Using Data to Support Teachers` Accommodation Decision Making

advertisement

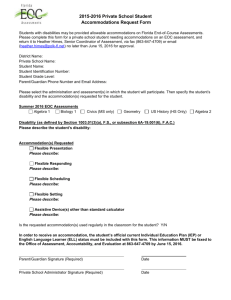

Using Data to Support Teachers’ Accommodation Decision Making Leanne R. Ketterlin-Geller Southern Methodist University lkgeller@smu.edu Lindy Crawford Texas Christian University Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association New Orleans, Louisiana 2011 DRAFT – DRAFT – DRAFT NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION OR REPRINT WITHOUT PERMISSION Researchers studying the accuracy of teachers’ accommodation decision making have found inconsistencies between teachers’ assignment of accommodations and those that students actually need (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2001; Fuchs, Fuchs, Eaton, Hamlett, Binkley, & Crouch, 2000; Ketterlin-Geller, Alonzo, Braun-Monegan, & Tindal, 2007). As a result, considerable variability exists in accommodation assignment procedures, and ultimately, the use of accommodations for individual students. Such variability may compromise the validity of inferences about students’ knowledge and skills in the targeted domain. Studies on the accuracy of teachers’ decisions about accommodations assignment suggests that teachers tend to assign more accommodations than are actually needed by the student. Fuchs and Fuchs (2001) summarized a series of studies comparing teacher assignments of accommodations to measures of the degree to which students benefit from particular accommodations including extended time, large print, read aloud, and calculator use. Students’ performance on accommodated tests was compared to their performance on non-accommodated tests to determine the differential boost in scores caused by implementing each accommodation. They found that teachers tend to assign accommodations to a larger number of students than may actually benefit from them. In a study with 16 4th- and 31 5th-grade students and their teachers, Fuchs, Fuchs, Eaton, Hamlett, Binkley, and Crouch (2000) found that students for whom teachers had assigned accommodations did not experience a greater boost in scores than students for whom teachers had not assigned accommodations. Additionally, these researchers administered a series of basic skills tests to determine students’ potential skill deficits. Using the results of these basic skills measures as criteria for assigning accommodations, they found that teachers awarded 73% of the students with accommodations as compared to 41% when using student performance data as a criterion. As a result, the authors identified student performance data on basic skills tests as a possible mechanism for supplementing and enhancing teacher judgments about accommodation assignment. Similarly, in a study conducted with 3rd graders, Ketterlin-Geller, Alonzo, BraunMonegan, and Tindal (2007) found inconsistencies between the accommodations listed on the students’ IEP and teachers’ recommendations for accommodations in mathematics. In most cases, teachers over assigned frequently administered accommodations such as reading text aloud, extended time, and simplifying text. When compared to recommendations based on student performance data including results from basic skills tests, teachers similarly recommended more accommodations than student performance might warrant. Combined, findings from these studies suggest that student performance data may be a viable tool for improving accommodation assignment procedures. In this paper, we describe an approach to making accommodation decisions using data that is readily available to teachers and IEP teams. We describe the use and potential role student performance data for assigning accommodations as well as perceptions of students’ need based on teacher and parent observations. We also discuss the value of student preferences when assigning accommodations. By systematically incorporating both objective and subjective sources of data, IEP teams can make informed and justifiable decisions about accommodations. Using Data to Make Accommodation Decisions On a daily basis, many different types of data are collected about students’ academic achievement, progress in meeting instructional goals, perceptions and preferences, and behavior. By gathering data from new and existing sources, IEP team member can form a comprehensive data inventory for making accommodation assignment decisions. With a systematic approach, DRAFT – DRAFT – DRAFT NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION OR REPRINT WITHOUT PERMISSION diverse sources of objective and subjective data can help provide the IEP team with a sound basis for accommodation decisions. Objective data sources Teachers and schools amass large amounts of objective data about students. Office referrals, attendance rate, achievement test scores, and number of homework assignments completed are just a few of the objective data sources that are frequently collected. These data can often be tallied, the mean and standard deviation calculated, and results compared over time. Because these data are collected using systematic and standardized procedures, the type and quality of the information is typically consistent regardless of when it is collected, by whom, or using which forms. These sources provide a stable basis for making accommodation decisions. Two common types of objective data that can be used for making accommodation assignment decisions are results from standardized large-scale assessments and results from curriculum-based measurements (CBM). Large-scale assessments such as statewide accountability tests can provide information about students’ general strengths and weaknesses in the domain. For IEP teams, this information is likely to be more useful for determining students’ present level of performance than for identifying which accommodations may be beneficial. However, subscores such as comprehension levels on reading tests and computation skills on math tests can provide useful information about which areas within the larger domains of reading and mathematics might be problematic. For example, a student who performs poorly on the math computation subtest may have difficulty applying basic math facts. This student might benefit from using a calculator on applications problems. Similarly, a student who performs poorly on a literal comprehension test may have difficulty retaining story information in working memory. This student might benefit from segmenting the text into smaller sections and responding to comprehension questions during the reading process. Alternatively, this student may benefit from training in using a graphic organizer to keep track of story information. On a cautionary note: Because subscores are based on a small number of items, they may not be reliable for making decisions about an individual’s specific needs. Data from other objective sources such as CBMs can be used to verify the results from large-scale assessments. CBMs are brief standardized tests that are easy to administer and score, and provide reliable results for decision making. CBMs have been developed in the areas of writing and spelling, reading fluency and comprehension, and math computation and applications. Data from each measure can help identify students’ skills and possible accommodation needs. Figure 1 provides a listing of possible accommodations that may be considered based on CBM data. <Insert Figure 1> Poor performance on a CBM does not necessarily indicate a need for an accommodation. Results from these tests may also help identify areas in which the student needs additional instruction and an accommodation alone may not improve the sutdent’s performance. Subjective data sources can provide important perspectives on, and further inform, data from objective sources. Subjective data sources Subjective data sources include perceptions, preferences, and opinions from teachers, parents, and students. These data may provide valuable insights needed to interpret objective student performance data for making accommodations decisions. Subjective data can bee useful for interpreting the findings from performance tests and exploring the underlying causes of poor performance. The perceptions, preferences, and opinions of teachers, parents, and students can DRAFT – DRAFT – DRAFT NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION OR REPRINT WITHOUT PERMISSION raise ideas not found in objective data, or help link the objective data to the need for specific accommodations. Types of subjective data that are useful for making accommodations decisions include perceptions of students’ skills across the curriculum, preferences for activities students enjoy engaging in, instructional supports that might be beneficial for the student, and the ease or difficulty of typical school-related tasks. These data may point to the potential benefit of an accommodation for a student. Additional information about the frequency of accommodations use can be asked to determine what accommodations are already implemented in instruction. Such data, when collected from the various members of the IEP team, can be aggregated to evaluate similarities and differences between the reports of the IEP team members. Along with the objective data, this information provides a profile of the student’s strengths and weaknesses that can be informative for making accommodation decisions. Figure 2 illustrates a sampling of possible survey questions represented in a summary report that indicates the level of agreement across sources and provides possible recommendations for accommodations. Input from the special education teacher, general education teacher, parent, and student are collected. The summary judgment provides the mode of the scores to indicate the rating most often received. In instances where there is discrepancy of more than one point across raters, a check mark is placed in the column labeled “Topic for Discussion.” These disagreements can be discussed in detail at the IEP team meeting. The column labeled “Accommodation to Consider” lists possible accommodations that may benefit a student for whom the activities are difficult or very difficult. <Insert Figure 2> Systematic data collection using a survey such as the one presented here elicits responses from multiple IEP team members on similar questions of student strengths and needs. The data are subjective, but focused on common questions directly relating to a student’s potential need for accommodations. Frequently updating and checking perceptions can help avoid confirmation biases that might arise when teachers, parents, and even students have outdated perceptions of need. Also, by completing the surveys separately, different members of the IEP team can provide their input without inadvertent influence from other members of the team. For example, students may defer to their parents or teachers about what instructional supports would be helpful. The perceptions gathered on a survey of this kind can then be compared and discussed among IEP team members to arrive at points of strong agreement on the student’s potential need for accommodations. The subjective data can then be compared with objective data sources, in a deliberate process, to inform the accommodation decisions of the IEP team. Conclusions In this article, we described the importance of using a variety of information to make accommodations decisions. We defined objective and subjective data sources and provided examples of the types of information that can be collected. We presented a list of possible accommodations to consider when evaluating objective performance to determine which accommodations may be beneficial. Additionally, we illustrated a method for collecting and displaying subjective data that directly relates to the potential need for accommodations (systematically reports perceptions from different stakeholders). No current system exists that can reliably determine a definite need for an accommodation. IEP team members must currently work with what tools and data are available, and what additional data can be collected with their limited time and resources. Having, and not having, appropriate accommodations may be the key to academic and social success for some students, and accommodations decisions should be DRAFT – DRAFT – DRAFT NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION OR REPRINT WITHOUT PERMISSION made through a systematic process, using the most relevant data available. Until a more comprehensive and reliable system exists for making accommodations decisions, IEP team members can work to gather reliable, objective data, and focused perceptions of the student’s unique strengths and needs, in order to make the best possible accommodations decisions. By providing this information, we hope that IEP teams have a mechanism for integrating objective and subjective data and can use this information to make appropriate accommodation assignment decisions to support student learning. DRAFT – DRAFT – DRAFT NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION OR REPRINT WITHOUT PERMISSION Figure 1. Using Objective Data to Guide Accommodation Decisions Tested Domains Possible Reasons for Poor Accommodations to Consider Performance Writing and spelling Poor letter-sound Allow student to respond to questions correspondence in alternate formats such as typing, pointing, with the use of a scribe, or Poor text organizational other assistive devices skills Graphic organizer Poor fine motor skills Provide extended time to allow for proof reading and editing Increase space for constructed responses or increase size of bubbles for multiple-choice items Allow students to mark answers in test book Allow student to use a spelling dictionary or spell check Reading fluency and Limited fluency with Simplify the language of all materials comprehension decoding Read printed materials aloud Poor pre-decoding Administer tests in a separate location skills such as phonemic to allow student to read material aloud segmenting and Graphic organizer blending Allow student to highlight key words Poor text organizational or phrases skills Math computation Limited fluency with Provide a calculator or arithmetic and application math facts tables Poor spatial recognition Provide protractors, models, or skills manipulatives DRAFT – DRAFT – DRAFT NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION OR REPRINT WITHOUT PERMISSION Figure 2. Using Subjective Data to Guide Accommodation Decisions Accommodations Survey Zachary Robyns Grade: 3 Teacher: Ms. Perry Student ID: 7351 Summary of Proficiency in Academic Domains Alex’s skills were rated on a 4-point scale. A score of 1 meant “not proficient” and 4 meant “highly proficient.” Proficiency Teacher 1 Teacher 2 Student Parent Summary Topic for Judgment Discussion Reading skills 2 2 3 2 Emerging Proficiency Writing skills 3 2 3 1 Proficient * Math word problem solving skills 2 1 2 1 Not/emerging proficiency Summary of Potential Benefit of Instructional Supports The potential benefit of the following instructional supports for Alex was rated on a 4-point scale. A score of 1 meant “not helpful” and 4 meant “really helpful.” Teacher 1 Teacher 2 Student Parent Summary Topic for Judgment Discussion Use a calculator to solve math 4 3 1 3 * Helpful problems Use models or objects 3 3 2 3 Helpful (manipulatives) to solve math problems Summary of Difficulty Completing School Related Tasks The difficulty Alex faces when completing school-related tasks was evaluated on a 4-point scale. A score of 1 point meant the task was “not difficult” and a score of 4 meant the task was “very difficult.” Teacher 1 Teacher 2 Student Parent Summary Topic for Accommodation Judgment Discussion to consider Complete a test within the 2 2 1 2 Somewhat Extra time allowed amount of time difficult DRAFT – DRAFT – DRAFT NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION OR REPRINT WITHOUT PERMISSION Read and understand written directions Work independently for 45-60 minutes Understand the meaning of words in word problems 3 4 2 4 Difficult 2 3 2 2 4 3 3 4 Somewhat difficult Difficult/ Very difficult Take a test in a room with other people or distractions 2 1 1 2 * Not/some what difficult DRAFT – DRAFT – DRAFT NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION OR REPRINT WITHOUT PERMISSION Read aloud Multiple short testing sessions Simplify language in problems and directions Allow student to work alone in a separate testing location Author Note We would like to thank Magaly Gonzales, Kyle Hoelscher, and Gerald Tindal from the University of Oregon for support on the initial discussions of these ideas. DRAFT – DRAFT – DRAFT NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION OR REPRINT WITHOUT PERMISSION