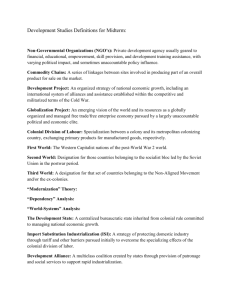

The International Development of Bretton Woods

advertisement