span-am war

advertisement

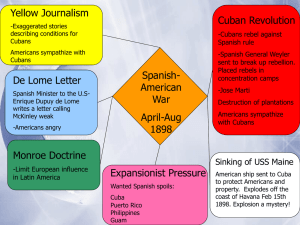

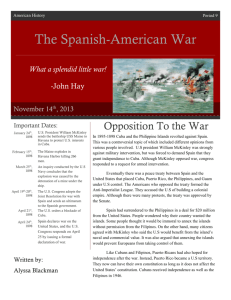

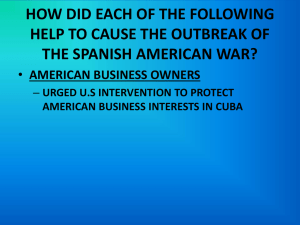

The Spanish-American War Background Cuba, 1895: Forces led by Máximo Gómez engage in guerilla warfare against Spanish. Seek to gain Cuban independence or provoke U.S. intervention. Spanish Response Spanish Governor General Valeriano Weyler removes rural population into camps Thousands die in camps Provokes humanitarian outcry U.S. public opinion becomes pro-intervention Reflected various concerns: Humanitarian Imperialistic Economic Assisted by “yellow journalism” Particularly re: coverage of the U.S.S. Maine (sinks Feb. 15, 1898) March 1898: President McKinley demands Cuban independence Rejected by Spain, April 10. Congress calls for Cuban independence, Spanish withdrawal, gives McKinley authority to use force. Spain declares war April 23; U.S., April 25. U.S. plans: Assumed war would be primarily a naval conflict U.S. Navy Army Would destroy Spanish naval forces Bombard cities or blockade territories Would man coastal defenses Small forces would be sent to assist Cuban rebels Primary focus: Cuba Naval mobilization goes smoothly Naval War College had previously developed plan for a war with Spain. Ships deployed into 5 squadrons: Asiatic – George Dewey North Atlantic – William T. Sampson “Flying” Squadron – Winfield Scott Schley Battle of Manila Bay: May 1, 1898 Meanwhile, in the Atlantic… In late April, Spain sends a squadron under Adm. Pascual de Cervera across the Atlantic Sampson’s squadron goes to Puerto Rico But Cervera learns of the fleet’s destination, heads to Santiago, Cuba instead. Sampson blockades Santiago, but too dangerous to send his fleet into the harbor. The Army: Manpower Legislation passed in April 1898: Allowed McKinley to call up state Guardsmen to serve as volunteers. Enlarged the regular army to 67,000 men. Provided for formation of some federal volunteer units. Volunteer call-up results in chaos McKinley calls out 125,000 Guardsmen in April, and another 75,000 in May. Army bureaucracy geared toward needs of peacetime establishment (about 25,000 men) Guardsmen arrive at camps not adequately trained or equipped. Mission to Cuba William R. Shafter appointed to command of 5th Corps, assembling in Tampa, FL. Original assignment modest, changed and ultimately sent to Santiago. Logistical disorder in Tampa Transportation bottlenecks Poor record-keeping Too few staff officers 5th Corps sails to Cuba, June 14-22 Shafter moves towards city of Santiago Battle of Santiago, July 1, 1898 Most famous combatant at San Juan Hill: Teddy Roosevelt Battle of Santiago: Aftermath Cervera’s fleet destroyed in escape attempt, July 3. Shafter demands surrender of Santiago. Leads to capitulation of commander of Spanish forces in eastern Cuba, July 17 Puerto Rico invaded, July 25. Peace protocol signed, August 12. Additional considerations Spanish leadership poor Role of Cuban guerillas Disease: ravages 5th Corps in Cuba breaks out in volunteer camps in U.S. Meanwhile, back in the Philippines… Emilio Aguinaldo returns to organize resistance to Spanish rule. Declares independence. Establishes a republic. Besieges Manila with an army. The “Battle” of Manila, August 13 U.S. forces capture the city Battle designed to: Save face for the Spanish Keep city out of hands of indigenous Filipino army Word of peace protocol arrives just after the battle. Treaty of Paris, Dec. 10, 1898 Spanish granted Cuba independence, withdrew from the Island. Spain ceded Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines to the U.S. Annexation of Philippines sparks outcry in U.S. (and costs $20) Birth of American Empire