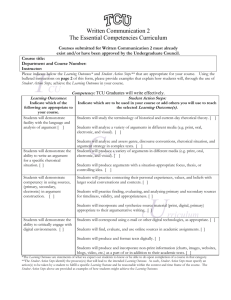

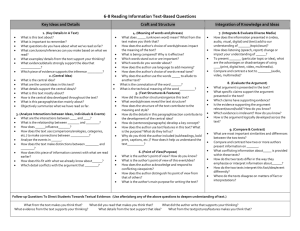

Key Activities Repeated Over the Semester - Wiki

advertisement