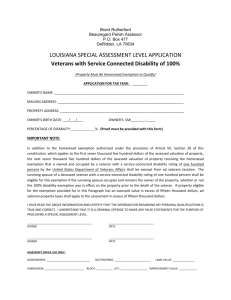

DOC - Craig Law Office

advertisement

1

A “Rogue’s Paradise?”

A Review of South Dakota’s Property Exemptions and a Call for Change

By James A. Craig1

PRELUDE

This article explores South Dakota’s property-exemption statutes, their history, and

recent case treatment. The philosophy of a person’s relation to the state, as well as the

competition between the interests of capital and those of debtors will be discussed briefly. After

discussing the historical context and competing interests in this area of the law, I will argue that

changes need to be made to comply with the South Dakota constitution’s requirement that the

comforts and necessaries of life shall be recognized by wholesome laws exempting from forced

sale a homestead and a reasonable amount of personal property.

I.

How Did We Get Here?

The story of South Dakota’s property-exemption statutes is necessarily historical as the

statutes have changed little since territorial days.

It wasn’t until 1859 that a permanent

settlement took root in Yankton, the “Mother City of the Dakotas.”2 Dakota Territory was

created in 1861 (the year the civil war began).3 It was split into the states of North Dakota and

South Dakota in 1889,4 and our state undertook the process of creating the constitution and

statutes by which it would govern.

A.

1

A Nation In Crisis: The Panic of 1873 And The Political Climate That

The author is a sole practitioner in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. He was a bankruptcy trustee for 10 years

and is a past president of the National Association of Bankruptcy Trustees. He formed the South Dakota State Bar

Association’s Debtor Creditor Committee, serving as its Chairman and as a member at various times over 30 years.

The author wishes to thank his daughter, Amy Henson, for her valuable editorial assistance in the

production of this article.

2

Robinson, Doane, History of South Dakota, 1904 B.F. Bowen & Co., p. 2.

3

Act of March 2, 1861, Ch. 86, 12 Statutes At Large 239.

4

Act of February 22, 1889, Ch. 180, 25 Statutes at Large 676.

2

Followed

As the infant state of South Dakota began setting out its constitution and laws, it was, of

course, impacted by events of the times. Primary among these was the so-called economic panic

of 1873. In 1873, a major economic downturn spread from Europe to the United States. It was

precipitated on this side of the pond by unregulated industrial growth and the fall of Jay Cooke

and Company, the country’s preeminent investment banking firm and principal backer of the

Northern Pacific Railroad. Jay Cooke, acting in an era of wide-spread American political

corruption, obtained numerous government subsidies for the railroad by bribing politicians and

lying shamelessly about the qualities of the northern plains.5

In the summer of 1873, however, the money market tightened as congress began

withdrawing paper money from circulation under a concern that it posed a danger to society. “It

was in this context that Jay Cooke, no longer able to get loans, began using his clients' money

without bothering to tell them.”6 By September of 1873, Cooke had depleted most of his bank’s

resources.7 Jay Cooke and Company, along with other banks in the nation, had no place to turn.

The result was a “domino effect,” explained by author Michael Bellesiles as follows:

Without a central bank capable of protecting businesses and the stock

market from the mass recall of loans, banks had no security against sudden runs

on their resources. As a consequence, the whole financial structure experienced a

domino effect, as first one business and then another toppled, knocking over those

linked to each collapsing enterprise. President Grant and Congress stood by

Bellesiles, Michael A., 1877 America’s Year of Living Violently, 2010, The New Press, New York, pp 2-7.

Id.

7

Id.

5

6

3

helplessly and watched.8

During the resulting “panic,” the New York Stock Exchange closed for 10 days, credit

dried up, banks failed, and foreclosures were frequent.9 Eventually, many factories closed and

thousands of workers lost their jobs. Understandably, there developed from the panic a “bitter

antagonism between workers and the leaders of banking and manufacturing.”10 This antagonism

set the stage for labor disputes in the years that followed.

In 1877, railroad owners cut workers’ wages to starvation levels, leading to the first

nationwide strike in American history.11 The “Great Strike of 1877” began in West Virginia and

quickly spread across the country, as over five-hundred-thousand railroad workers left their jobs

and disrupted freight and passenger traffic.

As Bellesiles explains:

Management responded to these events not with negotiation but with

force. When local and private police forces proved insufficient to compel the

workers to return to work, management turned first to the state militia, and then to

the United States Army (corporate leaders expected their voices to be heard and

heeded at all levels of government, and they were rarely disappointed).12

The events accompanying the Great Strike led Bellesiles to describe 1877 as one of the most

violent years of the nation’s history.13

Dakota Territory, of course, was not exempt from the effects of the economic panic—nor

the violence that followed it. The territory was cursed with high interest rates, sanctioned under

8

Id.

http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h213.html, last accessed 9/16/2013.

10

http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h213.html, last accessed 9/16/2013.

11

Bellesiles, Michael A., 1877 America’s Year of Living Violently, 2010, The New Press, New York, pp 29

7.

12

13

Id. at 145.

Id. at ix.

4

the ostensible goal of attracting capital to the territory.14

The prevailing rate for chattel mortgages was ten per cent. Real estate

mortgages, however, commanded whatever rates the traffic could bear. The

maximum legal rate under legislation enacted in 1871 was two per cent a month

or 24 per cent a year. In 1873 the maximum rate was fixed at 18 per cent.

Approximately one-half of the real estate mortgages recorded in Clay

County during 1872 stipulated interest at 24 per cent. . . . The Legislature in 1875

complied with popular demand for a revision of the usury law by fixing 12 per

cent as the legal rate, but this reduction only mitigated some of the worst features

of the credit system.15

Given the national temperament, it is no surprise that Dakotans responded violently in

1877, when they learned that legislators of Dakota Territory repealed their personal-property

exemptions. Former South Dakota state historian Doane Robinson relates:

A bill, introduced by Mark W. Sheafe, providing that the conveyance of a

homestead should be absolutely invalid unless the wife joined in the conveyance,

was passed with a considerable modification in the house. Shortly after the close

of the session Hon. S. L. Spink was checking up his volume of the statutes by the

enactments of the recent legislature when he discovered that one section of the

new homestead law repealed the personal property exemption law of 1862, and as

he interpreted it, left the settlers without any personal property exemption

whatever. He at once called public attention to this repeal and it is probable that

no other event in the history of Dakota territory created such a sensation as did

this. Everybody was in debt and the repeal of the exemption law exposed all of

their property to execution sale. An indignation meeting assembled and was

addressed by many of the leading citizens of the territory. Spink, Brookings,

Bartlett Tripp16, Beadle, Hand, Burleigh and others made exciting talks upon the

subject. Dr. Burleigh expressed the sense of the meeting when he said, "To get up

some morning and find that several of Dakota's counties had been suddenly

swallowed up by an earthquake would be of but passing consequence to me when

compared to the surprise and indignation occasioned by the discovery of the

passage of this bill repealing the personal property exemptions." An examination

of the subject developed the fact that Mr. Sheafe's bill, as originally introduced,

contained but three short sections providing specifically that the wife must join in

the conveyance of the homestead. That in its passage through the house the bill

was amended and re-drafted by Colonel Moody, who extended it into nineteen

14

Shell, History of South Dakota, UNP, 1961, pp 122-123. Official immigration pamphlets issued in 1870

and 1872 called special attention to the advantages of high interest rates. Id.

15

Id.

16

Bartlett Tripp was later elected the first president of the South Dakota Bar Association in 1897.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bartlett_Tripp, last visited 6/19/2013.

5

sections, defining a homestead and prescribing the method by which it could be

claimed and exempted from execution. One of the last of these sections provided

that a section of the exemption law of 1862 should be repealed. The public at

once jumped to the conclusion that there was a conspiracy between Moody,

Sheafe, Jolley and others to deprive the people of their exemption rights in the

interest of the money sharks, and after the public meeting had abused them to

their heart's content the excited crowd went out and hung Moody, Sheafe and

Jolley in effigy.17

Members of the indignation meeting directed territorial governor John Pennington to go

to Washington and convince the United States Congress to revoke the act passed by the

territorial legislature.18

Governor Pennington was successful in his task, but the incident

nonetheless “had spread concern and perturbation throughout the territory.”19 Robinson has

astutely recognized, “It is hard now to comprehend fully how vital the exemption law was to the

debt ridden settlers of [the time]. In fact the very existence of many of them depended upon it,

and it would have been a courageous man indeed who should knowingly have voted for this

abrogation. . . .”20

In addition to the short-term elimination of the personal-property exemption, early

Dakotans had to endure the appointment of governors whom they viewed as corrupt.

For

example, they bristled at their treatment at the hands of political hacks like Nehemiah Ordway,

appointed as governor of Dakota Territory in 1880. Ordway used the office to profit at the

expense of the settlers. He “bribed legislators, threatened vetoes of legislators’ bills if they

resisted his plans, compelled settlers seeking county seats to give him land, installed his son as

17

Robinson, Doane, The History of South Dakota, pp. 265-266. In his defense, Colonel Moody made the

argument that “the law of 1862 had been enlarged upon by a law in 1866, which was whole and complete in itself,

and therefore the exemption law was not repealed nor in any wise affected, but no one of the other lawyers agreed

with him.” Id.

18

Id.

19

Id.

20

Id.

6

territorial auditor in order to control finances, and moved the capital from Yankton to Bismarck

in order to benefit from real estate speculation.”21 This was the political climate that existed

when the state of South Dakota was born.

B.

Constitutional Development

South Dakota’s constitution states:

The right of the debtor to enjoy the comforts and necessaries of life shall

be recognized by wholesome laws exempting from forced sale a homestead, the

value of which shall be limited and defined by law, to all heads of families, and a

reasonable amount of personal property, the kind and value of which to be fixed

by general laws.22

How these homestead and personal-property exemptions came about is important in

considering how they should be interpreted today. Although South Dakota’s constitution was a

product of conventions running from 1883 to 1889, the most significant discussion of property

exemptions occurred on the sixteenth day of the 1885 convention. On that day, the debate

centered on what protections should be afforded creditors and debtors, whether the constitution

or future legislation should set exemption amounts, and the persons to whom the exemptions

should apply (i.e.,whether to include the reference to “heads of families”).

First, the convention members addressed the balance to be struck between protecting

debtors and attracting business. The interests of those wishing to attract capital to the state

conflicted with those concerned about protecting a debtor and his family. Mr. Fowler laid out

the position of those whose aim was to bring capital to the state:

Lauck, John “The Organic Law of a Great Commonwealth”; The Framing of the South Dakota

Constitution, South Dakota Law Review, vol.53, p225, 2008.

22

South Dakota Constitution Art. XXI §4, adopted October 1, 1889.

21

7

I dislike to have the homestead limited to two-thousand dollars, first

because it might catch me but laying that aside, sir, I think that proposition of

one-thousand dollars invested in a homestead, is probably a little small; in other

words, if a man, the head of a family, in the business of agriculture, happens to be

unfortunate, unable to pay his debts, if he has a comfortable home for his family, I

should very much dislike to have him turned out of doors because it exceeded

one-thousand dollars. On the other hand, the minority report suits me better than

the majority report, it fixes the value beyond which the legislature can not go. My

experience in Dakota is, that the exemption laws prevents parties from collecting

debts that are due to him but they injure the credit of every inhabitant in Dakota. .

. . I move to substitute the word five-thousand for two-thousand, providing there

shall be no exemptions allowed to any except the heads of families.23

Mr. More then laid out the view that the constitution should protect the debtor and his family:

I think an honest endeavor to get at the real purpose of exemptions may

come in here. I do not think that the legislature intends that cheating creditors is

the object of exemptions. I think the real object of exemptions is that the family

may not be dispersed and financially wrecked but what they can prosecute the

industries in which they have engage, so that subsequently they can pay their

debt. It is a fact that creditors are sometime avaricious; it is a fact that some

creditors seems to take it all; and when they do take it all; the family from which

they take it away, are financially wrecked.” 24

Eventually Mr. More’s position prevailed, leading Mr. Jones of Miner to excitedly

exclaim, “This is a rogue’s paradise!”25

Second, the convention members debated whether exemption amounts should be firmly

set in the constitution or whether they should be left to the legislature to set. Delegate distrust of

future legislatures is a recurring theme in the debates. No doubt this was a reflection of general

distrust in government given the national abuse reflected in the scandals of the age by moneyed

interests. Some delegates favored enacting a strict constitutional limit on future legislatures to

protect the credit of South Dakota. Others insisted the constitution should be a broad expression

of policy, with the legislature determining the specifics, as required at any given time. In the

23

Constitutional Debates, 1885 session, sixteenth day, p. 552.

Id. at p. 555.

25

Id. at p. 559.

24

8

end, the delegates adopted the recommendation of the Committee on Exemptions Real and

Personal, leaving the amount to be set by the legislature:

Mr. Allen of Turner County (member of the Committee on Exemptions

Real and Personal appointed in 1883) explained the committee had adopted the

article in view from Wisconsin, “thinking it would answer the purpose for Dakota

just as it would for Wisconsin. It exempts simply the homestead, and leaves the

legislature to determine its value; whatever they may determine is the reasonable

value to place upon the homestead, it will so remain. We thought it going too

much into legislation for this Convention to fix that amount. It also exempts a

reasonable amount of personal property, it does not state the amount; we think the

necessity for exemptions is liable to change at any time; what may be a reasonable

exemption of personal property today in ten or twenty years from now may be

very unreasonable. So it was thought to leave this matter entirely to the

legislature and let them fix the amount of exemptions, real and personal, as they

think the people demand. The Legislature come directly from the people and they

will know just exactly what they want. We are of the opinion that this matter

ought to be left entirely to the legislature.”26

Finally, the delegates addressed the important question whether the exemptions should be

limited to “heads of family,” and, if so, what was meant by that phrase.

The issue was

complicated by the fact that the territorial code referenced only “debtor.”27

Mr. Fowler

explained his belief that the exemptions should be denied single men, whom he did not consider

“heads of families”:

If the minority report is adopted I should feel like adding a provision to it

to comply with the provision of the majority report, so that it should include only

the heads of families. I don’t believe in including in exemptions those great

able-bodied men who have got nothing to do but take care of themselves. A man

who is able-bodied and wants the benefit of this statute ought to emigrate from

this country, he ought to be ashamed of being in this country, and nobody but a

booby28 would expect to do it.29

Shortly thereafter, the delegates were asked to consider an amendment to the report of the

26

Id. at p. 554-55 (remarks of Mr. Gehon).

See Historical summary addendum.

28

Webster defines “booby” as, “an awkward foolish person: dope.” Webster’s Third New International

Dictionary 252 (1981).

29

Constitutional Debates, 1885 session, sixteenth day, p. 552.

27

9

majority committee, which amendment would have deleted the reference to “heads of families.”

Mr. Neill: I now insist upon my motion that we adopt the report of the

Majority Committee.

Mr. ————: I desire to offer an amendment. . . . I desire to strike out in

the third line the words “heads of families”, and the reason why I want that done

is because it is not now consistent with Sections 10 and 12 of the report, which

says that no special immunity shall be granted to any person or corporation. . . .

By the President: The first motion is on the adoption of the majority

report, offered by Mr. Neill, of Grant. The gentleman from Lawrence proposes an

amendment in reference to the heads of families. . . .

Mr. Dow: I think we have covered a large range of discussion, and I am in

favor of leaving something to the Legislature. I do not believe it is necessary for

us to prescribe all limits, and for that reason I would favor the original report of

the majority Committee; but I will say this; that I believe large exemptions are

detrimental to a poor man instead of money loaners. This I believe every man

who handles money will agree with me, that large exemptions are to the

disadvantage of the poor man. I want to say while I am on the floor that I am

opposed to that amendment, which would throw around the married man the

protection of the State of Dakota I believe that the man who has no wife is to be

pitied, and he is entitled to the sympathy of the State. A man that has a wife is

worth $1000 without any other property, and every child about $500, and I am

opposed to the amendment of the gentleman from Lawrence, which makes this

distinction, and think it would be better to leave this matter to the legislature, and

let them decide the matter. Therefore, I oppose this amendment, and favor the

majority report.

Mr. Frank: I would like to say in answer to the gentleman from Brown

county, that I am a poor man, and am trying to accumulate some property to get

married.

Mr. Owen: Mr. President, I would like to ask if this Constitutional

Convention in adopting this, prescribes the limitations, in providing for

exemptions for heads of families, does it by implication, so far as the right of the

Legislature to deny the right to anybody else, so that the poor single wretch might

be deprived of his goods.

Delegate: It is not meant by this that a man must marry as soon as the sign

runs out.

By the President: The question is upon the motion of Mr. Franks which is

to strike out the words “of families.”

10

The vote stood 29 for and 39 against, the amendment is beaten.30

Thus, by eleven votes, the issue of who is “head of the family” would be litigated for

decades to come.

Living Under 19th Century Standards in the 21st Century: The Current State of South

II.

Dakota’s Exemption Statutes

A. The Statutory Framework

The first property exemption provision was placed in Chapter 37 of the Territorial Code

of 1862. In eleven succinct sections, Chapter 37 defined the homestead and personal property

exempt in the territory. A summary is found in the historical chart appended to this article.31 It

is noteworthy that it made no distinctions among debtors, such as “head of family,” “single

person,” or “non-head of family.” It also contained no arbitrary categories of personal property,

such as “absolute,” “additional,” or “alternative property”. It contained generous (by today’s

standards) provisions protecting the debtor from the elements, i.e. food, clothing, and provisions

for a year. It permitted the debtor to keep property necessary to get back on his feet, including

tools and a mode of transportation in all seasons. Over the years we have strayed from these

concepts.

In 1877, Dakota Territory categorized property exemptions as absolute,32 additional,33

and alternative,

34

an approach that was codified at South Dakota Codified Laws Title 43,

Chapter 45. A historical chart attached to this article35 traces what became of those provisions

over the years, and provides a perspective of the value of the exemptions by converting the dollar

30

Id. at pp. 559-61.

See Addendum 1.

32

S.D.C.L. 43-45-2.

33

S.D.C.L. 43-45-4.

34

S.D.C.L. 43-45-5 (repealed by SL 1998, ch 265, § 2.)

35

Addendum 1, supra.

31

11

limitations at the time of passage to 2012 values, using the consumer price index as the measure

of value.36 South Dakota codified the homestead exemption at South Dakota Codified Laws,

Title 43, Chapter 31.

Later, other property exemptions were added to the code and were located outside of

Title 43. Annuities,37 fraternal benefit society benefits,38 health insurance,39 life insurance,40

retirement benefits for municipal41 and public42 employees, unemployment compensation,43 and

worker’s compensation benefits44 are found elsewhere. In 2011, the state bar’s Debtor Creditor

Committee worked with the code’s editors at Thomson Reuters to list (for the first time) all of

these provisions in the index under Debtors and Creditors, Exempt property. 45

In addition, exemptions not found in South Dakota’s code will apply to South Dakota

debtors from time to time. Federal statutes are included in statutes governing Social Security

benefits;46 disability and death compensation to federal employees; 47 Civil Service retirement

annuity payments;48 serviceman’s savings, pensions, and military survivor’s benefits;49 Federal

Home Loan Mortgage Corp benefits;50 Foreign Service Retirement benefits;51 Judicial Survivor

36

http://www.measuringworth.com/U.S.C.ompare/ last visited 7/2/2013.

S.D.C.L. 58-12-6.

38

S.D.C.L. 58-37A-18.

39

S.D.C.L. 58-12-4.

40

S.D.C.L. 58-12-4 (and 43-45-6).

41

S.D.C.L. 9-16-47.

42

S.D.C.L. 3-12-115.

43

S.D.C.L. 61-6-28.

44

S.D.C.L. 61-6-48.

45

General Index A-L, pp. 680-681.

46

42 U.S.C. 407.

47

5 U.S.C. 8130.

48

5 U.S.C. 8346.

49

10 U.S.C. 1035, 1440, and 1452.

50

12 U.S.C. 1452.

51

22 U.S.C. 4060.

37

12

benefits;52 Serviceman Veteran’s Group Life Insurance benefits; 53 war risk hazard benefits;54

Railroad Retirement benefits and railroad workers unemployment benefits;55 and CIA Employee

Retirement benefits.56

Finally, a bankruptcy practitioner must utilize the exemption statutes of the state in which

her client resided 730 days prior to filing the bankruptcy case or, if the debtor was domiciled in

more than one state during that 730-day period, the state in which the debtor was domiciled for a

longer portion of the 180-day period immediately preceding that 730-day period than in any

other state.57 and occasionally, the federal bankruptcy exemption provisions,58 when application

of a state’s exclusion of exemptions to non-residents, would otherwise leave a debtor with no

state exemptions.

1. Absolute Exemptions

As of July 1, 2013, S.D.C.L. § 43-45-2 reads:

The property mentioned in this section is absolutely exempt from all such

process, levy, or sale, except as otherwise provided by law:

(1) All family pictures;

(2) A pew or other sitting in any house of worship;

(3) A lot or lots in any burial ground;

(4) The family Bible and all schoolbooks used by the family, and all other

books used as a part of the family library, not exceeding in value two hundred

dollars;

(5) All wearing apparel and clothing of the debtor and his family;

52

28 U.S.C. 376n.

38 U.S.C. 770.

54

42 U.S.C. 1717.

55

45 U.S.C. 231.

56

50 U.S.C. 403.

57

11 U.S.C. §522(b)(3)(a). State exemptions can be found in bankruptcy treatises, such as the National

Consumer Law Center’s Consumer Bankruptcy Law and Practice, 10 th edition, 2012, Vol 2., Appendix J.

58

11 U.S.C. §522(d).

53

13

(6) The provisions for the debtor and his family necessary for one year's

supply, either provided or growing, or both, and fuel necessary for one year;

(7) All property in this state of the judgment debtor if the judgment is in

favor of any state for failure to pay that state's income tax on benefits received

from a pension or other retirement plan while the judgment debtor was a resident

of this state;

(8) Any health aids professionally prescribed to the debtor or a dependent

of the debtor.59

Sections (1) through (6) have been on the books since 1877. Considering the year they

were created, they were reasonable. What about now? Does any family provide their own pew

in today’s churches? The bible and schoolbooks were allowed in an amount that equals $4,520

of today’s dollars. Yet, $200 is still on the books. How do we learn today? If limited to a bible

and schoolbooks, how would debtors and their dependents compete with peers using computers,

ipads, smart phones, calculators, nooks and kindles, not to mention television and radio?

Provisions for one year’s supply and fuel necessary for a year was understandable in an agrarian

society, in which a family’s crops could be wiped out by the elements. In that time there was no

social safety net, other than churches and charitable neighbors. Today’s farmers have crop

insurance and subsidized loan programs. Others have state assistance in the form of food

stamps, heating and rent assistance, and social security benefits. The problem is, no one has

taken a look at these statutes in a very long time. If we are to maintain an absolutely exempt

division of property, what should it include today?

2.

Additional Exemptions

As of July 1, 2013, S.D.C.L. § 43-45-4 provides:

In addition to the property provided for in §§ 43-45-2 and 43-45-3, the

debtor, if the head of a family, may, personally, or by agent or attorney, select

from all other of the debtor's personal property, not absolutely exempt, goods,

chattels, merchandise, money, or other personal property not to exceed in the

59

SL 2013, §1.

14

aggregate seven thousand dollars in value; and, if not the head of a family,

property as aforesaid of the value of five thousand dollars, which is also exempt,

and which shall be chosen and appraised as provided by law.

In Section II C, you will see many cases dealing with “head of a family” vs. “single

person” or “not the head of a family.” Understand, this is the legacy left us by at least eleven

constitutional delegates at the end of a long day, who ignored the sound advice of the un–named

delegate who urged them to drop the distinction because it was not consistent with “Sections 10

and 12 of the report, which says that no special immunity shall be granted to any person or

corporation.”

The supreme court has ruled that the legislature may define these terms. 60 Indeed, with

respect to homestead provisions, it did so in 1903, saying that any family, whether consisting of

one or more persons shall be deemed to be a “family” with respect to homesteads. S.D.C.L. 4331-14.61 Because the legislature never did the same thing with respect to personal property

exemptions, we remain mired in this quagmire with respect to personal property.

By far the single greatest failing of the legislature is to link the dollar values to the

consumer price index providing an automatic adjustment by law. In an area of the law where

decades (or a century) pass with no meaningful review of a statute by the legislature, this is

inexcusable. Minnesota and the U.S. Congress have done this. It’s time for South Dakota to

follow suit.

B.

60

Some Thoughts Before Examining Our Local Case Law; or Pigs, Hogs, and the

The homestead right, however, within constitutional limitations, is one clearly a matter of legislative

discretion, and may be conferred upon any person or class of persons of its own choosing. Where the right is

conferred upon the head of a family, it may declare who shall be considered the head of a family. Where it is

conferred upon the family, it may declare of whom the family shall consist. As is said in Wales on Homestead and

Exemption (page 98, par. 11): “The true rule is, Follow the statute.” Sobers v. Sobers, 1914 33 S.D. 551, 146 NW

716, 718; on rehearing 34 S.D. 594, 149 NW 558.

61

SL 1874-5, ch 37, §2, Hesnard v. Plunkett, 1894, 6 S.D. 773, 60 NW 159; In re Hanson, (Bkrtcy SD, 17

B.R. 239).

15

“Length of the Chancellor’s Foot”.

Before considering case law dealing with exemptions, remember that much depends upon

the trier of fact’s view of the case. Just as the tension between creditors and debtors was seen in

the constitutional delegates’ remarks, it is seen in the remarks of judges and particularly

bankruptcy judges. In 1988, two Eighth Circuit decisions were issued on the same day, by the

same panel. In each, the lower court’s ruling was upheld, though one court disallowed the

exemption (and the debtor’s discharge), while the other court allowed the exemption.

In Northwest Bank Nebraska, N.A. v. Tveten,62 a Minnesota physician in financial trouble

liquidated assets and invested the proceeds in a homestead having a value of some $700,000.00.

Minnesota had no dollar limit on the homestead at that time.

In Hansen v. First National Bank in Brookings,63 a South Dakota farmer sold property at

fair market value to family members and invested the proceeds in a life insurance policy, exempt

under South Dakota law. In his concurring opinion in Hansen, Judge Arnold provided an astute

analysis of these decisions:

I agree with the result reached by the Court and with almost all of its

opinion. I write separately to indicate some variation in reasoning and also to

compare this case with the companion case of Norwest Bank Nebraska, N.A. v.

Tveten, 848 F.2d 871, also decided today by this panel.

In general, as the Court says, citing Forsberg v. Security State Bank, 15

F.2d 499 (8th Cir.1926), "a debtor's conversion of non-exempt property to exempt

property on the eve of bankruptcy for the express purpose of placing that property

beyond the reach of creditors, without more, will not deprive the debtor of the

exemption to which he otherwise would be entitled." Ante, at 868. And this is so

even if the conversion of property into exempt form takes place while the debtor

is insolvent. The result is otherwise, of course, if there is "extrinsic evidence of

fraud," ante, at 868, but the word "extrinsic" must mean some evidence other than

the conversion of the property into exempt form itself, the debtor's insolvency,

62

63

Norwest Bank Nebraska, N.A. v. Tveten, 848 F.2d 871(C.A.8 (MN.), 1988).

Hanson v. First Nat. Bank in Brookings, 848 F.2d 866 (C.A.8 (S.D.), 1988).

16

and the debtor's purpose to put the property beyond the reach of creditors.

Otherwise, the entire Forsberg rule would be swallowed up in the exception for

"extrinsic fraud."

The Court is entirely correct in holding that there is no extrinsic fraud

here. The money placed into exempt property was not borrowed, the cash

received from the sales was accounted for, and the property was sold for fair

market value. The fact that the sale was to family members, "standing on its own,

does not establish extrinsic evidence of fraud." Ante, at 869.

With all of this I agree completely, but exactly the same statements can be

made, just as accurately, with respect to Dr. Tveten's case. So far as I can tell,

there are only three differences between Dr. Tveten and the Hansons, and all of

them are legally irrelevant: (1) Dr. Tveten is a physician, and the Hansons are

farmers; (2) Dr. Tveten attempted to claim exempt status for about $700,000

worth of property, while the Hansons are claiming it for about $31,000 worth of

property; and (3) the Minnesota exemption statute whose shelter Dr. Tveten

sought had no dollar limit, while the South Dakota statute exempting the proceeds

of life-insurance policies, S.D.Codified Laws Ann. Sec. 58-12-4 (1978), is limited

to $20,000. The first of these three differences--the occupation of the parties--is

plainly immaterial, and no one contends otherwise. The second--the amounts of

money involved--is also irrelevant, in my view, because the relevant statute

contains no dollar limit, and for judges to set one involves essentially a legislative

decision not suitable for the judicial branch. The relevant statute for present

purposes is 11 U.S.C. Sec. 522(b)(2)(A), which authorizes debtors to claim

exemptions available under "State or local law," and says nothing about any

dollar limitations, by contrast to 11 U.S.C. Sec. 522(d), the federal schedule of

exemptions, which contains a number of dollar limitations.) The third

difference--that between the Minnesota and South Dakota statutes--is also legally

immaterial, and for a closely related reason. The federal exemption statute, just

referred to, simply incorporates state and local exemption laws without regard to

whether those laws contain dollar limitations of their own.

The Court attempts to reconcile the results in the two cases by

characterizing the question presented as one of fact--whether the conversion was

undertaken with fraudulent intent, or with an intent to delay or hinder creditors. In

Tveten, the Bankruptcy Court found fraudulent intent, whereas in Hanson it did

not. Neither finding is clearly erroneous, the Court says, so both judgments are

affirmed. This analysis collapses upon examination. For in Tveten the major

indicium of fraudulent intent relied on by the Bankruptcy Court was Dr. Tveten's

avowed purpose to place the assets in question out of the reach of his creditors, a

purpose that, as a matter of law, cannot amount to fraudulent intent, as the Court's

opinion in Hanson explicitly states. Ante, at 868. The result, in practice, appears

to be this: a debtor will be allowed to convert property into exempt form, or not,

depending on findings of fact made in the court of first instance, the Bankruptcy

Court, and these findings will turn on whether the Bankruptcy Court regards Page

871 the amount of money involved as too much. With all deference, that is not a

rule of law. It is simply a license to make distinctions among debtors based on

17

subjective considerations that will vary more widely than the length of the

chancellor's foot.64

C. Review of South Dakota Bankruptcy Court decisions.

Bankruptcy practitioners can refer to local precedent by going to the court’s website. 65

The case notes below are intended to aid practitioners in their research, once they get to the

court’s site.

EXEMPTIONS - ANNUITIES

McGruder, John David & Marlene Joyce 2001 #34

This annuity not a trust; Present value analysis rejected by court under S.D.C.L. 58-12-8.

Three future payments added and divided by months covering period. Debtor entitled to $250

per month, balance to estate.

Powell, Susan M. 2006 #19

Conversion of cash into annuity (not in payment status) on eve of filing not fraudulent;

exemption allowed. 58-12-6 limited only by 7, 8, and 9;not subject to 54-8A-4.

EXEMPTIONS - AVOIDANCE OF LIEN ON EXEMPT PROPERTY

Aguire, Antonio & Kelli D. (Aguirre v. Fullerton Lumber) 2007 #5.

11 U.S.C. 348 doesn’t turn conversion date into new petition date for purposes of

547(b)(4); as homestead was no longer property of the estate once deadline for objecting to

exemption had passed (FRBP 4003(b)), and as Fullerton’s work and mechanic’s lien never

attached to estate property and it filed no claim in bankruptcy, 11 U.S.C. 502 and 506 have no

effect. Though the homestead exemption is at all times and under all circumstances not subject

to a lien, judgment or levy and sale under execution, except for purchase money (citing In re

64

65

These cases stand for the proposition that, “Pigs get fed, and hogs get slaughtered.”

http://www.sdb.U.S.C.ourts.gov/Decisions.

18

Maiden Mills, Inc. 35 B.R. 71 and Langley v. Daly, 1 S.D. 257, 46 NW 247(1890)), the issue of

whether Fullerton’s claim is protected from debtor’s claim of exemption (under S.D.C.L. 43-458) as material furnished in the original erection of the homestead, is to be determined by the state

court.

Hamann, David R. & Peggy J. 1997 #32

Purchase money security interest in furniture is not merged into a money judgment, citing

In re Hogg, 76 B.R. 735,741-742(Bankr.S.D.1987). Judgment and security interest co-exist. 11

U.S.C. 522(f) can not be used to void purchase money security interest.

Heikes, JoAnne 1997 #4

Possessory lien survives debtor’s motion for avoidance under 11 U.S.C. 522(f).

West, Jesse & Luella 2000 #42

Court rejects legal fiction that filing bankruptcy petition creates “sale of homestead”

thereby limiting the value of the exemption. When petition filed, debtor was over 70 years of age

and had an unlimited exemption (this case decided before In re (Dorothy) Davis (below) in

which SD Supreme Court ruled that provision unconstitutional.) When lien impairs homestead

exemption on the date the petition is filed, 522(f)(2)(A)requires the court to value the full value

of the homestead to determine if it is impaired. It was, and the lien was avoided.

EXEMPTIONS - CONVERSION OF ASSETS INTO EXEMPT PROPERTY

Andrawis, Ehab A 1998 #17

Debtor sold car to mother for fair market value and used proceeds to buy life insurance

policy. Fraud found in testimony debtor only intended to use life insurance purchase as a device

to shelter equity in the vehicle, in anticipation of the bankruptcy case, to a family member,

retaining free use of the asset. Had he intended to retain the policy or had another purpose in

19

purchasing it, the result might have been different. Though Hanson (848 F.2d 869) was

acknowledged, that family dealings alone are not extrinsic evidence of fraud, the court looked to

Kelly v. Armstrong (141 F.3d 799,802 (8th Cir. 1998) to find that here, family dealings were a

badge of fraud.

Powell, Susan M. 2006 #19

Conversion of cash into annuity (not in payment status) on eve of filing not fraudulent;

exemption allowed. S.D.C.L. 58-12-6 is limited only by 7, 8, and 9;not subject to S.D.C.L. 548A-4.

Torgerson, Ronald & Charlene 1995 #4

Objection to claimed annuity exemption overruled; Loan from relatives (properly secured

by perfecting interests in vehicle) alone, did not warrant finding extrinsic evidence of fraud.

Mere conversion insufficient.

EXEMPTIONS - DENIAL FOR BAD FAITH

Alderson, L.D. . . . . . . . . . 1991 #20

Debtor’s removal of assets to Nebraska led to finding he was absconding debtor under

S.D.C.L. 43-45-07, limiting his exemptions to absolute. Since Bankr. R. 1009 allows a debtor to

amend his schedules at any time before the case is closed, it is not within a court's discretion to

prohibit a debtor from making a timely amendment. In re Doan, 672 F.2d 831, 833 (11th Cir.

1982)(citing In re Gershenbaum, 598 F.2d 779, 781-82 (3rd Cir. 1979)). The Court of Appeals

for the Eleventh Circuit, however, recognized one caveat to that general rule. "[A] court might

deny leave to amend on a showing of a debtor's bad faith or of prejudice to creditors." Id. While

the court noted that simple delay in filing an amendment is not necessarily prejudicial to

creditors, it did find that concealment of an asset will bar exemption of that asset. Id.

20

A debtor's bad faith in filing an amended claim of exemption may be found if the debtor

knowingly makes a material, false statement in his schedules. Drewes v. Magnuson (In re

Magnuson), 113 B.R. 555, 558 (Bankr. D.N.D. 1989). "A statement is material if it concerns the

existence and disposition of property." Id. Failure to amend erroneous schedules promptly

constitutes reckless indifference to the truth, which is the equivalent of fraud. Id. at 559 (citations

omitted). Further, an exemption claim may be disallowed when a debtor fraudulently conceals an

asset that he later claims as exempt. Id. at 560 (citing In re Hanson, 41 B.R. 775, 778 (Bankr.

D.N.D. 1984)(2); Redmond v. Tuttle, 698 F.2d 414, 417 (10th Cir. 1983)); see also In re Roberts,

81 B.R. 354, 363 (Bankr. W.D. Pa. 1987). "Since fraudulent intent rarely is susceptible to direct

proof, courts long have accepted extrinsic evidence of fraud." Hanson v. First National Bank,

848 F.2d 866, 868 (8th Cir. 1988).

EXEMPTIONS - DETERMINATION OF APPLICABLE LAW

Alcorn, Zacchary McKensie & Jennifer Raechelle . . . . . . 2013 #3

In bankruptcy, debtor may choose between the exemptions listed in § 522(d) and those

provided in other federal law and in the law of the state in which the debtor was domiciled for

the 730-day period immediately preceding the date on which he filed his petition for relief or, if

the debtor was domiciled in more than one state during that 730-day period, the state in which

the debtor was domiciled for a longer portion of the 180-day period immediately preceding that

730-day period than in any other state. Here, Nebraska permitted a homestead and wages to be

claimed by non-residents of the state; its opt-out was limited to personal property. Further, its

opt out provision (like Arizona, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Florida) was limited to debtors filing

bankruptcy petitions within the state. As debtors filed in South Dakota, they were free to use

federal exemptions under 11 U.S.C. 522(2).

21

EXEMPTIONS - GENERAL

Alcorn, Zacchary McKensie & Jennifer Raechelle . . . . . . 2013 #3

See “Determination of Applicable Law” above.

Anderson, Gregory A. & Deanne M. . . . . 2002 #4

Where creditor sought permission to proceed with state court award of costs against the

estate and/or the debtors, relief from stay denied. When the offer of judgment was made, and

refused, the action was property of the estate, controlled by the trustee, not the debtors under

their claim of exemption.

Benedict, Leroy Dennis & Betty L. Fairbanks-Benedict . . . 2009 #2

Sanctions awarded against debtors’ counsel for indefensible attempts to claim property

exempt.

Fridrich, Harvey G. & Adeline L. 1995 #15

Account receivable (rent payment) owed to debtors on date of filing, scheduled and

claimed exempt, is property of the estate. When recovered by the trustee, debtors, under 11

U.S.C. 522(g), may amend exemption claim to maximize exemption under S.D.C.L. 43-45-4.

Ginsbach, Wesley & Julie . . . . 1991 #2

Property of the estate includes property in the hands of sheriff as a result of levy. Failure

to timely object to claim of exemption justified granting debtors motion for turnover (to the

trustee under 11 U.S.C. 542) subject to debtors’ allowed claim of exemption.

Larson, Lee Scott . . . . . . . . 1988 #24

A domicile "is that permanent fixed place of abode which [a] person intends to be his

residence and to which he intends to return despite temporary residences elsewhere or despite

temporary absences." State of domicile determines applicable exemptions. (Note case decided

22

pre-BAPCA.)

Ludwig, Nora Y. . . . . . . . . . 2001 #35

Debtor may amend exemption claim to maximize statutory allowance under S.D.C.L. 4345-4, where trustee’s post petition action increases the equity in the vehicles.

McLeod, Cara . . . . . . . . . . 1999 #21

Debtor scheduled and claimed exempt two preferential payments to mother and sister,

prior to filing. If debtor voluntarily transferred the property, she may not claim it exempt under

11 U.S.C. 522(g)(1)(A) if trustee recovers under § 547 or § 550. Further, if voluntary, Debtor

may not recover the preference under § 522(h), which is controlled by 522(g)(1).

Mefferd, Larry C. & Julie A. . . . . . . 2008 #7

While it may not always be possible to assign a precise value to an item of personal

property for the purposes of schedule B, a debtor must specify the dollar amount being claimed

exempt under S.D.C.L. § 43-45-4 on schedule C.

A claim of "all" or "unknown" is

inappropriate.

Ogle, Jessica Diane & Jeremy James (U.S. Dept. of Ag.v. Ogle) . . 2011 #2

Debtors' exemption claim in a tax refund is subject to the government's right of setoff,

and the government will be given relief from the automatic stay to effect the setoff.

Schomaker, Charles & Jeanette . . 1988 #22

Under Rule 1009, amendments to schedules (including claims of exemptions) may be

made at any time while the case remains open. Amendment must be served on all creditors and

parties in interest.

Swiontek, Roxanne R. . . . . . . . . . 2005 #45

The amount in debtor’s bank account on the date the petition is filed, and any tax refund

23

(pro-rated to date of filing), can only be claimed exempt under S.D.C.L. 43-45-4. Wages, earned

but unpaid on filing, cannot be claimed exempt under S.D.C.L. 43-45-4, per 21-18-53, and

S.D.C.L. 43-45-14.

The garnishment limitations do not serve as an additional exemption.

S.D.C.L.15-20-12 is not an exemption statute in addition to 43-45-4. This case is no longer valid

with respect to earned wages. See SL 2007 Ch 251 which amended S.D.C.L. 43-45-14 to permit

claiming earned wages exempt under S.D.C.L. 43-45-4 in bankruptcy, whether or not garnished.

Also see Kraft 07-3.

Tebay, Casey J. . . . . . . . . . 2000 #32

S.D.C.L. § 48-4-14 established that on the petition date, it was Debtor's interest in the

partnership itself that became bankruptcy estate property, not any interest specifically in the

sound system or other partnership property. This is because § 48-4-14 provides that "specific"

partnership property is not subject to attachment or execution for the debts against an individual

partner.

Tiede, Richard H. & Doris K. . . 1995 #29

Contract for deed payments not exempt because the property that is the subject of the

contract was never homestead property to begin with. (Note executory contract issue.)

Torigian, Joel L. & Diane J. . . 1996 #11

Potential income tax refund is property of the estate. See Kokoszka v. Belford, 417 U.S.

642, 648 (1974); Barowsky v. Serelson (In re Barowsky), 946 F.2d 1516, 1518 (10th Cir.

1991)(cites therein); Wetteroff v. Grand (In re Wetteroff), 453 F.2d 544, 546 (8th Cir. 1972); and

Riske v. Oliver (In re Oliver), 172 B.R. 924, 926 (Bankr. E.D. Mo. 1994). Compare Gehrig v.

Shreves (In re Gehrig), 491 F.2d 668 (8th Cir. 1974)(called into doubt by Kokoszka, 417 U.S. at

651, as discussed in Wallerstedt v. Sosne (In re Wallerstedt), 930 F.2d. 630, 632 (8th Cir. 1991)).

24

Further, the potential refund has value, even if the tax year is not complete when the petition is

filed. See Doan v. Hudgins (In re Doan), 672 F.2d 831, (11th Cir. 1982)(citing Segal v. Rochelle,

382 U.S. 375 (1966)); and United States v. Johnson (In re Johnson), 136 B.R. 306, 309 (Bankr.

M.D. Ga. 1991). In a Chapter 7 case, the value of the estate's interest in the refund generally is

prorated between the estate and debtors based on the date the case is filed. In re Orndoff, 100

B.R. 516, 517-18 (Bankr. E.D. Ca. 1989)(cites therein)

Van Dentop, Melvin D. . . . . . . 1997 #7

Balance in bank account on date case is filed is estate property. Attempt to increase

insurance exemption by paying off loan against life insurance policy, failed as check to life

insurance company had not been honored before the case was filed. If not presented or honored

by bank before the case is filed, the check does not result in funds being transferred. Trustee may

seek recovery of funds from transferee (life insurance company), under 11 U.S.C. 549(a). Date

of check’s honor is used when considering 549(a). Barnhill v. Johnson, 112 S.Ct. 1386 (1992)

Willman, Russell Eugene & Cindy Lou . . . . 2012 #2

Vacation time accrued before filing may be claimed exempt, as it is property of the

estate. If debtor has care custody or control of the property, and has not claimed it exempt, she

must deliver it to trustee under 11 U.S.C. 542. Otherwise, Trustee may pursue from debtor’s

employer, subject to discount under the restrictions of the employer-employee contract, such as

“use or lose” provisions and normal payroll tax and other withholding.

EXEMPTIONS - HEAD OF HOUSEHOLD

Bucaro, Patricia A. (bench ruling) . . . 2007 #4

Debtor, sole breadwinner for herself and daughter, is “Head of family”, not the adult

male living with debtor and her daughter, who earned more than debtor. Though he was member

25

of “household”, he was not member of “family”. S.D.C.L. 43-45-4

Dice, Roger L. . . . . . . . . . 1997 #12

Single person paying child support is entitled to “Head of family” status. S.D.C.L. 4345-4

Ferguson, Aisley B. . . . . . . 2006 #15

Debtor living with non-filing husband, making more income than debtor, is not a “head

of household” [sic] under 43-45-4.

Meier, Ryan Eugene & Rebecca Ann . . . . 2020 #8

Before filing bankruptcy, debtors had filed a divorce action in state court, and separated

with each debtor living with the children of their first marriage. Debtors argued each was the

head of his or her family, entitled to the “Head of Family” exemption under S.D.C.L. 43-45-4.

The court disagreed. “Family” is undefined in Chapter 43-45 and the court, relying on the plain

and ordinary meaning of “family” and “household” found in Black’s dictionary, and the

distinction between those two words found elsewhere in South Dakota’s code (S.D.C.L. 25-103(1) (protection orders) S.D.C.L. 57A-9-406(h) (uniform commercial code) and the Bucaro, and

Wilsey cases rejected debtors’ argument, holding that although separated, they were still legally

a family, and awarded the “Head of Family” exemption only to the wife, who had greater income

than the husband.

Olson, Jean D. . . . . . . . . . . 2005 #25

Widow living with adult son who was only sporadically employed and dependent upon

widow for support is “head of family” under S.D.C.L. 43-45-4. [In dicta, Court notes, that for

homestead purposes only, a “family” includes widow or widower, or any family member,

whether consisting of one or more persons in actual occupancy of the homestead. S.D.C.L. 43-

26

31-14.]

Schmidt, Marjorie Alvina . . . . 1997 #20

Debtor living with non-filing husband, found not to be “Head of Family” due to

information contained on Schedules I & J (income and expense statements) and also not a

“single” person (citing Holleman v. Gaynor, 237 N.W. 827 (S.D. 1931), therefore ineligible for

any personal property exemption, as S.D.C.L. 43-45-4 then read. [In 1998 [SL ch 265, 266], the

legislature amended “single person” to read “non-head of family”, to remedy this problem.]

Wilsey, Roger M. . . . . . . , 2007 #12

Debtor, living with adult female not related by blood or marriage, was not “head of

family” under S.D.C.L. 43-45-4.

EXEMPTIONS - HOMESTEAD

Aguirre, Antonio M. & Kelli D. (Aguirre v. Fullerton Lumber) 2007 #5

See Avoidance of liens, above.

Bohn, Dawn Marie (bench ruling) . . . . 2006 #4

Debtor may not claim her right to receive up to $10,000 exempt as proceeds under

S.D.C.L. 45-45-3, when her ex-husband sells her former homestead. Her right to payment is a

personal right under S.D.C.L. 2-14-2(19), and may only be claimed exempt under S.D.C.L. 4345-4.

Buxcel, Clifford & Elaine . . . . 1998 #12

In South Dakota, homestead must be “owned” by the debtor to be declared exempt, citing

US.v Nelson,969 F.2d 626, 631 (8th Cir. 1992). Though a debtor may possess a legal right to

buy back a homestead after foreclosure, that right does not constitute an ownership interest that

can be declared a homestead. Id. While Debtors were in discussion with SBA to repurchase their

27

home and ten acres and had tendered $15,000.00 to SBA for that purpose before their petition

date, a purchase agreement between Debtors and SBA was not signed by Debtors and the SBA

until late January, after Debtors had filed bankruptcy. Therefore, on the petition date, Debtors did

not have title to the real property, their redemption rights had expired, and they had no

enforceable purchase agreement with SBA. Debtors were in possession of the home but that

interest does not constitute an ownership interest that can be declared a homestead. See Nelson,

969 F.2d at 631. [NB: Other "Interests" may support claim of homestead under S.D.C.L.

43-31. See: In re Wood, 8 B.R. 882, SD Bkrtcy Ecker,1981)(e.g. home on land licensed from

Homestake Mining Company, sufficient.)

Gebur, Jerome Dean . . . . . . . 1999 #8

In October,1995 per state court divorce decree, non-debtor was ordered to pay debtor

“$11,000" to recognize his share in the equity of the marital home. To comply, she executed a

promissory note to pay over a ten year period with interest at 7%. Debtor conveyed his interest

by quit claim deed to non-debtor spouse, retaining a lien to satisfy the judgment. Debtors lien

was not the product of a voluntary sale, or a forced sale under S.D.C.L. 21-19. It was the

product of a divorce decree. Second, the proceeds of the sale were not used in the purchase of a

new homestead within one year of the date of sale (S.D.C.L. 43-45-3(2)). Consequently, the

homestead claim was denied.

Davis, Dorothy . . . . . . . . . 2003 #09

Because of the Judge Hoyt’s review of South Dakota homestead case law in this decision,

extensive excerpts are set out below. Debtor, who was 75 years of age when the petition was

filed, claimed her homestead valued at $95,000, exempt under S.D.C.L. 43-31-1,45-31-2, and

45-45-3. S.D.C.L. 43-31-1, provided in part that the homestead held by a person age 70 or over

28

is exempt from sale for taxes as long as it continues "to possess the character of a homestead."

S.D.C.L. § 43-31-2, sets forth inter alia the general qualification that the homestead "must

embrace the house used as a home by the owner." S.D.C.L. § 43-45-3, provides that if a

homestead is sold voluntarily or under Chapter 21-19 of the state code, then proceeds of the sale

to the extent of $30,000 are exempt. Section 43-45-3 also contains an exception to the $30,000

limit on which Debtor relied. The exception in S.D.C.L. § 43-45-3(2) provides, "Such exemption

shall not be limited to thirty thousand dollars for a homestead of a person seventy years of age or

older or the unremarried surviving spouse of such person so long as it continues to possess the

character of a homestead."

In his brief, Trustee Lovald first argued that 11 U.S.C. § 544

imposes a lien on Debtor's equity in her home and that this lien can be realized when the house is

no longer used as her home. Trustee Lovald's second argument was that, if Debtor could have an

unlimited homestead under S.D.C.L. § 43-45-3, then that state statute violates Article VI, § 18,

and Article XXI, § 4, of the South Dakota Constitution.

In her brief, Debtor argued that her homestead exemption must be fixed on the petition

date and not contingent on a possible future event. She cited several cases, relying most on

Armstrong v. Peterson (In re Peterson), 897 F.2d 935, 937-38 (8th Cir. 1990). Debtor also

responded to Trustee Lovald's two arguments that § 43-45-3's provision for persons age 70 and

over is unconstitutional. Finally, Debtor argued that as a matter of public policy Debtor's

homestead exemption should be upheld and not subject to later divestiture.

In In re Ned Maryott, Bankr. No. 01-10052, slip op. (Bankr. D.S.D. Sept. 24, 2001), the

Court delved briefly into the history of subsection (2) of § 43-45-3.

Except for the last sentence of subsection (2), § 43-45-3 has been a part of South Dakota's

homestead laws since at least 1939 with only the value limitation changing over the years. See

29

S.D.C. § 51.1802(7)(1939). The last sentence in subsection (2) was added in 1980. S.L. 1980, ch.

296, § 3. The phrase "so long as it continues to possess the character of a homestead," which is a

part of the last sentence in subsection (2), has been a part of § 43-31-1 and that statute's earlier

versions since at least 1874-75. See S.L. 1874-75, ch. 37, § 1 (Dak. Terr.). Maryott, slip op. at

12 n.6. In Maryott, the Court also expressed concern about some of the conclusions reached in

Beck v. Lapsley, 593 N.W.2d 410 (S.D. 1999), where the court limited the 70 or older person's

exemption to only $30,000 in proceeds if the homestead is voluntarily sold.

In Beck, the South Dakota Supreme Court, with limited discussion, concluded that upon a

voluntary sale of a homestead, the property no longer possesses the character of a homestead, as

required by § 43-45-3(2). Beck, 593 N.W.2d at 413. The state Supreme Court thus has interpreted

§ 43-45-3(2) to provide that a debtor, age 70 or over, may protect a homestead of any value from

an execution sale, but that he may protect only $30,000 in proceeds for one year if he voluntarily

sells his home. Id. at 412-13.

The conclusion in Beck appears to be inconsistent with S.D.C.L. § 43-31-9, which states

an owner may change his homestead entirely, and S.D.C.L. § 43-31-11, which provides that

"[t]he new homestead shall in all cases be exempt to the same extent and in the same manner as

the old or former homestead was exempt."7 [Footnote 7.: The provisions of S.D.C.L. §§ 43-31-9

and 43-31-11 have been a part of South Dakota's homestead laws since 1875. See S.L. 1874-75,

ch. 37, §§ 12 and 13 (Dak. Terr.).] The conclusion in Beck also appears to be inconsistent with

earlier case law. See Christiansen v. United National Bank of Vermillion, 176 N.W.2d 65, 67

(S.D. 1970)(upon a voluntary sale, every protection originally given to the homestead right

adheres to the proceeds for one year after receipt);Smith v. Midland National Life Insurance Co.,

234 N.W. 20, 21 (S.D. 1930)("An attempt to sell the property is not in and of itself any evidence

30

of an abandonment." Smith v. Hart, 207 N.W. 657, 658-59 (S.D. 1926)(in order to give full effect

to the state's statute that allows an owner to change his homestead, the proceeds from a voluntary

sale of a homestead, which the owner intends to reinvest in a new homestead, must be protected

from creditors)8 [Footnote 8: As discussed in Christiansen, 176 N.W.2d at 67, Smith v. Hart

prompted a change in South Dakota's homestead exemption statutes to clarify that a voluntary

sale did not constitute an abandonment of the homestead.]; see also Keleher v. Technicolor

Government Services, Inc., 829 F.2d 691, 693 (8th Cir. 1987)(a debtor cannot be presumed to

willingly imperil his homestead or homestead proceeds unless necessity so requires or he

expressly does so)(cites therein); Botsford Lumber Co. v. Clouse (In re Clouse's Estate), 257

N.W. 106, 108 (S.D. 1934)(the homestead privilege ceases when there is no longer any reason for

the homestead). Maryott, slip op. at 13-14. This Court then went on to discuss its holding in In

re Hughes, 244 B.R. 805 (Bankr. D.S.D. 1999), and to reach a conclusion on the multifaceted

homestead issue presented in Maryott.

In Hughes, this Court applied S.D.C.L. § 43-45-3(2) in a case where the debtor was under

age 70. The Court concluded that equity in a homestead in excess of $30,000 was property of the

bankruptcy estate available to pay creditor's claims. Hughes, 244 B.R. at 810-12. The Court

noted in Hughes that the same conclusion would be reached regardless of whether the debtor's

bankruptcy petition was deemed a voluntary sale of the property, see Karcher v. Gans, 83 N.W.

431, 432 (S.D. 1900)(cited inHughes, 244 B.R. at 813 and 813 n.6), or whether the case trustee

accessed the equity by standing in the shoes of a judgment lien creditor. Hughes, 244 B.R. at

812-13.

In light of the South Dakota Supreme Court's recent ruling in Beck, it appears that a

different result would be reached in this case, where Debtor is age 70 or older, depending on

31

which theory was applied. If we considered Debtor's bankruptcy petition as putting the trustee in

the shoes of a judgment lien creditor, Debtor's entire homestead would be protected, regardless

of value, because the Trustee could not force an execution sale. However, if we considered

Debtor's bankruptcy as a voluntary transfer of his property, including his homestead, then under

Beck Debtor could only protect $30,000 in equity. The Court will not force that loss of

exemption upon Debtor by deeming his Chapter 7 petition to be a voluntary transfer of his and

his wife's homestead property. First, to do so would be inconsistent with S.D.C.L. §§ 43-31-9

and 11, which allow a debtor to change his homestead without peril to his exemption. Second,

exemption laws are to be construed liberally in the debtor's favor. Wallerstedt v. Sosne (In re

Wallerstedt), 930 F.2d 630, 631 (8th Cir. 1991)(cited in Andersen v. Ries (In re Andersen), 259

B.R. 687, 690 (B.A.P. 8th Cir. 2001)). Third, the application of exemption laws should not be

altered by the filing of a bankruptcy petition. See Hughes, 244 B.R. at 812. Finally, this result is

consistent with the Court's decision on a related judgment discharge issue in Langford State

Bank v. West (In re West), Bankr. No. 99-10322, Adv. No. 00-1013, slip op. at 3-4 (Bankr. D.S.D.

Dec. 26, 2000). Accordingly, Debtor may declare the entire 160 acres exempt as his homestead,

regardless of value. Trustee Pfeiffer, as a hypothetical judgment lien creditor, or other actual

judgment lien creditors may not access any equity in this homestead that may exceed $30,000.

Maryott, slip op. at 14-16.

The twist that Trustee Lovald has added in this case, that distinguishes it from Maryott, is

his specific request that Debtor's case be held open so that he can recoup the equity in Debtor's

home should the home loose its homestead character sometime in the future. This argument does

not survive scrutiny.

A debtor's entitlement to an exemption is determined on the day he files his bankruptcy

32

petition. 11 U.S.C. § 522(b)(2)(A);Peterson, 897 F.2d at 937-39; and Mueller v. Buckley (In re

Mueller), 215 B.R. 1018, 1022 (8th Cir. B.A.P. 1998)(cites therein). Further, as noted earlier,

exemptions are construed liberally in favor of the debtor. Wallerstedt v. Sosne (In re

Wallerstedt), 930 F.2d 630, 631 (8th Cir. 1991). In light of these basic tenets and this Court's

earlier holding in Maryott, the Court concludes that Trustee Lovald may not hold open Debtor's

case until her home is no longer her homestead and then recover, on some future date, her equity

in it.

The court then referred the constitutional argument to the District Court to request an

opinion of the State Supreme Court. The Supreme Court agreed with the trustee that Article

XXI, §4 requires a dollar limit (area limit insufficient) on the exemption. See below.

In In re Davis, 2004 SD 770, 681 N.W.2 452 (S.D., 2004)

The United States District Court for the District of South Dakota, the Honorable

Lawrence L. Piersol, Chief Judge, certified two questions for this Court: (1) Whether the last

sentence of S.D.C.L. 43-45-3(2) violates Article VI §18 of the South Dakota Constitution. (2)

Whether the last sentence of S.D.C.L. 43-45-3(2) violates Article XXI §4 of the South Dakota

Constitution. On the first question, we rule in the negative, but on the second question, we hold

that because the last sentence of S.D.C.L. 43-45-3(2) fails to set a limit on the amount of a

homestead exemption that may be claimed by persons seventy or older, it violates Article XXI

§4 of our Constitution. Note: in response to this case, in 2005 (SL 2005, Ch 235, §1) the

legislature established a monetary limit of $170,000.00 for a person 70 years of age or older, or

the un-remarried surviving spouse of such person.

Dice, Roger L. . . . . . . . . . 1997 #12

Land may not be claimed exempt under 43-45-4, which is limited to personal property.

33

Intention to occupy homestead must be evidenced by actual occupancy within a reasonable time.

Feucht, Teresa J. . . . . . . . . 2006 #16

Though Debtor testified there were certain circumstances under which she would return

to the Fairview house, none of those circumstances existed on the petition date, and none

appeared on the horizon. Further, Debtor’s removal from the Fairview house was not due to

temporary circumstances related to her employment or health. Compare In re Johnson, 61 B.R.

858 (Bankr. D.S.D. 1986)(the debtor did not lose her homestead interest when she moved into a

nursing home); Smith v. Midland National Life Ins. Co., 234 N.W. 20 (S.D. 1930) (temporary

absence from homestead for employment due to financial difficulties does not constitute an

intent to abandon the homestead). Instead, ”[a]ctual removal without intention to return is a

forfeiture of the homestead right. If one removes from homestead property without any present

intention of returning, but with a mere possible, or at most probable future purpose to do so,

contingent upon the happening or not happening of a particular event, the homestead is

abandoned.” Yellowhair v. Pratt, 182 N.W. 702, 703 (S.D. 1921). Those are the circumstances

presented here. Debtor abandoned her homestead interest in the Fairview house and on the

petition date had no present, non contingent intention to return. Accordingly, Debtor abandoned

her homestead interest in the Fairview house, and she may not claim a homestead exemption in

it.

Fredricks, Evert L. & Rhoda A. . . . . 2000 #35

No abandonment of homestead where debtor intends to move back to homestead when

she retires, and no evidence to the contrary. Work in a nearby town and financial problems

contributed to absence from the house.

Hanson, Steven D. & Bonnie M. . . . . 2001 #19

34

Citing Gebur above, objection to claim of proceeds from disposition of marital property,

was sustained. Once debtor permanently removed himself from the family home, it was no

longer his homestead, although he still had an ownership interest. S.D.C.L. § 25-4-33 (there is no

presumption of common domicile after separation; United States v. Nelson, 969 F.2d 626, 631

(8th Cir. 1992)("Homestead rights under South Dakota law accrue only to owners who use the

property as a home...."). That fact was seemingly recognized by the language in the quit claim

deed he gave his former spouse. Debtor also may have abandoned his homestead interest in the

former marital home when he established a new homestead. See Warner v. Hopkins, 176 N.W. at

748. However, since there was no evidence of when he left the marital home without a present

intent to return or when he established his new homestead, the Court does not rely on either his

departure or the creation of a new homestead as the cutoff point for his homestead interest in his

former marital home.

Herding, Jamie L. . . . . . . . . . . 2007 #4

Debtor left marital home pursuant to a protection order. Though he claimed a homestead

interest in the former marital home, he stopped making the mortgage payments and in his

statement of intention, said he intended to abandon the home to the mortgagee. He argued he

intended to preserve his share of the homestead equity, notwithstanding the statement of

intention. The court found that in negotiating property settlement offers in the divorce action,

debtor had abandoned claims in the homestead in an attempt to keep land he owned in North

Dakota. Debtor had abandoned his interest in the marital home, by failing to take any action to

lawfully return to and to use the marital house as his home.

Hoffman Farms . . . . . . . . . . 1994 #16

Section 21-19-29 of the South Dakota Code provides that an order directing the sale of a

35

homestead shall provide: unless waived by the debtor that sale of the homestead be not had for

sixty days, and that at any time prior to the sale the debtor may, at his option, pay to the officer

the surplus of the determined valuation of said homestead over and above such homestead

exemption plus all encumbrances.

Contrary to Debtors' assertion, this provision does not give Debtors the right to purchase

the homestead parcel after the sale. It is a right to be exercised before the sale. Debtors did not do

so. Debtors did not raise any objections to the sale based on potential rights under S.D.C.L. §

21-19-29 in their October 12, 1994 objection to the Trustee's Notice of Proposed Action for Sale

of Real Estate by Auction Sale Free and Clear of Liens. Consequently, the Court concludes that

Debtors may not rely on S.D.C.L. § 21-19-29 now in an attempt to purchase the homestead

property from the Trustee at the sale price, less their homestead claim.(8)

Finally, Debtors may claim a homestead exemption only to the extent that equity up to

$30,000.00 exists over and above encumbrances. Peck v. Peck, 212 N.W. 872 (S.D. 1927); First

National Bank of Beresford v. Anderson, 332 N.W.2d 723, 726 (S.D. 1983). After application of

FmHA's mortgage, no equity exists on which Debtors may claim a homestead exemption and

Debtors have no rights under S.D.C.L. § 21-19-29 that they may exercise.

Hughes, Jessie Joyce & Carroll Lee .. 1999 #25

Debtors' constitutional arguments are essentially that the Trustee cannot use § 21-19-2 to

force a sale of the homestead because it would be a pre-judgment taking and that § 21-19-2

impermissibly allows the forced sale of a homestead while not allowing the sale of other

absolutely exempt property. Debtors' arguments are premised on the conclusions that a

homestead in South Dakota is always absolutely exempt and is not subject to a judicial lien or

sale.

36

As discussed below, the Trustee's authority to sell the property is not an exclusive

product of S.D.C.L. § 21-19-2. However, to the extent that Trustee Lovald may need to rely on §

21-19-2 to obtain court approval to sell the homestead under either 11 U.S.C. § 363(f)(1) or (5),

each of which could incorporate S.D.C.L. § 21-19-2, the Court will consider Debtors'

constitutional challenges to § 21-19-2.

Debtors' constitutional challenge of S.D.C.L. § 21-19-2 fails to consider the statute in the

whole context of chapter 21-19. Debtors' arguments surrounding the constitutionality of S.D.C.L.

§ 21-19-2 isolates the statute from other sections of ch. 21-19 and yields distorted conclusions.

Section § 21-19-2 is just an initial step in the process a judgment creditor must follow to obtain a

sale of a homestead to recover on a debt. All provisions of ch. 21-19 must be considered part of

the homestead sale process. Linquist v. Bowen, 813 F.2d 884, 888-89 (8th Cir. 1987); Nielson v.

AT&T Corp., 597 N.W.2d 434, 439 (S.D. 1999). For example, § 21-19-24 provides for a

valuation hearing and § 21-19-29 requires an execution before the sale is conducted.

Article XXI, § 4 of the South Dakota Constitution directs the legislature to limit the value

and define by law that homestead which shall be exempt from forced sale.(1) Section 43-31-1 of

the state code, which creates the homestead exemption, recognizes that directive by providing

that the homestead exemption exists "to the extent and as provided in this code[.]" Section

43-45-3(2) then sets forth the value limitation., when the homestead is voluntarily sold or is sold

pursuant to S.D.C.L. ch. 21-19.

The homestead is a privilege granted by law, not an estate in land. In re Wood, 8 B.R.

882, 887 (Bankr. D.S.D. 1981)(citing Botsford Lumber Co. v. Clouse, 257 N.W. 106, 108 (S.D.

1934)(cited in Schutterle v. Schutterle, 260 N.W.2d 341 (S.D. 1977))); Speck, 318 N.W.2d at 344

37

(quoting Clouse, 257 N.W. at 108). A defined homestead has significance in areas of law other

than debtor-creditor matters, see, e.g., S.D.C.L. § 25-2-7 and § 29A-2-402, and is distinct from

the homestead exemption. See S.D.C.L. § 21-19-2 (both terms used), and Hansen, 166 N.W. at

428. Compare S.D.C.L. §§ 43-31-1 and 43-45-3 (homestead exemption statutes) to S.D.C.L. §§

43-31-2, -3, and -4 (homestead definition statutes).

The value limitation on a homestead exemption has significance only when the

homestead is the subject of litigation between the homestead owner and a judgment creditor.

O'Neill v. Bennett, 207 N.W. 543, 546 (S.D. 1926); see also Rohl v. McCullough (In re Rohl), 34

F.2d 268, 270 (8th Cir. 1929)(under the Bankruptcy Act, the case trustee could avoid

pre-petition homestead sale by the debtor; the debtor's wife was entitled to $5,000 in homestead

sale proceeds as her homestead exemption). Once the value of a homestead exceeds the protected

exemption amount, a creditor may seek recovery of the excess to pay his claim. S.D.C.L. ch.

21-19. As explained in an early decision entered shortly after a value limitation was first

adopted,

[t]he result is that, where the owner of a homestead is free from debts, his homestead,

may consist of 160 acres of land, with improvements thereon, free from all limitation as to value.