istanbul), over 1,200 kilometres

(750 mi) away. A few times since 1944, landslides in the crater have raised clouds of ash dust, raising false alarms of an eruption.

2.6

Before AD 79

Scientific knowledge of the geologic history of Vesuvius comes from core samples taken from a 2,000 m (6,600 ft) plus bore hole on the flanks of the volcano, extending into

Mesozoic rock. Cores were dated by potassium-argon and argon-argon dating. The mountain started forming 25,000 years ago. Although the area has been subject to volcanic activity for at least 400,000 years, the lowest layer of eruption material from the Somma mountain lies on top of the 34,000 year-old Campanian Ignimbrite produced by the Campi Flegrei complex, and was the product of the Codola plinian eruption 25,000 years ago.

It was then built up by a series of lava flows, with some smaller explosive eruptions interspersed between them. However, the style of eruption changed around 19,000 years ago to a sequence of large explosive plinian eruptions, of which the 79 AD one was the most recent. The eruptions are named after the tephra deposits produced by them, which in turn are named after the location where the deposits were first identified

The Basal Pumice (Pomici di Base) eruption, 18,300 years ago, VEI 6, saw the original formation of the Somma caldera. The eruption was followed by a period of much less violent, lava producing eruptions.

The Green Pumice (Pomici Verdoline) eruption, 16,000 years ago, VEI 5.

The Mercato eruption (Pomici di Mercato) — also known as Pomici Gemelle or Pomici

Ottaviano — 8000 years ago, VEI 6, followed a smaller explosive eruption around 11,000 years ago (called the Lagno Amendolare eruption).

The Avellino eruption (Pomici di Avellino), 3800 years ago, VEI 5, followed two smaller explosive eruptions around 5,000 years ago. The Avellino eruption vent was apparently 2 km west of the current crater, and the eruption destroyed several Bronze Age settlements of the

Apennine culture. Several carbon dates on wood and bone offer a range of possible dates of about 500 years in the mid-2nd millennium BC. In May 2001, near Nola, Italian archaeologists using the technique of filling every cavity with plaster or substitute compound recovered some remarkably well-preserved forms of perishable objects, such as fence rails, a bucket and especially in the vicinity thousands of human footprints pointing into the

Apennines to the north. The settlement had huts, pots, and goats. The residents had hastily

abandoned the village, leaving it to be buried under pumice and ash in much the same way that Pompeii was later preserved.[23][24] Pyroclastic surge deposits were distributed to the northwest of the vent, travelling as far as 15 km (9.3 mi) from it, and lie up to 3 m (9.8 ft) deep in the area now occupied by Naples.

The volcano then entered a stage of more frequent, but less violent, eruptions until the most recent Plinian eruption, which destroyed Pompeii.

The last of these may have been in 217 BC.[17] There were earthquakes in Italy during that year and the sun was reported as being dimmed by a haze or dry fog. Plutarch wrote of the sky being on fire near Naples and Silius Italicus mentioned in his epic poem Punica[26] that Vesuvius had thundered and produced flames worthy of Mount Etna in that year, although both authors were writing around 250 years later. Greenland ice core samples of around that period show relatively high acidity, which is assumed to have been caused by atmospheric hydrogen sulfide.

Figure 8 Fresco of Bacchus and Agathodaemon with Mount Vesuvius, as seen in Pompeii's House of the

Centenary.

The mountain was then quiet for hundreds of years and was described by Roman writers as having been covered with gardens and vineyards, except at the top which was craggy. The mountain may have had only one summit at that time, judging by a wall painting, "Bacchus and Vesuvius", found in a Pompeiian house, the House of the Centenary (Casa del

Centenario).

Several surviving works written over the 200 years preceding the 79 AD eruption describe the mountain as having had a volcanic nature, although Pliny the Elder did not depict the mountain in this way in his Naturalis Historia:[28]

The Greek historian Strabo (ca 63 BC–AD 24) described the mountain in Book V, Chapter

4 of his Geographica[29] as having a predominantly flat, barren summit covered with sooty,

ash-coloured rocks and suggested that it might once have had "craters of fire". He also perceptively suggested that the fertility of the surrounding slopes may be due to volcanic activity, as at Mount Etna.

In Book II of De Architectura,[30] the architect Vitruvius (ca 80-70 BC -?) reported that fires had once existed abundantly below the mountain and that it had spouted fire onto the surrounding fields. He went on to describe Pompeiian pumice as having been burnt from another species of stone.

Diodorus Siculus (ca 90 BC–ca 30 BC), another Greek writer, wrote in Book IV of his

Bibliotheca Historica that the Campanian plain was called fiery (Phlegrean) because of the mountain, Vesuvius, which had spouted flame like Etna and showed signs of the fire that had burnt in ancient history.[31]

2.7

Eruption of AD 79

In the year of 79 AD, Mount Vesuvius erupted in one of the most catastrophic and famous eruptions of all time. Historians have learned about the eruption from the eyewitness account of Pliny the Younger, a Roman administrator and poet.[32]

Mount Vesuvius spawned a deadly cloud of stones, ash and fumes to a height of 33 km

(20.5 mi), spewing molten rock and pulverized pumice at the rate of 1.5 Mt/s, ultimately releasing a hundred thousand times the thermal energy released by the Hiroshima bombing.[1] The towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum were destroyed by pyroclastic flows and the ruins buried under dozens of feet of tephra.[1][32] An estimated 16,000 people died from the eruption.

2.8

Precursors and foreshocks

The 79 AD eruption was preceded by a powerful earthquake seventeen years beforehand on February 5, AD 62, which caused widespread destruction around the Bay of Naples, and particularly to Pompeii.[33] Some of the damage had still not been repaired when the volcano erupted.[34] The deaths of 600 sheep from "tainted air" in the vicinity of Pompeii indicates that the earthquake of 62 may have been related to new activity by Vesuvius.

The Romans grew accustomed to minor earth tremors in the region; the writer Pliny the

Younger even wrote that they "were not particularly alarming because they are frequent in

Campania". Small earthquakes started taking place on August 20, 79[34] becoming more frequent over the next four days, but the warnings were not recognised.

2.9

Scientific analysis of the eruption

Reconstructions of the eruption and its effects vary considerably in the details but have the same overall features. The eruption lasted two days. The morning of the first day was perceived as normal by the only eyewitness to leave a surviving document, Pliny the

Younger. In the middle of the day an explosion threw up a high-altitude column from which ash began to fall, blanketing the area. Rescues and escapes occurred during this time. At some time in the night or early the next day pyroclastic flows in the close vicinity of the volcano began. Lights were seen on the mountain interpreted as fires. People as far away as Misenum fled for their lives. The flows were rapid-moving, dense and very hot, knocking down wholly or partly all structures in their path, incinerating or suffocating all population remaining there and altering the landscape, including the coastline. These were accompanied by additional light tremors and a mild tsunami in the Bay of Naples. By evening of the second day the eruption was over, leaving only haze in the atmosphere through which the sun shone weakly.

Figure 9Herculaneum and other cities affected by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. The black cloud represents the general distribution of ash and cinder. Modern coast lines are shown.

The latest scientific studies of the ash produced by Vesuvius reveals a multi-phase eruption.The initial major explosion produced a column of ash and pumice ranging between

15 kilometres (49,000 ft) and 30 kilometres (98,000 ft) high, which rained on Pompeii to the southeast but not on Herculaneum upwind. The chief energy supporting the column came from the escape of steam superheated by the magma, created from ground water seeping over time into the deep faults of the region.

Subsequently the cloud collapsed as the gases expanded and lost their capability to support their solid contents, releasing it as a pyroclastic surge, which reached Herculaneum but not

Pompeii. Additional explosions reinstituted the column. The eruption alternated between

Plinian and Peléan six times. Surges 3 and 4 are believed by the authors to have destroyed

Pompeii.[38] Surges are identified in the deposits by dune and cross-bedding formations, which are not produced by fallout.

Another study used the magnetic characteristics of over 200 samples of roof-tile and plaster fragments collected around Pompeii to estimate equilibrium temperature of the pyroclastic flow. The magnetic study revealed that on the first day of the eruption a fall of white pumice containing clastic fragments of up to 3 centimetres (1.2 in) fell for several hours.It heated the roof tiles up to 140 °C (284 °F). This period would have been the last opportunity to escape.

The collapse of the Plinian columns on the second day caused pyroclastic density currents

(PDCs) that devastated Herculaneum and Pompeii. The depositional temperature of these pyroclastic surges ranged up to 300 °C (572 °F). Any population remaining in structural refuges could not have escaped, as the city was surrounded by gases of incinerating temperatures. The lowest temperatures were in rooms under collapsed roofs. These were as low as 100 °C (212 °F).

2.10

The Two Plinys

The only surviving eyewitness account of the event consists of two letters by Pliny the

Younger to the historian Tacitus.[3] Pliny the Younger describes, amongst other things, the last days in the life of his uncle, Pliny the Elder. Observing the first volcanic activity from

Misenum across the Bay of Naples from the volcano, approximately 35 kilometres (22 mi), the elder Pliny launched a rescue fleet and went himself to the rescue of a personal friend. His nephew declined to join the party. One of the nephew's letters relates what he could discover from witnesses of his uncle's experiences.[44] In a second letter the younger Pliny details his own observations after the departure of his uncle.

The two men saw an extraordinarily dense cloud rising rapidly above the mountain. This cloud and a request by messenger for an evacuation by sea prompted the elder Pliny to order rescue operations in which he sailed away to participate. His nephew attempted to resume a normal life, but that night a tremor awoke him and his mother, prompting them to abandon the house for the courtyard. Further tremors near dawn caused the population to abandon the village and caused wave action in the Bay of Naples.

The early light was obscured by a black cloud through which shone flashes, which Pliny likens to sheet lightning, but more extensive. The cloud obscured Point Misenum near at hand and the island of Capraia (Capri) across the bay. Fearing for their lives, the population began to call to each other and move back from the coast along the road. A rain of ash fell, causing

Pliny to shake it off periodically to avoid being buried. Later that same day the ash stopped falling and the sun shone weakly through the cloud, encouraging Pliny and his mother to return to their home and wait for news of Pliny the Elder.

Pliny’s uncle Pliny the Elder was in command of the Roman fleet at Misenum, and had meanwhile decided to investigate the phenomenon at close hand in a light vessel. As the ship was preparing to leave the area, a messenger came from his friend Rectina (wife of Bassus) living on the coast near the foot of the volcano explaining that her party could only get away by sea and asking for rescue. Pliny ordered the immediate launching of the fleet galleys to the evacuation of the coast. He continued in his light ship to the rescue of Rectina's party.

He set off across the bay but in the shallows on the other side encountered thick showers of hot cinders, lumps of pumice and pieces of rock. Advised by the helmsman to turn back he stated "Fortune favors the brave" and ordered him to continue on to Stabiae (about 4.5 km from Pompeii).

Pliny the Elder and his party saw flames coming from several parts of the mountain. After staying overnight, the party was driven from the building by an accumulation of material, presumably, tephra, which threatened to block all egress. They woke Pliny, who had been napping and emitting loud snoring. They elected to take to the fields with pillows tied to their heads to protect them from rockfall. They approached the beach again but the wind prevented the ships from leaving. Pliny sat down on a sail that had been spread for him and could not rise even with assistance when his friends departed. Though Pliny the Elder died, his friends ultimately escaped by land.

In the first letter to Tacitus, Pliny the Younger suggested that his uncle's death was due to the reaction of his weak lungs to a cloud of poisonous, sulphurous gas that wafted over the group. However, Stabiae was 16 km from the vent (roughly where the modern town of

Castellammare di Stabia is situated) and his companions were apparently unaffected by the fumes, and so it is more likely that the corpulent Pliny died from some other cause, such as a stroke or heart attack.His body was found with no apparent injuries on the next day, after dispersal of the plume.

2.11

Casualties from the eruption

Figure 10 Pompeii, with Vesuvius towering above

Along with Pliny the Elder, the only other noble casualties of the eruption to be known by name were Agrippa (a son of the Jewish princess Drusilla and the procurator Antonius Felix) and his wife.

An estimated 16,000 citizens in the Roman vicinities of Pompeii and Herculaneum perished due to hydrothermal pyroclastic flows.[2][49][50] By 2003, around 1,044 casts made from impressions of bodies in the ash deposits had been recovered in and around Pompeii, with the scattered bones of another 100.[51] The remains of about 332 bodies have been found at Herculaneum (300 in arched vaults discovered in 1980).[52] What percentage these numbers are of the total dead or the percentage of the dead to the total number at risk remain completely unknown.

Thirty-eight percent of the 1,044 were found in the ash fall deposits, the majority inside buildings. These are thought to have been killed mainly by roof collapses, with the smaller number of victims found outside of buildings probably being killed by falling roof slates or by larger rocks thrown out by the volcano. The remaining 62% of remains found at Pompeii were in the pyroclastic surge deposits,[51] and thus were probably killed by them – probably from a combination of suffocation through ash inhalation and blast and debris thrown around. In contrast to the victims found at Herculaneum, examination of cloth, frescoes and skeletons show that it is unlikely that high temperatures were a significant cause. Herculaneum, which was much closer to the crater, was saved from tephra falls by the wind direction, but was buried under 23 metres (75 ft) of material deposited by pyroclastic surges. It is likely that most, or all, of the known victims in this town were killed by the surges.

People caught on the former seashore by the first surge died of thermal shock. No boats have been found, indicating they may have been used for the earlier escape of some of the population. The rest were concentrated in arched chambers at a density of as high as 3 persons per square meter. As only 85 metres (279 ft) of the coast have been excavated, the casualties waiting to be excavated may well be as high as the thousands.[53]

2.12

Later eruptions from the 3rd to the 19th century

Figure 11 An eruption of Vesuvius seen from Portici, by Joseph Wright (ca. 1774-6)

Since the eruption of 79 AD, Vesuvius has erupted around three dozen times. It erupted again in 203, during the lifetime of the historian Cassius Dio. In 472, it ejected such a volume of ash that ashfalls were reported as far away as Constantinople. The eruptions of 512 were so severe that those inhabiting the slopes of Vesuvius were granted exemption from taxes by

Theodoric the Great, the Gothic king of Italy. Further eruptions were recorded in 787, 968,

991, 999, 1007 and 1036 with the first recorded lava flows. The volcano became quiescent at the end of the 13th century and in the following years it again became covered with gardens and vineyards as of old. Even the inside of the crater was filled with shrubbery.

Vesuvius entered a new phase in December 1631, when a major eruption buried many villages under lava flows, killing around 3,000 people. Torrents of boiling water were also ejected, adding to the devastation. Activity thereafter became almost continuous, with relatively severe eruptions occurring in 1660, 1682, 1694, 1698, 1707, 1737, 1760, 1767,

1779, 1794, 1822, 1834, 1839, 1850, 1855, 1861, 1868, 1872, 1906, 1926, 1929, and 1944.

2.13

Eruptions in the 20th century

Figure 12 The March 1944 eruption of Vesuvius, by Jack Reinhardt, B-24 tailgunner in the USAAF during WWII

The eruption of April 7, 1906 killed over 100 people and ejected the most lava ever recorded from a Vesuvian eruption. Italian authorities were preparing to hold the 1908

Summer Olympics when Mount Vesuvius erupted, devastating the city of Naples. Funds were diverted to the reconstruction of Naples, so a new location for the Olympics was required.

London was selected for the first time to hold the Games which were held at White City alongside the Franco-British Exhibition, at the time the more noteworthy event. Berlin and

Milan were other candidates.

The last major eruption was in March 1944. It destroyed the villages of San Sebastiano al

Vesuvio, Massa di Somma, Ottaviano, and part of San Giorgio a Cremano.[54] From March

18 to 23, 1944, lava flows appeared within the rim. There were outflows. Small explosions then occurred until the major explosion took place on March 18, 1944.

At the time of the eruption, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) 340th

Bombardment Group was based at Pompeii Airfield near Terzigno, Italy, just a few kilometers from the eastern base of the mountain. The tephra and hot ash damaged the fabric control surfaces, the engines, the Plexiglas windshields and the gun turrets of the 340th's B-25

Mitchell medium bombers. Estimates ranged from 78 to 88 aircraft destroyed.

Figure 13 Ash is swept off the wings of an American B-25 Mitchell medium bomber of the 340th Bombardment

Group on March 23, 1944 after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

The eruption could be seen from Naples. Different perspectives and the damage caused to the local villages were recorded by USAAF photographers and other personnel based nearer to the volcano.

2.14

The future

Large plinian eruptions which emit lava in quantities of about 1 cubic kilometre (0.24 cu mi), the most recent of which overwhelmed Pompeii, have happened after periods of inactivity of a few thousand years. Subplinian eruptions producing about 0.1 cubic kilometres

(0.024 cu mi), such as those of 472 and 1631, have been more frequent with a few hundred years between them. Following the 1631 eruption until 1944 every few years saw a comparatively small eruption which emitted 0.001-0.01 km³ of magma. It seems that for

Vesuvius the amount of magma expelled in an eruption increases very roughly linearly with the interval since the previous one, and at a rate of around 0.001 cubic kilometres (0.00024 cu mi) for each year. This gives an extremely approximate figure of 0.06 cubic kilometres (0.014 cu mi) for an eruption after 60 years of inactivity.

Magma sitting in an underground chamber for many years will start to see higher melting point constituents such as olivine crystallising out. The effect is to increase the concentration of dissolved gases (mostly steam and carbon dioxide) in the remaining liquid magma, making the subsequent eruption more violent. As gas-rich magma approaches the surface during an eruption, the huge drop in pressure caused by the reduction in weight of the overlying rock

(which drops to zero at the surface) causes the gases to come out of solution, the volume of gas increasing explosively from nothing to perhaps many times that of the accompanying magma. Additionally, the removal of the lower melting point material will raise the

concentration of felsic components such as silicates potentially making the magma more viscous, adding to the explosive nature of the eruption.

Figure 14 The area around the volcano is now densely populated.

The government emergency plan for an eruption therefore assumes that the worst case will be an eruption of similar size and type to the 1631 VEI 4[59] one. In this scenario the slopes of the mountain, extending out to about 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) from the vent, may be exposed to pyroclastic flows sweeping down them, whilst much of the surrounding area could suffer from tephra falls. Because of prevailing winds, towns to the south and east of the volcano are most at risk from this, and it is assumed that tephra accumulation exceeding 100 kg/m² – at which point people are at risk from collapsing roofs – may extend out as far as Avellino to the east or Salerno to the south east. Towards Naples, to the north west, this tephra fall hazard is assumed to extend barely past the slopes of the volcano. The specific areas actually affected by the ash cloud will depend upon the particular circumstances surrounding the eruption.

The plan assumes between two weeks and 20 days' notice of an eruption and foresees the emergency evacuation of 600,000 people, almost entirely comprising all those living in the zona rossa ("red zone"), i.e. at greatest risk from pyroclastic flows. The evacuation, by trains, ferries, cars, and buses is planned to take about seven days, and the evacuees will mostly be sent to other parts of the country rather than to safe areas in the local Campania region, and may have to stay away for several months. However the dilemma that would face those implementing the plan is when to start this massive evacuation, since if it is left too late then thousands could be killed, while if it is started too early then the precursors of the eruption may turn out to have been a false alarm. In 1984, 40,000 people were evacuated from the

Campi Flegrei area, another volcanic complex near Naples, but no eruption occurred.

Ongoing efforts are being made by the government at various levels (especially of Regione

Campania) to reduce the population living in the red zone, by demolishing illegally

constructed buildings, establishing a national park around the upper flanks of the volcano to prevent the erection of further buildings[60] and by offering financial incentives to people for moving away.[61] One of the underlying goals is to reduce the time needed to evacuate the area, over the next 20 or 30 years, to two or three days.

The volcano is closely monitored by the Osservatorio Vesuvio in Naples with extensive networks of seismic and gravimetric stations, a combination of a GPS-based geodetic array and satellite-based synthetic aperture radar to measure ground movement, and by local surveys and chemical analyses of gases emitted from fumaroles. All of this is intended to track magma rising underneath the volcano. Currently no magma has been detected within 10 km of the surface, and so the volcano is classified by the Observatory as at a Basic or Green

Level.

2.15

Vesuvius today

Figure 15 The crater of Vesuvius in 2012

The area around Vesuvius was officially declared a national park on June 5, 1995. The summit of Vesuvius is open to visitors and there is a small network of paths around the mountain that are maintained by the park authorities on weekends.

There is access by road to within 200 metres (660 ft) of the summit (measured vertically), but thereafter access is on foot only. There is a spiral walkway around the mountain from the road to the crater.There is access by road to within 200 metres (660 ft) of the summit

(measured vertically), but thereafter access is on foot only. There is a spiral walkway around the mountain from the road to the crater.

LISAD

Figures 1

POMPEII

Figure 16 Illustrated reconstruction, from a CyArk/University of Ferrara research partnership, of how the Temple of Apollo may have looked before Mt. Vesuvius erupted.

Figure 17 The same location today.

Figure 18 A Map of Pompeii, featuring the main roads, the Cardo Maximus is in Red and the Decumani Maximi are in green and dark blue. The southwest corner features the main forum and is the oldest part of the town.

Figure 19 The Forum with Vesuvius in the distance

Figure 20 Portrait of the baker Terentius Neo with his wife found on the wall of a Pompeii house.

Figure 21 Amphitheatre of Pompeii