Waste incineration controversy in China: Contesting Technologies

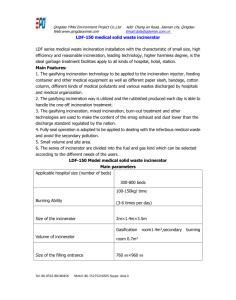

advertisement

Waste Incineration Controversy in China: Contesting Technologies and Debating Expertise ZHANG Jieying The Chinese University of Hong Kong In last 30 years, China has experienced a booming economic growth and rapid urbanization. Used to “struggle hard” in socialist era, people now are enthusiastically embracing the consumptionism; celebrating their new identities as customers. A consequence of this is a waste crisis– almost all the cities are besieged by landfills and municipal governments are facing an unprecedented challenge to treat huge amounts of waste. To deal with this, local governments start the constructions of treatment projects such as waste incineration power plant. However, these plans are facing fierce not-in-my-back-yard protests by surrounding residents, due to the rising rights consciousness of Chinese people as well as their emerging environmental concerns. The protesters maintain that toxic emissions from waste incinerating, dioxin in particular, probably cause cancer. This research is a scrutiny of the anti-incineration campaign in post-socialist China. Employing an anthropological methodology, I did my 12-month field work in Guangzhou, worked closely with a local anti-incinerator NGO and a waste treatment research institution. Focusing on the controversy of waste incineration technologies, I examine how the pro-incineration governments and experts legitimize waste incineration and how the anti-incineration activists challenge the authorities accordingly. Applying global green discourses, supporters argue that incineration power plant, as “new energy and green technology”, fits in with the state agenda of “sustainable development”. Through popular science education and propaganda, they represent incinerator as a modern, advanced and flawless high-tech facility to the public. On the other hand, anti-incineration activists construct their own expertise through self-teaching and investigation. They challenge the authorities by questioning the emission data and pointing out the operational risk of the incinerator. Further, they analyze the composition and property of the waste generated by Guangzhou residents and argue that incineration is not the most “locally appropriate” technology to treat waste. I read the campaign as a dynamic process of knowledge production. Institutions such as local governments, research institutions, NGOs and individuals like technocrats, researchers, activists and citizens actively participate in this process and constitute a rhizomatic network within which three clusters of knowledge are being exchanged, transferred and reconstructed: 1, the technical knowledge of waste incineration and physicochemical properties of emissions are represented, circulated and conceived; 2, the ideas of “what is waste” and “what is a locally appropriate way to treat waste” are invoked, redefined and integrated; 3, the global environmental protection discourses, ecological thoughts and ethics are introduced, translated and employed. I argue that the anti-incineration campaign in China is not simply a story of “scientific elitism vs. the ordinary people”. In this story, the anti-incineration activists actively construct themselves as grass-roots experts via synthesizing multiple types of knowledge, including science. What I am trying to present is how two kinds of “expertise” compete with each other in this process. Moreover, the incineration technology controversy is not necessarily the encounters between the global technoscience and local knowledge. Rather, the technologies under dispute as well as what constitutes the “local” are being articulated and reconstructed constantly in the debate.