Labour Relations (Tucker) - 2011-12 (1)

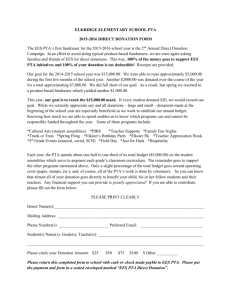

advertisement