Feudalism Systems of Japan and England By Rit Nosotro

advertisement

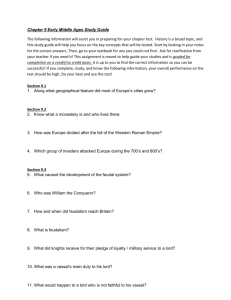

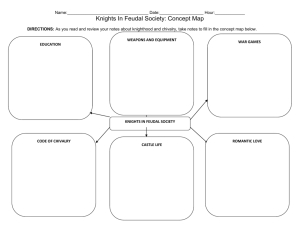

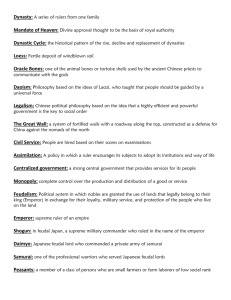

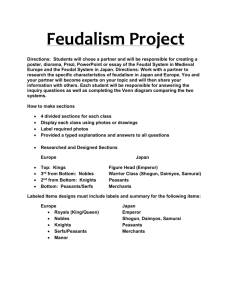

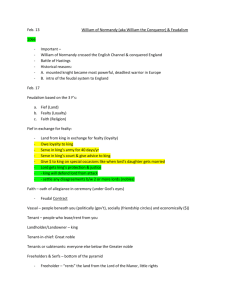

Feudalism Systems of Japan and England By Rit Nosotro Thesis Statement The feudal systems of Japan and England strongly contrasted in the religious justification which organized behavior The English and Japanese feudal systems are similar in that they both gave grants of land for military service, and the social ladders were similar. After that point, they differ. In the English feudal system, to get grants of land one must swear an oath of fealty to one's lord, but in the Japanese system that was not required. The military classes for both feudal systems lived by a code of honor yet with different goals. They had different monetary gains, and the armor they wore was different. Japanese peasants (shiki) had a little more freedom than the English peasants (serfs) because they could own land. Both warrior classes were inspired to fight by religion but differently, the knights for God’s glory and the Samurai for their own. What does the word feudalism even mean? In a broad definition, feudalism is "a system by which the holding of estates in land is made dependent upon an obligation to render military service to the king or feudal superior."1 Both Japanese and English feudal systems were based on the imperative need for a constantly trained and well equipped military, and a method of repayment for these military services. Generally speaking, the feudal superior would provide protection, possibly food, and tenure of land to his subordinates, in return for military services or agricultural remuneration. Contrary to their English counterparts, Japanese lords did not require an oath of fealty from their vassals in return for fiefdoms. Because of not swearing an oath of fealty, Japanese vassals were far less hindered and controlled by their lords.2 Another divergence in the two systems consisted in the different religions and beliefs that drove the knights and samurai to obedience, thereby allowing the systems to function relatively smoothly. Although comparable in the major essences of overall structure, the feudal societies of Japan and England differed greatly in the separate relationships between lord and vassal and the differential motivations of the military subordinates for service. After smashing Saxon resistance in the Battle of Hastings in 1066, William the Conqueror implemented the Frankish system of feudalism in England. In order to maintain control of his English acquisition, William doled out all Anglo-Saxon land to his Norman followers. At the top of his feudal system was himself, the king, who owned all land in England. While the king kept one quarter of the land as his personal property, the church received a percentage, and the rest was leased to trusted noblemen and favorites of the king. Feudal nobility included barons as landlords, while knights supplied consistent military services for their lords. Bound by serfdom to small plots of land, the peasant workforce that provided agricultural labor for landlords was at the bottom of the social, political, and economic ladder.3 In the late twelfth century, a clan leader named Minamoto Yoritomo founded the first Japanese shogunate, a feudal government that lasted for seven hundred years. After defeating a rival Taira clan, Yoritomo was named shogun by the emperor in 1192. Although the emperor remained the virtual ruler of Japanese hierarchy, the shogun controlled the real reins of power as supreme military administrator. Instead of moving to Kyoto, the imperial capital, Yoritomo set up a centralized government and ruled from his field quarters. Thus his feudal government earned the Japanese name, bakufu, or tent government.4 In composing the first primitive feudal society in Japan, Yoritomo paralleled some methods of William the Conqueror. As a practical means of control, Yoritomo rewarded his followers with strategic grants of land. Yet unlike William, Yoritomo did not impose oaths of fealty on landholders. With a social order resembling that of English feudalism, Japanese aristocracy ruled, samurai provided military services, and peasants occupied the lowest rung of the feudalistic ladder. To receive a grant of land, an English nobleman offered homage to his lord on bended knee, demonstrating his obedience and reverence. Swearing faithfulness and military and financial support through the customary oath of fealty, the nobleman knelt and placed his hands between his lord's, thereby becoming his vassal, or baron. In return, the lord swore a corresponding oath of protection and granted a fief, usually tenure of land, to his baron vassal.5 In succession, this baron became a lord, granting pieces of his own fief to vassal knights for the same oath of fealty. This process by which a vassal could become a lord and grant parts of his own fief to other vassals was called subinfeudation. By this procedure, a knight could rent pieces of his own fief to peasants. After swearing oaths of fealty to provide food and military services to their lord, these peasants became serfs or villeins. Feudal land and holdings were generally hereditary, passing on to sons or male cousins. Unlike English feudalism, Japanese landholders did not have to swear oaths of fealty to receive fiefs. Instead, the shogun appointed stewards called jito to oversee the official owners. Similar to the English baron, a lower territorial class called daimyo became the land holding aristocracy. But because the shoguns did not exact an oath of fealty from the daimyo, the aggressive daimyo became the greatest military threat to the shogunate in later years. Resembling English knights, samurai were the military backbone of the Japanese feudal system. Japanese peasants, like their European counterparts, served as farmers at the bottom of the feudal pecking order.4 Both Japanese and English feudal systems were dominated by military strength controlled by the respective hierarchies. English knights, and their Japanese equivalents, samurai filled this feudal need for military forces. Samurai derived their name from a Japanese verb meaning "to serve," which accurately described their social station as military servants. Although differing culturally, samurai and knights were comparable in several ways. First, knights and samurai both lived by codes of honor. Knights were bound by a code of chivalry, and Japanese samurai by Bushido (the way of the warrior). Still, these codes of honor differed in their respective focuses. According to the selfless emphasis of their Christian background, English knights took a chivalrous oath to "protect the weak, defenseless, and helpless, and fight for the general welfare of all."6 Although hinging on family honor, the samurai warrior code of conduct stressed "personal bravery and prowess, honor and loyalty. a hard, Spartan life and avoidance of luxuries, and expected a samurai to face pain and death with indifference."7 Samurai were greatly influenced by Confucian ideals which emphasized personal honor and individual loyalty to one's master. Unlike chivalrous knighthood which addressed only males, the Bushido warrior code included female samurai. Another difference between the feudal relationships was that an English knight was directly rewarded with a fief of land by his lord. In contrast, the Japanese samurai was rewarded for faithful service by a fee of income from his lord's lands. Also differentially, knights wore heavy chain link armor, but samurai were protected by light, flexible armor. Both samurai and knights used spears and swords and fought on horseback.8 hough differing in monetary rewards, armor, and application of their codes of honor, samurai and knights resembled each other as the military resources of their separate feudal systems. Derived from the Latin word servus, meaning servant or slave, the word serf accurately described the status of English peasants.9 t first, English peasants were expected to pay exorbitant taxes in cash to the lord in return for the land they rented. Instead of being sold into slavery when he could no longer pay the required taxes, the peasant's land, possessions, and labor became the property of the lord. Legally bound to his feudal lord's land as serfs, a peasant was expected to provide physical labor, pay a percentage of produce, and work on the demesne, the lord's own portion of land. In return, the lord protected his serfs from martial molestation in his manor, or castle.9 Unlike English serfs in proto-slavery, the occupation of Japanese peasants is better described as shiki: "a separate right or profit derivable from it that is vested in a person."10 Japanese peasants occupied a separate cultivator class; some actually owned land while others tilled the ground. Like English feudalism, Japanese peasants worked their rice fields, giving a portion of their produce as rent to their landlords. In contrast to English peasants, Japanese serfs willingly gave up their rights and land to their daimyo landlords, in order to avoid the high property taxes of Japan.4 Interestingly, Japanese peasants enjoyed greater freedom than English peasants, since some could actually own land. Still, thanks to the rise of the elite samurai, serfs in Japan were locked into a farming class order for several centuries. Ultimately, both Japanese and English peasants were the backbone of the feudal system because of the pressing need for farm workers and incessant agricultural production. One defining difference between these two feudal systems was their respective religions, Christianity in England, and Shinto and Buddhism in Japan. Since the feudal systems were both based on a need for military services, the respective authorities used religion to inspire their armed forces. Thus, both the medieval knights and samurai fought for their beliefs. Motivated by pressure from the Catholic Church, knights fought for the crown and for Christ during medieval efforts to retake Jerusalem through the Crusades. Differentially, samurai warriors fought for the Shinto inspired honor of Bushido, for the family and the Emperor. In other words, knights fought for God's glory and samurai fought for their own glory. On the battlefield, the religions of Christianity and Buddhism influenced knights and samurai in divergent ways. The Sixth Commandment from Exodus 20:13, "Do not murder," and the Biblical principal of Genesis 9:5, "For your own lifeblood I will surely require a reckoning. . ." clearly instructed Christian knights not to kill themselves, even if humiliated by defeat. But Buddhism teaches the reincarnation of life leading to ultimate nirvana which is a blissful release from suffering. So if disgraced by defeat in battle, samurai would "escape" by committing hara-kiri, the ritual suicide. The final difference between samurai and knights consisted in who reaped the glory for valiant conduct in battle. While knights gave honor to God for their victories as part of a long history of JudeoChristian tradition, samurai gave glory to their dead ancestors holding to the promise of Buddhism. Throughout the years, the feudalistic systems of both Japan and England were revised and finally abolished. In Japan's case, feudalism ended as the emperor Meiji overthrew the shogunate and regained his imperial power in the Meiji Restoration of 1868. While the government became centralized, immense reforms occurred as social barriers were overturned and the daimyo were forced to return their feudal fiefdoms to the emperor.11 But in England, no uprising ended feudalism abruptly. Instead in 1215, King John signed the Magna Carta which revised the power of feudal lords, and reevaluated the rights of vassals. Also, the Crusades contributed indirectly to the downfall of English feudalism. With the introduction of money circulation after the Crusades, authorities could pay their subordinates in cash, rather than grants of fief land. England was on an unstoppable road to eliminating feudalism. By the end of the Middle Ages, England had switched from human labor, and proceeded almost directly into the machine labor of the Industrial Revolution.12 Ultimately, these separate feudalism systems were similar in overall organization. Both feudal societies were based on the tenure of land in exchange for military service. Both systems were used by Japanese and English rulers to consolidate and control their realms. And in both systems of feudalism, land held the primary focus in determining social order; the aristocracy owned the land, soldiers protected the land and its owners, while farming peasants tilled the land. But neither society was based on the second commandment of Jesus from Matthew 12:31, "The second is this: 'Love your neighbor as yourself.' There is no commandment greater than these." Instead, the rich and powerful of both systems exploited the peasants, reducing them to near slavery for monetary gain. Major differences between the two systems occurred in the details of application, such as the allegiance of a vassal to his lord. English vassals owed loyalty to their lord and to the king, thereby stabilizing the system. But since daimyo did not swear faithfulness to the shogun, their fighting among each other and against the shogunate plunged Japan in civil war for almost four hundred years. This lack of allegiance perfectly illustrated Matthew 12:25, "Every kingdom divided against itself will be ruined, and every city or household divided against itself will not stand." Another difference consisted of the method of repayment for knights and samurai. While knights received a fief of land from their overlords for their military services, samurai collected a salary, not tenure of land. Also, Japanese peasants differed from English serfs in the amount of freedom they enjoyed. In conclusion, even though the systems resembled each other superficially, Japanese and English systems of feudalism proved divergent in actual application of feudal relationship. Commentary: Both feudal systems did not honor the second most important commandment, “Love your neighbor as yourself” (Matthew 12:31). For they did not treat the peasants well by taking advantage of them. It may be that the Japanese were a little better because the Japanese peasants were given freedom to own land, but keeping them low on the social ladder was cruel. The knights, with their code of chivalry, may have been more Christian-like than the samurai, but many of them may not have truly followed the code. The samurai, on the other hand, did not live for a Biblical purpose but that is mainly because the only religions they knew of were Buddhism and Shintoism. Because of that, they did not know that it is appointed unto man once to die, and afterthat, the judgement. They thought that life continued on earth in another form and therefore they thought the suicide of hara-kiri would preserving their honor rather than facing this particular life with disgrace. The militaristic pride and heathen traditions of the samurai led to death. In contrast, the Christian traditions of knights and Biblically based chivalry lead to life.