View/Open - Lirias

advertisement

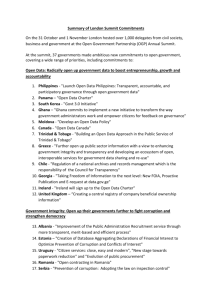

1 Transparency and freedom of information: a complex relation Paper for the Transatlantic Conference on Transparency Research 2012 Utrecht, The Netherlands 8 and 9 June 2012 Work in progress: please do not quote! Prof. dr. Frankie Schram Visiting professor Faculty of Social and Political Science and Faculty of Law of the University of Antwerp Visiting professor Public Management Institute, Faculty of Social Sciences of the KU Leuven Secretary and member of the Commission for Access to and reuse of administrative documents Secretary and member of the Federal Appeal Commission for Access to Environmental Information Member of the Flemish Supervision Commission for the exchange of electronic administrative data traffic 2 CONTENTS 1. Transparency 1.1 What is transparency about? 1.2 The functioning of the concept of transparency 1.3 In search of a definition for transparency 1.3.1 The general content of transparency 1.3.2 Transparency in public law and administrative science 1.4 The functioning of ‘transparency’ in a legal context 2. Freedom of information and freedom of information laws 2.1 Freedom of information 2.2 Freedom of information and freedom of information legislation 2.2.1 Freedom of information legislation organises freedom of information 2.2.2 Freedom of information legislation organises more than freedom of information 3. FOI-Legislation and transparency 3.1 FOI-legislation can lead to more transparency but not necessary… 3.2 FOI-legislation contains a legal obligation, transparency is only a principle 3.3 Most of the FOI-legislation creates a legal state, transparency is only a fact 3.4 FOI-legislation considers in the first place an obligation on public administrations to the public, that is not necessarily the case for transparency or the principle of transparency 3.5 Transparency has a broader scope than a right of public access 4. To a more effective content for the concept of transparency 4.1 Transparency as a factual state 4.2 Transparency as a principle of governance 4.3 Transparency as a general legal principle 4.4 Transparency as an ethical value and as an aspect of integrity 4.5 Transparency is no goal in itself 5. Conclusion 3 1. Transparency 1.1.What is transparency about? Transparency has become a popular word, used in very different contexts. Not only it is used to talk about the relations between citizens and government, between citizens and administrations, between citizens and legislators, is also used in other contexts, including monetary policy, economic policy, enterprises and associations. 1 The concept of transparency operates in all domains of social life "qu’il s’agisse de comptes des sociétés commerciales, des informations économiques dues aux salariés et aux actionnaires, de la protection des consommateurs, de la passation des marchés... les nouveaux droits ouverts aux citoyens supposent la transparence à l’information, c’est-à-dire la possibilité de connaître directement, sans filtre déformant, la réalité des faits". It significance and role it plays, also differs from the scientific discipline where it is used (law, administrative science, management, political science, philosophy). Transparency has a long history as a central principle for public management, and for democratic and corporate accountability more generally.2 Often its stated that the concepts of transparency was introduced in the early 1980s but that the explicit term transparency was not used until about ten years later. According to some other scholars the concept was even introduced in the middle of the ’70.3 One of them, LAFAY4 is of the opinion that the concept is even older and was introduced in de years 60-70 to rethink the traditional administrative model: against the enclose and secrecy that were seen as negative was placed the figure of transparency seen as pure positivity. Transparency became the keyword to express the dynamics of an evolution that touched the administration.5 But, according to HOOD the term itself became only a general catchword at the end of the twentieth century.6 It is not so clear what is meant with transparency exactly. Nevertheless, transparency is first of all a receipt against the growing complexity of society, against the growing globalisation and an element of the process of democratization. People want to control their environment: the more complex a society is, the more the need for more transparency is, because its helps people to manage their live. But there is not only the individual need, there are also the theoretical frameworks of good governance and that of the network society, which explains the need for transparency. The good governance concept is an answer of the administrative sciences to explain the way policy is made from the experience that the public sector is not the only player in the development and implementation of policy. Not only the public sector plays a role, but it is 1 Ch. DEBBASCH, La transparence administrative en Europe, Centre national de la recherche scientifique Paris, 1990, 331 p.; J. RIDEAU (ed.), La transparence dans l'Union européenne: mythe ou principe juridique?, LGDJ, Paris, 1999, 276 p. 2 C. HOOD, “What happens when transparency meets blame-avoidance”, Public Management Review 2007, 9:2, 192. 3 P.F. DIVIER, “L’administration transparente: l’accès des citoyens américains aux documents officiels”, Revue de droit public, 1975, 59; P. DIBOUT, “Pour un droit à la communication des documents administratifs”, Revue administrative, nr. 173, 1976, 503: he talks about the necessity “d’organiser la transparence”. 4 F. LAFAY, “L’accès aux documents du Conseil de l’Union , 37. 5 J. CHEVALLIER, “Une notion très complexe”, in X., La transparence administrative, (Problèmes politiques et sociaux, nr. 679), 1992, 4. 6 C. HOOD, “A Historical Perspective on Transparency”, in C. HOOD and D. A. HEALD (eds.), Transparency: The Key to Better Governance?, Oxford, British Academy/Oxford University Press, 2006. 4 recognised that also different stakeholders plays an important role in the preparation and in the implementation of policy. In a lot of cases the success of policy is not in the hands of government alone or the role of government is rather very limited.7 The realisation of a certain policy is in governance theory seen as more complex than before and this causes uncertainty. The same can be said of the network society. In a network society there is less room for hierarchy. Actors interact on a more equal base.8 Transparency is a complex construct with a long history that implies increased government openness to public scrutiny, increased citizens’ access to government information and engagement in the decision-making process, and making agencies more transparent to their employees through facilitating access to information, knowledge sharing and collaboration. 9 1.2.The functioning of the concept of transparency Like so many good-governance catchwords in public management and administrative science, transparency is more often invoked than defined. According to HOOD transparency is one of those ‘banal’ ideas10 that are taken as unexceptionable in discussions of governance and public management.11 At the most general level the word can be said to denote “government according to fixed and published rules, on the basis of information and procedures that are accessible to the public, and (in some usages) within clearly demarcated fields of activity”.12 Everyone is in favour of 'transparency', but nobody knows exactly what is meant by it. According to J. CHEVALLIER although nobody exactly knows what it means, it isn’t a meaningless word: C. ANSELL en A. GASH, “Collaborative governance in theory and practice”, Journal of Public Administration and Theory 2008, 19, 543 – 571; 8 RHODES, Governance and Public Administration, in: J. Pierre Debating Governace: Authority, Steering and Democracy, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000, JESSOP, “Governance, governance failure, metagovernance”, in Participatory governance in multilevel context: concepts and experience, Opladen, Leske and Budrich, 2002, 33 – 58; E.-H. KLIJN en J. KOPPENJAN, “Public management and networks. Foundations of a network approach to governance”, Public Management 2000, 2, 135 – 158; E.-H. KLIJN, J. KOPPENJAN, K. TERMEER, “Managing networks in the public sector: a theoretical study of management strategies in policy networks”, Public administration 1995, 73, 437 – 454; E..-H. KLIJN en C. SKELCHER, “Democracy and governance networks: compatible or not?”, Public administration 2007, 85, 587 – 608; E.-H. KLIJN en J. EDELENBOS, “The impact of network management on outcomes in governance networks”, Public administration 2010, 88, 1063 – 1082; J. KOPPENJAN en E.-H. KLIJN, “Besluitvorming en management in netwerken: een multi-actor perspectief op sturing”, in T. ABMA en R.J. IN ‘T VELD (eds.), Handboek beleidswetenschap, Amsterdam, Boom, 2001, 179 – 192; M. MANDELL en R. KEAST, “Evaluating network arrangements: towards revised performance measures”, Public performance and management review 2007, 30, 474 – 597. 9 I.V. POPOVA-NOWAK, “What is Transparency?”, in W.M. BURKE en M. TELLER, A Guide to Owning Transparency. How Federal Agencies can Implement and Benefit from Transparency, Washington, Open Forum Foundation, 2011, 14. 10 Used in the sense of pervasive but unexamined, as in Michael Billig’s notion of banal nationalism, M. BILLIG, Banal Nationalism, London, Sage Publications, 1995, 208 p. 11 C. HOOD, “What happens when transparency meets blame-avoidance”, Public Management Review 2007, 9:2, 192. 12 C. HOOD, “Transparency” in P.B. CLARKE and J. FOWERAKER (eds.), Encyclopaedia of Democratic Thought, London, Routledge, 2001, 701. 7 5 “Caractérisé par une remarquable polysémie, dans la mesure où il recouvre un ensemble de significations complexes, subtilement imbriquées les unes dans les autres et articulées en chaîne significante, le mot fait l’objet de commutations positives et suscite des résonances profondes”.13 He stresses that, although the notion refers to a variety of ideas, behind it there are essential expectations. The notion is not neutral: it has “la valeur d’un mythe porteur de transformations”, because it responds to deep aspirations of people, groups and individuals.14 It has also become a commonplace to see it as intrinsically virtuous, in so far as more transparency is taken as necessarily implying a better quality of democratic control. 15 It fulfils a regulating function in the daily life of a modern democracy.16 Transparency is a magic word that arises regularly in the national and the European context. It a vague collective term that has a different content dependant of the domain within the term is used.17 Everyone had to be in favour of ‘transparency’. It’s difficult to say you are in some situations against it. That transparency is seen as purely positive can nevertheless be dangerous, because expectations can become too high. Transparency is not always the best solution in every circumstance. In his doctoral dissertation AUDRIA confirms the multi-signifiance of the concept: “la notion de transparence est utilisée partout mais avec des significations bien différentes suivant les opérateurs qui utilisent cette notion et pour des buts plutôt disparates.”18 But important is that he stresses another element in the use of the concept: it serves also to justify reforms in and formulate demands to administration : “On doit bien faire le constat que le concept de la transparence ne reste pas univoque et qu'il sert finalement de concept « fourre-tout », que ce soit pour justifier une réforme, ou pour justifier une revendication quelconque.”19 Also within the discourse on the European Union, transparency plays a specific meaning: it is placed against the so-called lack of democracy of the European Union that is considered to be a reality and the complexity of the European construct.20 Despite the very unclear character of the notion, one cannot deny that transparency has a real place in the language of the European Union.21 The role that transparency plays within the EU is outlined by F. LAFAY as follows: J. CHEVALLIER, “Une notion très complexe”, in La transparence administrative, (Problèmes politique et sociaux), nr. 679, 1992, 4. 14 J. RIDEAU, “Jeux d’ombres et de lumières en Europe”, in J. RIDEAU (ed.), La transparence dans l'Union européenne: mythe ou principe juridique?, LGDJ, Paris, 1999, 1. 15 H. WALLACE, “Transparency and the legislative process in the European Union”, in J. RIDEAU, (ed.), La transparence dans l'Union européenne: mythe ou principe juridique?, LGDJ, Paris, 1999, 113. 16 C. LEQUESNE, “La transparence vice ou vertus des democraties?”, in J. RIDEAU (ed.), La transparence dans l'Union européenne: mythe ou principe juridique?, LGDJ, Paris, 1999, 13. 17 R.J.G.M. WIDDERSHOVEN, M.J.M. VERHOEVEN, S. PRECHAL, A.P.W. DUIJKERSLOOT, J.W. VAN DE GRONDEN? B. HESSEL, R. ORTLEP, Derde evaluatie van de Algemene Wet Bestuusrecht 2006. De Europese Agenda van de Awb, Den Haag, Boom Juridische uitgevers, 2007, 85. 18 R. AUDRIA, New public management et transparence : essai de déconstruction d’un mythe actuel, Geneva, University of Genève, 2004, 9. 19 R. AUDRIA, o.c., 9. 20 P. BIRKINSHAW, "Freedom of Information and Openness: fundamental human rights?”, Administrative Law Review 2006, 189. 13 6 “La transparence n’est plus seulement une condition d’efficacité de l’action communautaire, à laquelle contribue l’individu lui-même en tant que bénéficiaire d’une obligation de transparence, mais elle est aussi une condition de légitimité de l’action communautaire et concerne cette fois, le citoyen, observateur critique de cette action”.22 1.3.In search of the definition of transparency 1.3.1. The general content of transparency In scientific literature there are various attempts to define or describe the notion. General definitions of transparency define it as ‘lifting the veil of secrecy’ 23 or ‘the ability to look clearly through the windows of an institution’24 or “making the invisible visible”25. According to A. MEIJER the general idea is that something is happening behind curtains and once these curtains are removed, everything is out in the open and can be scrutinized.26 Patrick BIRKINSHAW expresses that idea as follow: “Transparency is the conduct of public affairs in the open or otherwise subject to public scrutiny’.27 This definition can be completed by a negative dimension: “[Transparency] is contrasted with opaque policy measures, where it is hard to discover who takes the decisions, what they are, and who gains and who loses.”28 Transparency is not easy: it has to be created and directed. 1.3.2. Transparency in public law and administrative science In the context of public law and administrative science two types of definitions exists: one the one hand there are descriptive definitions, on the other hand there are normative definitions. More large definitions can be distinguished from more narrow definitions. According to Y. JEGOUZO “engloberait (le droit à la transparence administrative) ... l’essentiel des procédés qui ont visé à améliorer les relations entre l’administration et les administrés, c’est à dire non seulement ceux qui tendent à lever le secret administratif mais aussi ceux qui tendent à faire peser sur l’administration l’obligation d’accompagner son action de mesures de publicité ou d’information active, ou d’y associer les administratrés, notamment par la consultation".29 Within this context, his definition of what he calls “droit à la transparence administrative" is “l’ensemble des procédés juridiques visant à permettre aux K. St. C. BRADLEY, “La Transparence de l’Union Européenne: une évidence ou une trompe l’œil?”, Cahiers de droit européen, 1999, 286. 22 F. LAFAY, “L’accès aux documents du Conseil de l’Union: contribution à une problématique de la transparence en droit communautaire”, R.T.D.E. 1997, 38 – 39. 23 J. DAVIS, “Access to and Transmission of Information: Position of the Media”, in V. DECKMYN and I. THOMSON (ed.), Openness and Transparency in the European Union, Maastricht: European Institute of Public Administration, 1998, 121. 24 M. DEN BOER, ‘Steamy Windows: Transparency and Openness in Justice and Home Affairs”, in V. DECKMYN and I. THOMSON (ed.), Openness and Transparency in the European Union, Maastricht: European Institute of Public Administration, 1998, 105. 25 M. STRATHERN, “The Tyranny of Transparency”, British Educational Research Journal 2000, (26) 3, 390. 26 A. MEIER, “Understanding modern transparency”, International Review of Administrative Sciences 2009, 75 (2), 258. 27 P.J. BIRKINSHAW, “Freedom of Information and Openness: Fundamental Human Rights”, Administrative Law Review 2006, 58(1), 189. 28 J. BLACK, “Transparent Policy Measures”, Oxford Dictionary of Economics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997, 456. 29 Y. JEGOUZO, Le droit à la transparence administrative, Etudes et Documents, 1991, 199 en 200. 21 7 administrés de pénétrer dans le système administratif et ainsi de faire échec au droit (et le plus souvent à l’obligation) de l’administration au secret". « La transparence administrative » is here clearly linked to the relation between the administration and citizens. That’s not always the case. According to C. BENEDEK en Ph. DE BRUYCKER30, followed by M. KLIJNSTRA31 en J. TOUSCOZ32, the concept has no clear circumscribed legal content. BENEDEK en DE BRUYCKER distinguish a concept with a large content form a concept with a more limited content.33 The large concept includes a big number, very different concepts as the rights of defence, public, reports of activities of public entities, the means of parliament to control the executive, communication of public authorities, the existence of an ombudsman, de modalities of the administrative procedures in general and the participation of the citizens to administrative activities, formal obligation to motivate, … KLIJNSTRA adds to this list “voorlichting”, of meetings, participation, access to a judge and public access to information, elements that also frequently has a place in literature and European legislative history. In this sense “transparency” is a collection of some fundamental safeguards in public law.34 It is clear that transparency doesn’t mean that one can have a right of participation. But some authors put it otherwise. Kieran ST. C. BRADLEY has remarked that the Member States and the Institutions in their position-taking in the preparation of the Treaty of Amsterdam treated a large group of themes under this notion: the openness of the functioning of the Institutions, the simplification of the treaties, the simplification of the legislative procedures, the amelioration of the quality of the drafting and the presentation of the legislation of the Union, the openness of the procedure to modify the treaties, the reinforcement of the role of the national parliaments in the decision making process, the amelioration of the consultation of the interested public in the preparation phase of the processes, elimination of jargon in the declarations of the Institutions.35 Although public access to information and the free access to administrative documents leads logically to participation, participation is clearly distinct from it and don’t lead necessarily to it. Participation means that a pubic authority give to citizens the possibility to express their wishes on a decision that has to be taken. As H. KONING states, participation presumes at least that the administrative authority provokes participation and makes possible by giving sufficient information in time and that the administrative body take knowledge of the expressed wishes en gives them a role in the balancing of interests in the decision making process.36 Almost an even large definition is given by F. LAFAY. Under the concept “transparence” falls according to hem beneath the classic measures of control of Parliament also the access to C. BENEDEK en Ph. DE BRUYCKER, "La transparence de l’administration. Quelques observations à propos de l’accès aux documents administratifs en droit belge", in Présence du droit public et des droits de l’homme. Mélanges offerts à Jacques Velu, dl. 2, Brussels, Bruylant, 1992, 783. 31 M. KLIJNSTRA, "Het transparantiebeginsel toegespitst op de openbaarheid in het milieurecht", Milieu en Recht 2000, 3. 32 J. TOUSCOZ, "Réflexions sur la transparence en droit international économique", in J. RIDEAU (ed.), La transparence dans l’Union européenne. Mythe ou principe, Paris, L.G.D.J., 1999, 225: "La notion de transparence relève, a priori, du vocabulaire pictural, architectural, poétique plutôt que du vocabulaire juridique." 33 C. BENEDEK en Ph. DE BRUYCKER, o.c., 783. 34 M. KLIJNSTRA, o.c., 3. 35 K. St. C. BRADLEY, o.c., 286. 36 H. KONING, "Inspraak volgens nieuwe wetten", Nederlands Juristenblad 1990, 1064. 30 8 administrative decisions, de respect for the rights of the defence, public hearings, obligation to motivate certain actions, the right of each person to have access to administrative documents, the possibility to give objection against certain decisions, the installation of an ombudsman who deals with complaints and a real place for the users of public services. 37 In a more limit sense, transparency refers to public access to administrative documents. In administrative law a difference is made between an administrative action and an administrative procedure. Administrative transparency can deal with both aspects. Applied to the administrative procedure, it refers to de participation of the citizens in the internal decision making procedures of the administration. This participation can present itself in different forms. Applied to the administrative action, it refers to the access that is given to a formal decision. This aspect is more often ruled in laws and other regulations that this is the case for procedures because it is essential that citizens can know their rights and obligations. It is a condition to invoke a decision against the citizens: a decision that is not properly made public, has no obliging power for the citizens.38 KLIJNSTRA prefers a more limit definition of the concept of “transparency”. Next to the right of every citizen to have access to information, it includes also the obligation of the administration to give active information to make its policy and activities more comprehensible. According to this scholar also access to meetings and public communication fall within this notion. Further the concept includes also that decision making procedures and the safeguarding of legal rights has to be transparent. Transparency is also found in the discours of obscurity and the strong disintegration of legislation.39 J. TOUSCOZ derives from the factual use that legal experts make of the word ‘transparency’ it significance: the essence of it is a technique to be informed: La transparence pour le juriste est une procédure, une technique qui permet de voir, de connaître, d’être informé. Elle est en rapport avec la publication, le contrôle, la communication, l’information, la transmission, voire même la publicité. Elle se présente différemment selon qu’il s’agit de rendre transparente une règle de portée générale ou une décision individuelle. Il faut aussi distinguer, a priori, les cas où la transparence doit s’établir entre des sujets de droit liés entre eux par un contrat ou une procédure contentieuse par exemple (la transparence concerne alors la bonne foi, la diligence, le principe du contradictoire) et les cas où la transparence doit bénéficier à un large public voire à un public indifférencié (elle relève alors des techniques de publication).40 G. BRAIBANT hasn’t formulated a definition of « transparence administrative », but he has given the concept content by summing up the seven pillars of it and by clarifying these pillars. These pillars are: respect for the rights of defence, possibilities of participation, the disclosure of projects, the disclosure of decisions, the public access to debates, the access to administrative documents and the motivation of administrative acts.41 37 F. LAFAY, o.c., 37 - 38. C. BENEDEK en Ph. DE BRUYCKER, o.c., 784 - 785. 39 M. KLIJNSTRA, “Het transparantiebeginsel toegespitst op de openbaarheid in het milieurecht”, Milieu en Recht, 2000, 4. 40 J. TOUSCOZ, o.c., 225. 41 G. BRAIBANT, Reflexions sur la transparence administrative, A.P.T., jg. 17, 1993, 58 - 59 38 9 Also M. VERDUSSEN en A. NOËL in following G. BRAIBANT and C. BENEDEK accentuate that de notion of “administrative transparency” is a complex notion that has different aspects. The word has also a varying content. De essence of the concept is according to them to being found in the right of information that inscribes itself in an active extension of the right of freedom of expression and of freedom of press.42 According to Ch. DEBBASCH the concept is larger than the concept of freedom of information. To the concept belong three aspects: the right to know, the right to control and the right to be seen as a user and no longer as a subject of law. On the other side, he distinguishes three dimensions, namely the right of access to administrative documents, de right of access to administrative decisions and participation.43 In a more narrow sense, ERGEC uses the concept of “transparence administrative”. According to him this right is derived of the right of the citizen to information that itself includes the right to receive information and to discover it. Two elements of this right are present in law: the right of access of the citizens to administrative documents and the formal obligation to motivate administrative decisions.44 In the same way, C. DE TERWANGNE and Th. DE LA CROIX-DAVID are speaking about “la transparence de l’administration”, but these scholars doesn’t exclude that the concept includes also other aspects.45 In the same line, the vision of Jacob SÖDERMAN, the former European Ombudsman can be placed. In his report 'The citizen, the administration and Community Law' he distinguishes three elements of transparency: - the processes through which public authorities make decisions should be understandable and open; the decisions themselves should be reasoned; as far as possible, the information on which the decisions are based should be available to the public.46 In this definition the accent lies on the legal dimension: the formal motivation for decisions and free access to public information. There is also a dimension that concerns the ways decisions are made. What is missing in his definition is that transparency also has to do with a mentality of openness. Although Bo VESTERDORF does not give transparency the same meaning as Mr. SÖDERMAN, he also places its content in the legal sphere: in his view it covers at least the four following important principles: (1) the right to a statement of reasons for a decision, 42 M. VERDUSSEN en A. NOËL, "Les droits fondamentaux et la reforme constitutionnelle de 1993", A.P.T. 1994, 132. 43 Ch. DEBBASCH, o.c., 12 - 13. 44 R. ERGEC, Introduction au droit public. Tome II, Brusselss, Story-Scientia, 1990, 57. 45 C. DE TERWANGNE en Th. DE LA CROIX-DAVIO (ed.), L’accès à l’information administrative et la commercialisation des données publiques, Facultés Universitaires Notre-Dame de la Paix de Namur. Cahiers du Centre de Recherches Informatiques et Droit, Story Scientia, Diegem, Kluwer Editions Juridiques Belgique, 1994, 3. 46 J. SÖDERMAN, The Citizen, the Administration and Community Law, General report for the 1998 Fide Congress. Stockholm, Sweden, June 3 – 6, 1998, 6; See also: J. SÖDERMAN, Transparency as a Fundamental Principle of the European Union, speech for the Walter Hallstein Institute, Humboldt University, Berlin, 19 June 2001. 10 (2) the right to be heard before a decision is taken, (3) a party’s right of access to the file, (4) the public’s right of access to information.47 What is missing here is that transparency not only includes understandable procedures, but also understandable structures connected with them. Very interesting are the considerations of auditor-general TESAURO given in the case C-58/94. According to him transparency has to do with adequate access, so that citizens in the decision making faze are informed of the actions and measures that are made. Only than can really and efficient, also on level of public opinion, control be exercised and real participation come into being. 48 In the scientific literature the concept of transparency has different meanings: there are more large definitions and more narrow definitions. There is also the context where the concept is used that is very different: a legal context, a national context, a context of the European Union. Also one has take into consideration that the place transparency has, is different according to the language where it is used and the presence of other similar concepts it a certain language. 1.4.The functioning of ‘transparency’ in a legal context Is the definition of transparency is unclear, that is also the case for the way transparency is functioning in a legal context. Is it a legal concept and if so what is its nature, or is it only a principle of good governance, a principle that offers guidance for legal action?49 In some specific legislation transparency functions as a legal principle. This is particular the case in European Union law. That is for example the case for procurement procedures. Also in other domains of European law, the Court of Justice has developed a principle of transparency and although there is a tendency that the principle of transparency is developing to a norm for the actions of public authorities and for a norm of control of these actions, it is not yet a general principle of law.50 The principle of transparency is at this moment to much linked to specific economic matters and the functioning of a free internal market. The European Union has become more than a purely economic union. Where transparency and the principle of transparency function as a working principle for the Union’s decision making process, it has little legal consequences. A general principle of law is growing.51 That can be seen in a recent B. VESTERDORF, “Transparency – not just a vague word”, Fordham International Law Journal, 1999, 903. Case C-58/94, Jur., 1996, I-2169. 49 See i.e. Explanatory Report of the Tromsø Convention: “Transparency of public authorities is a key feature of good governance and an indicator of whether or not a society is genuinely democratic and pluralist, opposed to all forms of corruption, capable of criticising those who govern it, and open to enlightened participation of citizens in matters of public interest.” 50 See f.e. R.J.G.M. WIDDERSHOVEN, M.J.M. VERHOEVEN, S. PRECHAL, A.P.W. DUIJKERSLOOT, J.W. VAN DE GRONDEN? B. HESSEL, R. ORTLEP, Derde evaluatie van de Algemene Wet Bestuusrecht 2006. De Europese Agenda van de Awb, Den Haag, Boom Juridische uitgevers, 2007, 86, 89; J.M. COMMUNIER, “Le principe de transparence: Réflexions sur la qualification et sa portée”, in: Le droit de l’Union européenne en principes. Liber amicorum en l’honneur de Jean Raux, Rennes, Editions Apogée, 2006 ; M. O’NEILL, « The rights of access to community-held documentation as a general principle of EC law », European Public Law 1998; 4:3, 403-432. 51 Some scholars defend the position that the transparency principle is already to be considered as a general principle of law: see A.W.G.J. BUIJZE, “Waarom het transparantiebeginsel maar niet transparent wil worden”, NtEr September 2011/ nr. 7, 240 – 248; A.W.G.J. BUIJZE en R.J.G.M. WIDDERSHOVEN, “De Awb en Eu47 48 11 judgement of the Court of Justice: “That being the case, the contested decision challenges the fundamental principle of transparency. (60) (…) The contested decision does not contain any adequate reasoning capable of justifying the making of an exception to the principle of transparency in the present case. (61) (…) In that connection, the fact that the use by the Members of Parliament of the financial resources made available to them is a sensitive matter followed with great interest by the media, which the applicant does not deny – quite the contrary – cannot constitute in itself an objective reason sufficient to justify the concern that the decision-making process would be seriously undermined, without calling into question the very principle of transparency intended by the EC Treaty (80).”52 In national law the principle of transparency is often not explicit present. Some elements of it are sometimes derived from other general principles of law or from general principles of administrative law Transparency is unmistakable linked to basic concepts as “democracy” and “Rechtsstaat”.53 The Court of Justice expresses the link with democracy as follows: “In those circumstances, openness makes it possible for citizens to participate more closely in the decision-making process and for the administration to enjoy greater legitimacy and to be more effective and more accountable to the citizen in a democratic system. (…) If citizens are to be able to exercise their democratic rights, they must be in a position to follow in detail the decisionmaking process within the institutions taking part in the legislative procedures and to have access to all relevant information.”54 Although the “Rechtsstaat” principle is also a theoretical framework for defending transparency, it has in itself also a limitation. Most countries that have taken the form of a “Rechtsstaat”, contains rules how the relations between the different powers in the state are divided.55 The form of democracy concretised in the Rechtsstaat is in most cases a representative democracy, with some corrections. It has as result that the level of transparency isn’t the same, and more is in principle not the same. In my view transparency is in the first place a concept of good governance.56 This is shared by B. FRYDMAN. According to him: “La transparence n.est pas un mythe, mais cela n’en fait pas pour autant un concept juridique. Elle exprime une valeur, mais surtout elle dénote un fait.”57 It is not yet a general principle of law, although in some cases it is expressed in legislation and derived by jurisprudence. But than the word ‘transparency’ is not used in legislation, in some cases the word ‘openness’ is used.58 Although some scholars make no difference between recht: het transparantiebeginsel”, in T. BARKHUYSEN, W. DEN OUDEN en J.E.M. POLAK (ed.), Bestuursrecht harmoniseren: 15 jaar Awb, Den Haag, Boom Juridische uitgevers, 2010, 589-607. 52 Case T-471/08, Ciarán Toland versus European Parliament, 7 June 2011. 53 POPELIER, P., “De openbaarheid van het overheidshandelen in een democratische rechtsstaat”, T.B.P. 1995, 707 - 715 54 Case T-233/09, Access Info Europe versus Council of the European Union, 22 March 2011. 55 F. SCHRAM, Burger en bestuur. Een introductie tot een complexe verhouding, Brussels, Uitgeverij Politeia, 20113, 142 – 172. 56 F. WEISS en S. STEINER, «Transparency as an Element of Good Governance in the Practice of the EU and the WTO : Overview and Comparison », Fordham International Law Journal, 2006, vol. 30-5, 1545 – 1586. 57 B. FRYDMAN, “La transparence, un concept opaque ? ”, Journal des tribunaux 2007/6265, 300-301. 58 M. O’NEILL, “The rights of access to community-held documentation as a general principle of EC law”, European Public Law 1998, 4(3), 403 – 432; P. SETTEMBRI, “Transparency and the EU Ligislator: ‘Let he who is without sin cast the first stone’”, Journal of Common Market Studies vol. 43 (3), 2005, p. 637-654; D. 12 ‘transparency’ and ‘openness’, others do. According to BIRKINSHAW59 and LARSSON60 where in the concept of ‘transparency’ the accent is put on simplicity and comprehensibility, ‘openness’ has to do with a mentality.61 Article 1 of the Treaty of the European Union contains the openness principle: “This Treaty marks a new stage in the process of creating an ever closer union among the peoples of Europe, in which decisions are taken as openly as possible and as closely as possible to the citizen.” It talks only about decisions and not of the full working of the European Union. The openness is intended for the citizen. 2. Freedom of Information and freedom of information laws It is very important to make a difference between on the one hand freedom of information as a concept and on the other hand the FOI-legislation that doesn’t cover necessary only freedom of information. 2.1. Freedom of information Freedom of information is used in a double sense. Often “freedom of information” is used as a synonym of access to information or access to documents, in Dutch “openbaarheid van bestuur”. It contains a legal obligation to government bodies to give access to information or documents to the public. That obligation can be a subjective right but not necessary. In principle a right of public access to information or documents exists in a passive way: people have to ask for access. The active side, the distribution of information/documents on its own initiative is only an obligation. Some scholars make rightfully a difference between ‘public access to documents’ and ‘public access to information’.62 On the one hand access to documents in their view refers to the right of individuals to request access to specific documents, on the other hand access to information implies the right to be given access to information on a given subject, what seems to imply of a more active requirement on behalf of the public authority.63 In practice the difference isn’t so sharp to be made. Looking to the Belgian FOI-legislation a document is defined as “any information that is held by an administrative authority”.64 In Dutch FOI-legislation a right access to information is granted in “information laid down in documents”.65 A document is a written piece of other material that consists out of data held by an administrative body. 66 In the first Convention on Access to Official documents of the Council of Europe, the so called CURTIN en J. MENDES, “Transparence et participation: des principes démocratiques pour l’administration de l’Union Européenne”, Revue française d’administration publique 2011, n° 137-138, 103. 59 P.J. BIRKINSHAW, “Freedom of Infomration and Openness: Fundamental Human Rights”, Administrative Law Review 2006, 58(1), 190. 60 T. LARSSON, ‘How Open Can a Government Be? The Swedish Experience”, in V. DECKMYN and I. THOMSON (eds.), Openness and Transparency in the European Union, Maastricht, European Institute of Public Administration, 1998, 40-42. 61 D. HEALD, “Varieties of Transparency”, in: Ch. HOOD and D. HEALD (eds.), Transparency: The key to better governance?, London, Oxford University Press, 2006, 26. 62 F. SCHRAM, Handboek Openbaarheid van bestuur, Brussels, Politeia, 2008, 1. A. Algemene inleiding /14. 63 E.J. DAALDER, Toegang tot overheidsinformatie. Het grensvlak tussen openbaarheid en vertrouwelijkheid, Den Haag, Boom Juridische Uitgevers, 2005, 3 – 5. 64 Article 1, second paragraph, 2° of the Law of 11 April 1994 FOI. 65 Article 3.1 of the Dutch FOI 66 Article 1a of the Dutch FOI. 13 Tromsø Convention, grants a right of access to official documents. An official document is here “all information recorded in any form, drawn up or received and held by public authorities”.67 Secondly important characteristic for freedom is information is that the right of public access to information or documents is granted without stating reasons of showing an interest. In the Flemish decree of 26 mars 2004 it is expressed clearly: the demander doesn’t have to justify an interest.68 In the Convention Tromsø you can read that an applicant for an official document shall not be obliged to give reasons for having access to the official document.69 2.2. Freedom of information and freedom of information legislation 2.2.1 Freedom of information legislation organises freedom of information In principle freedom of information legislation contains the legal rules for access to the public to information or documents. That’s the case for example in the first pillar of the Aarhus Convention, in Regulation 1049/2001 of the European Parliament and the Council of 30 May 2001 regarding public access to European Parliament, Council and Commission documents.70 The same can be said of the Dutch freedom of Information Act, the so called WOB. The regime of access is always access in abstracto, regardless the concrete person that demands for access. 2.2.2 Freedom of information legislation organises more than freedom of information But there exist freedom of information legislation that contains more than a right of public access to information/documents. Here, I will look ad two examples: the French and the Belgian legislation on access to documents. The French law, Law 78-753 of 17 July « portant diverses mesures d'amélioration des relations entre l'administration et le public et diverses dispositions d'ordre administratif, social et fiscal ». It is very important to remark that in French no word exists that is the equivalent of freedom of information. In this law three kinds of rights of access were organised. In article 6.II of this law only a right of interest and personal access is granted for administrative documents - where the communication disturbs the personal life, the medical secrecy and the secets in commercial and industrial matters; - that held an appreciation or value judgement on a physical person that is indicated by name or easily identifiable; - that contains the description of the behaviour of a person if the disclosure of that description could harm him.71 67 Article 1.2, b. of the Tromsø Convention. Article 17, § 2 of the Flemish Decree of 26 of March 2004. 69 Article 4.1 of the Tromsø Convention. 70 OJ, L. 145, 31 May 2001, 43, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/PDF/r1049_en.pdf 71 Ne sont communicables qu'à l'intéressé les documents administratifs: - dont la communication porterait atteinte à la protection de la vie privée, au secret médical et au secret en matière commerciale et industrielle ; - portant une appréciation ou un jugement de valeur sur une personne physique, nommément désignée ou facilement identifiable ; - faisant apparaître le comportement d'une personne, dès lors que la divulgation de ce comportement pourrait lui porter préjudice. 68 14 In the Belgian FOI legislation contains at the same time rules relating to public access, to interest access and to personal access to administrative documents. Because article 32 of the Belgian Constitution72 contains a rule of division of power between the federal state and the federated entities73, the different legislatures have their own FOI legislation.74 The way they make a distinction between the different forms of rights of access is almost identical. For most of them the federal law of 11 April 1994 concerning freedom of information introduces a right of interest access for “documents of personal nature”. A document of personal nature has a specific meaning: it covers an administrative document that contains an evaluation or a value judgement of a natural person who is named or can be identified or contains the description of behaviour that when it is made public can cause apparently harm to that person. 75 The other legislations on access to administrative documents have a similar, but not always the same definition. In het Flemish decree of 200476 the word ‘information of personal nature’ is used to stress that also in this case the principle of partial access has to be respected. Only for that kind of documents or information a reason must be stated. The concept of interest is not defined in most of the access to documents legislation. On federal level the Commission for access to administrative documents has very flexible interpretation. Because of the very strict definition of the notion ‘interest’ in the 2004 Flemish Decree, less people have the interest needed. Having the right interest doesn’t mean that the information becomes public. This is only the case if no exceptions can be invoked. The demand to have an interest or to show his interest is no exception, but an admissibility requirement. If someone has the necessary interest, this doesn’t mean that he or she have access to the documents he or she wants to have: the administration has to control if there are formal reasons to refuse access or if there are other interests to protect (material exemptions) Also a personal access is granted: exceptions that protect a person against disclosure of information of him cannot be invoked against the person that is protected. The privacy exemption cannot be invoked against the person whose privacy is at stake. The exemption on the protection of commercial and industrial information cannot be invoked against the undertaker that owns the enterprise and ask for access to documents with information of his enterprise. After a control of the exceptions in abstracto, a control in concreto has to be done taking into account the concrete person that demands access. It is not so that in the exemptions that are relative – exemptions where a public interest has to be done – personal interests can be taken into account. The protected interest can only be confronted with a general interest and that general interest must be more that the mere fact there exists a right of access to documents, so the general interest must be more concrete but not personal. 72 Constitutional reform of 8 June 1993, Gazette 29 July 1993, 15.584 (Article 24ter), consolidated version in Gazette 17 February 1994 (in the consolidated version, Article 24ter turned Article 32). 73 Ch. BAMPS, “Openbaarheid van bestuur. De federale wet van 11 april 1994 toegelicht”, Rec.Arr.RvS, 1996, 23; F. SCHRAM, Handboek Openbaarheid van bestuur, Brussels, Politeia, 2008, 1. A. Algemene inleiding / 40; F. ORNELIS, “Een nieuw openbaarheidsdecreet voor Vlaanderen”, in A.M. DRAYE (ed.), Openbaarheid van bestuur. Stand van zaken, Leuven, Instituut voor Administratief Recht K.U.Leuven, 1998, 13; A. ALEN and K. MUYLLE, Handboek van het Belgisch Staatsrecht, Mechelen, Kluwer, 2011, p. 676, nr. 606; E. BREMS, “De nieuwe grondrechten in de Belgische grondwet en hun verhouding tot het Internationale, inzonderheid het Europese Recht”, T.B.P. jrg. 50, 1995, 620. 74 P. LEWALLE, L. DONNAY en G. ROUSOUX, « L’accès aux documents administatifs, un intinéraire soneux », in D. RENDERS (ed.), L’accès aux documents administratifs, (Centre d’Etudes constitutionnelles et administratives 30), Brusselss, Bruylant, 2008, 57. 75 Art. 1, second al., 3° of the federal Act of 1994. 76 Gazette 1 July 2004, erratum, Gazette 18 August 2004, 62.045. 15 The result is that personal access can be asked in Belgium both on the freedom of information legislation and on the data protection legislation. But what you get is not the same. The freedom of information legislation gives the demander access to the administrative documents with information, also to information that is protected against third person because of privacy. He could get access to the source. He could look into it, ask for a copy or ask for explanation. Article 10 of the law of 8 December 1992 concerning the protection of personal data give the person concerned a right of access to the following information: - confirmation as to whether or not data relating to hem are being processed - the purpose of the processing; - the nature of the data concerned; - the origin of the data concerned; - the categories of recipients to whom the data are disclosed; - knowledge of the logic involved in any automatic processing of data concerning him The controller should communicate to the person concerned in an intelligible form of the data undergoing processing. There is no obligation for the controller to give a copy of the personal data that are processed, nor to give access to the file where the personal data can be found. In some cases the person concerned cannot exercise his right of access: - when personal data are processed for exclusively journalistic, artistic or literary purposes; - for personal data processed by security services; - for personal data processed by police; - for personal data processed by Child Focus; - for personal data processed by the Banking, Finance and Insurance Commission. 3. FOI-legislation and transparency Now we can consider the relation between the FOI-legislation and transparency and the transparency principle. 3.1 FOI-legislation can lead to more transparency but not necessary… Freedom of information and FOI-legislation are not necessary transparent and this in a triple sense: - FOI-legislation in itself is not always and not necessary transparent. An attempt to introduce in the Convention of access to official documents a right to explanation77, next to a right to consult and to be given a copy of an official document was not followed by the Group of Experts on Access to Official Documents. The lack of it was not criticized, also not by the countries that pleaded for a stronger convention. - The result of FOI-legislation is not necessary that information and documents become transparent; - The procedure to be used to obtain access to information or documents is not necessary transparent. 77 General available in the FOI-legislation in Belgium, i.e. art. 16 Although the FOI-legislation is grounded in democracy and is a key instrument in the quest for more democratic legitimacy and accountability, such legislation can also distract attention from those real “elephants in the room” such as the pervasiveness and secrecy of lobbying in the decision-making process.78 The existence of FOI-legislation can have as effect that information is not documented anymore. So information or documents cannot longer be shared by the public anymore. If this is the case, decision making can find place in for the public invisible coulisses or little corners of decision-making. 3.2 FOI-legislation contains a legal obligation, transparency is only a principle Freedom of information, in the sense of an obligation to give access to information/documents, is strongly rooted in the legal system. In the case of passive access to information or documents, it is a subjective right and in some cases it has received a place in the constitution79, even it reaches the status of a constitutional right80, or a human right.81 In some countries the right of access to documents or information is worked out as an aspect of the traditional right of freedom of expression and information; other have created a real autonomous new right.82 3.3 Most of the FOI-legislation create a legal state, transparency is only a fact The result of most of the FOI-legislation is that information or documents that falls under the scope of that legislation, is in principle open to the public. This legal presumption is the starting point of the reasoning.83 FOI-legislation changes the legal status of information. Transparency on the other hand has to do with the factual situation. It expresses an evaluation of the state of information/documents and procedures for the persons that are intended. 78 T. HEREMANS, Public Access to Documents: Jurisprudence between Principle and Practice (Between jurisprudence and recast, (Egmont Papers – 50), Gent, Academia Press, 2011, 12 – 13. 79 See for example Albania: article 23 of the Constitution of 1998; Austria: article 20, § 4 of the Constitution; Belgium: article 32 of the Constitution; Bulgaria: article 41, § 2 of the Constitution of 1991; Estonia: article 44, § 2 and 3 of the Constitution; Finland: articles 12, § 2 of the Constitution of the 1 of March 2000; Greece: article 10, § 3 of the Constitution of 1975; Latvia: article 100 of the Constitution; Lithuania: article 25(5) of the Constitution; Moldavia: article 34 of the Constitution of 1814 as amended in 2004; Norway: article 100 of the Constitution; the Netherlands: article 110 of the Constitution; Poland: article 61 of the Constitution; Portugal: article 268 of the Constitution; Czech Republic: article 17, § 5 of the Charter of rights and fundamental freedoms; Romania: article 31 of the Constitution; Slovakia: article 38 and 39 of the Constitution. 80 See for example: Belgium: article 32 of the Constitution; Estonia: article 44, § 2 and 3 of the Constitution; Poland: article 61 of the Constitution; 81 Convention on the access to official documents. See: F. SCHRAM, “The First International Convention on Access to Official Documents in the World", in A. DIX, G. FRANSSEN, M. KLOEPFER, P. SCHAAR, F. SCHOCH (ed.), Informationonsfreiheit und Informationsrecht. Jahrbuch 2009, Berlijn, Der Justische Verlag Lexxion, 2009, 21 - 56; F. SCHRAM, “From a General Right of Access to Environmental Information in the Aarhus Convention to a General Right of Access to All Information in Official Documents. The Council of Europe's Tromso Convention”, in M. PALLEMAERTS (ed.), The Aarhus Convention at Ten. Interactions and Tensions between Conventional International Law and EU Environmental Law, Groningen/Amsterdam, European Law Publishing, 2011, 67 – 89; F. EDEL, “La Convention du Conseil de l’Europe sur l’accès aux documents publics: premier traité consacrant un droit général d’accès aux documents administratifs”, Revue française d’administration publique, 2011, n° 137-138, p. 59 – 78. 82 F. SCHRAM, Handboek Openbaarheid van bestuur, Brussels, Politeia, 2008, 1. A. Algemene inleiding /32. 83 F. SCHRAM, Handboek Openbaarheid van bestuur, Brussels, Politeia, 2008, 1. A. Algemene inleiding /15. 17 3.4 FOI-legislation considers in the first place an obligation on public administrations to the public, that is not necessarily the case for transparency or the principle of transparency FOD-legislation is there in the first place for the public: it a basic form of the obligation on public authorities to give access to information or documents they held. Transparency can be intended to the public, but also only to persons with an interest or only to the concerned person. FOI is often claimed by the press and non governmental organisations. FOI-legislation is also for them, but they have no broader right of access than the public. Press and non governmental organisation cannot claim freedom of information for more than one reason. So can be remarked that the press has its proper agenda: the press wants to bring news, but not every information is considered as news. The press has also economical goals and information is selected with the intention to be sold. For non governmental organisations it often not clear who they representing and what goal they want to realize. Although press plays a very important role in a democratic society and also non governmental organisations are important for the functioning of democracy they have not right to claim freedom of information. 3.5 Transparency has another scope than the right of public access to information or documents E. CHITI emphasizes that transparency can not be reduced to the right of access to information. His remarks are specially intended for the level of the legal order of the European Union, but they also can be broadening to the national level. Within the legal order of the European Union, the principle of transparency plays a role on the legislative level, where it includes simplification and rationality of the Union and the national legislation. Secondly, the principle plays a role on the level of the division of power between the Union and the member states. Finally, it plays also a role on the level of the relations between individuals and public power, especially the right of access to information. Furthermore, CHITI accentuates that the transparency principle is realised by a great number of instruments that have as purpose to bring the citizen closer to the European Union and to make higher84 their trust in the functioning of the institutions, what is a fundamental factor of each democracy. 85 FOI-legislation can contribute to more transparency, but it has its own dynamic as a set of legal rules and as fundamental and human right. Transparency can contribute to access to information and documents. 84 E. CHITI, "The Right of Access to Community Information under the Code of Practice: the Implications for Administrative Development", European Public Law 1996, 370. 85 D. CURTIN en H. MEYERS, « Scrutiny. The principle of open government in Schengen and the European Union: democratic retrogression", Common Market Law Review 1995, 390 - 442. 18 4. To a more effective content for the concept of transparency and the principle of transparency Although I do not contest that the concept of transparency functions within a democratic society and the study of how it functions is very appealing, it is preferable from a scientific point of view to work with a more clear defined term. 4.1 Transparency as a factual state A lot of descriptive definitions of transparency are formulated in terms of the means that are used. The means are not necessary transparent. It is more useful to reserve transparency to the factual state. Is a process transparent? Is information transparent? Is legislation transparent? Is the legal system transparent? But the means in itself are not necessary transparent. 4.2 Transparency as a principle of governance Transparency can also be used as a driving principle founded in democracy and democracy theory. That principle needs to be concretised and each concretisation has to be evaluated in what way it can be called to be transparent. Transparency as a principle of governance can not be the final goal, but it is an instrument to realise democracy. Democracy is not only as a political system where the power goes out from the people but it a society where everyone can maximalize his own development in freedom with and through others. A democracy is not only reserved to the political system, but can be extended to the whole society: therefore the principle of transparency can be used in different contexts, not only in the context of public authorities. But transparency will always leave open a few questions that had to be filled in: what has to be or has to be made transparent, for whom must it be transparent, who has to make something transparent, when has something to be transparent. In a society that is growing more and more towards an information society, the equal access to intelligible information, open processes and Transparency is more and more seen as a principle of good governance, a set of non legal binding principles86 instead of principles of good administration, but principles that give guidance for the functioning of public administration. 4.3 Transparency as a general legal principle Transparency can also be growing out to a legal principle for public action. A legal principle means that the principle has legal results. It should contain a number of objective quality criteria for organising and for control and check public actions. G.H. ADDINK, “Principles of Good Governance, Lessons from Administrative Law”, in: D.M. CURTIN and R. WESSEL (eds.), Good Governance and the European Union. Reflections on concepts, institutions and substance, Antwerp-Oxford-New York, Intersentia, 2005, 21 – 48; G.H. ADDINK, Over Algemene beginselen van goed bestuur en het transparantiebeginsel, in Th.G. Drupsteen e.a. (red.) Weids Water, Den Haag, Sdu, 2006, 255-282; G.H. ADDINK, Goed bestuur: een norm voor het bestuur of een recht van de burger?, in: G.H. ADDINK, G.T.J.M. JURGENS, Ph. M. LANGBROEK en R.J.G.M. WIDDENSHOVEN (ed.), Grensverleggend bestuursrecht, Alphen aan den Rijn, Kluwer, 2008, 3- 25; G.H. ADDINK, Goed bestuur, Deventer, Kluwer, 2010, 147 p. 86 19 The term public action should not be limited to actions of the public sector but should extend to all actions that have an importance for the society. Decisions of private sector should for that reason also be transparent if these decisions touch society. 4.4 Transparency as an ethical value and as an aspect of integrity Transparency is also an ethical value and an aspect of integrity. Ethical values function in a different way of legal principles and principles of good governance. An ethical value has a appeal function for individual and collective actions. 4.5 Transparency is no goal in itself Transparency and the principle of transparency cannot be a goal in itself. If transparency become a goal in itself, there is a risk that it could in the end trump its own “raison d’être”. Too much transparency can kill transparency by triggering a variety of evasive practices. 87 The cry for more transparency is based upon a number of unproven normative assumptions. One of them is: the more transparency the better. Transparency can give as a result that no decisions are taken. That’s particular the case where a consensus-type of decision making is used. It doesn’t take into account that cultural elements play a role. Transparency is not a goal in itself, but has to be seen without a democratic society, where a lot of principles, rights and interests have their place. 5. Conclusion Transparency, freedom of information, access to documents, access to information, openness, … a lot of words that are used in different situations and sometimes mean the same, sometimes have a specific means. In the existing literature it’s no clear what they mean exactly. This doesn’t mean that these terms don’t play a role. Recently more interest is shown to the way some of these terms function. First we have explored the concept of transparency and its use. We did also the same for the concept of freedom of information. Afterwards we paid attention to the differences between the two concepts and finally we have tried to formulate how transparency and the principle of transparency can be used in the legal system in a more proper way: as a factual state, as a principle of good governance, as a legal principle and as an ethical value and an aspect of integrity. It is no goal in itself but has to be seen in a concrete political, legal, institutional and cultural setting of a democratic society. 87 T. HEREMANS, Public Access to Documents: Jurisprudence between Principle and Practice (Between jurisprudence and recast, (Egmont Papers – 50), Gent, Academia Press, 2011, 12.