Plant species covered by new eu regulations

advertisement

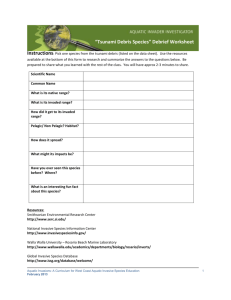

PLANT SPECIES COVERED BY NEW EU REGULATIONS A new regulation from the EU, to be finally agreed on 4th December, could place stringent controls on 37 non-native invasive species from 1st January 2016. These are species that have been assessed as posing such a high risk of invasion within one or more EU member states that a co-ordinated, Europe-wide response is needed to limit their spread. It will become an offence to keep, cultivate, breed, transport, sell or exchange these species, or release them, intentionally or unintentionally, into the environment anywhere within the EU. There will be no attempt to remove species listed on the EU Regulation from peoples’ gardens, so long as they are acting responsibly and not encouraging them to spread, e.g. by following appropriate codes of conduct. However, sites in the wild where these invasive species are causing problems should be restored and costs may be recovered in accordance with the ‘polluter pays’ principle, meaning that whoever caused them to spread or be released into the wild may have to foot the bill for subsequent control. There are 14 plant species on the list. The following gives some background information about each one, assess the invasive situation in the UK and gives recommendations on how we should deal with them in the wild and what to do if you have them in your garden. We’ve arranged the plants in four groups below reflecting their availability, popularity and invasive potential in the UK. 1. POPULAR GARDEN PLANTS American skunk-cabbage (Lysichiton americanus) What is it? A huge, imposing perennial producing paddle-shaped leaves up to 1.5 metres tall and yellow arum-like flowers in spring that are spectacular but foul-smelling (hence the name). It comes originally from western North America and is very widely available from garden centres and nurseries for planting besides ponds, on stream sides and in bog gardens. It spreads vigorously in wet woodland, wetlands and ditches, forming dense stands that out-compete native vegetation by shading and smothering. Reproduction by seed in the wild is frequent. It has now been reported from at least 10 EU countries. © GBNNSS In the UK? This species has been grown in British gardens since at least 1901 and is very popular, especially in larger gardens with lakes, ponds and rivers. Although it’s been known in the wild since 1905, it’s being reported with increasing frequency; occurrences in the wild have increased by 84% in 15 years and it’s now recorded from 365 10-km squares throughout Britain and Ireland. We are hearing of large colonies being found in wet alder woodland and willow carr, on swamps and marshes and in ditches, forming dense colonies that out-compete native vegetation. It spreads by underground rhizomes and by seed, which can be carried hundreds of metres away in water to establish new colonies. Sites are appearing at all altitudes, from near sea level to over 250 meters in the Snowdonia and Cairngorms mountains. Large infestations are proving difficult to control; in the New Forest , for example, it has now become dominant in some wet alder woodlands near Minstead and on the River Lymington, leading to nearly 100% eradication of native woodland ground flora (such as bluebell, wood anemone and sanicle) in some sites. Total cost of control at seven New Forest sites has been £9,157 since 2010 and eradication work is expected to last until at least 2020. What should we do about it? The rapid spread and invasive behaviour of this species is causing increasing alarm and populations in the wild should be controlled with some urgency, especially in areas that are botanically important and rich in wildlife, such as the New Forest Important Plant Area (IPA). Monitoring should be stepped up to detect new sites and newly-established populations should be controlled before they become a problem. Our advice? Avoid growing this species in your garden (it can quickly overrun small areas), especially if it could spread to neighbouring rivers, woodlands or wetland areas. It can be controlled by the targeted use of systemic herbicides, which are easy to apply to the large leaves, or dig plants out and dry thoroughly before composing. There are several good alternatives to grow instead; Asian Skunk-cabbage (Lysichiton camtschatcensis) is a slightly smaller, less invasive species with beautiful white flowers, or try the cream-flowered hybrid between the American and Asian species which is reported to be sterile and therefore cannot spread to new sites. Curly waterweed (Lagarosiphon major) What is it? An aquatic plant from south Africa commonly sold as an oxygenator for ponds and aquaria. It remains submerged underwater, producing long, branching stems that are densely clothed with dark green pointed leaves that curl sharply back towards the main stem. © RPS Group PLC The stems float just under the surface of the water, producing dense mats up to 3 metres thick. The smallest of stem fragments can grow into new colonies, assisting its spread to new sites via accidental contamination by boats, machines, clothing or animals. It can grow to dominate entire ponds and it also occurs in lakes, canals and flooded mine workings and gravel pits. Its main impact is through blocking light to other plants – the dense floating mats shade everything below them – and it has been shown to displace and out-compete native aquatic plants such as pondweeds and water-milfoil, as well as invertebrates. It also alters the chemical composition of the water, making it more acidic and therefore reducing the photosynthetic ability of other species. Control is difficult as herbicides cannot be used freely in many water bodies and their use is increasingly restricted. Mechanical removal often leads to huge numbers of small stem fragments that can establish new plants. It is widely naturalised in W. Europe (11 countries) and is a serious invasive problem in New Zealand. In GB and Ireland? This species is a very popular garden plant, sold at many garden centres and nurseries. It was first recorded naturalised in the wild in Britain in 1944 and has now been recorded from 645 10-km squares, mainly in southern England, south Wales and N.W. England. Many introductions appear to arise from intentional plantings or throw-outs from ponds and aquariums. It does considerable damage, both ecologically and economically. Lough Corrib, for example, is the 2nd largest lake in Ireland and is important for its salmon and trout fishing. First found in 2005, Curly Waterweed now infests 160 bays in the lake, negatively affecting native fish, invertebrates and plants, and it’s estimated that it could eventually overgrow ca. 11,000 ha (61% of the area) of the lake. Following extensive trials to establish the best methods of control, eradication began in 2006 and the infected area has now been reduced from 100ha to 10ha, with the cost of the total project (including the trails) totalling over €1.5 million (£1.06 million). What should we do about it? Since this species is already widespread in the wild in Britain, eradication should focus on sites and areas that are important for wildlife, especially Important Plant Areas (IPAs) with freshwater interest such as the Dunkeld-Blairgowrie Lochs IPA and the Peterborough Brick Pits IPA. Implementation of existing voluntary codes to reduce infection of aquatic sites (e.g. Be Plant Wise) and prevent release of garden material into the wild (e.g. Horticultural Code of Practice for England & Wales and Scotland) are also essential to reduce further spread. Our advice? Don’t grow this plant in your pond! If you have it, control is probably best achieved by carefully hand pulling as much material as possible. Small fragments will re-grow so careful control will probably be needed for a few years. Alternatively, remove the plants and livestock you want to keep and cover the pond in very thick black plastic (to exclude light) for 6 months. This species should never really have been sold – it has little horticultural value and is bad news for garden ponds. There are very good alternative native oxygenating plants such as Rigid Hornwort (Ceratophyllum demersum), Curly Pondweed (Potamogeton crispus) and Spiked Water-milfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum). Carolina water-shield (Cabomba caroliniana) What is it? An aquatic plant from subtropical temperate areas of eastern N. America and southern S. America. Its long stems are clothed in very attractive feathery leaves and it occasionally produces white flowers above the water. It occurs in the still or slow-flowing waters of lakes, ponds, ditches and canals and growth rates of up to 5cm a day have been reported. It produces seed but spreads mainly through its brittle stems breaking into fragments and growing into new plants. It grows very densely, impacting native vegetation, © RPS Group PLC water quality and fishing. It has been reported widely as an invasive species (including Asia, Australasia and N and S America) and is naturalised in six EU countries. In the UK? This is one of the most popular aquatic plants for tropical fish tanks as it grows easily and quickly and is highly decorative. Coming from subtropical-temperate areas it is only marginally hardy in Britain – it grows best between 13-27OC and therefore cannot survive outside under normal conditions – normal winters would kill it off. However, was discovered in 1969 growing happily in a section of the Forth & Clyde Canal that received heated water from a nearby factory. However, it was discovered in an unheated section of the Basingstoke Canal in 1990; it is still there and is spreading at a rate described as “alarming”. This indicates this species could become established more frequently, especially in a warming climate. What should we do about it? This is a good example of “nipping a problem in the bud”, putting control measures in place at the very earliest stages of invasion. This is much more effective and cheaper than tackling species once they’ve become well established. Control of this species in the Basingstoke Canal should be a priority now before it spreads too far, and adequate monitoring should be in place to detect new sites. Existing biosecurity measures to prevent the spread of aquatic plants (e.g. Be Plant Wise) should be implemented. Our advice? If you grow this plant in your fish tank, do all that you can to keep it there! Do not allow it to get out into any ponds or waterways, especially in warm urban areas. In tropical fish tanks it grows rapidly and needs cutting back frequently, so make sure you dry out cut material thoroughly before composting. It’s better to grow alternative species, such as the tropical Red Cabomba (Cabomba furcata) – which cannot survive outside in Britain - or our native Hornwort (Ceratophyllum demersum). Water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) What is it? A remarkable floating aquatic plant from the Amazon basin which produces rosettes of floating leaves, each with a swollen, air-filled stalk and spikes of attractive blue flowers in summer. In tropical and sub-tropical climates it spreads with remarkable speed on lakes, reservoirs and slow-moving rives to form vast, dense floating mats. It’s widely regarded as the world’s most troublesome invasive plant in frost-free areas, being reported from 133 countries and causing severe biological, economical and social impacts in many of these. In Europe, it is reported from 8 countries, but is not currently regarded as invasive in any of these. It could become a problem in southern Europe if climate warming continues. In the UK? This species is popular in gardens, being widely sold in garden centres and nurseries, especially during early summer. Because it’s not hardy here, it’s almost treated like a summer bedding plant for ponds. In the wild, it’s been recorded from about 36 sites in total, mostly during the period 2000-2009, but almost all of these are transient and don’t survive the winter. The optimum temperature for growth is 25-30°C, although short periods at freezing can sometimes be tolerated. There is one case where plants appear to have survived the very mild winter of 1989/1999 in a ditch in north London. If Great Britain is ever warm enough for this species to become a problem we’ll have plenty of other things to worry about! What should we do about it? The European ban will see an end to trade in this species, even though it actually poses very little threat to our native flora at the moment. It’s likely that the small trickle of transient occurrences in the wild will cease. Our advice? Try growing some of our native floating aquatic plants such as Frogbit (Hydrocharis morsus-ranae) or Water-soldier (Stratiotes aloides). Alternatively, Water-lettuce (Pistia stratiotes) is another tropical floating aquatic that cannot survive outside in Great Britain. 2. SPECIES ALREADY BANNED FROM SALE IN UK Three aquatic species on the EU list have already been banned from sale in Great Britain following legislation introduced in April 2014. The impact they have had on our ponds, lakes and rivers is considerable and new infestations of the species below trigger a rapid response by agencies to eradicate them from sites. The new EU legislation strengthens the case to control the spread of these species in the wild. For additional information, please follow the links provided. Water primrose (Ludwigia grandiflora and Ludwigia peploides) This is probably the best example of a plant who’s spread in the wild has been “nipped in the bud” by a ban on sale before it became too widespread. First recorded in the wild in © Trevor Renals Britain as recently as 1999, this South and Central American species has now been found growing at about 19 sites and is proving to be stubborn and almost impossible to eradicate at some. Repeated herbicide control from 2009-2012 at Breamore Marsh SSSI (Hampshire), a site for Great Crested Newt and Brown Galingale, had no effect, so the entire pond was excavated in 2013 and the infected material buried in a nearby site and capped to prevent further spread. Floating pennywort (Hydrocotyle ranunculoides) First recorded in the wild in Britain in 1990 and widely sold for gardens and aquariums, this species – originally from North America - is now recorded from 163 10-km squares in the wild, showing how quickly these invasive species can spread when introduced through horticulture. It grows very rapidly, forming © GBNNSS floating blankets that exclude light and clog water channels. Control is expensive and time-consuming. It appeared on the River Soar around Leicester in 2004 and spread quickly. Despite years of hand pulling by volunteers and herbicide application complete eradication appears to be impossible; £20,000 was spent on control measures in 2014. Parrot's-feather (Myriophyllum aquaticum) More widely established in the wild than Water Primrose and Floating Pennywort (it’s been recorded in over 480 10-km squares, mostly in southern England) and therefore much more of a challenge to control, this rampant aquatic rapidly over-runs ponds, ditches, canals and reservoirs. At Shortwood Common Pond, one of the richest ponds in England for plant and insect life, the spread of Parrot’-feather has led to the loss of Brown Galingale, a very rare pond-side sedge. © GBNNSS 3. COOL-CLIMATE PLANTS THAT ARE VERY RARELY GROWN IN BRITAIN Tree groundsel (Baccharis halimifolia) What is it? A large shrub from eastern North America grown for its dense heads of small, daisy-like flowers. It grows in coastal situations from Connecticut south to Florida and the Bahamas, and is highly invasive in parts of Australia (especially sub-tropical areas), New Zealand and Europe (France, Spain and Italy), where it invades saltmarsh habitats. In the UK? This species is very rarely grown in gardens; just two suppliers are listed in the RHS Plant Finder. In the wild it has been recorded from just three sites; at the most famous of these, at Mudeford in Hampshire, it was planted beside a car park and has shown no sign of spreading since being found in 1924. What should we do about it? Given its invasive character abroad any UK populations should be monitored periodically. Control should be undertaken if there is evidence of spread. Our advice? Don’t grow this species, especially in coastal areas. There are plenty of excellent alternative native shrubs for coastal gardens, such as Holly (Ilex aquifolium), Shrubby Cinquefoil (Potentilla fruticosa) and Blackthorn (Prunus spinosa). Persian hogweed (Heracleum persicum) What is it? One of several large hogweeds, the ground seeds of this species are a popular flavouring (known as Golpar) in Persian cooking. The plant comes from cool, mountainous parts of Iran and, following its introduction in the 1830s, it has become invasive in parts of Norway. In the UK? This species has been found in the wild a few times, but only three sites have been reported in the last 15 years. It does not appear to be behaving invasively and it’s very rarely grown in Britain (it’s not listed in the RHS Plant Finder). What should we do about it? Some species of hogweed are highly invasive, so it’s important that we monitor the escape and spread of all non-native Heracleum in the wild. Since this species is invasive in Norway we should be alert for populations becoming established in areas with a similar climate here and control should be undertaken if there is evidence of spread. Our advice? Do not grow this species. Sosnowskyi's hogweed (Heracleum sosnowskyi) What is it? One of several species of giant hogweed, this species can reach a height of 5 metres. Originally native to the Caucasus, it is now an invasive weed in Eastern Europe, Poland and Russia. In the UK? This species has never been found in the wild in the UK. It’s very rarely grown in Britain (it was last listed in the RHS Plant Finder in 2010). What should we do about it? Although not currently a problem in the UK, some species of hogweed are highly invasive so it’s important that we monitor the escape and spread of all non-native Heracleum in the wild. Our advice? Do not grow this species. 4. WARMER-CLIMATE PLANTS NOT GROWN IN BRITAIN Parthenium weed (Parthenium hysterophorus) What is it? A highly invasive annual weed that rapidly colonises bare, disturbed soil. It’s a tropical species native to southern United States, Mexico and Central and South America, and has become a serious agricultural weed in many parts of the southern hemisphere. It can persist in areas where the average temperature is above 10oC; it has been reported from Poland and Belgium but only as transient occurrences that didn’t persist. In the UK? This species is not grown in the UK and has never been recorded in the wild. What should we do about it? Monitor any occurrences and spread in southern Europe. Our advice? Don’t grow this species. Mile-a-minute weed (Persicaria perfoliata / Polygonum perfoliatum) What is it? A fast-growing, herbaceous vine from Asia, rather like a bindweed, that scrambles up to a height of 6 meters and clothes other plants, shrubs and trees. Although native to tropical and sub-tropical areas, it has become established and invasive in parts of North America, from Virginia northwards to New York; it appears to be capable of surviving in areas where the average minimum temperature is above 0oC. It’s also known to be invasive in the warmer temperate parts of west Turkey. In the UK? Mile-a-Minute Weed (not to be confused with Mile-a-Minute Vine, Fallopia baldschuanica) is not grown in the UK and has never been recorded in the wild, but it’s tolerance of colder climates in North America mean it could become established here. What should we do about it? The ban on trade is very helpful, as it was first established in the USA following its introduction to a nursery site. It could potentially flourish in the warmer and wetter parts of the UK, so it’s one to keep out. Our advice? Don’t grow this species. Kudzu vine (Pueraria montana var. lobata) What is it? A tropical vine native to East Asia. This climbing bean has widely introduced to India, North and South America and Australasia, but has only become highly invasive in the warmer parts of North America where it was originally planted to prevent soil erosion. It’s been recorded growing 25cm a day and can smother building and telegraph poles as well as severely impacting native habitats. It has been recorded in the wild in Italy and Switzerland but is not regarded as invasive. In the UK? This species is not normally grown in the UK and has never been recorded in the wild. What should we do about it? Since Kuzdu vine needs average minimum temperatures above 0oC it could grow in warmer and wetter parts of the UK, but is unlikely to become invasive. Any new occurrences should be closely monitored. Our advice? Don’t grow this species.