Appendix 2 - Documents & Reports

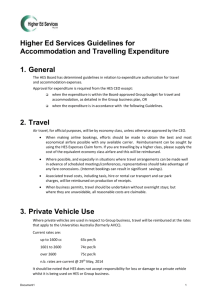

advertisement