A Case for ESL Tutors: Comparing Conference

advertisement

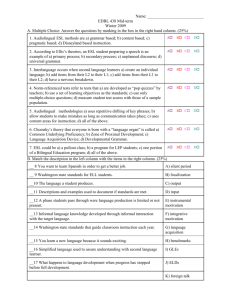

Hannah Furfaro English 316 12/8/09 A Case for ESL Tutors: Comparing Conference Strategies of ESL Tutors Versus Native Speaking Tutors in ESL Student Conferences Writing centers’ goal of facilitating campus-wide tutoring sessions for students in need have become increasingly popular on campuses nation wide. The place of the writing center on campus varies, and each center develops its own ideology and methodology on the “correct” way to approach writing tutoring. One debate that continues to evolve within the realm of writing center tutoring focuses on the role of teaching grammar versus composition strategies or traditionally “higher order” issues (such as organization and argumentation). Rhetorical grammar instruction has come under fire in recent years and is deemed by some academics as alienating and incompatible with other tutoring techniques. The role of teaching grammar as a meaningful way to approach students’ drafts is criticized as a fix-it approach; some argue more comprehensive methods that identify argument weakness or confusing organization structures should be a prerequisite for dealing with grammatical errors (Harris and Silva 526). In “Making a Case for Rhetorical Grammar” Laura Micciche contends teaching grammar is not as “mind-numbing” as some academics claim (716). Micciche complicates traditional interpretations of grammar and claims teaching rhetorical grammar is “as central to composition’s driving commitment to teach[ing] critical thinking and cultural criticism,” (717). She says rhetorical choices are reflective of the world the writer lives in and the connection between such grammatical choices and the expressive purpose of any paper are inherently related. Rhetorical grammar should be Furfaro, 2 chosen as a way to clearly reflect on and demonstrate relationships between ideas, rather than a “systematic application” of rules, Micciche argues (721). Theories on grammar instruction become more complicated in the context of tutoring sessions held with ESL students. An ESL student is defined as “anyone whose native language is not English, who is visiting the United States from another country to study at college or university, and who is in the process of learning to write (and speak) in English,” (Bruce and Rafoth, xiii). The debate on whether or not grammar instruction should be a focal point in writing conferences between writing tutors and their ESL tutees remains in flux based on multiple prevailing theories that disappear and reappear throughout the history of research on tutoring ESL students. Although many arguments seem to overlap with academics who address tutoring grammar in a general context, the unique position of ESL students obscures contemporary beliefs on how grammar should, or should not be taught. Some academics argue against using generalized theories on teaching grammar during writing center-tutoring sessions. Harris and Silva, in “Tutoring ESL Students: Issues and Options” argue against previous methods of comparing native English speakers rhetorical patterns with those of ESL students. They say such comparisons and “cataloging of differences” in an attempt to deal with ESL students’ grammatical errors is an underinclusive approach. Harris and Silva suggest that one way to avoid comparisons that are not all encompassing is to identify common problems associated with certain cultures (528). They caution against too broad of a homogenizing approach and emphasize that all individuals will likely exhibit some errors that do not conform to trends exhibited by native students or even students from a similar cultural Furfaro, 3 background. In “Rethinking Writing Center Conferencing Strategies for the ESL Writer,” Judith Powers argues that because ESL students have a different knowledge base of rhetorical skills than native speakers, strategies such as collaboration which are typically successful in writing center conferences with native speakers, will likely fall through in conferences with ESL students. “Since what these writers already know about writing is based in those first-language rhetoric’s, it is likely that attempts to use common collaborative strategies will backfire and lead them away from, not toward, the solutions they seek” (370). She says that because many techniques used in native speaker conferences rely on “shared assumptions” between the tutor and the tutee, these solutions will fail with ESL students who do not yet inherently assume the same things native speakers might assume (370). ESL students have a tendency to want to understand the “rules” of English which is often off-putting to native English speaking tutors who typically aim to focus on “higher order” concerns (Harris and Silva, 530). They explain this based on nonnative speakers lack of intuition on what sounds correct in English; thus, many ESL students become reliant on rules when they write and speak English. This reliance often becomes noticeable in conferences with ESL students when the student engages with the writing tutor as if the tutor was a copy editor rather than someone who can aid the student with organization or thesis issues (Harris and Silva, 529). Harris and Silva argue that tutors should prioritize rhetorical issues over linguistic errors. They discuss the necessity of acknowledging what students do well in a paper instead of focusing primarily on grammatical mistakes. Students should understand grammatical errors are a “natural part of language learning” (530). Content, a generally considered Furfaro, 4 higher order concern, should be prioritized over the lower order concern of grammatical changes (Harris and Silva, 526). Some academics say grammatical instruction is necessary for ESL students who are still learning the nuances of a new language (Celce-Murcia, 465). Some academics such as Marianne Celce-Murcia in “Grammar Pedagogy in Second and Foreign Language Teaching,” suggest that grammatical instruction and “surface-level” corrections make ESL students more confident about their finished product. Grammar instruction in the context of ESL students could be viewed as giving students a necessary set of tools to effectively communicate ideas in a language they are unfamiliar with. In a study cited by Marianne Celce-Murcia, 40 percent of ESL students at a university level were evaluated as having produced “fully acceptable” writing after grammatical corrections, while those same essays were rated “unacceptable” by university composition professors before the errors were corrected (465). CelceMurcia argues grammar should not be taught as an end in itself, but should be taught with “reference to meaning, social factors, or discourse” (467). Celce-Murcia concedes that grammar should never be the highest order of concern, but says understanding appropriate usage rules is critical for ESL students who may be otherwise unable to express concrete messages. In “ESL Writers: A Guide for Writing Center Tutors” Bruce and Rafoth argue that more often than not, when a tutor does some line-by-line editing, students begin to recognize patterns of error and quickly learn to self-edit (90). Bruce and Rafoth suggest an indirect approach by the writing tutor; they argue it is more productive for Furfaro, 5 the tutor to ask the student to look for the errors first before pointing out error locations. This exercise helps the student become a more independent editor of their own work and increases the students’ confidence in their ability to understand correct grammatical structures. In an attempt to synthesize and build on previous research on the role of grammatical instruction during ESL student writing conferences, I decided to look at the way native English speaking tutors versus ESL tutors handle grammatical issues. My study looks at the role grammatical instruction plays through two case studies involving ESL students and writing center tutors at the University of Wisconsin – Madison. My study looks at the differences between how a native speaking tutor addresses grammar with an ESL tutee versus how an ESL tutor addresses questions related to grammar. The debate surrounding whether or not grammar instruction should be a primary focus in conferences with ESL students, contextualized by my two case studies, brings me to the question of “what methods do native speaking tutors and ESL tutors use to address grammatical issues and to what extent do these methods affect attendance of ‘higher order concerns’?” My study also looks at how cultural differences or similarities between the tutors and their tutees contribute to the “success” of a conference. My study examines how such relationships either contribute to or prevent miscommunication during discussion of higher order concerns. My findings help me conclude that writing center tutors should help equip ESL students with the grammatical tools they need to write comprehensible drafts through a dialogue that accounts for the gravity of grammatical errors. My research also helps make the case that ESL tutors’ and their tutees’ potentially similarly situated cultural Furfaro, 6 backgrounds allow ESL tutors to more effectively address the grammatical needs of ESL writers. Methodology Four subjects were selected to participate in observation sessions at the UWMadison Writing Center; two writing center tutors and two ESL students. Each student met with one of the writing center tutors to discuss their papers, which were written for different courses. Both tutees were female and both writing center tutors were male. “Lily,” who worked with “Joe” (a native speaker), moved to the United States when she was ten years old. “Jen,” who worked with “Dave” (a non-native English speaker) moved to the United States to attend college and attended high school in her native country. With the students’ and tutors’ permission, one 30-minute writing conference was audio taped for each pair. Each students’ draft was written prior to the conference. Joe had never met with Lily to discuss a paper but Dave had worked with Jen on previous drafts of the paper they discussed during the recorded observation session I watched. In a comparable study that looked at the role conferences play between teachers and ESL students in a writing context, a comprehensive iterative process and set of codes was established to analyze the discourse between the teacher and the student. Using a similar approach, my study which evaluated the discourse exchange between writing center tutors and tutees used a scheme based on the one used in the comparable study with some addition of codes that seemed particularly relevant for this study. The following discourse features were evaluated: Furfaro, 7 Discourse Schemes Episode Subunit of the conference. Change in topic or purpose signifies a new episode. Topic Nomination The participant who introduces a new topic/purpose changes to a new episode. Invited Nomination Occurs when the participant nominates the topic in response to “what would you like to discuss?” Question A question asked by the ESL student or the writing center tutor Negotiation of Confirmation checks, comprehension checks, clarification Meaning requests Negotiation of Clarification of revision strategies: 1) student confirming the Revision tutors suggestion of a need for revision 2) teacher checking to see if the student understands the revision strategies 3) student checking to see if it is appropriate to revise in a certain way 4) student stating he/she did not understand why revision is necessary Interruption Change of speaker before the original speaker has completed a thought Change in Language Moving between languages (subset of negotiation of meaning) Backchannels Verbal devices such as year, um, etc. to indicate the listener is attending to the speaker Turn Change in speaker – discussion that does not include one of the above discourse schemes. Coding originally devised in Conrad and Goldstein, 1990. Rows 7-8 are original codes. The data collected in the conferences was transcribed from the audio recordings and then coded based on the discourse analysis system that synthesized Conrad and Goldstein’s scheme with original codes devised specifically for this study (‘interruption’ and ‘change in language’). Each statement a participant made could receive multiple codes; for example, a question that changes the topic or purpose of the conversation could receive a “question code” and a “topic nomination code.” After each Furfaro, 8 conference was coded, frequencies of each discourse scheme were calculated and compared. For the purpose of this study, the most significant area of interest comes from an examination of how frequently ESL students versus their tutors use “negotiation of meaning” discourse schemes. The goal of this research is to discover the approaches writing center tutors at UW-Madison use to address grammatical errors in ESL students papers and each discourse scheme coded under “negotiation of meaning” and “change in language” serve as points of interest for evaluating the tutors’ approach to correcting errors. Case One: Lily and Joe Lily, a non-native speaker, met with Joe at the UW-Madison Writing Center to work on a sociology paper about her family’s structure. Joe followed the prescribed writing center format during the conference; he encouraged Lily to read her paper aloud and contribute mutually to the discussion on the paper’s content as they went through paragraph-by-paragraph. Using the coding described above, I calculated how much “talk time” each participant contributed to the nine areas of discourse I coded. The primary areas I evaluated after calculating each participants frequencies allowed me to identify trends in particular discourse areas. Four primary trends emerged from the data I collected; Joe nominated topics more than four times as often as Lily, Joe asked more than four times as many questions as Lily, Lily negotiated grammatical meaning twice as many Furfaro, 9 times as Joe and Lily engaged in explanatory “talk time” (turns) four times as often as Joe. Discourse Distribution Data TN IN Q M R I L B T Joe 82% 100% 78% 33% 50% 58% n/a 60% 19% Lily 18% 0% 22% 67% 50% 42% n/a 40% 81% Although not all of these trends seem directly related to the use of grammar instruction, each of these trends gives useful information on the roles each participant played in the conference which provides some insight on the “meaning negotiations,” which are the focus of this study. The main discourse area I address in this study is negotiation of grammatical meaning, which includes confirmation checks, comprehension checks and clarification requests. These categories include discourse primarily focused on grammar, sentence structure and other linguistic rules. Negotiation of meaning also includes comprehension checks, which includes discourse between the two participants aimed at confirming that one participant understands the other participants meaning. Finally, negotiation of meaning includes clarification requests, which consist of one party asking the other party to explain their meaning (this subcategory is cross-listed with the code “question”). Excerpts from Lily and Joe’s conference displaying these types of negotiations are below. Overall, Lily asked for grammatical clarification, such as how to pluralize a noun correctly, twice as often as Joe. This statistic indicates Lily needed clarification on Furfaro, 10 potential grammatical errors and asked comprehension or clarification questions significantly more than Joe. Celce-Murcia argues that ESL students are likely to feel more comfortable with their drafts if their basic grammatical questions are answered than if they stay silent about errors they are concerned about (469). In the case of Lily, she did spend more time than Joe asking for comprehension and clarification help. Although this is interesting, the statistic becomes of more interest when contextualized by the actual conversation patterns, and types of “negotiation of meaning” phrases Joe and Lily used. Throughout the conference Lily initiated clarifications about her word choice and sentence structure through questions and indication of confusion. In an episode near the beginning of the conference after Lily finished reading her first paragraph, Lily and Joe discussed the placement of the word “structure” relative to the subject and verb in a sentence Lily included in her paper: Lily: “It is interesting to see how much cultural heritage shapes the structure interactions…” Do I say the “structure interactions? Can I do that? Joe: The structure … the interactions … ok yeah. Lily: I was just always taught I could have done it that way … Joe: Either way is fine. In this exchange, Lily asks Joe if the word “structure” is an OK modifier of the word “interactions.” She seems to realize something doesn't sound correct about her sentence but she is not sure if she is correct or incorrect in identifying an error. It is evident Joe is trying to understand where Lily sees a potential problem, but instead of helping her see the correct way to modify “interactions” is with the word “structural” rather than “structure,” he seems to lose focus and has problems aiding Lily. When she Furfaro, 11 says she was always taught to “do it that way,” Joe says, “Either way is fine.” Joe has a difficult time understanding Lily’s initial grammatical question, and seems to either want to brush aside her concern by consoling her with the vague statement “either way is fine” (it should be noted that Lily did not offer another option of how to word her sentence. Joe’s suggestion therefore seems out of place) or simply not understand what she is asking. To this instance is not an anomaly on Joe’s part, it is necessary to examine another case when Lily attempted to negotiate grammatical meaning. In another episode, this time near the middle of the conference, Lily was reading through her second paragraph when she asked another question about how to phrase a particular sentence: Lily: “Without question we do care about each other in our own way, however our relationship…” would have been much better? Is much better? If we are able to express … ? Joe: Don't worry about it for right now. Why don’t you bracket that off and we can come back to it. Although he offers to come back to the issue Lily brings up, the pair never goes back to address Lily’s question. In this exchange, Joe seemingly wanted to focus on his perception of “higher order issues” such as the content and ideas in Lily’s paper. Although Joe is not harsh, he makes it clear he wants to focus on higher order issues such as organization and content. A few “turns” after the exchange about bracketing off Lily’s concern, Joe says, “There’s so many good observations and thoughts in here but I feel like sometimes they get pushed to the background because of the organization. Maybe adding something to another paragraph? Maybe mapping onto these questions?” Joe continues to ask the sort of “collaborative” questions Power’s criticizes (when used Furfaro, 12 with ESL students) and as the pair progress to higher order concerns, Lily occasionally seems to become confused with Joe’s questions. As the conference progressed, Joe directed the conversation toward what he considered “higher order issues” without going back to address Lily’s personal concerns on grammar and usage. In an article by Jessica Williams and Carol Severino, they argue that tutors should focus on higher order concerns over grammatical instruction (167). In another article by Williams, called “Tutoring and Revision: Second Language Writers in the Writing Center,” she argues it is the role of the writer to detect grammatical issues and evaluate these problems themselves so they develop their own understanding “of how they want their text to evolve” (174). However, the drawbacks of silencing Lily’s concerns and forcing her to evaluate them herself became more apparent as the discussion continued; Lily expressed confusion rather than successfully engaging in Joe’s collaborative questions and she seemed to begin to doubt some of the fundamental arguments her paper made. Miscommunication began when Joe asked about the factors that contribute to Lily’s family’s power hierarchy (she devotes a section of her paper to discussion on this topic). Joe brings up content ideas Lily had not thought of and he suggests a different method of organization based on the new content. After this suggestion, Lily seems to shut down and become confused about what Joe is asking from her: Lily: Yeah. I am confused because I talk about this in the summary. Joe: You were saying everything seems to overlap. Lily: Yeah, I guess sometimes I can talk about it, how, and the thing that I didn’t really talk about because I think that I … I don’t know. Furfaro, 13 As Joe directed the conference in the direction he thought was useful, Lily seemed to feel less confident about her work as a whole. Ultimately, addressing “higher order concerns” without abating Lily’s concern about her grammatical errors proved fruitless, possibly because of Joe’s initial rejection of Lily’s grammatical questions. Lily seemed to lose confidence after her concerns were never addressed which made it more difficult for her to engage in Joe’s concerns. According to Powers, it is the context of the questions ESL students ask that matters; Powers says although some questions regarding form, thesis statements or usage may seem similar on face to the types of questions “lazy” or “insecure” native speakers might ask, what makes these questions different is the ESL students’ inherent unfamiliarity with the English language (373). “We were … unlikely to provide useful help to ESL writers until we saw the questions they raised about basic form and usage not as evasions of responsibility but as the real questions of writers struggling with an unfamiliar culture, audience, an rhetoric,” she says about her experience in the writing center at the University of Wyoming (373). Powers argues the tutors’ role should be as an “informant” rather than a “collaborator” when tutoring ESL students. In the case of Joe and Lily, Joe held on to his role as a “collaborator” rather than negotiating with Lily in a way that made her more comfortable with her piece of writing. Joe’s limited success in his attempts to transition from grammatical concerns to organization and content concerns could also be attributed to instances where his efforts to understand cultural differences between Lily and himself deteriorated the flow of the conversation and made Lily feel uncomfortable. Powers notes that because a native speaking tutor likely does not know very much about the ESL student’s Furfaro, 14 background or culture, the tutor should be direct and “teach writing as an academic subject” (374). Powers says it is easier to assist ESL writers, “only if we understand what they bring to the writing center conference and allow that perspective to determine our conferencing strategies,” (374). In the case of Lily and Joe’s conference, Joe’s attempts to “understand” Lily’s culture conflate his genuine interest in her background with inappropriately personal questions and combative suggestions that shut their conversation down: Lily: Yeah, it’s not always indirect. And often direct communication [in my family] is considered rude or not respectful. Joe: So why do you think this is something that’s cultural, because my family is not very good at communicating and I’m from Massachusetts. Lily: That’s true. Joe: So I’m not saying that you are wrong, but I want to hear a little more about why you think this is cultural because I think would be interesting about your particular experience. Are you first generation? Were you born here? Lily: I came here when I was ten. In this episode, Joe asked deeply personal questions considering he has never worked with Lily prior to this conference. In the above episode Lily and Joe quickly moved on from the cultural comparison Joe brought up; after Lily divulged her personal information she seemed to retreat from Joe’s invasive questioning which had the effect of shutting down their conversation on issues relevant to the content of her paper. Joe seemed to try to fit Lily into the mold of a native speaker and failed to adjust his strategies to fit her needs. Powers says it is the tutor’s attempt to apply collaborative or other techniques that help native speakers succeed to ESL students that creates the “possibility of cultural miscommunication and failed conferences Furfaro, 15 inherent in the methodology itself” (375). It is likely that Joe was trying to find a way to connect on a cultural basis with Lily. His questions do not seem rudely intrusive; however, the combination of Joe shutting down Lily’s grammatical needs and his overly personal questions led to the miscommunication Powers describes. It is unlikely Joe’s personal questions were motivated by any other agenda than him wanting to get Lily to open up about her paper topic. Despite this, Joe’s method seemed to backfire based on how Lily seemed to remove herself from the rest of their conversation. This sort of miscommunication helps me conclude that it is possibly the combination of Joe’s inherent lack of cultural knowledge about Lily in addition to his blanket application of methods typically used for native speakers that made their conference less successful than it could have been. Case Two: Dave and Jen Jen, a non-native speaker, met with Dave, also a non-native speaker, at the UWMadison writing center to discuss a paper she wrote for a geography course. Jen and Dave met previously to discuss another paper Jen wrote for the same geography course. It is important to note that both Jen and Dave speak Mandarin and Taiwanese fluently. Using the coding system I discussed in the methodology section, I coded the transcript for the writing conference between Dave and Jen, noting trends I found along the way. Three primary trends emerged based on the coding. First, Dave asked three times as many questions as Jen. Second, Jen was three times more explanatory than Dave (took more “turns”). Finally, Dave and Jen negotiated meaning almost the exact same number of times. Furfaro, 16 Discourse Distribution Data TN IN Q M R I L B T Dave 71% 0% 76% 49% 75% 57% 50% 50% 25% Jen 29% 0% 24% 51% 25% 43% 50% 50% 75% For the purpose of my study, the most important trend I investigated was the “negotiation of meaning” between Jen and Dave. As I stated earlier, “negotiating meaning” includes confirmation checks, comprehension checks and clarification requests (see full definition under the sub section titled Case One: Joe and Lily). Unlike the case of Joe and Lily, negotiating meaning between Jen and Dave not only included grammatical negotiation, but also content negotiation. This is an important distinction because it could be argued that because Joe did not adequately negotiate meaning with Lily on grammatical issues, the pair was never able to successfully negotiate meaning on higher order concerns. In the case of Jen and Dave the “negotiation of meaning” is worth splitting into two subcategories: the first category, grammatical meaning, will refer to instances when Jen and Dave worked together to clarify one of Jen’s grammatical concerns. The second category, content-based meaning, will refer to instances when Jen and Dave worked together to clarify points Jen made in her paper (this happened often because her paper was about humanistic geography, a topic her tutor was not particularly familiar with). Throughout the conference Jen initiated negotiation of grammatical meaning by noting specific areas in her paper where she was unsure how to use a particular verb Furfaro, 17 form or how to pluralize a noun. Jen used a more formalistic approach than Lily when she indicated she needed help from her tutor. Dave responded in a formalistic manner. In one episode, Dave explains how to use the word “until” in a sentence: Jen: I am trying to link the sentence with only a phrase. Dave: After “until” you can write… Jen: Which preposition can I use? Or just make a noun… Dave: You mean after a preposition there must be a noun? In, on, at, off… Jen: If I just want to use a preposition… Dave: Yes you can. But usually after “until” you have “what time” … until tomorrow, until December. You want to show particular times. So when you hear “emerges” mark the specific time here. Through negotiation, the pair discussed Jen’s misunderstanding of the correct way to use the word “until.” Jen asks the correct way to use a preposition in conjunction with a noun and Dave helps move her through the process. This episode does not consist of one question asked by Jen and a definitive answer given by Dave; rather, the pair work through exactly what Jen is asking and Dave formally teaches her a skill she can use in the future. Harris and Silva acknowledge that ESL students often use a rule-based approach when writing in English. The way Jen structures her grammatical questions seems representative of the rule-based approach Harris and Silva describe. However, unlike Harris and Silva’s advice to only attend to higher order issues, Dave seems to proscribe more to Power’s strategies; Dave takes on the role of an “informant” when Jen has grammatical questions rather than shying away from her supposed “lower order” concerns. He tells Jen in a direct way how to use the word “until” by stating that “until” must be followed by a specific time. Furfaro, 18 Based on the scope of my research it is unknown how Dave initially learned English and how he was taught to tutor students in the field of writing. However, the way he taught Jen provides some insight on his understanding of Jen’s formalistic approach (one a native speaker would unlikely use). It is possible that Dave was able to successfully negotiate grammatical meaning with Jen because he understood her inherent difficulties with grammar based on his own potential challenges learning English as a non-native speaker. Because Dave’s English training background is unclear I am unable to conclude he did indeed have more background in formalistic English than Joe. But, the way he approached Jen’s grammatical concerns could be indicative of the way he was taught English, which would likely be more formalistic in nature than the way native speakers are taught. Jen and Dave’s progression to higher order concerns was not linear; rather, what made their conference successful was the pairs ability to fluidly transition between Jen’s grammatical concerns and her content concerns. Content-based negotiation seemed to go hand in hand with grammatical negotiation during their conference. This is demonstrated by Jen and Dave’s continual conversation of both higher and lower order concerns throughout the meeting. Jen didn't ask to first address grammatical errors and then move on to content questions; instead, when she felt uncomfortable with her own word choice or had a usage error she asked for Dave’s advice and then easily seemed to slip back into discussion about her paper topic (humanistic geography): Dave: It’s very interesting. The focus of man begins in geographical schools. From humanistic geography and… Furfaro, 19 Jen: Yes, two focuses. Dave: “Two” focus. Foci. Jen: Foci? Dave: Mhm. Jen: Actually, they didn't separate the men and the world. They believed the world is… Dave: Part of the world… Jen: Is generated from the men. How do men…? Dave: See the world. Jen: Mhm. Think, feel, recognize. This episode demonstrates how Jen and Dave’s conversation doesn't devolve into only discussion on lower order concerns when one came up. It also shows the interconnectivity between the content of an idea and how that idea is communicated in English. Dave corrects Jen’s incorrect pluralized version of “focus” but doesn't harp on the issue. After Jen seems to understand Dave’s correction the pair move on to the content they were in the midst of discussing. Dave and Joe’s approaches to addressing grammar exhibit some obvious differences. The way Dave helped Jen when she had a concern was direct and explicit while Joe used collaborative techniques to bypass grammatical errors. Instead of trying to fit Jen into the mold of a native speaking tutee, Dave was able to “collaborate” with Jen in a different sense of the word by working through grammar issues and content issues simultaneously. Based on Celce-Murcia’s research and what I witnessed in Dave and Jen’s conference, I deem this second writing conference more successful than the conference between Lily and Joe. Furfaro, 20 Jen and Dave’s conference took an unexpected turn that could help explain why their conference was able to succeed in the way it did. Because Jen and Dave are fluent in two of the same Asian languages, Mandarin Chinese and Taiwanese, they were able to negotiate meaning without the language barrier Lily and Joe faced. Throughout the conference Jen and Dave’s shared languages and possibly similar background experiences allowed them to negotiate in a way Lily and Joe never could. In one instance, their negotiation helped Jen learn a word in English she did not previously know: Jen: The difference between these two terms. Because place is linking to a personal feeling. Your emotions. Space is more neutralized. The space is trying to link to prior schools of thought that talk about … how do you say … [Chinese] Dave: Oh, ok. Mathematical? Jen: Mathematical. A physical space. In another instance, Jen expressed a word she knew how to say in Mandarin Chinese and then attempted to express it in English. Dave was able to correct her based on their shared understanding of the Mandarin Chinese word Jen expressed: Jen: Because humanistic geography talks about men, I will deal with men. But that is a different viewpoint. Bu you know… Dave: You can use Chinese. Jen: [Chinese] that might be focused on psychology, but here they care more about special behaviors. It is expectful…? Dave: It is predictable? Jen: Expectful? Dave: Predictable. The shared understanding Powers describes (note when I previously mentioned Power’s argument about how understanding the tutees perspective determines a tutors conferencing strategies) is evident in the case of Jen and Dave. They are able to Furfaro, 21 literally negotiate the meaning of various words through the use of more than one shared language, and, this negotiation allowed them to successfully address “higher order concerns” more efficiently. Although their ability to negotiate in multiple languages in itself is not what deems this conference successful, this ability did seem to aid the Dave and Jen’s when they addressed both higher and lower order concerns. Concluding Analysis: The successfulness of the observed conferences was ultimately based on both the level of direct grammatical instruction the tutor was willing to provide as well as the ability of the tutor and tutee to work either within or outside similarly situated cultural frameworks. This second contributing factor, cultural communication, was not immediately evident as a meaningful point of analysis or lens of comparison. However, the cultural differences in Joe and Lily’s conference and the cultural compatibility witnessed in Dave and Jen’s conference made it necessary to evaluate the success of the conferences in light of the trends I saw. Ultimately, the success of the conferences was determined by the ability of the pair to move from lower order concerns to higher order concerns while keeping in mind the specific expressed needs of the individual tutee. This criterion, which seems to be intimately related to cultural communication or a lack thereof, deems Dave and Jen’s conference more successful than the first conference. I think other research could be done evaluating the transcript codes I didn't focus on in this study. For example, the number of questions each individual asked and the types of questions asked would likely include interesting data that could be used to Furfaro, 22 support an argument about the power relations in ESL student conferences. The number of times each individual nominated a topic (another code I used) could also be used to look at the roles of tutors versus their ESL students. This study reveals tensions in native speaking tutor – ESL tutee conferences. However, the small scope of these observations begs for more research to help confirm or deny trends found in this particular study. It is possible that the case of Joe and Lily is highly unrepresentative of the successfulness in most native speaking tutor – ESL tutee conferences. Because of this, more research replicating the methods of this study is needed. Although there is some research on foreign language writing centers, how culture influences writing conferences and the effectiveness of using grammar to teach writing to ESL students, my secondary source research indicates little research has been done studying the techniques of ESL tutors with ESL tutees. Although the institution of ESL tutor based writing centers is somewhat unrealistic, my research provides support for recruiting ESL English graduate students to teach in writing centers at minimum. Furfaro, 23 Bibliography Bruce, Shanti, and Ben Rafoth. ESL Writers: A Guide for Writing Center Tutors. Portsmouth: Boynton/Cook, NH. Print. Celce-Murcia, Marianne. "Grammar Pedagogy in Second and Foreign Language Teaching." TESOL Quarterly 25.3 (1991): 459-80. JSTOR. Web. 10 Oct. 2009. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/3586980>. Goldstein, Lynn, and Susan Conrad. "Student Input and Negotiation of Meaning in ESL Writing Conferences." TESOL Quarterly 24.3 (1990): 443-60. JSTOR. Web. 15 Oct. 2009. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/3587229>. Harris, Muriel, and Tony Silva. "Tutoring ESL Students: Issues and Options." College Composition and Communication 44.4 (1993): 525-37. JSTOR. Web. 20 Oct. 2009. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/358388>. Powers, Judith. "Rethinking Writing Center Conferencing Strategies for the ESL Writer." The Writing Center Journal 13.2 (1993): 39-47. Print. Weigle, Sara, and Gayle Nelson. "Novice tutors and their ESL tutees: Three case studies of tutor roles and perceptions of tutorial success." Journal of Second Language Writing 13 (2004): 203-25. JSTOR. Web. 20 Oct. 2009. Williams, Jessica, and Carol Severino. "The writing center and second language writers." Journal of Second Language Writing 13 (2004): 165-72. JSTOR. Web. 20 Oct. 2009. Williams, Jessica. "Tutoring and revision: Second language writers in the writing center." Journal of Second Language Writing 13 (2004): 173-201. JSTOR. Web. 20 Oct. 2009. Zamel, Vivian. "Strangers in Academia: The Experiences of Faculty and ESL Students across the Curriculum." College Composition and Communication 46.4 (1995): 506-21. JSTOR. Web. 15 Oct. 2009. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/358325>.