File - ED 400 History and Philosophy of Art Education

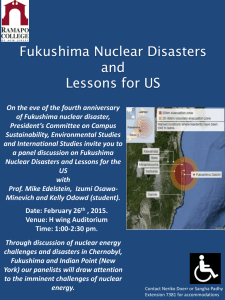

advertisement

Jessica Kelley ED 400 Art Commentary: Fukushima Hideko’s Work 109 I was immediately drawn to Fukushima Hideko's Work 109. I looked at it and thought, 'Wow, it's like an even more abstract de Kooning' which doesn't make much sense except that the way the paint is aggressively placed on the canvas reminds me of de Kooning. The paintbrush that made these marks, all of them, was quick. It moved furiously across the canvas. There is a struggle here. Warm and cool, in front and behind. It seems as if there are two elements in the battle, bobbing and weaving in fluidity. The blues were here first but just because they are blue does not mean that they are passive. They are dark, sometimes turning closer to black than the red ever gets. The red attacks and the blues defend. Or does the blue come from behind, silent? The red drips in a way the blue does not. Is it blood? Is it rage? An island appears on the bottom left of the canvas. Earth tones with green tree-like forms in an aerial view. The red fans out near the top of its form and becomes less and less defined as it falls in drips that have rolled off the bottom of the canvas. Black rings fade in and out along the right side of the piece. They appear to be made by placing a round object, or the rim of a round object, in black paint and stamped over and over again. I know this yet I can think of nothing but cigarette burns. Maybe honeycomb? No, a cigarette. Black paint cigarette burn marks. There is tension between the two represented entities. They do not mix. There is no one place where the angry red and reactive blue combine to form a purple; which is what they would make if they could get along. But they do not. In the bottom third, center-left, is a texturized, desaturated bluish-gray. Even though the black rings are on top of the red, they feel very much a part of it. This bluegray is different. It has a texture not present in the rest of the piece. It sits on top of the red and drips down with it. Is this a fire? A village on fire with scratchy, drippy reds? Is this textured blue-gray an attempt to diminish the flames? Although it seems small compared to the red, it is believable that it can win. The red is proud and large with its many shades ranging from pinks to reds to oranges. Black rings seem like soot and smoke. But the blue-gray would win because it is not made of many scratchy, drippy shades; it is one, unified color. It is scratchy in the same way the red is scratchy but at least it knows what color it is! Fire and water. Maybe there's more to this aerial view. An explosion in the sky, perhaps. The land is the only static portion of the image. Everything else moves with great urgency. Even though the blue-gray and red drip downward, there is a feeling of them rising before they fall. They both have dominant vertical brushstrokes that make it seem like they rose into the sky, clashed together, and are now falling in drips as they collide. The red is so large that when it flew into the sky, its form started to shift and change as its weight forced it to become unbalanced and spread apart. The blue-gay is more direct. Battle of colors Crashing Filling Layering From above No longer still The sky explodes Dripping Blinding Unavoidable Bursting Battle of colors Overpowering Anger Helplessness A beautifully tragic Battle of colors Female Japanese artist, Fukushima Hideko, painted Work 109 in 1959. During this time in Japan, artists were reacting to both the chaotic end to World War II and to the reconstruction that followed. In 1945, Tokyo was in ruins and was quickly occupied by opposing forces. “The Allied occupation signaled a radical time of transition. Japan embarked on reinventing itself from a defeated nation to a democratic citizen society by overcoming the nightmarish experiences and memories of the war and renegotiating its relations with the outside world” (Chong, 2012, pg. 29). However, artists of the late 1950s commonly expressed their views on the war. In speaking about another painting from this time period, Chong (2012) says, “All elements in the painting allude to the disaster, which was deeply painful for the Japanese citizenry – the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were only a decade old… This theme was clearly a touchstone for some other Japanese artists as well” (pg. 33). The radically changing social climate of Japan during the years 1955-1970 saw more female artists emerging. Fukushima Hideko was the only female member of an artist group known as Gutai. The group consisted of visual artists, musical composers, photographers, and an engineer. Chong (2012) describes Fukushima Hideko’s work with the following: “Fukushima, the only female member, could be described as the most ‘classical’ visual artist in the group; her principal mediums were painting and drawing, and her gestural brushstrokes and drips on canvas and gouache on paper were in many ways in line with gestural abstraction, which was becoming an important trend in painting. One particularly distinguishing factor in Fukushima’s pictures is her use of stamps made of cans – circular forms that contrast with the supposedly intentional incorporation of not-whollycontrollable material qualities and physical forces” (pg. 50). The initial interpretation of Hideko’s work was similar to its actual purpose. After researching the state that Japan was in during this time period, it becomes clear that Work 109 was a response to World War II. I was surprised to find that Hideko was a female artist because many of the abstract expressionist artists of that time were male. The painting shows a level of aggression and violence that, while not absent from the work of females, tends to suggest a male artist. Looking back at my previous responses to the piece, I had expressed the idea that the viewer was looking down on some sort of land with an explosion reaching into the air. This observation was clearly accurate to Hideko’s work during this time period. I discussed the repeating black circle shapes that are layered into the painting as being like cigarette burns or referring to soot and smoke. Knowing now that stamping a can in black paint is how the circles were made, it makes me think about the process of stamping as being related to the painting’s theme somehow. I am reminded of the Japanese internment camps and how Japanese people were made to live in camps similar to the way Jews in Germany were made to live in camps. Perhaps there is a relation between the stamping of numbers on the arms of prisoners to the stamping of the black circles on the painting. The repetition also reminds me of gunshots from an automatic weapon. After researching the Gutai art group, I looked back on Work 109 and found myself thinking more about the process of creating the piece. Knowing that the artist was most likely responding to WWII, I thought about the act of creating and how that could serve as a therapeutic act for her. The Gutai artists were concerned with the experiential elements of art and would challenge themselves to paint without paintbrushes. I imagine that the act of creating Work 109 was freeing to Fukushima Hideko. After nuclear war tore apart her country and she had felt the oppression of an occupied state, I don’t believe she used a paintbrush at all. I picture this woman, in her reaction to the war and oppression, throwing paint onto the canvas in an act of freeing herself from her fear and anger. I found it interesting to see some of the other work that she created after Work 109. These later works are more carefully thought out, more structured with clean lines and geometric shapes. To me, this mimics the rebuilding of Japan after the war and, possibly, the rebuilding of the artist as well. BIBLIOGRAPHY 1. Chong, D. (2012). Tokyo 1955-1970: A New Avant-Garde. New York: The Museum of Modern Art