Professional Journal A

advertisement

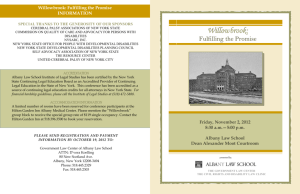

1 Special Education: From Institutions to Inclusion Erin Cataldo It was 1947 and there were children living in filthy, cramped quarters without adequate food and clothing. This place was called Willowbrook State School. Willowbrook was a facility for children with mental disabilities and was operated by the New York State Department of Mental Hygiene. The school was designed to provide services for 4000 children, but the population grew to over 6000. The institution’s purpose was to provide children with disabilities with food, shelter, clothing, and love. These are basic needs that could not be met by their families or the staff of the school. The families that still wanted to remain a small part of their children’s hopeless lives were allowed to visit on each Sunday. Some family members reported that they could hardly even move through the wards to get to their child’s room. There were children just lying all over the place. The facilities reeked with the scent of sweat, human urine, and feces. The children were dirty and very thin. Willowbrook’s proper name should not have included the word “school”. Robert F. Kennedy referred to Willowbrook as a “snake pit”. Due to lack of staff, basic hygiene and educational needs were not ever met. A meal and a bath, two things we take for granted, were sadly not guaranteed to the patients on a daily basis. The patients lacked social, emotional, and behavioral support and training, which led to unsafe and inappropriate interactions among the children and staff. Many of these children suffered injuries due to the lack of supervision by staff. The public became aware of the conditions, scandal, and abuses that were occurring at Willowbrook. In 1972, Geraldo Rivera, an investigative reporter, uncovered and reported on the 2 deplorable conditions at Willowbrook. The series of investigations brought to light the overcrowding, the lack of sanitary facilities, and the physical and sexual abuse of the residents by the members of the school staff. Because of this controversy, a class-action lawsuit was filed against the state of New York in March of 1972. It wasn’t until May of 1975 when a settlement was agreed upon in this case. The Willowbrook Consent Decree was signed to improve community placement for the “Willowbrook Class”. Due to the publicity that was generated by the case, the Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act (CRIPA) was signed in 1980. CRIPA was a federal law that was designed to protect the rights of people in institutions who had intellectual and developmental disabilities. This act allowed the department of justice to protect the rights of people who were in the care of state-operated institutions. The law wanted to ensure the safety of those individuals and to provide with them of an avenue to report issues of abuse. In 1983, the state of New York announced the closure of Willowbrook State School. By March of 1986, the number of children living at the newly-named Staten Island Developmental Center was reduced to 250 residents. Finally, the last child left the grounds on September 17, 1987. The closing of the institution required the Office of Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities to provide community placement options for the Willowbrook Class members.(Fisher,1996) Prior to the closing and the deinstitutionalization of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities, the Pennsylvania Association for Retarded Children (PARC) filed a lawsuit against the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The landmark decision in 1971 extended universal public educational laws to retarded children as a constitutional right. PARC argued that all mentally retarded children can benefit from an educational program. The law guaranteed 3 Free Public Education to all children from the ages 6 to 21. An agree was reached without an actual court hearing because the state admitted that it had violated the 14th amendment rights to due process by denying one segment of the population, retarded children, access to the education provided to the rest of the people. It agreed to place mentally retarded children in appropriate, free, public, education programs. A similar case was also filed against the District of Columbia Board of Education by Mills. Mills and PARC agreements were responsible for the passage of Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975. ("Encylopedia of american," 2011) Public Law 94-142 required every state and local school district who receives federal funds to find and educate at the public’s expense all handicapped children in its jurisdiction, regardless of the nature or severity of a child’s handicap. Although few states had good special education programs, many parents had to assume the financial responsibilities of private day school or institutional care because their handicapped cost more than public education could or would pay. With Public Law 94-192, Congress made it clear that public schools would educate handicapped children at public expense. Schools had spent billions of dollars under Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act to improve quality education for other minority children. With this law, Congress decided that we needed a national commitment to do the same thing for the most underserved minorities of all-handicapped children. For children 6 to 17, the law indicates that the state and local school districts must make reasonable efforts to locate handicapped children in the district and give priority to the most severely disabled. They were required to evaluate the learning needs of each child and develop and individualized education program (IEP) to meet those needs. They were required to place children in the least restrictive environment and had to evaluate the child’s progress and make 4 changes if needed. The final component allowed parents to challenge school decisions if they felt the services were not meeting their children’s needs.(Boyer,1979) The deinstitutionalization of children from state-operated facilities and the early Supreme Court cases for education were the building blocks for the community based and inclusionary services that are provided to children and families today. With the deinstitutionalization movement, residential and community rehabilitation services for young children and young adults were developed. The Department of Public Welfare through the Office of Mental Retardation Services provided funding to county MH/MR offices for residential support services to meet the needs of these children. The primary purpose of group homes was to provide a community residential setting to ensure that children and young adults were receiving assistance to achieve their maximum potential in the least restrictive environment. The range of services included teaching socialization skills, problem solving techniques, self-care skills, daily routine activities, and household and personal hygiene. It also promoted community involvement which included the use of public transportation, accessing medical services, using shopping centers, eating out in restaurants, and attending sporting and recreational activities. Following the community support movement, Pennsylvania started the “Person/Family Directed Support Waiver” in 1999. Most people with intellectual and developmental disabilities are eligible for Medical Assistance. Medical Assistance is a program that provides funding for health care services. The “Person/Family Directed Support Waiver” shifted the funding for children to live in group homes back to their families, so they can access the services they need at home. In keeping with the deinstitutionalization of children, Congress decided that states should shift their funding to provide resources at home instead of an institutional setting. 5 Congress gave states the flexibility to create their own programs of home and community-based services. In order to receive approval for a home and community-based waiver, a state must demonstrate that the waiver cannot be greater than the cost of institutional services. The menu of services for the consolidated waiver includes case management, residential programs, day habilitation, pre-vocational services, supported employment services, educational services, chore services, private duty nursing, specialized therapy, permanency planning for children and youth, respite care, environmental accessibility adaptations, and transportation. The P/FDS Wavier includes residential programs, day habilitation, pre-vocational services, supported employment services, chore services, respite cares, environmental accessibility adaptations, transportation, expanded therapy services, adaptive appliances, visual/ mobility therapy, behavior therapy, and visiting nurse. ("Disability adovacy support," 2012) The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is a United States federal law that oversees how the states and public schools provide early intervention, special education, and related services to children with disabilities. IDEA first came into being in the year 1990. IDEA only applies to states and educational agencies that accept educational funding under the IDEA. IDEA was originally created by Congress in 1975 to ensure that children with disabilities have the right to a free, appropriate, public education. IDEA has been amended a number of times with the most recent one being in December of 2004. IDEA 2004 clarifies the intended outcome for each child with a disability. Students must be provided a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) that prepares them for further education, employment, and independent living. Special Education and related services have to meet the unique learning needs of all eligible children with disabilities from preschool through age 21. 6 Children with disabilities who qualify for special education are automatically protected by Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and under the guidelines of Americans with Disabilites Act. The changes to IDEA in 2004 were to align with the requirements of the No Child Left Behind Act. (NCLB) NCLB allows financial incentives to states who improve their special education services for all students. ("Idea: The individuals," 2012) The Gaskin v. PDE Settlement was filed on June 30, 1994. The Gaskin family filed the lawsuit on behalf of school-aged students with disabilities who have been denied a FAPE in regular education classes with individual supportive services, or those who have been placed in these classrooms with supportive services which they require to be successful in the regular education classroom setting. The goal of these changes was that local school districts increase their capacity to provide supplementary services in regular education classrooms that students with disabilities need to receive a meaningful benefit. This settlement further enhances the policies and laws which are already in existence. (Grossman, 2005) We have come a long way from the halls of Willowbrook. Deinstitutionalization remains the goal of many states and policy makers continue to facilitate the closures of state-operated institutions, so that they can meet the needs of people with intellectual, developmental, and other physical disabilities in a community-based setting. Parents now have safeguards in place to protect the rights of their children with disabilities and to ensure that all children, regardless of their disability receive a Free Appropriate Public Education. Unlike the procedures that were in place at Willowbrook, parents now have the opportunity to review their full educational records, to participate in team meetings, and to be completely involved in placement decisions. Parents are now equal partners on the IEP team along with teachers, staff, and school personnel. They 7 have a right to request mediation or due process and to file complaints with the state system if they feel their rights or the rights of their child have been violated. Parents didn’t have the same opportunity and knowledge to protect their children when they were placed in state-operated instiutions. 8 Works Cited Fisher, J. (Director) (1996). Unforgotten: 25 years after willowbrook [DVD]. Encylopedia of american education. (2011, September 21). Retrieved from http://americaneducation.org/1511-pennsylvania-association-for-retarded-children-v-commonwealth-ofpennsylvania-parc-decision.html Boyer, E. (1979). Public law 94-142: A promising start?.Educational leadership, 298-301. Disability adovacy support hub. (2012). Retrieved from http://dash.drnpa.org/file/mr-waiver.pdf Idea: The individuals with disabilities education act. (2012, April). Retrieved from http://nichcy.org/laws/idea Grossman, E. (2005, June 25). Special education lawsuit settlement in pennsylvania brings hope to parents. The morning call, p. 1.