English Notes January 13, 2016 The Things They Carried

advertisement

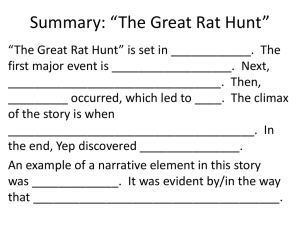

English Notes January 13, 2016 The Things They Carried Homework: Read “How to Tell a True War Story” for Thursday Review of Chapter Questions “On the Rainy River” 1. The narrator never told this story before because it was too hard to talk about. Bravery would be following his conscience and not going to war. However, he feels he is a coward by going to war. There is courage in telling the story. 2. Yes, young people still have difficulty connecting to world events. However, now people are more connected to world events through the Internet (consider Paris attacks, etc.). 3. Detailed description of narrator’s job—narrator is dealing with the slaughter of pigs. There is death all around him at his job. There is blood, killing, awful smells, smell on his hands he can’t seem to get rid ofparallels the guilt/memories he can’t “wash” away from the war (we know he killed a man in war), parallels the use of a gun (pressure gun for pigs, gun as a weapon in war). Weight of stink at the slaughterhouse could parallel the weight of the war when it is over. 4. Conflict—gong to war or not. Go to Canada or go to Vietnam. 5. Climax of the story—on the boat, narrator can see Canada, has a vision where he sees his past, present and future (moment of transcendence where he can see all time, all actions, all consequences). Narrator feels he is a coward for going to war—he doesn’t want to feel the shame of his family. All the voices in his head are trying to gain his attention to sway his decision. 6. Elroy Berdhal: older man, wise owns a motel/cabin where narrator sleeps caring, concerned about the narrator doesn’t ask questions, gives space, remains neutral, gives narrator security to come to his own decision about going to war seemed to know why Tim was there can communicate with Tim without saying anythingby not saying anything, this helps Tim figure out his problems on his own sympathetic, supportive *doesn’t judge*--this is key for Tim to come to his own decision leaves Tim the emergency fund—if Tim wants to go to Canada he can, he has options 7. “I was a coward. I went to war.” The narrator/Tim basically gave in to peer pressure. He didn’t follow his heart, but instead, followed the expectations of others. He goes to war because he is a coward—he can’t stand up to the majority opinion about the war. Tim remains haunted—he killed a man, he has the weight of the war on him—he has to continually deal with the consequences of the aftermath of war. Review of “Enemies” Jensen was bigger and stronger and kept hitting Strunk on the nose. Jensen kept hitting him over and over with “quick stiff punches that did not miss” and it took three guys to pull him off. Jensen lost control and one afternoon began firing his weapon into the air, yelling Strunk’s name, and it didn’t stop until he’d rattled off an entire magazine of ammunition. He then used the barrel of his gun to break his own nose. The two pledge to each other that they will make a pact that if one is injured badly/crippled that the other will help end his life. Purpose of chapters—to describe trust between soldiers Graphic depiction of Strunk’s leg being severed—shows the reality of war, how difficult it is/was to get through war without getting injured “Friends” Jensen and Strunk didn’t become instant buddies, but made a pact that the other guy would automatically find a way to end the other’s life if they ever got mangled in the war Strunk stepped on a rigged mortar round and it took of his right leg at the knee Strunk was worried Jensen would kill him (remember the pact) Strunk thinks his leg can be sewn on—he fears Jensen will kill him and makes him promise/swear he won’t kill him Strunk died in the helicopter which “seemed to relieve Dave Jensen of an enormous weight” (63). Jensen was relieved of the responsibility of killing Strunk. He no longer has to wonder if he should have killed him or not. *****These notes will help you with the reading! ***** “How to Tell a True War Story” Main Characters: Curt Lemon—killed/blown up Rat Kiley—friend of Curt, very angry/upset over losing his friend, shoots a baby water buffalo Mitchell Sanders—has a yo-yo, tells a story about men hearing voices on listening patrol Bob Kiley—called “Rat” Has a friend that gets killed, so he writes the sister of the killed soldier a letter He says in his letter how this soldier would volunteer for things no one else would and that he was very brave. Rat also says that he was a “great, great guy.” Rat gets teary writing the letter. Rat says the soldier knew how to have a good time and that he threw a grenade into a river to blow up fish. This soldier also went trick or treating almost stark naked and was “nuts” Rat also admits that he “loved the guy” and that they were “soul mates” or “like twins” and hopes that the sister writes back. He tells the man’s sister he’ll look her up when the war’s over. After 2 months, the sister never writes back. We can infer she was disturbed by the letter. ___________________________________________________________________________ Narrator—says true war stories are not moral—know that it’s obscene and evil. Rat’s story is true because he uses obscenity. Dead guy = Curt Lemon Lemon and Kiley were goofing around and went on a “nature hike” and used smoke grenades to play catch. It was a game of chickenremember, they are 19. Lemon was then blown up (maybe he stepped on a mine). “A true war story cannot be believed. If you believe it, be skeptical. It’s a question of credibility. Often the crazy stuff is true and the normal stuff isn’t, because the normal stuff is necessary to make you believe the truly incredible craziness” (68). _____________________________________________________________________________________ Mitchell Sanders tells a story about a 6 man patrol that goes up to the mountains to just listening. They can’t talk for 7 straight days. On listening duty the men hear Vietnamese music –they can’t report music and they can’t talk (remember how spooky the setting is—very dark, misty) One night the men believe they overhear a cocktail party, voices, martini glasses, chamber music, then Vietnamese music, chanting Then they think the rock is talk, fog is talking, grass—everything. They are starting to lose it. The guys can’t cope and start shooting and using napalm—they begin burning everything on the mountain. (Even though they blow everything up, they still can’t stop hearing the sounds.) Even though all is quiet, and there is only fog, they “hear it” When the soldiers report back they don’t say anything. “The whole war is right there in that stare. It says everything you can’t ever say. It says, man, you got wax in your ears…Then they salute the f----r and walk away, because certain stories you don’t ever tell” (72). Sanders wanted the narrator to believe his story. Sanders says the moral of his story is “Nobody listens. Nobody hears nothin’. Like that f----colonel. The politicians, all the civilian types…” (73). “What they need is to go out on LP. The vapors, man. Trees and rocks—you got to listen to your enemy” (72). Sanders admits that parts of his story aren’t true (glee club, opera—exaggeration). “That quiet—just listen. There’s your moral” (74). Narrator says “Then he [Sanders] shrugged and gave me a stare that lasted all day” (74). Narrator/Tim also exaggerates. It’s hard to tell a war story without exaggeration. “A true war story, if truly told, makes the stomach believe” (74). Soldiers crossed the river. Rat shot a baby water buffalo. He shoots parts of the buffalo (legs, nose, etc.)—not to kill it, but to make it hurt. Rat’s friend Curt died—he is taking out his anger on this baby water buffalo. Mitchell Sanders says, “Well, that’s Nam, Garden of Evil. Over here, man, every sin’s real fresh and original” (76). The water buffalo was still alive even though it was badly hurt. It was dumped in a village well. Narrator says—“War is nasty; war is fun. War is thrilling; war is drudgery. War makes you a man; war makes you dead. The truths are contradictory. It can be argued, for instance, that war is grotesque. But in truth war is also beauty. For all its horror, you can’t help but gape at the awful majesty of combat” (76-77). “…and a true war story will tell the truth about this, though the truth is ugly” (77). “In war you lose your sense of the definite, hence your sense of truth itself, and therefore it’s safe to say that in a true war story nothing is ever absolutely true” (78). Pieces of Curt Lemon were blown everywhere and were hanging off a tree. “The gore was horrible, and stays with me. But what wakes me up twenty years later is Dave Jensen singing “Lemon Tree” as we threw down the parts” (79). War stories: “ A thing may happen and be a total lie; another thing may not happen and be truer than the truth” (80). “You can tell a true war story if you just keep on telling it” (81). “And in the end, of course, a true war story is never about war” (81). It may not be true to the facts, but it’s true to the feeling. What matters more in a true war story is how you feel after hearing it. “The Dentist” Didn’t know Curt Lemon well—he seemed to always play the tough soldier role, had a high opinion of himself (or was he just insecure, and acting tough?) Dentist visits soldiers. Curt Lemon was anxious, fidgeting, claims he had a bad dental experience. Lemon fainted before the dentist touched him. After fainting, he wouldn’t talk to anyone and sat alone under a tree (embarrassed). Lemon told the dentist he had a toothache and urged the dentist to yank out a perfectly good tooth. Lemon overcame his fear, and saved his reputation “Sweetheart of the Song of Tra Bong” Tim tells Rat’s storyRat’s story is about Mark Fossie and his girlfriend Rat—reputation for exaggeration and overstatement of his stories. Most men in the troop knew this. Rat wanted to “heat up the truth, to make it burn so hot that you would feel exactly what he felt.” This story, however, Rat never backed down from Rat said “I saw it, man. I was right there. This guy did it.” Rat’s answer to Sanders We find out that Rat’s story is regarding a soldier who got his blonde girlfriend to come to war In the village of Tra Bong the men didn’t have to keep the same standards—could grow their hair, didn’t have to polish their boots, could drink cold beer Green Berets—loners by nature, “Greenies” who avoided associating with the others Rat said he felt safe there—seemed like the war was far away and things were peaceful. Men played volleyball, lazed away the afternoons, drank Eddie Diamond—came up with the idea to have Vietnamese women come to sleep with the soldiers there. Another solider, Mark Fossie, brought the subject up again. Mark Fossie’s 17 year old girlfriend showed up (Mary Anne) 6 weeks after the conversation Fossie said it was expensive and complicated, but he was able to fly Mary Anne to Vietnam. He says he was able to do this because he wanted it enough. Fossie and Mary Anne Bell were high school sweethearts who were in love. They planned on marrying one day. Mary Anne—“good for morale” and fun to have around. Fossie was very much in love for her. Mary Anne learned Vietnamese, cooked rice, learned about the base, trip flares, etc. She wanted to learn more about the land and who lived there. She seemed “at home” there and loved to see the simplicity of village life. Eddie knew she would learn about war measures. Rat reenters the narration. He tells the men that by the end of the second week Mary Anne wasn’t afraid to get her hands bloody. She took care of 4 casualties. She learned how to tend to bloody victims—clipped arteries, made splints. She amazed Mark Fossie. Mary Anne stopped wearing jewelry, cut her hair short, didn’t wear make-up, learned how to disassemble a gun (M 16)—she became confident and changed into a soldier. Mary Anne didn’t want to go home. Her relationship with Mark changed—she now expressed her thoughts. She questioned the amount of kids she wanted, living together before marriage, etc. She didn’t seem bubbly, nervous or giggly. At night she looked into the dark in silence. She said she was never happier in her whole life. One morning Fossie told Rat that he couldn’t find Mary Anne—she was gone. Fossie claimed Mary Anne was sleeping with an 18 year old (Eddie Diamond?—we find out it wasn’t him). Rat and Fossie search for Mary Anne. She wasn’t with the other soldiers in their troop. They search the mess hall, helipad, etc. Rat, when telling the story looks at Sanders for “his vote” as to what happened to her. Sanders thinks she snuck off with the Green Berets. Mary Anne came back. She wore a bush hat and fatigues. She told Fossie they would talk later. He wanted to know NOW what happened. Fossie set down “rules” and Mary Anne went back to being shampooed, wearing nice clothing, being polite. She looked to Fossie for clearance when others asked her about the Green Beret ambush. Fossie reveals that he and Mary Anne are engaged. They “compromised” on things. Mary Anne and Fossie sunbathed together, seemed perfect—however it “seemed” like they were prefect but they weren’t If Mary Anne left Fossie’s side he would tense up. Mary Anne and Fossie were “too intense”—held hands, talked of their wedding Fossie made arrangements to send Mary Anne home. Mary Anne became gloomy and “seemed to disappear inside herself”---“The wilderness seemed to draw her in” and it was “as if she had come up on the edge of something, as if she were caught in that no-man’s land between the Cleveland Heights and deep jungle” (100). Rat sees silhouettes in the distance. He said he saw Mary Anne’s eyes (now jungle green, not blue). Mary Anne had a weapon and was with Special Forces. When Rat usually tells a story he goes off topic to clarify things. Sanders would redirect Rat back to telling the story. Sanders believed digressions changed the flow of the story. Rat said that she “joined the zoo”—end of story Fossie waited for Mary Anne all day. Rat cautions Fossie that he shouldn’t mess with “Greenie types” After midnight Rat and Eddie went to check on Fossie. He was swaying to music—he thought he heard Mary Anne. The men enter a room—decaying animals, stench. Rat said he couldn’t process it all. The background music came from a tape deck—the high voice was Mary Anne’s.