The War for Cuban Independence

advertisement

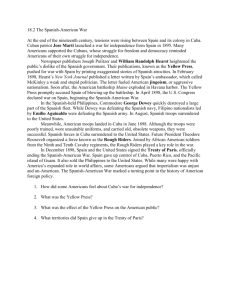

The War for Cuban Independence by Jerry A. Sierra Intro After careful planning by José Martí and a series of events that seemed to conspire against the Cuban rebels, the war of independence began on February 1895. This was the 3rd effort by the Cubans to free themselves from centuries of Spanish domination, reuniting many of the loved heroes of the Ten Year War: Antonio Maceo, Maximo Gómez, Flor Crombet, Calixto Garcia and others. The war for Cuban independence featured some of the most moving and dramatic moments in Cuban history; the death of Martí at Dos Rios, the western invasion and the military campaigns of Gómez and Maceo (the fox and the lion), the death of Maceo in December 1896, U.S. intervention in 1898 and the rising of the American flag over Havana after the Spanish flag was lowered on December 10 1898. 1. Before The War The dream of Cuban independence had existed for over one-hundred years before the final war for independence from Spain began in February 1895. It wasn't until the British occupation of Havana in June 1762 (shortly after England declared war on Spain) that Cuban planters were able to sell their goods on the open market. Under traditional Spanish rule, they sold their goods to the Spanish government, who set the prices and was their only legal customer. The government then sold the goods on the open market and kept the profits. The Cubans found it much more agreeable to sell their products to many buyers at competitive prices, and when the British and the Spanish traded Havana for Florida in 1763, Cuban businesses were forced back to the old oppressive system. Thus began the dream of Cuban independence By 1825, most of Spain’s colonies in the new world had achieved their independence, and only Cuba and Puerto Rico remained. Reacting to the prospect of a united Mexican-Colombian military expedition to help liberate Puerto Rico and Cuba in 1824, the U.S. government (with the backing of England) issued a series of threatening notes to Mexico and Colombia, declaring that the U.S. would “not remain indifferent” to the freeing of Cuba. The U.S. diplomat who delivered the threats wrote a revealing letter to his boss, Secretary of State Henry Clay, stating, “What I most dread is that that blacks may be armed and used as auxiliaries… This country prefers that Cuba and Porto Rico should remain dependent on Spain. This Government desires no political change of that condition.” The threats worked. The expedition was stopped before it began. Simón Bolívar told a delegation of Cuban revolutionaries, “We cannot set at defiance the American Government, in conjunction with that of England, determined on maintaining the authority of Spain over the islands of Cuba and Puerto Rico…” In 1868 landowner Carlos Manuel de Céspedes gave the legendary “Grito de Yara” (Cry of Yara) in which he freed his slaves and started the first war for Cuban independence, known as the Ten-Year War. Soon, the army of Mambises (as the rebels were called by the Spaniards) had become a legitimate guerilla-style army, with many victories and popular support. In time, however, the failure to successfully organize all aspects of the revolutionary effort, and the fact that the U.S. would sell the latest weapons to Spain, but not to the Cuban rebels, led to a stalemate in 1878 known as the Pact of Zanjón. The Pact ended the war, providing a general amnesty to anyone who fought and freeing the black slaves who fought on either side. Many were disappointed with the Pact, however, calling it a false promise that would never be kept. Their warnings would soon be proved truthful. In 1880, as the U.S. government prepared for overseas expansion, wiping out Native American resistance in the West and building an offensive Navy, U.S. investment in Cuba increased rapidly. While six percent of Cuban exports went to Spain, a whopping eighty-six percent went to the U.S. It was at this time that La Guerra Chiquita (The Little War) was fought. Led by Major Calixto García, a well-known leader of the Ten-Year War, and José Maceo, the new struggle for independence was crushed within months By 1894, less than 20% of sugar mill owners in Cuba were Cubans, and more than 95% of all Cuban sugar exports went to the U.S. José Martí and The Cuban Revolutionary Party Cuba’s second war of independence began in 1895, after years of meticulous planning by José Martí, who united some of the surviving veterans of The Ten Year War; Antonio Maceo, Máximo Gómez, Calixto García and others. Under Martí’s guidance, the rebels were organized into a cohesive, connected force that included a civilian government that would take over after the war. From the early months of 1892 Martí devoted himself exclusively to the cause of Cuban independence, soliciting and receiving financial support from Cuban exiles in all walks of life, and organizing every detail of The Cuban Revolutionary Party. At the end of March 1894, Martí began to push for immediate revolutionary action, writing letters to Maxímo Gómez and Antonio Maceo. In a detailed and informative account of the conflict, titled: The Spanish-Cuban-American War and the Birth of American Imperialism, historian Philip S. Foner sheds light on his urgency: “Martí’s impatience to start the revolution for independence was affected by his growing fear that the imperialist forces in the United States would succeed in annexing Cuba before the revolution could liberate the island from Spain.” Martí had noticed a frightening new trend of aggressive U.S. “influence,” evident by Secretary of State James G. Blaine’s expressed ideals that all of Central and South America would some day fall to the U.S. “That rich island,” Blaine wrote on December 1 1881, “the key to the Gulf of Mexico, is, though in the hands of Spain, a part of the American commercial system… If ever ceasing to be Spanish, Cuba must necessarily become American and not fall under any other European domination.” Blaine’s vision did not allow the existence of an independent Cuba. Foner writes, “Martí noticed with alarm the movement to annex Hawaii, viewing it as establishing a pattern for Cuba…” On the very day that Martí's revolutionary expedition was to set sail from Florida in January of 1895, the U.S. government confiscated three ships (the Amadis, the Lagonda & the Baracoa) loaded with weapons and supplies that had been difficult and costly to obtain. They promptly alerted the Spanish government. Not to be dissuaded, on March 25 Martí presented the Proclamation of Montecristi (Manifesto de Montecristi) which outlined the policy for Cuba’s war of independence: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. the war was to be waged by blacks and whites alike; participation of all blacks was crucial for victory; Spaniards who did not object to the war effort should be spared, private rural properties should not be damaged; and the revolution should bring new economic life to Cuba. By the end of March, Antonio Maceo returned to Cuba, ready to resume his vital role in Cuba's struggle for independence. On April 11 he was joined by Máximo Gómez, the military leader, and José Martí. They landed on the eastern shore of the island and joined bands of guerrilla forces that awaited their arrival. (Six decades later, Castro and his followers reenacted Martí's plan of battle in the Sierra Maestra, the very same mountain range.) 2. The War Begins When the war of independence finally began in early 1895, Spanish forces in Cuba numbered about 80,000. Of these, 20,000 were regular Spanish troops, and 60,000 were Spanish and Cuban Volunteers. The “Volunteers” were a locally prepared and assembled force that took care of most of the “guard and police” duties on the island. Wealthy landowners would “volunteer” a number of their slaves to serve in this force, which was under local control and not under official military command. By December, 98,412 regular troops had been sent to the island, and the number of Volunteers increased to 63,000 men. By the end of 1897, there were 240,000 regulars and 60,000 irregulars on the island. Numerically speaking, the Mambises didn’t have a prayer. The Mambises The word “mambises” originated in Santo Domingo, after a brave Negro Spanish officer (Juan Ethninius Mamby) joined the Dominicans in the fight for independence in 1846. The Spanish soldiers referred to the insurgents as “the men of Mamby,” and “mambies.” When Cuba’s first war of independence (known as the Ten Year War) broke out in 1868, some of the same soldiers were assigned to the island, importing what had, by then, become a derogatory Spanish slur. The Cuban rebels adopted the name with pride. Weapons and Ammunition Since the very beginning of the war, one of the most serious problems for the rebels was the acquisition of suitable weapons. Since the end of the Ten-Year War, possession of weapons by private individuals had been prohibited, so the only ones allowed to own weapons were Spaniards and Spanish soldiers, who had the combined benefits of modern weapons and training. The rebels had no choice but to become effective guerrilla-style warriors using the environment, the element of surprise, a fast horse and a machete. They were often short on weapons and ammunitions, and sometimes the weapons on hand were old, and the ammunition available not suitable. Most of the weapons used by the Mambises were acquired in raids on the Spaniards. Since Spain controlled the sea, and the mambises had no navy, it became nearly impossible to import weapons from the outside. Between June 11 1895 and November 30 1897, a total of sixty expeditions attempted to bring weapons and supplies to the rebels. Of those, only one succeeded. Twenty-eight attempts were hampered by the U.S. Treasury Department; 5 were prevented by the U.S. Navy Dept., 4 were interrupted by the Spanish naval patrol; 2 were wrecked; one was driven back to port by storm; 1 succeeded through the protection of the British; the fate of another is unknown. The Death of Martí On his first battle against the Spanish royalist army at Dos Rios, revolutionary icon José Martí was killed. The rebels tried, in vain, to recover his dead body, but were not able to do so. He was buried by Spanish soldiers on May 27 1895. Instead of squashing the spirit of revolution, Martí’s death inspired the rebel cause and sent ripples of nationalism throughout the island. General Martínez Campos and the “trocha” Credited with the Spanish victory in the Ten Year War, General Martínez Campos expected that the same strategy would help wipe out the rebels in 1895. The trocha was "a broad belt across the island," about two hundred yards wide and fifty miles long, designed to limit rebel movement to the eastern provinces. Down the center, a single-track military railroad was equipped with armor-clad cars, and various forts and fortified blockhouses were built alongside. A maze of barbed wire was placed so that every twelve yards of posts had 450 yards of barbed-wire fencing. The fortified houses featured loopholes and trenches on the outside, and many encircled windows from which Spanish soldiers could observe and fire. The eastern trocha ran from Jucaro on the south coast to Moron on the north. "As a final defense," wrote Foner in The Spanish-Cuban-American War, "bombs were placed at points most likely to be attacked, and these had wire attachments to enable their being set off in 'booby trap' fashion." Because the rebels always managed to have help and information from peasants, they were able to cross the trocha as they pleased. Maceo in Havana From the early planning stages the rebels deemed it necessary to bring the war to the Western provinces (Matanzas, Havana and Pinar del Rio) where the island's government and wealth was located. This was an important factor, since the failed Ten Year War had been kept to the eastern provinces by the various "trochas" and concentrated Spanish forces. The rebels divided their forces into two units; the Liberating Army would remain in the eastern provinces of Oriente and Camagüey, and the Invading Army, headed by Gómez and Maceo (known collectively in the Spanish press as the fox and the lion) would head west. In ninety days and 78 marches, the Invading army went from Baraguá (at the eastern tip of the island) to Mantua (the western end) traveling a total of 1,696 kilometers and fighting 27 battles against numerically superior forces. A number of war historians have agreed that the western invasion of Cuba was one of the great military achievements of the 19th century. Weyler the Butcher The war was not going well for Spain, and General Martínez Campos was forced to resign in shame during the early days of January 1896. This was a great symbolic victory for the Mambises, since Campos had been credited with the Spanish "victory" in the Ten Year War eighteen years earlier. Within a few days of Campos' resignation, General Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau (nicknamed the "butcher") was sent to Havana as a replacement. One of Weyler’s first orders was the fortification of the “trochas.” The modernized “trocha” featured electric lights across the narrow waist of the island from Mariel to Majana, on the border of Havana and Pinar Del Rio. He ordered 14,000 soldiers to be placed in key fortified positions along the “trocha.” After the new “trocha” was in place, Weyler concentrated his efforts on pursuing Maceo. He sent 3,000 veteran troops, under the command of General Suárez Inclán, to attack Maceo’s forces, which at the time totaled 250 men. Another tool implemented by Weyler was the system of “re-concentration,” in which various fortified areas were designated, and all inhabitants were given eight days to move in, including cattle and other animals. Anyone caught outside was considered the enemy and killed. These “re-concentration” towns were very crowded and unhealthy, since Spaniards and soldiers occupied the best accommodations and took the best food. Many died of disease and starvation. The Death of Maceo On December 3 1896, Maceo decided that the best way to get around the new, fortified trocha was by water at the port of Mariel. Carlos Soto, a local soldier, was selected to act as a guide, and Maceo handpicked seventeen men to go with him to the East. Riding with Maceo was Panchito Gómez Toro, (Máximo Gómez' son) who would not be dissuaded, by his father or anyone else, to join Maceo in Pinar del Rio. It took four trips of a crowded small boat on the following night, at about eleven thirty, to get across, all within sight of a resting Spanish garrison. They took refuge in an abandoned sugar mill called La Merced for two days. On December 6, frustrated that the horses and supplies that were supposed to greet them had not arrived, Maceo ordered that they start walking. Because of recent leg wounds, Maceo had a very difficult time walking or staying on his feet, although he could fight on a horse as fiercely and bravely as ever. On the road they met the rebel contingent with their horses and supplies, led by Lieutenant Colonel Baldomero Acosta. That night Maceo decided to join the forces of Colonel Silverio Sánchez Figueras, chief of the Brigade of Southern Havana, at San Pedro de Hernández, near the border of Havana and Pinar del Río. They formulated a new plan to assault the town of Marianao, on the outskirts of Havana. Resting his wounds on a hammock in San Pedro, as José Miró read from the Crónicas de Guerra (a document describing the war effort) the rebels were surprised by an enemy attack. Helped to his horse by two men, Maceo pursued the attackers with a machete and a revolver. He leaned towards Miró and said, “Esto va bien!” (This is going well!) A bullet struck him in the face, knocking him off his horse. As the men helped him back on the horse, another bullet struck him in the chest. The Spaniards did not recognize Maceo's body, nor were they aware that he had joined Figueras' forces, or they would have taken greater care to guard the corpses. That night, a handful of rebels snuck into the Spanish camp recovered Maceo's body. On December 8 Maceo was buried with Panchito Gómez Toro (Máximo Gomez’ son) at a secret location in Cocahual, at Santiago de Las Vegas. The war did not end with Maceo's death. Even without the Bronze Titan (as Maceo is remembered) the Mambises were more than the Spaniards could handle. Spain was virtually whipped when the U.S. intervened in 1898. The War Continues Since the time of Maceo's death, until April 1898 when the U.S. entered the war, Máximo Gómez had a column of 3,000 men. The rebels had 41 encounters with the 40,000 Spanish soldiers, cavalry and infantry, stationed south of Las Villas. In various battles, such as the battle of La Reforma, Gómez unquestionably defeated Weyler. The Spaniards were kept on the defensive, and the Mambises initiated every military operation in this area. One of the most dramatic victories for the Mambises was in Las Tunas, which had been renamed by the Spaniards as Victoria de Las Tunas, in memory of past Spanish victories during the Ten Year War. The town was guarded by over 1,000 well-armed-and-supplied men. On the morning of August 28 1877, General Calixto García gave word to attack. On August 30, Spanish Lieutenant Mediavilla appeared carrying a white flag under orders of Commander Civera to discuss terms of surrender. “I offered him liberty for himself and his comrades,” wrote Calixto Garcia to Gomez, “the surrender was verified by the turning over of the remaining forts. I have taken more than a thousand rifles and a million bullets. In addition, I have obtained 10 wagon loads of medicine, many machetes, several cannons, and an infinity of cavalry supplies plus supplies of clothing, edibles, etc. The prisoners consist of a chief, two doctors, ten officers, 380 soldiers plus 100 odd non-combatants and volunteers who were armed and fought during the siege. “I cannot help showing that I am highly satisfied with the conduct of the officers and soldiers who took part in the operations of Las Tunas. I feel true satisfaction in telling you that all of them knew how to stay at their posts with no exception whatsoever.” It was at about this time that the Philippines declared their independence from Spain, who also faced the possibility of threatened uprising in Puerto Rico. Spain was now fighting two wars—in Cuba and in the Philippines, which further weakened her already unstable economy. A series of secret dialogues to end the war took place between Spain (who was virtually whipped) and the U.S. (who wanted to purchase Cuba and had, by this time, made various offers that Spain had turned down). Learning of the secret negotiations, Estrada Palma and other Cuban leaders in New York announced that “only independence and Spanish withdrawal would end the war.” “We Cubans will never accept autonomy or reform,” said Estrada Palma, “we are fighting for independence and we will accept peace only on the condition of separating completely from Spain.” In Cuba, Gómez and García issued a statement asserting these very principles and listing twenty facts to prove that Spain had completely failed to crush the rebellion, which was now flourishing better than ever. Among these facts was the election of the Assembly, the siege and capture of Las Tunas by the Liberating Army, the complete civil and military organization maintained by the Republic of Cuba, and more. "Brutal repression had failed," wrote Foner. "Autonomy had failed. Military strategy had also failed. The strategy of reinforced trochas and concentration camps to deprive the rebels of civilian support and eventually grind them down, had failed. "On the other hand, Gómez's strategy of making the island economically undesirable for Spain had an overpowering effect. Nearly all economic production was at a standstill, and practically everything of value in the island was devastated." Weyler was replaced by Don Ramón Blanco y Arenas in October 1897, and sadly for the cause of Cuban independence, the U.S replaced Spain a year later as the official government of the island. 3. U.S. Intervention It's been suggested that a major reason for the U.S. war against Spain was the fierce competition emerging between Joseph Pulitzer's New York World and William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal. Their increasing circulation was based on what we now call "yellow journalism" and marks the darkest, most shameful hour for the profession of journalism. Others argue that the main reason the U.S. entered the war was a failed secret attempt, in 1896, to purchase Cuba from a weaker, war-depleted Spain. From the beginning of the war, Hearst reported the exploits of the "courageous freedom fighters," an opinion not shared by the State Department. Pulitzer had originally opposed U.S. involvement, but had a change of heart. [Years later he admitted that the only reason he changed his mind was the opportunity to increase circulation.] Their combined coverage of the war was nothing but an imaginative competition of exaggerations and outright lies. "Upon the already biased reports from Cuba," wrote Joseph E. Wisan in an essay titled "The Cuban Crisis As Reflected In The New York Press," published in American Imperialism in 1898, "the home offices of the newspapers built further. Artists far removed from the Cuban scene illustrated reports vividly but inaccurately; cartoonists magnified atrocities; feature writers, Sunday supplement writers, even contributors to women's pages added their prejudiced efforts. With so much information and misinformation from which to choose, editorial writers knew no bounds." "In the opinion of the writer," Wisan states elsewhere in the essay, " the Spanish-American War would not have occurred had not the appearance of Hearst in New York journalism precipitated a bitter battle for newspaper circulation." Writing in New York's Saturday Review, Winston Churchill expressed reluctant concern at the fact that "two-thirds of the Cuban rebels were black," adding that it would be beneficial to U.S. interests if Spain kept control of the island. Faced with a revved up, war-ready population, and all the editorial encouragement the two competitors could muster, the U.S. jumped at the opportunity to get involved and showcase its new steam-powered Navy. On January 24 1898, President William McKinley sent the USS Maine to Havana to "protect American lives and property." At 9:40 p.m. on February 15, while sitting on the harbor at Havana, a freak accident, or an act of sabotage, caused an explosion that sent 260 sailors to their deaths and the battleship Maine to the ocean floor. The Maine was among the first ship of her type built for the new U.S. Navy, a new line of steelhulled, steam-powered battleships. At 324 feet long, she was the largest warship built in the U.S. at the time. [In 1974 Navy Admiral Hyman Rickover conducted a study that concluded the explosion had started by spontaneous combustion in some accumulated coal dust in one of the ship's coal storage bunkers. The heat from this fire, Rickover says, ignited the ammunition magazine and blew up the ship.] By the time the U.S. entered the war in 1898, Spain was running for cover, and a Cuban victory was certain. The Spanish troops had been forced back into the urban areas, making them easy targets. The rebels controlled the countryside, and the Spaniards found it impossible to retreat. “REMEMBER THE MAINE” Three days after the explosion, William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal became the first newspaper in history to sell over one million copies. Inspired by Pulitzer and Hearst's official war slogan Remember The Maine, the U.S. decided it was time to enter the war. On April 19 the U.S. Congress (by a vote of 311 to 6 in the House and 42 to 35 in the Senate) adopted the Joint Resolution for War with Spain, which included the Teller Amendment, named after Colorado Senator Henry Moore Teller. The amendment disclaimed any intention on the part of the U.S. to exercise jurisdiction or control over Cuba for other than pacification reasons, and confirmed that the armed forces would be removed once the war is over. The amendment, pushed through at the last minute by anti-imperialists in the Senate, made no mention of the Philippines, Guam, or Puerto Rico. The U.S. congress formally declared war on April 25. Teddy Roosevelt, who eventually became a U.S. president, was so eager to make a name for himself that he resigned his post as Assistant Secretary of the Navy in order to join the war and claim his "chance at glory." In a mad rush for notoriety, Roosevelt personally financed the expedition and outfitted his troops. It was Roosevelt's "Rough Riders" that took San Juan Hill away from the depleted Spanish defenders. Legend tells how Roosevelt, with a saber in one hand and a pistol in the other, led his Rough Riders and the Ninth Cavalry, an African American regiment, to the sounds of "Charge!" The Battle of Santiago Bay, between the Spanish and U.S. naval forces, ended centuries of Spanish power in the Western hemisphere. 1,800 Spaniards died in the battle, in contrast to one American. The Spanish ships were beached, burning or sinking, and two weeks later the Spanish forces in Santiago surrendered. In the Pacific, the aging Spanish fleet was no match for the new steam-powered American navy, and the war didn't last long. On August 11 Spain accepted the peace terms, in which the U.S. received control of 4 new territories: Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Guam. The U.S. had also recently annexed Hawaii, Samoa and Wake Island. Although the treaty officially granted Cuba's independence, it was the U.S. flag, not the Cuban flag, that was raised over Havana, and during the surrender ceremonies in Santiago de Cuba, U.S. General William R. Shafter refused to allow Cuban General Calixto García and his rebel forces to participate. Spain received payment of $20-million for Guam, Puerto Rico and the Philippines. A total of 274,000 U.S. soldiers were sent to Cuba. Of the 5,462 who died, only 379 were killed in battle. The others died from tropical disease and unspecified "other causes," including malaria, yellow fever, and dysentery, most of which can be attributed to 500,000 pounds of beef purchased by the U.S. Army from Armour & Co. Meatpackers. (The very same shipment of meat had been sent to Liverpool a year earlier, but was rejected.) Contrary to popular perceptions and many current books on U.S. history, the Spanish-CubanAmerican War, dubbed "a splendid little war" by Secretary of State John Hay, was fought largely by African-American men. Of the Americans who died, most were African-American. 4. After The War "After more than three years of 'total war,'" wrote Foner in The Spanish-Cuban-American War, Vol. 2, "Cuba lay in ruins. The armies of Spain and Cuba had swept back and forth over the land, carrying ruin with the torch at every trip. What was missed by one army was destroyed by the other." An American military government was immediately proclaimed in Cuba, with General John R. Brooke as commander. Martí's revolutionary government was never allowed to take control. On January 1 1899, General Brooke took formal control of Havana from the retiring Spanish governor-general, but the occasion was completely American, and Cubans were denied the longanticipated satisfaction of parading their troops through the capital. After the Spanish flag was lowered, the U.S. flag was raised. “Cuba cannot have true moral peace,” wrote General Máximo Gómez in his diary on January 8 1899, “which is what the people need for their happiness and good fortune – under the transitional government. This transitional government was imposed by force by a foreign power and, therefore, is illegitimate and incompatible with the principles that the entire country has been upholding for so long and in the defense of which half of its sons have given their lives and all of its wealth has been consumed.” In December 1899 General Leonard Wood replaced General Brooke. Along with the military occupation, commercial and business interests invaded the island, assured of every possible cooperation from the new government. An article in the New York World on July 20 1898, predicted a new invasion of Cuba following the war. “Whatever may be decided as to the political future of Cuba,” the article stated, “it’s industrial and commercial future will be directed by American enterprise with American capital.” The predictions turned out to be correct. The provisional military governments, which controlled Cuban money, refused to provide loans to farmers and landowners to get their crops in shape, using this money instead for roads and sanitation. As a result, American entrepreneurs such as United Fruit Company president Andrew W. Preston, railroad financier Stuyvesant Fish, sugar baron Henry D. Havemeyer and others were able to come in and purchase dirt-cheap farmlands and other properties. Its widely speculated that the economic and social future of the island would have been more agreeable to Cubans if the military government had followed, instead, a policy of helping the small farmers and planters to resume production. “This was the legacy of American military occupation,” wrote Foner, “and the refusal to permit the use of the funds belonging to the Cuban people to assist the small farmers and planters to retain their land and rebuild their properties, damaged or destroyed during the Revolution. …Americans were most ‘energetic’ in picking up land at low prices from people who were without means, and for whom the Occupation government refused to provide loans so that they could develop their property.” By February 1899, barely six weeks after the formal opening of the Occupation, the process of disposing franchises, railway grants, street line concessions, electric light monopolies and similar privileges in Cuba to foreign syndicates and individual capitalists was about to begin. The U.S. War Department created a new board for this very purpose, with General Robert P. Kennedy of Ohio as its official leader. The move was opposed by J.B. Foraker, the Senator from Ohio, who introduced legislation (the Foraker Amendment) making these franchises and concessions illegal. This did not, however, "prevent leading American industrialists and financiers from taking over railroads, mines, and sugar properties," wrote Foner, "nor did it stop the military government from aiding them in these ventures." As a result, the sugar and tobacco industries, once controlled by the Spanish, now came to be controlled not by Cubans, but by Americans. General Wood believed, as did many expansionists in the U.S., that Cuba would, and should, become a state of the Union. Many strong and loud voices advised the U.S. to ignore the Teller Amendment (which prevented the annexation of the island). Editorials in major U.S. newspapers, and the rhetoric of many in the McKinley administration, favored ignoring the law and annexing Cuba. When that option no longer seemed prudent, rumors and articles began to circulate claiming that the Teller Amendment did not apply because the majority of the Cubans wanted to be annexed. But that was just not the case. “It was clear at all stages of the Occupation,” wrote Foner, “that the annexationists constituted a distinct minority in Cuba. The vast majority of the Cubans insisted on independence. This had been their aspiration for half a century, and for this they had made untold sacrifices. They insisted, too, that the United States live up to its promise. The expression of the will of the majority of the Cuban people doomed the effort in the United States to undo the Teller Amendment. In the end, the annexationists had to concede that their goal was impossible to achieve.” An editorial in the New York Sun, on April 13 1900, summed up the annexationist point of view. “The attitude of the people of Cuba toward annexation seems to be this in brief; the wealth and intelligence of the island are generally in favor of it, and the agitators and their tools, the ignorant Negroes, are opposed to it.” The editorial went on to suggest that U.S. policy should follow the island’s wealth and sophistication. Cuba’s first elections took place on June 16 1900. Guided by an electoral law based on U.S. Secretary of War Elihu Root’s plan for a restricted vote, it was deemed that voters must be male, over twenty-one years of age, citizens of Cuba according to the terms of the Treaty of Paris, and they must fulfill at least one of three alternative requirements; be able to read and write; own property worth $250 in U.S. gold; or have served in the Cuban army prior to July 18 1898, with an honorable discharge. Election results were a resounding defeat for annexationists. The Cuban National Party, made up of the revolutionary element, won the most votes in almost every city, and the Democratic Union Party, which represented Cuban moneyed interests and openly in favor of annexation to the U.S., lost in every election. The emergent Platt Amendment made a pseudo-colony out of Cuba, imposing a number of conditions that turned Cuban independence into an unfulfilled dream. “Cuba,” the Platt Amendment proclaimed, “should make no treaty that would impair her sovereignty, she should contract no foreign debt whose interest could not be paid through ordinary revenues after defraying the current expenses of government.” It allowed for U.S. military intervention to “preserve” Cuban independence or the “maintenance of a government adequate for the protection of life, liberty, and property.” Cuban leaders were outraged, but the U.S. government would not budge, announcing that the new republic would have to accept the Platt Amendment in order for the military to leave the island. On March 2 1901, the Platt Amendment was incorporated into Cuba’s constitution. The Cuban flag did not fly over Havana until May 20 1902, when On May 20, 1902, crowds gather in Havana to watch the Cuban flag Tomás Estrada Palma raised over Morro Castle. was sworn in as the first president of the new Republic. In 1903, a Permanent Treaty gave the U.S. responsibility for “internal tranquility” and formalized U.S. use of Guantanamo Bay, an issue that remains a sore spot for Cubans to this day. -endNote: In October 1998, one hundred years after the war, Theodore Roosevelt was awarded the Medal of Honor.