Read the Article - Bonnie Glass

advertisement

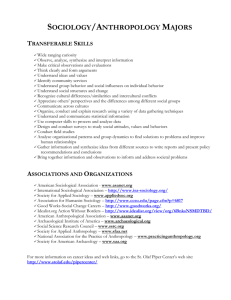

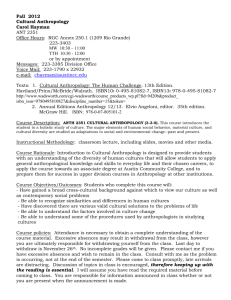

Ritual, Transformational Learning, and the Language of Emotion in an Anthropology Classroom© Bonnie Glass-Coffin, PhD/Utah State University bonnie.glasscoffin@usu.edu Presented at the AAC&U “Big Questions Breakfast” Atlanta, GA, Jan 2013 (Draft: Please Do Not Cite Without Written Permission from the Author) Introduction: Last spring I taught a class at my public, land-grant university that was, to put it mildly, unusual. “Introduction to Shamanism: Shamanic Healing for Personal and Planetary Transformation” was its title. In it, students were presented the “toolkit” of the shaman in order to access domains dismissed by most college professors as either “illusory” or “not-ourbusiness.” They were encouraged to dream and cry and laugh and explore. They were given license to feel in ways that continue to give many university administrators pause. You see, in university settings, a common assertion is that “emotions do not belong in the classroom, which should be reserved for teaching the facts and developing the cognitive skills to assess them” (Palmer and Zajonc, 2010:40). “I am not a therapist so don’t ask me to act like one,” decry faculty who are reticent to engage strong emotions in their students (Palmer and Zajonc, 2010:40). But, according to Parker Palmer and Arthur Zajonc, faculty who keep the tissue box firmly locked in the closet ignore more than 50 years of research about “the importance of attending to the emotions if we want to liberate the mind.” They do so to the peril of all learners—teachers and students alike. Engaging emotions in the classroom creates a space for shared humanity while creating a sense of relationship and of community. This turns teachers and students into passionate co1 participants where the relationships and experiences that have moved us most are not dismissed as irrelevant but are seen, instead as primary dimensions of our humanity while “giv[ing] meaning and provid[ing] explanation for our lives” (Lupton 1998:6). This kind of integrative education—that which serves the whole student—is gaining support in academe these days because it better meets student demands for classes that allow them to really wrestle with the “big questions” of their lives (Astin, Astin and Lindholm, 2011; Connor, 2007; Chang and Boyd, 2011; Palmer and Zajonc, 2010). These are questions like: “Why am I alive? Why do people suffer? How (or should) I serve others? And, what is the point, anyway?” Cognitive consideration of the “facts” alone does not prepare students for the challenges they face as they deal with the fallout of the “modern world” they have inherited. This world is one that has been built from the assumption that humans act autonomously upon an inanimate world rather than in relationship with an animated one. This assumption has had heartwrenching consequences that students feel as well as see. Integrative education makes a different assumption. It emphasizes Compassionate Action in an Interconnected World. It is about “inner-exploration” and about recognizing, building, and honoring relationships more than it is about just learning facts. It is about respecting difference and finding common ground. It is about co-participating and facing problems together. It is about anthropology at its core. In “pitching” this experiential pedagogy, I was emboldened by the findings of research with more than 130,000 students at more than 300 universities. What these studies found is that students yearn for opportunities to explore interpersonal as well as transpersonal interactions. They long to connect to one another as well as to that which lies “beyond” the veil that separates 2 worlds (Astin, Astin and Lindholm, 2010). I had already received tenure and had been promoted to the rank of full professor. I had won national awards for my teaching. So, I was pretty sure my Dean would give me this opportunity—even if he might discourage a younger colleague from making this leap. The “Experiment”: The intent of the class was to allow students the opportunity to access non-ordinary states of consciousness as a kind of opening to inner exploration through a quieting of the ego-mind. The idea was that, by accessing these non-ordinary states through meditation, shamanic journeying and other tried and true shamanic tools, students might begin to find some answers to life’s big questions within themselves. It was hoped that, along the way, they might share these insights in ways that would help others. We would explore together the value of connection for making sense of their individual lives. A trusting learning community was anticipated. It was integrative education at its best. It was also an emotional adventure. As I began teaching the class, a debate ensued about whether or not what I was asking to do violated a mandate that is taken very seriously in largely Mormon Utah. This is the prohibition about teaching religion in the public classroom. After multiple discussions with administrators and concerned faculty, the provisional consensus was that, as long as I was focusing on teaching a “method” rather than a “doctrine,” I could engage the students in a onesemester experiment to see if an experiential pedagogy might provide the means for students to more deeply engage these “big questions” in their lives. Because the course would involve building individual altars and sitting on the ground in a circle, the “standard” classroom I was given would have to be re-configured. Instead of 3 accommodating 40 students with lecture-style seating, the classroom would only hold 20 participants. I hoped for a projected enrollment of between 18-20 students to best accommodate the intense personal interactions and need for a flexible agenda that I anticipated. When I got the course list, however, I found the class to be seriously overenrolled. So, on the first meeting, in an attempt to reduce numbers, I told students they would be required to sign a waiver that warned of the possibility of complete “psychic-dismemberment” as a consequence of their participation. If they weren’t ready to seriously engage the consequences of deep transformation, I told them they should not take the course. Only two students dropped. I decided to open a second section of the course. Concerned about how to evaluate a course where inner exploration and personal transformation were primary learning objectives, I gave students two options for enrollment. They could take the course “Pass/Fail” and simply show-up to all required sessions during the 15 week term in order to receive course credit with a “pass.” If they chose to receive a grade, though, they were required to write weekly reflection papers about their experiences as well as to complete an academic research paper which compared these with published studies of shamanism, including its symbols and functions in particular cultural contexts. About half of the students opted for this option. The 15 class sessions each lasted approximately three hours. Each period was organized around themes. During the first week, students were introduced to the ritual process as a means for facilitating personal transformation. They learned the symbolism associated with the particular style of Peruvian healing altar they were asked to build—how the directions were associated with symbols of physical, emotional, spiritual and mental well-being that could be transacted and transformed as each student embodied the objects placed upon their altars with 4 corresponding experiences in their own lives. They learned how shamanic voyages of discovery called “soul-journeys” can be used to access teachings that come from “unseen” dimensions of life—teachings from “beyond the veil.” They learned how to “tap-in” to internal states where their stories of personal wounding and fear could be seen for what they were—as just stories they had been told and had told themselves, rather than intrinsic states of Being. And more than just “learning” about all these things, they practiced doing them. Along the way, the students learned how to share their insights with other students in a space of safety and acceptance, without crosstalk or self-recrimination. In each class period, students were introduced to various techniques for quieting the ego mind including meditation, breath-work, chanting and repetitive vocalization, and percussive/repetitive sound. Ritualized performance accompanied by introduction of sound, scent, guided imagery and focused intention was used to facilitate their inquiry. Afterwards, students were encouraged to “free-write” about insights obtained as well as to pay attention to their dreams and to keep a journal between class meetings. About every other week, we passed around a “talking stick” and students were invited to share their experiences. Sometimes, this process went quickly and sometimes not. Always, the experiences students chose to share became teaching moments for all gathered. In writing about one of these sharing sessions, a student commented that: Last week’s experience was amazing as I felt a connection with everyone as they shared their issues in what was going in their life. I realized from this experience just how much empathy I had for everyone and not just myself. The feeling of trust was very strong and I had a feeling of being in a community, 5 which is a feeling I have not felt in a very long time. I think part of this is my fault and I want to really rectify that so that I know there are people on which I can depend on and trust. The atmosphere was as if everyone knew everyone else so well and could relate in a way to what everyone was feeling when the feather was passed around. The atmosphere was very loving. Student evaluations of the course included statements that they valued “the many lessons I learned that will help me get through life,” the “new spiritual resources, skills, tools, and understandings” gained, the opportunity for “personal transformation” and the sense of “sacred community” that was built along the way. Students commented that they felt “safe,” “connected” and “healed.” The course was described as “life-changing” by many of the students who engaged in this experience. As one student in the class summarized it, “In this class, so many of us have shared from our hearts, experienced small and not so small miracles of growth, understanding, connection, joy, sorrow, recognition, compassion, peace, ever so many aspects of our physical and emotional experiences from our lives.” Student evaluations of course content (on a 6 point scale) averaged 5.75 (for course content) and 5.9 (for the teacher). Two students of the 38 who participated in the course evaluations chose to make their comments public. As Mark Wardle, a senior in anthropology commented, This course helped me gain an experiential understanding of the power in giving ideas form through ritual. Utilizing our inner energies, desires, and imaginations to project healing into the world must be the first step in bringing humanity back into balance and reciprocity with the Mother… And Kayla Aiken, a junior English/Asian Studies major commented, 6 Shamanism was a beautiful experience that opened my mind to the systematic harmony of the universe. I’ve never learned so much about myself. The meditation practices changed my life in ways my mind can’t even comprehend. Before this experience, I thought that the world was out to get me. Now I know that whatever I desire, the universe conspires in helping me to achieve it. I used to gaze down at the ground, but now I’m noticing the beauty of the world around me. This experience opened my mind more than I ever thought possible. I wish that everyone could experience…[this] to enter into the realm of self-awareness, connection, and spirituality. Discussion As much of the recent scholarship on emotions in anthropology suggests, taking the study of emotions seriously is about being willing to blur boundaries. It is about shifting our research from a focus on objectivity and observation to inter-subjectivity and passionate participation. It is about shifting the locus of inquiry from that of the omniscient observer to the relationship between co-committed inter-actors. It is, thus, about shifting from a focus on structure to a focus on emergence. It is about giving up control as a researcher and being willing to dive-deep, to feel passionately, and to be changed by the experiences of our research. It is scary to do this work as researchers—and as teachers. The need for me to “give up control” was certainly true. Passing the talking-stick around the room as part of our “council process” meant that students could share anything on their hearts in a space where they were made to feel safe and valued. During the course of the semester, students shared stories of abuse, of loneliness and disconnection, of loss and dissociation. Some shared experiences that made me cringe. I repeatedly insisted that what was shared in this space 7 of sacred connection with one another must remain confidential, but I often found it difficult to let go of my own worries as I considered what consequences I might face if word got out. My mantra was that every student’s opinions mattered and that all perspectives would be entertained—as long as they were offered without violating other student’s rights to their own experiences and beliefs. Many of my students were Mormon and framed their experiences in terms of their own religious persuasions. One student, who was a fundamentalist Christian, finally admitted on the last day of class that his entire reason for being in the course had been to “do the work of Jesus” and to be an available counselor to lead students back to Salvation after their spiritual dalliances with the Devil. At times during the semester, I wondered if the diversity of religious perspectives within the classroom might cause the experiment to simply implode. And then there was my own discomfort leading students in exercises that took me far beyond my own academic comfort zone. Yet, students stayed. They showed respect. They empathized. As we struggled, together, with the psychic dismemberment I had warned them about, students began also to share stories of connection and compassion, of mystical illumination and pure joy. On multiple occasions tears were shed, by students and instructor alike. The unexpected became ordinary as students shared their hearts. On one occasion, I asked students to stand in two circles, facing one another and looking deep into one another’s eyes, while I read a meditation about the different stories and symbolism associated with Sun and Moon—astral Father and astral Mother—in multiple cultures around the world. Many of the students responded, after that exercise, that it was the first time they had ever looked deeply into someone else’s eyes. One student commented on that experience by saying, 8 for a small space of time that felt almost eternal, [we] look[ed] deeply into the eyes of our classmates… In some I saw the shadows of lives past, great sorrows and pain, joy and love; in one I saw the most beautiful non-human, alien eyes, full of knowing and unknowing, [that were] looking back at me. I wondered, did he KNOW that he was alien here? What was his journey for? Is he on the Quest I sense that I am on, from another dimension, maybe even another time? What is he searching for? The power and strength in those not-human…eyes… poured back at me, leaving me touched to my soul and sparked recognition within that is still not fully understood or come to fruition. For some instructors, especially those untenured faculty colleagues at my institution, I know that opening this space for exploration would have been too challenging to consider. Yet, because of my own experiences as a researcher of shamanism who has been transformed by my work, I was drawn to this experiment in teaching with a passion I can scarcely contain. If, as a discipline, anthropology wants to have continued relevance in the world, it is my assertion that we must be willing to take these kinds of risks and open up our classrooms to the reality of our relatedness in the world. This is a reality that rests on emotion and ritual coparticipation, and on un-knowing. As one anthropology major who enrolled in my course commented early in the semester, There is wisdom that can be gained, and that which our education system lacks, by not only observing but participating in ritual saturated with symbolism and meaning. Our culture can discern meaning from words, but can we easily see what the placement of objects, the organization of chaos, and even our own movements and that of others can mean in the allegorical ritual of our daily lives? 9 Speaking as an American I think that we have a lot to learn from those who some think of as primitive for their lack of education but who in actuality are infinitely wiser than [we are.] Conclusion: I believe that opening a space for this kind of teaching and learning is what is most needed to make anthropology more relevant to a 21st Century world. Beyond decolonizing discourses, these adventures in expanded notions of sentience, of affect, and of relationship may, at the very least, give us hope as economies crumble and as human action becomes more environmentally unsustainable. These adventures in emotional engagement may return us to an that Martin Buber described as “I-Thou” rather than as “I-It. As one student summarized it during a recent discussion of our college-wide study group, “these kinds of courses are important because they make me feel like, at last, I am not an Object.” This seems a compelling reason to continue to embrace the emotional in our scholarship, in our classrooms, and in our definition of anthropology as a contributing force for good as we all tumble together towards a more humane existence in this 21st Century world. Bibliography: Astin, Alexander, Helen Astin and Jennifer Lindholm (2010). Cultivating the Spirit: How College Can Enhance Students’ Inner Lives. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Beatty, Andrew (2005). “Emotions in the Field: What Are We Talking About?” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 11:17-37. Chang, Heewon and Drick Boyd (2011). Spirituality in Higher Education: Autoethnographies. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press. 10 Connor, Robert (2007) “The Right Time for the Big Questions,” The Chronicle Review 52:40, B8 Glass-Coffin, Bonnie, (in press). “Belief is not Experience: The role of Personal Transformation as a Tool for Bridging Ontological Divides in Research and Reporting,” International Journal of Transpersonal Psychology. Glass-Coffin, B. (2009).Balancing on interpretive fences or leaping into the void: Reconciling myself with Castaneda and the teachings of don Juan. In B. Hearne & R. S. Trites (Eds.). A Narrative Compass: Stories that Guide Women’s Lives. (pp. 57-67). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. Glass-Coffin, B. (2010). Anthropology, shamanism and alternate ways of knowing-Being in the world: One anthropologist’s journey of transformation and discovery. Anthropology and Humanism, 35(2), 204-217. Glass-Coffin, B and Kiiskeentum (2012). “Ontological Relativism or Ontological Relevance: An Essay in Honor of Michael Harner,” Anthropology of Consciousness, 22(2): 113-126). Harner, Michael (1980). The Way of the Shaman. New York: Harper and Row. Krathwohl, Bloom and Masia (1964) Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Affective Domain. Leavitt, J. (1996) “Meaning and Feeling in the Anthropology of Emotions,” American Ethnologist, 23:3, 514-539. 11 Lindholm, Jennifer A., Melissa L. Millora, Leslie M. Schwartz, and Hanna Song Spinosa (2011). A Guidebook of Promising Practices: Facilitating College Students’ Spiritual Development, Berkeley: University of California Press. Lutz, Catherine and Geoffrey White (1986) “The Anthropology of Emotions,” Annual Review of Anthropology 15:405-436. Lupton, D (1998). The Emotional Self: A Sociocultural Exploration. London: Sage. Milton, Kay (2005) “Emotion (or Life or Universe or Everything),” Australian Journal of Anthropology 16:2, 198-211. Olsen, Carol Beth (2007). “The Role of Affect in Learning,” excerpted from The Reading, Writing Connection: Strategies for Learning in the Secondary Classroom,” Allyn and Bacon. On- line article: http://www.education.com/reference/article/role-affect-learning/. Accessed 10/12/2012. Palmer, Parker J. and Arthur Zajonc (2010). The Heart of Higher Education: A Call to Renewal/Transforming the Academy through Collegial Conversations. Walnut Creek: Jossey-Bass. Rockenbach, Alyssa Bryant and Matthew J. Mayhew, eds. (2013). Spirituality in College Students’ Lives: Translating Research into Practice. New York: Routledge. Thien, Deborah (2005) “After or beyond feeling: A Consideration of affect and emotion in geography,” Area, 37:4, 450-456. Wilce, James M. (2004) “Passionate Scholarship: Recent Anthropologies of Emotion,” Reviews in Anthropology 33:1-17. 12