Croup usually begins with nonspecific respiratory symptoms (ie

advertisement

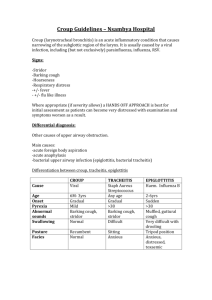

Stridor is an abnormal, high-pitched sound produced by turbulent airflow through a partially obstructed airway at the level of the supraglottis, glottis, subglottis, and/or trachea.[1] The tonal characteristics of the sound are extremely variable (ie, harsh, musical, or breathy); however, combined with the phase, volume, duration, rate of onset, and associated symptoms, the tonal characteristic may provide additional diagnostic clues. Stridor is a symptom, not a diagnosis or disease, and the underlying cause must be determined. Stridor may be inspiratory, expiratory, or biphasic depending on its timing in the respiratory cycle. Inspiratory stridor suggests a laryngeal obstruction, while expiratory stridor implies tracheobronchial obstruction. Biphasic stridor suggests a subglottic or glottic anomaly. In addition to a complete history and physical, as well as other possible additional studies, most cases require flexible and/or rigid endoscopy to adequately evaluate the etiology of stridor History The most common presenting symptom is loud, raspy, noisy breathing. The caretaker may interpret this symptom as wheezing or even as a severe upper respiratory tract infection. Depending on the underlying etiology, the presentation may be acute or chronic and may be accompanied by other symptoms. If symptoms are not observed in the office, especially when they are present only at night, having parents make a tape recording, preferably even videotaping, can provide useful information. A thorough history may provide helpful clues to the underlying etiology of stridor. Place particular emphasis on the age of onset, duration, severity, and progression of the stridor; precipitating events (eg, crying, feeding); positioning (eg, prone, supine, sitting); quality and nature of crying; presence of aphonia; and other associated symptoms (eg, paroxysms of cough, aspiration, difficulty feeding, drooling, sleep disordered breathing).[6] Perinatal history is especially important and should include direct questioning regarding maternal condylomata, type of delivery (including shoulder dystocia), endotracheal intubation use and duration, and presence of congenital anomalies. Past surgical history, particularly neck or cardiothoracic surgeries, puts the recurrent laryngeal nerve at risk of injury Obtain a detailed developmental history. In addition, elicit history of color change, cyanosis, respiratory effort, and apnea to determine the severity of stridor. A feeding and growth history should be evaluated because significant airway obstruction can lead to caloric waste, resulting in lack of weight gain and growth. Additionally, regurgitation and spitting up could be a sign of gastroesophageal reflux (GER) that can cause laryngeal and tracheal mucosal irritation that could lead to edema and stridor. Physical On initial presentation, especially in patients with acute onset of symptoms, immediately assess the child for severity of stridor and respiratory compromise. Give special attention to the heart and respiratory rates, cyanosis, use of accessory muscles of respiration, nasal flaring, level of consciousness, and responsiveness. If distress is moderate to severe, further physical examination should be deferred until the patient reaches a facility equipped for emergent management of the pediatric airway. Physical examination of a patient with suspected acute epiglottitis is contraindicated. The patient may prefer certain positions that alleviate the stridor. Note the presence of infection in the oral cavity; crepitations or masses in the soft tissues of the face, neck, or chest; and deviation of the trachea. Use care when examining (especially palpating) the oral cavity or pharynx because sudden dislodgement of a foreign body or rupture of an abscess can cause further airway compromise. Drooling from the mouth suggests poor handling of secretions. Observe the character of the cough, cry, and voice. The presence of fever and toxicity generally implies serious bacterial infections. Careful auscultation of the nose, oropharynx, neck, and chest helps to discern the location of the stridor. In infants, give special attention to craniofacial morphology, patency of the nares, and cutaneous hemangiomas. Growth parameters are very helpful, especially in evaluation of chronic stridor Causes Acute stridor Laryngotracheobronchitis, commonly known as croup, is the most common cause of acute stridor in children aged 6 months to 2 years. The patient has a barking cough that is worse at night and may have low-grade fever. Aspiration of foreign body is common in children aged 1-2 years. Usually, foreign bodies are food such as nuts, hot dogs, popcorn, and hard candy that is inhaled. A history of coughing and choking that precedes development of respiratory symptoms may be present. Bacterial tracheitis is relatively uncommon and mainly affects children younger than 3 years. It is a secondary infection (most commonly due to Staphylococcus aureus) following a viral process (commonly croup or influenza). Retropharyngeal abscess is a complication of bacterial pharyngitis observed in children younger than 6 years. The patient presents with abrupt onset of high fevers, difficulty swallowing, refusal to feed, sore throat, hyperextension of the neck, and respiratory distress. Peritonsillar abscess is an infection in the potential space between the superior constrictor muscles and the tonsil. It is common in adolescents and preadolescents. The patient develops severe throat pain, trismus, and trouble swallowing or speaking. Spasmodic croup, also termed acute spasmodic laryngitis, occurs most commonly in children aged 1-3 years. Presentation may be identical to croup. Allergic reaction (ie, anaphylaxis) occurs within 30 minutes of an adverse exposure. Hoarseness and inspiratory stridor may be accompanied by symptoms (eg, dysphagia, nasal congestion, itching eyes, sneezing, wheezing) that indicate the involvement of other organs. Epiglottitis is a medical emergency occurring most commonly in children aged 2-7 years. Clinically, the patient experiences an abrupt onset of high-grade fever, sore throat, dysphagia, and drooling. Chronic stridor Laryngomalacia is the most common cause of inspiratory stridor in the neonatal period and early infancy and accounts for up to 75% of all cases of stridor.Stridor may be exacerbated by crying or feeding. Placing the patient in a prone position with the head up improves the stridor; supine position worsens the stridor. Laryngomalacia is usually benign and self-limiting and improves as the child reaches age 1 year. If significant obstruction or lack of weight gain is present, surgical correction or supraglottoplasty may be considered if there are observed tight mucosal bands holding the epiglottis close to the true vocal cords or redundant mucosa overlying the arytenoids.] It should be kept in mind that the presentation of laryngomalacia in older children (late-onset laryngomalacia) can differ from that of congenital laryngomalacia.Possible manifestations of late-onset laryngomalacia include obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, exercise-induced stridor, and even dysphagia. Supraglottoplasty can be an effective treatment option. Patients with subglottic stenosis can present with inspiratory or biphasic stridor. Symptoms can be evident at any time during the first few years of life. If symptoms are not present in the neonatal period, this condition may be misdiagnosed as asthma. Congenital subglottic stenosis occurs when an incomplete canalization of the subglottis and cricoid rings causes a narrowing of the subglottic lumen. Acquired stenosis is most commonly caused by prolonged intubation (see articles on glottic and subglottic stenosis). Vocal cord dysfunction is likely the second most common cause of stridor in infants. Unilateral vocal cord paralysis can be congenital or secondary to birth or surgical trauma, such as cardiothoracic surgery. Patients with a unilateral vocal cord paralysis present with a weak cry and biphasic stridor that is louder when awake and improves when lying with the affected side down. Bilateral vocal cord paralysis is a more serious entity. Patients usually present with aphonia and a high-pitched biphasic stridor that may progress to severe respiratory distress. It is usually associated with CNS abnormalities, such as Arnold-Chiari malformation or increased intracranial pressure. Vocal cord paralysis in infants usually resolves within 24 months. Laryngeal dyskinesia, exercise-induced laryngomalacia, and paradoxical vocal cord motion are other neuromuscular disorders that may be considered. Laryngeal webs are caused by an incomplete recanalization of the laryngeal lumen during embryogenesis. Most (75%) are in the glottic area. Infants with laryngeal webs have a weak cry and biphasic stridor. Intervention is recommended in the setting of significant obstruction and includes cold knife or CO2 laser ablation. Laryngeal cysts are a less frequent cause of stridor. They are usually found in the supraglottic region in the epiglottic folds. Patients may present with stridor, hoarse voice, or aphonia. Cysts may cause obstruction of the airway lumen if they are very large. Laryngeal hemangiomas (glottic or subglottic) are rare, and half of them are accompanied by cutaneous hemangiomas in the head and neck. Patients usually present with inspiratory or biphasic stridor that may worsen as the hemangioma enlarges. Typically, hemangiomas present in the first 3-6 months of life during the proliferative phase and regress by age 12-18 months. Medical or surgical intervention is based on the severity of symptoms. Treatment options consist of oral steroids, intralesion steroids, laser therapy with CO2 or potassium-titanyl-phosphate (KTP) lasers, or surgical resection. Oral propranolol has been proven to be an effective medical treatment in the appropriate population (contraindicated in children with severe asthma, diabetes, or heart disease). Laryngeal papillomas occur secondary to vertical transmission of the human papilloma virus from maternal condylomata or infected vaginal cells to the pharynx or larynx of the infant during the birth process. These are primarily treated with surgical excision, with questionable use of cidofovir and interferon in refractory cases.[18] A high rate of recurrence of disease is noted, with a need for multiple surgical debridements and a small risk of malignancy (5% malignant degeneration). Tracheomalacia is the most common cause of expiratory stridor. It is caused by a defect on the cartilage resulting in the loss of rigidity necessary to maintain the tracheal lumen patent or by an extrinsic compression of the trachea. Tracheal stenosis can be congenital or secondary to extrinsic compression. Congenital stenosis is usually related to complete tracheal rings, is characterized by a persistent stridor, and requires surgery based on severity of symptoms. The most common extrinsic causes of stenosis include vascular rings, slings, and a double aortic arch that encircles the trachea and esophagus. Pulmonary artery slings are also associated with complete tracheal rings. External compression can also result in tracheomalacia. Patients usually present during the first year of life with noisy breathing, intercostal retractions, and a prolonged expiratory phase. Differential Diagnoses Congenital Arterial and Venous Anomalies: Surgical Perspective Congenital Stridor Gastroesophageal Reflux Laryngomalacia Subglottic Stenosis Tracheomalacia Laboratory Studies On initial evaluation, pulse oximetry may be useful to determine the extent and severity of the stridor and respiratory compromise. For moderate-to-severe cases, arterial blood gas may be needed. Other laboratory evaluations may be performed as dictated by the clinical situation. Generally, no investigations are required for mild stridor. Imaging Studies Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the neck and chest are useful to evaluate the airway and lungs. High-kilovoltage, short-exposure, endolateral airway radiographs (useful to demonstrate upper airway structures) or inspiratory and expiratory or lateral decubitus radiographs to demonstrate air trapping may be used to supplement AP and lateral radiographs. Barium esophagram may be performed if vascular compression, tracheoesophageal fistula, GER, or neurological dysfunction is suspected. Contrast-enhanced CT scanning can demonstrate mediastinal masses or aberrant vessels. An MRI may be helpful in delineating lesions of the upper airway and vascular anomalies. If GER is suspected, a pH probe or barium swallow may be performed to support the diagnosis. Other Tests Pulmonary function testing may be useful to differentiate restrictive and obstructive lung processes and to define whether the obstruction is in the upper or lower airway. Polysomnography may be required under certain circumstances, especially if history suggests obstructive sleep apnea. Procedures The key to defining stridor of all phases is to look at the airway. Direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy is the criterion standard for making a diagnosis in infants and children with stridor. In children with stable oxygen saturations and in whom findings on a lateral neck radiograph or the clinical picture does not indicate acute epiglottitis, the initial procedure to evaluate stridor should be a flexible laryngoscopy performed by an otolaryngologist in the clinic with topical vasoconstrictor and/or topical anesthetic as needed. The status of the larynx can be addressed, looking for abnormalities such as laryngomalacia, true vocal cord paresis or paralysis, laryngeal tumors or cysts, or signs and symptoms of GER. Often, a good evaluation is possible, or, occasionally, only a glimpse of the subglottis is observed, which may help direct further evaluation, such as a formal direct laryngoscopy and bronchoscopy in the operating room. Medical Care The treatment of stridor must be tailored according to the underlying or predisposing condition. Emergent management consists of ensuring that the airway is adequate. If not, appropriate resuscitative measures must be initiated. Some conditions (eg, epiglottitis, bacterial tracheitis) may require antibiotics, while steroids may be useful in other situations. Surgical Care Certain conditions, such as severe laryngomalacia, laryngeal stenosis, critical tracheal stenosis, laryngeal and tracheal tumors and lesions (eg, laryngeal papillomas, hemangiomas, others), and foreign body aspiration, require surgical correction. Occasionally, tracheotomy is used to protect the airway to bypass laryngeal abnormalities and stent or bypass tracheal abnormalities. Other conditions, such as retropharyngeal and peritonsillar abscess, may have to be dealt with on an emergent basis. Please see relevant articles for specific management Diet Patients with moderate to severe stridor should be given nothing by mouth (NPO) in preparation for possible intubation, laryngoscopy, bronchoscopy, and tracheotomy. croup History Croup usually begins with nonspecific respiratory symptoms (ie, rhinorrhea, sore throat, cough). Fever is generally low grade (3839°C) but can exceed 40°C. Within 1-2 days, the characteristic signs of hoarseness, barking cough, and inspiratory stridor develop, often suddenly, along with a variable degree of respiratory distress. Symptoms are perceived as worsening at night, with most ED visits occurring between 10 pm and 4 am. Symptoms typically resolve within 3-7 days but can last as long as 2 weeks. Spasmodic croup (recurrent croup) typically presents at night with the sudden onset of "croupy" cough and stridor. The child may have had mild upper respiratory complaints prior to this, but more often has behaved and appeared completely well prior to the onset of symptoms. Allergic factors may cause recurrent croup due to respiratory epithelial changes from the viral infection. Another diagnostic consideration is gastroesophageal reflux (GER). Studies of children presenting with recurrent croup have reported relief of their respiratory symptoms when treated for reflux.[13] . 2 Background Croup is a common, primarily pediatric viral respiratory tract illness. As its alternative names, laryngotracheitis and laryngotracheobronchitis, indicate, croup generally affects the larynx and trachea, although this illness may also extend to the bronchi. It is the most common etiology for hoarseness, cough, and onset of acute stridor in febrile children. Symptoms of coryza may be absent, mild, or marked. The vast majority of children with croup recover without consequences or sequelae; however, it can be life-threatening in young infants. Croup manifests as hoarseness, a seal-like barking cough, inspiratory stridor, and a variable degree of respiratory distress. However, morbidity is secondary to narrowing of the larynx and trachea below the level of the glottis (subglottic region) Child with croup. Note the steeple or pencil sign of the proximal trachea evident on this anteroposterior film. Courtesy of Dr. Kelly Marshall, CHOA at Scottish Rite. Young infants who present with stridor require a meticulous evaluation to determine the etiology and, most importantly, to exclude rare life-threatening causes. Although croup is usually a mild, self-limited disease, upper airway obstruction may result in respiratory distress and even death. Etiology Viruses causing acute infectious croup are spread through either direct inhalation from a cough and/or sneeze or by contamination of hands from contact with fomites, with subsequent touching the mucosa of the eyes, nose, and/or mouth. The most common viral etiologies are parainfluenza viruses. The type of parainfluenza (1, 2, and 3) causing outbreaks varies each year. The primary ports of entry are the nose and nasopharynx. The infection spreads and eventually involves the larynx and trachea. Although the lower respiratory tract may also be affected, some practitioners consider laryngotracheobronchitis a separate entity, with bacterial secondary infection as the potential cause.. Spasmodic croup (laryngismus stridulus) is a noninfectious variant of the disorder, with a clinical presentation similar to that of the acute disease but with less coryza. This type of croup always occurs at night and has the hallmark of reoccurring in children; hence it has also been called “recurrent croup.” In spasmodic croup, subglottic edema occurs without the inflammation typical in viral disease. Although viral illnesses may trigger this variant, the reaction may be of allergic etiology rather than a direct result of an infectious process. Causes Parainfluenza viruses (types 1, 2, 3) are responsible for as many as 80% of croup cases, with parainfluenza types 1 and 2, accounting for nearly 66% of cases. Type 3 parainfluenza virus causes bronchiolitis and pneumonia in young infants and children. Type 4, with subtypes 4A and 4B, are not as well understood and tend to be associated with milder clinical illness. Influenza A is associated with severe respiratory disease as it has been detected in children with marked respiratory compromise. The bacterial pathogen, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, has also been identified in a few cases of croup.[5] Prior to 1970, diphtheria was a common cause of crouplike symptoms. The vaccine has eliminated this infection with no cases reported in the United States in over 20 Differential Diagnoses Airway Foreign Body Bacterial Tracheitis Diphtheria Epiglottitis Inhalation Injury Laryngeal Fractures Laryngomalacia Measles Mononucleosis and Epstein-Barr Virus Infection Peritonsillar Abscess Approach Considerations Urgent care or emergency department treatment of croup depends on the degree of respiratory distress. In mild croup, a child may present with only a croupy cough and may require nothing more than parental reassurance, given alertness, baseline minimal respiratory distress, proper oxygenation, and stable fluid status. The caregivers may only need education regarding the course of the disease and supportive homecare guidelines. However, any infant/child who presents with significant respiratory distress/complaints with stridor at rest must have a thorough clinical evaluation to ensure the patency of the airway and maintenance of effective oxygenation and ventilation. Keep young children as comfortable as possible, allowing him or her to remain in a parent's arms and avoiding unnecessary painful interventions that may cause agitation, respiratory distress, and lead to increased oxygen requirements. Persistent crying increases oxygen demands, and respiratory muscle fatigue can worsen the obstruction. Concurrently, careful monitoring of the heart rate (for tachycardia), respiratory rate (for tachypnea), respiratory mechanics (for sternal wall retractions), and pulse oximetry (for hypoxia) are important. Assessment of the patient’s hydration status, given the risk of increased insensible losses from fever and tachypnea, along with a history of decreased oral intake, is also imperative. Infants and children with severe respiratory distress or compromise may require 100% oxygenation with ventilation support, initially with a bag-valve-mask device. If the airway and breathing require further stabilization due to increasing respiratory fatigue and hence, worsening hypercarbia, (as evident by ABG) the patient should be intubated with an endotracheal tube. Intubation should be accomplished with an endotracheal tube that is 0.5-1 mm smaller than predicted. Once airway stabilization is achieved, these patients are transferred for their ongoing care to a pediatric intensive care unit. The current cornerstones of treatment in the urgent care clinics or emergency departments are corticosteroids and nebulized epinephrine; steroids have proven beneficial in severe, moderate, and even mild croup.[22] In the straightforward cases of croup, antibiotics are not prescribed, as the primary cause is viral. Lack of improvement or worsening of symptoms can be due to a secondary bacterial process, which would require the use of antimicrobials for treatment. Typically, these patients initially would have had moderate-to-severe croup scores, requiring inpatient care and observation. Corticosteroids Corticosteroids are beneficial due to their anti-inflammatory action, whereby laryngeal mucosal edema is decreased. They also decrease the need for salvage nebulized epinephrine. Corticosteroids may be warranted even in those children who present with mild symptoms. Treatment of croup with corticosteroids has not shown significant adverse effects; however despite the low risk, their use should be carefully evaluated for children with diabetes, an underlying immunocompromised state, or those recently exposed to or diagnosed with varicella or tuberculosis, due to the potential risk of exacerbating the systemic disease process. A single dose of dexamethasone has been shown to be effective in reducing the overall severity of croup, if administered within the first 4-24 hours after the onset of illness. The long half-life of dexamethasone (36-54 h) often allows for a single injection or dose to cover the usual symptom duration. Studies have shown that dexamethasone dosed at 0.15 mg/kg is as effective as 0.3 mg/kg or 0.6 mg/kg (with a maximum daily dose of 10 mg) in relieving the symptoms of mild-to-moderate croup. Despite this knowledge, clinicians still tend to favor the dose of 0.6 mg/kg for initial treatment of croup. This dosage, in fact, is more effective for patients diagnosed with severe croup and remains the optimal amount for safety, benefit and cost-effectiveness.[33, 34] Dexamethasone has shown the same efficacy if administered intravenously, intramuscularly, or orally.[35] The route of administration is patient-dependent as based on the patient’s age, ability to tolerate orals, an severity of presenting illness. The use of inhaled corticosteroids (budesonide) with systemic treatment does not provide additional benefit.[36] Patients given a single oral dose of prednisolone (1 mg/kg) were found to have made more return visits than did those who received a single oral dose of dexamethasone (0.15 mg/kg).[37] This is due to the lesser potency to reduce inflammation and shortened half-life of prednisolone (18-36 h) when compared with ble inspiratory stridor (see the image below). Cool mist administration Throughout the 19th and most of the 20th century, cool mist administration was the mainstay of treatment. Hospitals had "croup rooms" filled with cool mist. Theoretically, mist moistens airway secretions, decreases their viscosity, and soothes the inflamed mucosa. Animal data show that microaerosol inhalation activates mechanoreceptors that produce a reflex slowing of respiratory flow rate and leads to improved airflow. However, despite its continued widespread use, little evidence supports the clinical efficacy of cool mist or humidification therapy. Randomized studies of children with moderate-to-severe croup revealed no difference in outcome between those who received cool mist and those who did not.[23] Mist tents, used in the hospital setting, can disperse fungus and molds if not properly cleaned. More importantly, the tents separate the child from the parent by creating a “plastic barrier," causing anxiety and agitation, potentially worsening the child’s symptoms and hindering ongoing clinical assessment.[24, 25, 26] In the home, vaporizers (heated humidification) producing hot steam to moisten the air should not be used because of the risk of scalding or burns.[27] Epinephrine Nebulized racemic epinephrine is a 1:1 mixture of dextro (D) isomers and levo (L) isomers of epinephrine with the L form (Lepinephrine) as the active component. Its use is typically reserved for patients in the hospital setting with moderate-to-severe respiratory distress. Epinephrine works by adrenergic stimulation, which causes constriction of the precapillary arterioles, thereby decreasing capillary hydrostatic pressure. This leads to fluid resorption from the interstitium and improvement in the laryngeal mucosal edema.[22] Epinephrine’s beta2-adrenergic activity leads to bronchial smooth muscle relaxation and bronchodilation. Its effectiveness is immediate with evidence of therapeutic benefit within the first 30 minutes and then, lasts from 90-120 minutes (1.5-2 h). Patients who receive nebulized racemic epinephrine in the emergency department should be observed for at least 3 hours post last treatment because of concerns for a return of bronchospasm, worsening respiratory distress, and/or persistent tachycardia. Patients can be discharged home only if they demonstrate healthy color, good air entry, baseline consciousness, and no stridor at rest and have received a dose of corticosteroids