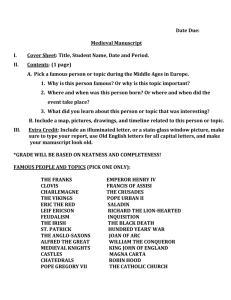

Part 2: ChV MSS [The Chastelaine de Vergi manuscripts

Part1. Introduction

1. Rachel: Introduction

[check projector] [smile]

Good morning. Hannah and I are here to talk about our research project: The Dynamics of the

Medieval Manuscript: Text Collections from a European Perspective. We want to increase awareness of our project and open our work up for discussion, so we very much look forward to your questions.

We’re doing a joint introduction on the project, and then we’ll each present some individual research. The project is a collaborative work between the universities of Bristol [point at logos on powerpoint], Utrecht, Vienna and our university, King’s College London. It is a three-year project, and we are a little over halfway through the first year. We have been lucky enough to obtain funding from the HERA Joint Research Programme and the European Community.

So, I would like to start by exploring the title of the project: The Dynamics of the Medieval

Manuscript: Text Collections from a European Perspective. Hannah is going to discuss the issues of terminology that lie behind the phrase “Text Collections”, and I will then discuss the collaborative, pan-European nature of the project in more detail.

But for now, I want to talk about the phrase “The Dynamics of the Medieval Manuscript.” This might strike some people as a little too abstract, perhaps. [grin] And yet, we are using this phrase as a way to look at real, observable phenomena of medieval textuality. What we mean by dynamics is the movement and change of meaning that occurs when a text is copied into varying contexts and read alongside a variety of other texts. We want to look at precisely this phenomenon in depth and in relation to short narratives.

Now over to Hannah.

[sit down]

2. Hannah: Issues of terminology

Thank you Rachel.

Our project focuses on manuscripts dating from the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries, containing short verse narrative texts. The short verse narrative is a highly mobile form. It migrates easily from

1

codex to codex, and rarely appears in single-item manuscripts. It can range in genre from the courtly lai, to saints’ lives and fabliaux. Indeed, the generic boundaries often overlap, and it is this generic fluidity which facilitates the integration of the short tales into diverse manuscript contexts. It is the variety and potential of each new contextualisation which makes this such an exciting project. The notion of short narrative has different connotations and relevance in each linguistic region of our project. For example, the English team will be focussing on the short Middle English romance, of approximately 2000 lines, whereas the German team will be looking at Mären, non-generically bound short narratives.

When we approach the manuscripts, it is important for us not to project what we want to find.

Rather, our goal is to investigate textual and physical evidence in order to explore the principles of organisation underlying manuscript composition. Indeed, this influences our conceptual framework, how we approach the issue of terminology and the taxonomy of the medieval book. The perception of a manuscript can be affected by whether a multi-text codex is defined as a miscellany or anthology. The inconsistent appropriations of the terms miscellany and anthology in Anglophone criticism proves to be an ongoing contentious issue. It has been much discussed by Theo Stemmler,

Carter Revard and most broadly in the illuminating collection The Whole Book.

[YOU WILL BE ABLE TO FIND ALL OF THE REFERENCES ON THE HANDOUT]

The use of the term ‘miscellany’ has been adopted to describe the haphazard arrangement and accumulation of texts, more neutrally as a codex containing diverse content, and it has even been appropriated as a synonym for ‘anthology’. ‘Anthology’ is generally linked to ideas of careful arrangement, yet also it may be used to describe quite different forms.

The nuances of our own concepts of medieval manuscripts and the labels that we use to describe them will be developed as our research progresses. On our project website, miscellany is interchangeable with text collection, to refer neutrally to manuscripts containing multiple texts.

The history and production of a codex has an important bearing on our investigations. For example, an organic manuscript, made in a single process, perhaps by 1 or 2 scribes, would offer a potentially different reading experience from a composite manuscript, made up of originally discrete units, bound together at a later date. Even if the textual content appears to be similar, the physical makeup and presentation of material affects the reception of the whole and what we perceive as principles of organisation. This is why we cannot rely on library catalogues alone.

3. Rachel: Pan-European nature of the project

[smile at Hannah] [stand up] [check projector] [smile at audience]

2

I am now going to talk about the pan-European nature of the project. Together with Karen Pratt, our supervisor, Hannah and I represent that part of the project that is looking at medieval French literature in its manuscript context. The project also has a team working on medieval English literature, based at Bristol University; a team working on medieval Dutch literature, based at Utrecht

University, and a team working on medieval German literature, based at the University of Vienna.

We also have several eminent advisors. You will find all the names and email addresses on our handout.

It is really good for us that we aren’t all working in isolation; especially since the objects of our study did not exist in complete isolation from each other. Some of the manuscripts containing medieval

French literature, for example, were, in fact, produced in the British Isles, and many of the actual texts were originally composed in Anglo-Norman French. Likewise, I understand there is a certain amount of geographical overlap between some of the Dutch and German manuscripts, and many of our manuscripts are, in fact, bi- or tri-lingual. We even have stories in common between the different literatures: the Chastelaine de Vergy, for instance, was translated from French into Dutch, and various Latin texts were translated into several vernaculars.

As such, it is a tremendous advantage for us all to be able to benefit from each other’s perspectives.

In our initial project meeting at Utrecht, for example, it transpired that the idea of long compilation manuscripts containing “dyads”, paired texts with a close relationship to each other, is much more of a commonplace in the criticism of German material than it is in criticism of French material, and, having been introduced to this concept, I can now look out for it in the French material, and it may well end up being a fruitful site of comparison.

[hand over to Hannah]

4. Hannah: French Project

Scholars of medieval French literature have been rediscovering texts in their manuscript context over the last 20 years, most notably the pioneering work of Sylvia Huot and Keith Busby. Most recently, a Swiss research project called “Hypercodex”, investigated manuscript collections of diverse content and organic composition, including both short and long narrative texts, and containing at least 25 works in total. Their period of investigation was defined by the manuscript corpus, the majority being created between the mid thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. We would like to develop the field further by specifically focussing on the short verse narrative and its

3

manuscript transmission and by taking a pan-European approach. Our research on the French miscellanies is divided into two interrelated projects. The first follows the evolving manuscript transmission of a single short text, La Chastelaine de Vergi. The second takes a broader approach, investigating Anglo-Norman and Continental French miscellanies more generally.

Through our research we hope to engage with the compelling issue of the principles of organisation governing manuscript compilations and the moment of cultural and literary history inscribed within them.

So what are we investigating? [powerpoint slide with 3 big questions – 15 seconds?]

These are just some of the issues that we hope to investigate, both locally, and globally, in relation to the organisation of the manuscript as a whole. We hope to combine in depth codicological and paleaographical analysis with literary criticism, in addition to relevant theoretical approaches.

[HANDOVER:] And now Rachel is going to talk about her individual project.

Part 2: ChV MSS [The Chastelaine de Vergi manuscripts: context, genre and coherence, with particular reference to français 837]

Thanks, Hannah.

The manuscripts containing the short narrative La Chastelaine de Vergi are utterly fascinating in their own right; they are also highly representative of medieval French textuality overall. The corpus comprises some twenty medieval manuscripts (and two eighteenth-century copies), ranging from relatively obscure manuscripts to some of the most famous ones in existence, such as Hamilton 257 and français 837, which you will see listed on the handout. Moreover, while all the Chastelaine manuscripts fit the definition of “multiple text manuscript”, they do vary somewhat. Six out of twenty manuscripts have only two texts, and four of these contain only the Chastelaine de Vergi and the Roman de la Rose. At the other end of the scale, français 837 has 251 texts.

As many scholars such as Keith Busby and Sylvia Huot have pointed out, the context in which a text occurs has implications for how that text is read, including in terms of genre. The Chastelaine de

Vergi is particularly interesting in this respect, since it has a variety of diverse elements which might be read as pertaining to different genres. It is commonly thought of as a short courtly narrative, and so when it is put with other short courtly narratives in modern anthologies, it seems to fit in well; it

4

also has a strong didactic element, and so would seem like a didactic text if placed with other didactic texts; it also has a female villain who behaves rather like a fabliau woman, or, indeed, the way that misogynist diatribes claim women behave.

Looking at the catalogue entries, there are two manuscripts which seem to have a particularly clear theme which foregrounds one aspect of the Chastelaine de Vergi. Français 780 contains mainly nonfictional, vaguely historical texts, which seem to share a certain interest in upholding the “right” order of things, and this suggests the Chastelaine was being read as historical truth and /or a negative moral exemplum. Valenciennes 417, in the words of Sylvia Huot, is composed of texts

“addressing the fortunes and misfortunes of love and the ethical questions raised thereby”. The reader is thus encouraged to see the Chastelaine first and foremost as a love story – and also to ask questions about the ethics of the situations the characters find themselves in.

However, some of the Chastelaine manuscripts are far more united in theme and genre than others, and at this stage, I strongly suspect that the majority of them are far too disparate to favour one single reading of the Chastelaine to the exclusion of all others; I think the effect of the context on the text may well prove more complicated.

Genre is, of course, a highly contentious issue for medieval literature, one where a certain amount of caution is advisory. My views on genre are very much shaped by Jauss: that texts contain allusions to recognisable paradigms which interact with and shape the reader’s horizon of expectations. I am also following Riffaterre in that I am interested in how this process of interaction and recognition beween reader and text happens line by line.

[change slide]

This is taken from français 837. I think it is particularly appropriate to apply these concepts on genre to this manuscript, since the original layout had explicits following the texts, but no incipits preceding them. You can see the explicits are in the scribal hand, and the incipits are in a different hand, much later, late fourteenth or early fifteenth century. Prior to that addition, someone reading one of the texts for the first time would be starting without a title to shape their expectations, and would have to build their own idea of what kind of text it was as they read.

Now let’s move on to a concrete example of how this works in practice. Two genres which have a certain amount in common are prayers to the Virgin Mary and love discourses (saluts, requestes and

5

complaintes d’amour, and other texts sharing similarities with them). I went through français 837 trying to see what it is that makes a love discourse different from a marian prayer, and what kinds of signals are used to mark that divergence.

I found that there were a number of very clear signals whereby the texts display their affilations.

Even thematic similarities between the different kinds of text, such as the intimation that the speaker is ill and the female addressee can cure him, are treated very differently. Moreover, the texts are densely peppered with these signals, such that it does not take the reader long to work out which overall category an individual text belongs to.

Some texts in the manuscript were obvious from the first couplet, and it was extremely rare for there to be any plausible doubt as to a text’s overall affiliations twenty lines into the poem. In the entire manuscript, there is no text whatsoever where the reader can get to the end and still not know whether the object of devotion is earthly or heavenly.

The requeste d’amors you can see here is one which takes a little longer than many to establish its affilations. It begins with a string of complimentary adjectives, “Douce simple cortoise et sage”.

These would be equally applicable to the Virgin Mary or to a real woman. However, over the next few lines, certain elements build up which are more typical of love lyric than prayer, such as sending greetings, sighing, allusions to the speaker’s suffering, and various others. Their effect is cumulative, suggesting that at this stage, it seems more like romantic love than spiritual devotion. Allusions to love-sickness and the sweet rewards of love – here – act as confirmation that that is what it is. All possible ambiguity finally disappears with the allusions to other famous lovers, namely Blanchandin,

Tristan and Cligés. This settles it beyond any doubt that the love is, indeed, romantic love. The explicit merely acts as confirmation “Explicit la requeste damors”.

Of course, I do not deny that some texts contain actual mixed signals. Français 837 contains a prayer to the Virgin Mary which calls her “savoreuse”, a term best translated as “delectable”. The manuscript also contains a love discourse where a church-sanctioned way of referring to the Virgin

Mary, the “stella maris” or “star of the sea” trope, is used to describe the beautiful eyes of a lady from whom the lyric persona would like to obtain sexual favours. Nevertheless, in both cases, the anomalous signal is surrounded by many other, strong signals, all pointing in the same direction, such that the prayer is definitely a real prayer and the requeste d’amours is definitely a love discourse. We are still dealing with different kinds of text; even if the boundaries are a little blurred

6

they are still there. Looking into this has made me confident that it is not a fruitless or pointless endeavour to group texts into categories in order to analyse the contents of the Chastelaine de Vergi manuscripts, as long as I exercise caution and flexibility.

Given the presence of very different texts with very different affiliations (generic and otherwise) in the same manuscript, to what extent can one talk about the manuscript existing as a whole, having coherence? I believe that the use of layout can play a vital role in the creation of coherence, or the impression upon a reader that the book is a whole and the texts are its component parts.

In français 837, there is a very strong sense of coherence given by the almost perfect adherence to a fixed pattern for the layout. The boundary itself is marked by a blank line after the last line of the text itself, then an explicit, then – originally – a blank space of a few lines, then a large dentelle initial at the beginning of the next text. This is more than sufficient as a boundary – it is eye-catching – but it is not a lot, and the addition of incipits by a later scribe adds emphasis to a boundary that was previously much less marked, with the flow from text to text being less interrupted.

Another thing that gives a sense of the book flowing from text to text is the rarity with which a new text starts on a new column, let alone a new page. The scribe was clearly reluctant to do this, making decisions to put a starting initial at the bottom of a column rather than the top of the next one even when that meant it had to be noticeably smaller than such initials elsewhere in order to fit. I believe that this sort of layout favours close reading of the texts against each other far more than when they are, for example, separated by blank leaves, or laid out on the page in a different way so that the passage from one text to another is less smooth.

The close proximity of last and first lines in français 837 creates some fascinating contrasts, as well as parallels between texts. On f.66v, for example, we make an abrupt transition from “Chantons de deus laudamus” to “Molt bons lechierres fu boivins”, passing from pious praise of God to admiring a character for his love of worldly pleasures. Likewise, the boundary on f.51r juxtaposes a last and a first line that mark their respective texts as fabliaux. One text ends “Tout issi cis fabliaus define”. The next begins “Cis fabliaus dist seigneur baron”. The juxtaposition makes it clear that these are the same kind of text, drawing a close link between them.

This is, of course, in addition to the presence of actual dyads within français 837, such as Le Songe

d’Enfer and La voie de Paradis, where a text on heaven seems to have been written as a companion

7

piece to a text on hell, and they appear next to each other. Dyads like these exist, but so do cases where it is the act of compilation, not literary invention, which has created a relationship between texts.

I hope I’ve shown that there is a lot of interesting work still to be done on the Chastelaine de Vergi manuscripts, even on the famous français 837. I’m certainly going to enjoy doing it. I’ll hand over to

Hannah now to talk about her part of the project.

Part 3. Hannah [Frame narratives and Francophone text collections of the 13th and 14th centuries]

The number of French literary collections containing short verse narratives is prolific. Of these manuscripts a significant number also contain frame narratives, such as the Fables of Marie de

France, Le Roman des Sept Sages, Barlaam et Josephat and the two French verse translations of

Disciplina Clericalis by Petrus Alphonsus. These longer texts are made up of short stories, fused together by a narrative frame. Their composition lends them a liminal status, being both made up of short tales yet forming a larger whole, which has evoked comparisons with manuscript compilation in the past. In this paper, I will be exploring the effects of the frame narrative on Francophone text collections, the relationship they set up with neighbouring short verse narratives and the status of the tales within the frames. In addition, I will be looking at how the frame narrative might relate to other frames, such as the emergence of the author corpus in the 13 th century.

The two French verse translations of Disciplina Clericalis appear in a number of francophone text collections. The Norman version A has been identified as Fables Pierre Aufors and the Anglo-Norman version B as Le Chastoiement d’un père a son fils. The pedagogical exchange between father and son forms the frame around the short tales, which are inserted as exempla to illustrate the paternal advice. In the original Latin, the narrator states that it is composed ‘partly from the sayings of wise men and their advice, partly from Arab proverbs, counsels, fables and poems, and partly from bird and animal similes.’ 1 He states that he has deliberately chosen ‘to break up instruction into small sections’ to avoid boredom due to ‘the infirmity of man’s physical nature’.

2 Man’s concentration span here said to favour the short text. In contrast to the Latin original, the vernacular versions show

1 The Disciplina Clericalis of Petrus Alfonsi, p.104

2 Ibid., p.104

8

remarkable levels of variance, each scribe or compiler reworking and reordering the material according to the new manuscript context.

BL, Additional 10289 contains supposedly the oldest extant example of the Fables Pierre Aufors. In the prologue, the narrator emphasises his role in translating the work of Petrus Alphonsus and insists on the ‘sens’, wisdom that his text will bestow [need to look for Latin word]. Yet in keeping close to the ethos of the original, this is teaching with sugared pill, something that will also offer pleasure.

3

Condensing the sources of the original, in the French translator’s prologue, he writes [will check ms tomorrow]: J mist deduiz et bels fableax / De gens de bestes et doiseaux’ (‘Mos sachez quil tua deduit /Que ne fert chargie de boen faire’) [not sure if I’m going to keep the whole quotation]

(f.133va).

It is interesting that the translator uses the term ‘bels fableax’ at this point as opposed to ‘fables’, a more neutral term to refer to tale or story, and elsewhere as the antithesis of truth. ‘fableax’ only appears a handful of times in this version along with the synonym ‘fablel’. Per Nykrog noted this specific usage of ‘fableax’ to designate the three tales on cheating wives. Based on this label and their plot lines, which all fit the sub-category of the amorous triangle, in which the lovers are successful and the husband is outwitted, he justified the inclusion of these tales in his list of fabliaux.

In contrast to Per Nykrog, the editors of the highly influential Nouveau Recueil Complet des Fabliaux

(NRCF) chose not to include these tales. In addition to five tales from the Fables Pierre Aufors, Per

Nykrog also includes two tales belonging to another frame narrative, the Fables of Marie de France, none of which feature in the Nouveau Recueil. Yet, as the following examples illustrate, Per Nykrog’s case for considering the frame tales as fabliaux appears to be convincing.

In the Fables Pierre Aufors of Additional 10289, the father acknowledges the risqué nature of the fabliau-esque tales and shows an awareness that they may not be understood with his same

3 ‘in order to facilitate remembrance of what has been learnt, the pill must be sweetened’, The Disciplina

Clericalis of Petrus Alfonsi, p.104

9

intention (i.e. as negative exempla) in a different context. It is this fictional context that has the effect of neutralising the ‘fableax’ within the ‘didactic’ frame of Fables Pierre Aufors and which facilitates the addition of the fabliau Jouglet at the end of the manuscript. Jouglet also brings to the fore many of the subjects and motifs of the Fables: for example, issues of inheritance, the figure of the mischievous jongleur, the engin of Robin’s wife and her revenge, even Robin’s sheep, and most significantly, the consequences of taking bad advice. Jouglet teaches the young uninitiated Robin: ‘E apreist e ensegnast’ (fol.175vb v.54), words that are echoed throughout the tale. However, in a reversal of the fabliau-esque tales of the Fables, his teaching is undone and it is Robin’s wife’s who enacts his revenge.

In BL, Harley 527, a fabliau is inserted directly into the of Le Chastoiement d’un père a son fils. Le

Cuvier augments the series of tales on unfaithful wives. As another example of the lovers outwitting the cuckold, it is seamlessly absorbed into the frame. Moreover, the narrative context creates the space for the inclusion of the fabliau. In contrast to the anxious father of Additional 10289, this father utters no qualms about recounting the guiles of women to his son. The only other extant version of Le Cuvier appears in français 837. This version is included in the Nouveau Recueil, however

Le Cuvier of Harley 527 is not.

In different example, Petrus Alphonsus’ authorship is extended to a fabliau which does not form part of his literary compilation, nor its French translations. Le Chevalier qui recouvra l’Amour de sa Dame bears the enigmatic signature of ‘Pierres d’Anfol’.

4 Busby argues that this attribution confirms the

‘successful integration’ of the fabliau-esque frame tales into the fabliaux corpus.

5 Indeed, I would argue that this suggests a medieval reception of the frame tales both as independent units and as part of Petrus Alphonsus’ literary compilation, that they might share the same sense of integrity as the fabliaux. [Still thinking about these parts: Another interesting example, of a different genre, is

4 Nykrog, Les Fabliaux, p.35

5 Busby, ‘Beast epic’, p.111

10

the Lai de l’oiselet, a tale said to originate from Disciplina Clericalis. It shows how it is useful to consider tales within narrative frames, frames that could be compared to Genette’s ‘paratexte’.]

Later frame narratives, such as Bocaccio’s Decameron and Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales are said to have been influenced by the diversity and juxtaposition of tales and storytellers in thirteenth- and fourteenth-century manuscript collections. Carter Revard argues that earlier readers were already aware of [QUOTE] ‘how authorial and “dramatic” viewpoints transformed reality’.

6 He compares a sequence of varied texts from Harley 2253 to the original Latin Disciplina Clericalis. However, he does not acknowledge the presence of the French verse translations of the Disciplina Clericalis in the manuscripts which form his argument. Nor does he acknowledge the role that the frame narrative already plays within the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century text collections.

Two of his examples, Digby 86 and français 19152, contain versions of Le Chastoiement d’un père a

son fils. Significantly, the Chastoiement is the first text of 19152, the threshold to the manuscript, and it is also followed by another frame narrative, the Fables by Marie de France. The dynamics of the thematic groups within the Chastoiement have been said to influence the groupings of individual fabliaux throughout français 19152.

7 This is a striking example of how the organisation of a frame narrative can act as a model for the organisation of short verse narratives in a text collection. [May not include: Moreover, a later hand adds short titles in the same manner to the tales of the

Chastoiement and to the individual fabliaux, suggesting a parallel between how the frame tales and the later fabliaux were read. [need to check facsimile] ]

In the trilingual collection Digby 86, another of Carter Revard’s examples, the original scribe rubricates each tale of Le Chastoiement with a title. Le Chastoiement is the first in series of French

6 Revard, Carter, ‘From French ‘fabliaux manuscripts’ and Harley 2253 to the Decameron and Canterbury

Tales.’ p.270

7 Busby, Codex and Context, p.452, footnote 127

11

verse texts and each of the shorter texts that follow is rubricated in the same manner, integrating the frame tales of Le Chastoiement and individual short verse texts into the manuscript context. A sense of local coherence is created in this section of French verse texts [and could be related to the global coherence Rachel highlights in français 837]. By deliberately breaking the frame into its component parts, the scribe is able to integrate both the frame and texts that follow into the manuscript context.

In Arsenal 3142, another frame narrative, the Fables of Marie de France could also be described as having a transitional status. Wagih Azzam and Olivier Collet argue that her text holds a strategic position in this manuscript, assuring the smooth transition from the longer texts that dominate the first half of the manuscript to the series of shorter texts grouped towards the end.

8 Arsenal 3142, is a precocious example of a narrative text collection that foregrounds the figure of the author, including

Adenet le Roi, Alart de Cambrai, Jean Bodel and Marie de France. An illumination featuring the author heads each text [POWERPOINT: here we find the image of Marie that introduces her Fables

Another image of Marie also appears at the end (see Busby).

Interestingly, Marie’s Fables and the series of individual dits by Baudouin de Condé are both presented as homogeneous totalities, with a similar mise en page. There is no illumination of

Baudouin de Condé, however the rubric ‘Ci commencent li dit Baudouin de Condé’ introduces his oeuvre, as `Ci commencent li dit Rustebuef' opens the Rutebeuf section in français 837. In Arsenal

3142, we find the author collection explicitly parallels the narrative frame, a whole made up of constituent parts. Indeed, shared authorship and authoritative voice frames both.

I would like to end by going back to the Fables Pierre Aufors of Additional 10289, to the point where the father expresses his concerns before recounting the three fabliau-esque tales. In the original

Latin version, the emphasis is on the father’s reputation, he is afraid of being considered as immoral

8 Azzam, Wagih, et Olivier Collet, ‘Le manuscrit 3142 de la Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal. Mise en recueil et conscience littéraire au XIII ᵉ siècle’, Cahiers de civilisation médiévale, 44, (2001), 207-245, p.217

12

as the women he will describe. In the translation of 10289, the father’s anxiety is focussed more on what might happen to his spoken story if it is put down in writing, how it might be understood outside the context of his teaching:

‘Filz plusors choses te contasse

De lor engien se je osasse

Mes je vei bien que tu veuz metre

Tot quanque jete di en letre

Si orra tel par aventure

Mes paroles en tel escripture

Qui tot a mal a tornera

Ce que folement dit sera

Por home estruire et doctriner

L’engien que l’autres fait avra

Qui mauvais essample i prendra

‘Son, I would tell you many things

About their cunning if I dared

But I see clearly that you want to put

Everything I tell you down in writing

And so it is possible that somebody might hear

My words put down in writing

And they might turn to an evil purpose

Something which I might have said foolishly

But with the intention of teaching people and instructing them so that they know how to behave better.

And so it would go quite otherwise; for such a person would Et por saveir sei mieuz garder.

Si ira el, quer teus orra hear about

The ingenious ruse that someone else had carried out

And model themselves on it in a bad way

And make another attempt at doing the same thing.

Et autresi ressaiera’

It is in this passage that we find an intriguing expression of the double nature of the frame narrative

(as defined by the ‘Hypercodex’ team) a form which both foregrounds (fictive) oral transmission, and demonstrates the infinite possibilities of recontextualising the material in written form. This anxiety over the passage from the oral to the written, the potential meanings that could be generated by each new contextualisation, has much to do with what is at stake in the act of literary and manuscript compilation. As Rachel has highlighted regarding the Chastelaine de Vergi, the different manuscript contexts offer different readings, interpretations of the text, even without considering textual variance. And here I quote the Hypercodex team: ‘The dynamic of the corpus of inserted fables/tales explicitly magnifies the capacity of writing to offer the possibilities of arrangement and re-arrangement, classification and the organisation of knowledge.’ 9 It is not the instability of oral

9 ‘La dynamique du corpus de fables enchâssées exalte la capacité qu’a l’écriture d’offrir de manière accrue des possibilités d’arrangement et de réarrangement, de classification et d’organisation du savoir.’ Azzam, Wagih,

Olivier Collet et Yasmina Foehr-Janssens, ‘Mise en recueil et fonctionnalités de l'écrit’, Le recueil au Moyen

Âge. Le Moyen Âge central, sous la direction d’Olivier Collet & Yasmina Foehr-Janssens, (Turnhout: Brepols,

2010 )(Texte, Codex & Contexte VIII), pp.11-34, p.33

13

transmission, but the regeneration of meaning that writing offers which renews and refreshes the circulation of short stories in each new context.

Our plan for the next few months includes a research trip to Paris, where we hope to conduct some empirical research at the Bibliothèque National and other libraries. We are also looking forward to our next project meeting in Vienna, and the opportunity to share our research findings with the project team as well as learn about our colleagues’ progress.

Thank you. We are happy to respond to any questions you might have.

14