focus of the chapter

advertisement

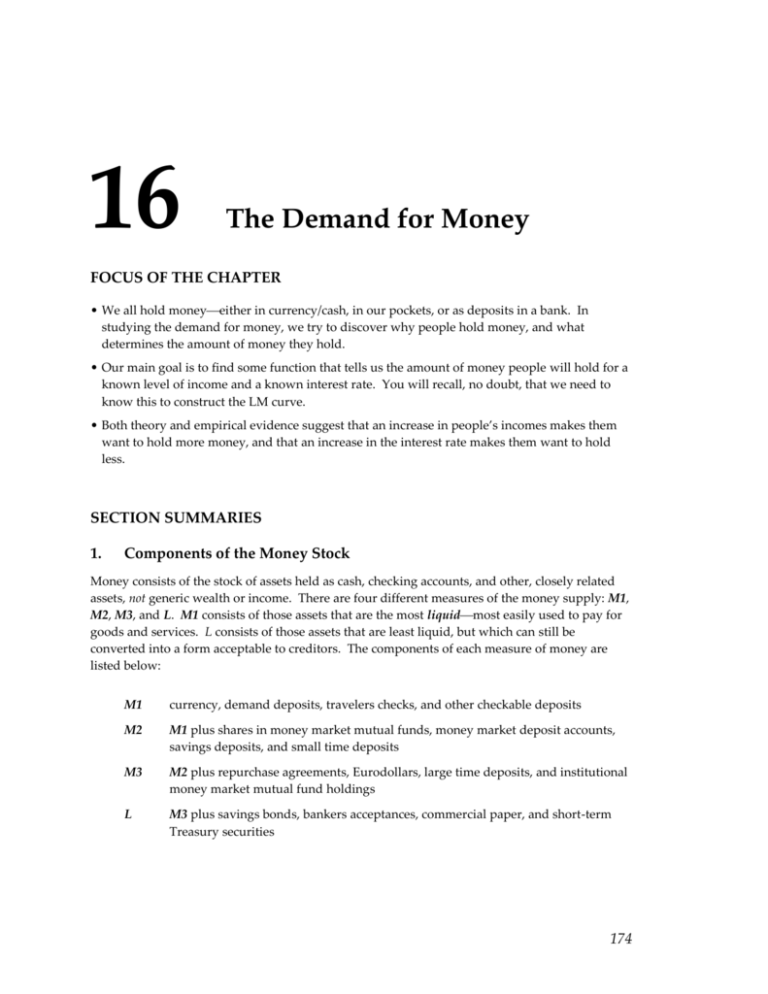

16 The Demand for Money FOCUS OF THE CHAPTER • We all hold moneyeither in currency/cash, in our pockets, or as deposits in a bank. In studying the demand for money, we try to discover why people hold money, and what determines the amount of money they hold. • Our main goal is to find some function that tells us the amount of money people will hold for a known level of income and a known interest rate. You will recall, no doubt, that we need to know this to construct the LM curve. • Both theory and empirical evidence suggest that an increase in people’s incomes makes them want to hold more money, and that an increase in the interest rate makes them want to hold less. SECTION SUMMARIES 1. Components of the Money Stock Money consists of the stock of assets held as cash, checking accounts, and other, closely related assets, not generic wealth or income. There are four different measures of the money supply: M1, M2, M3, and L. M1 consists of those assets that are the most liquidmost easily used to pay for goods and services. L consists of those assets that are least liquid, but which can still be converted into a form acceptable to creditors. The components of each measure of money are listed below: M1 currency, demand deposits, travelers checks, and other checkable deposits M2 M1 plus shares in money market mutual funds, money market deposit accounts, savings deposits, and small time deposits M3 M2 plus repurchase agreements, Eurodollars, large time deposits, and institutional money market mutual fund holdings L M3 plus savings bonds, bankers acceptances, commercial paper, and short-term Treasury securities 174 THE DEMAND FOR MONEY 2. 175 The Functions of Money Money has traditionally been thought to have four functions: A medium of exchange. Money is used to pay for goods and services, and enables us to avoid the “double coincidence of wants” required in a barter economy. A store of value. Money retains its value over time; money we receive today can be stuck under our mattresses or placed in our checking account and used to purchase goods and services at a later date. A unit of account. Prices are quoted in dollars and cents rather than chickens, avocados, or visits to the dentist. A standard of deferred payment. Money is used in long-term transactions; you might borrow $100 from a friend, for example, and promise to pay him back $105 at a later date. The most important thing to know about money is that it is whatever people generally accept as a payment for goods and services. As such, it can take many forms. 3. The Demand for Money: Theory Why would we ever choose to hold money instead of some other, interest-bearing asset? Keynes suggested three different motives: The transactions motive. We wish to avoid having to cash in another asset every time we make a purchase. (Imagine what a nuisance that would be!) The precautionary motive. “Just in case.” We never know our spending plans exactly; it pays to keep a little extra money around in case the urge for a hot fudge sundae hits at a time when your stockbroker is playing golf and cannot liquidate any of your assets. The speculative motive. While money doesn’t have a very high return, it is less risky than other assets. Speculative demand for money is actually demand for a safe asset. An increase in the rate of return on other assets reduces the demand for money, whatever one’s motive for holding it. An increase in the amount of uncertainty we have about our future spending plans increases the people’s demand for money, when that demand is based on the precautionary motive. We model the demand for real rather than nominal money balances here ( M P rather than M); we assume that, because people hold money for its purchasing power, they do not care about their nominal money holdings. For this to hold, people must be free of money illusionthe belief that changes in nominal wages and prices are meaningful. 176 CHAPTER 16 4. Empirical Evidence Empirical research has settled four key points about money demand: 1) When the real interest rate increases, the demand for real money balances falls. 2) When income increases, money demand also increases. 3) It takes time for money demand to fully adjust to changes in income and the interest rate. 4) If the price level doubles, so will nominal money demand. Real money demand will be unaffected; there is no money illusion. High inflation can also induce people to hold less money. With sufficiently high rates of inflation, people may not wish to hold financial assets at all, holding food, other goods (especially gold) and foreign money instead. This phenomenon is known as flight out of (domestic) money. 5. The Income Velocity of Money The income velocity of money is the number of times the stock of money is turned over, or reused each year to finance all of the purchases that occur. If people purchased $1,000,000 of goods and services in a particular year, and the (nominal) money supply were $1,000,000, for example, the velocity of money would be equal to 1; each dollar would be used an average of one time. If people purchased $1,000,000 of goods and services in a particular year, and the (nominal) money supply were $500,000, the velocity of money would be equal to 2; each dollar would be used an average of two times. The income velocity of money is defined as: V = P´ Y Y = M M P The quantity theory of money uses this definition to explain how and why the price level and the money stock are connected: M ´ V = P ´ Y. The classical incarnation of this theory assumes that both V and Y are fixed and, based on those assumptions, argues that any change in the money supply will cause a proportional change in the price level. Appendix The Baumol-Tobin formula for the transactions demand for money, THE DEMAND FOR MONEY M* = 177 tcY 2i uses some basic intuition and a small bit of math to find a formula for the amount of money people want to hold for the purpose of buying goods and services. First, notice that a person’s average balance (M) over a given period will be equal to 1 2 the amount of money they spend over that period divided by the number of times (n) they convert their other assets into money (e.g., withdraw cash from their savings account): Y 2n Next, observe that the opportunity cost of holding money is equal to the value of the next best opportunitythe rate of interest (i) paid by other assets. Each transfer is also assumed to cost an amount tc. M = The total cost of holding average balances Y 2n, then is: ( n ´ tc ) + iY 2n The best number of transactions is, of course, the one that minimizes this total cost. That number (n*), it turns out, is given by the following formula: n * = iY . 2tc Plugging this into our original equation M = Y 2n , we find that people will find it optimal, or best to hold average money balances M* = tcY . 2i KEY TERMS money M1 M2 M3 liquidity medium of exchange store of value unit of account standard of deferred payment real balances money illusion transactions motive precautionary motive speculative motive portfolio risky asset interest elasticity income elasticity flight out of money income velocity 178 CHAPTER 16 quantity theory of money quantity equation classical quantity theory GRAPH IT 16 It’s about time for a loose, relaxing exercise… don’t you think? This graph asks you to demonstrate the essential principles of precautionary money demand by drawing some loose wiggles on Chart 16–1. The idea behind the precautionary demand for money is that you want to hold enough so you don’t have to keep running to the bank, but don’t want to hold too much because of the opportunity cost. We’ve drawn a wiggly line representing a particular cash need. Assuming that we don't want to run out of money more than twice during the period on the graph, we took a straightedge and drew a dashed line as low as possible, with the wiggle peeking over it no more than twice. This solid line shows the precautionary demand for money. Your task is to draw a cash-need wiggle, with the cash needs generally having higher peaks. Then use a straightedge to draw in the money-demand line that is consistent with your not wanting to run out of money any more than twice during the period covered by the graph. Low money demand Time Chart 161 THE DEMAND FOR MONEY 179 THE LANGUAGE OF ECONOMICS 16 Liquidity An asset is liquid when it can be converted into goods or services quickly, at low cost, and with low risk. Cash is the ultimate liquid asset; it can be directly exchanged for goods and services anywhere. Checking accounts, or “demand deposits,” are quite liquid too. Stocks and bonds are less liquid. Both take time to sell, and therefore cannot as easily be used to buy goods or services. The prices of stocks and bonds also fluctuate. Imagine having to sell a share of stock every time you get a haircut or buy groceries; you might have to sell at a loss, simply to finance your purchase. Having to regularly convert either of these assets into goods and services would involve considerable risk. Ironically, one of the least liquid assets is a lake full of water. Lakes couldn’t possibly be easy to sell on short notice. REVIEW OF TECHNIQUE 16 Working with Natural Logarithms Before the days of calculators, tables of logarithms were used to speed up calculations. Today that is no longer necessary; few of us do our calculations by hand. Natural logarithms are still useful, however, because they are intimately connected to percentage changes: the change in the natural log of a variable is approximately equal to the percentage change of that variable. This is particularly useful when graphing one variable against another. If you graph the natural log of y (ln y) against the natural log of x (ln x), for example, the slope of your line will tell you the amount that y changes, in percentage terms, when x rises by 1 percent. A natural logarithm is formally defined as follows: X = ln Y if and only if x Y = e , where e is an irrational number (i.e., it goes on forever) approximately equal to 2.71828. Taking the natural log of the function e x gives you x; raising e to the power ln x also gives you x ( e x and ln x are inverse functions). There are some rules that will help you to work with natural logs: 1) ln(xy) ln x ln y 2) ln(x y) ln x ln y 3) ln(x y ) y ln x 4) ln(1 x) x (the symbol means " approximat ely equal to" ) 180 CHAPTER 16 FILL-IN QUESTIONS 1. The assets which form M1 are __________________ liquid than the assets which form M2. 2. Savings accounts are ___________________ liquid than Treasury bonds. 3. Holding money to reduce the risk associated with your portfolio of assets is an example of the ___________________ motive. 4. Holding money because you’re worried that something may come up that requires you to spend it is an example of the ___________________ motive. 5. Holding money in order use it to buy goods and services is an example of the ___________________ motive. 6. Ice cubes would not be a very good form of money because they would be a terrible ____________________. 7. Giant stone slabs might not be the best form of money because they would not be a very convenient ______________________. 8. When high inflation induces people to hold goods instead of assets, we say there is a _________________________. 9. The equation M ´ V = P ´ Y is called the ________________ equation. 10. The _______________________ of money measures the number of times the average dollar changes hands each year. THE DEMAND FOR MONEY 181 CROSSWORD ACROSS 1 2 Motive for holding money, people do 3 2 not want to convert illiquid assets into cash every time they make a purchase 5 Role of money, medium of ___ 7 Motive for holding money, just in case 4 5 6 9 Type of deposit, included in M2 but not M1 7 DOWN 8 1 Included in M1 3 Motive for holding money, 9 reduces portfolio risk 4 Measures number of times the average dollar changes hands in a year 6 Role of money, unit of ___ 8 Role of money, store of ___ TRUE-FALSE QUESTIONS T F 1. Cash is the most liquid asset of all. T F 2. Stocks are the most liquid asset of all. T F 3. An increase in income raises money demand. T F 4. Money demand adjusts immediately to changes in both income and the interest rate. T F 5. M1 is more liquid than M3. T F 6. M3 is more liquid than L. T F 7. People will hold as much money as they can get their hands on. T F 8. It is always better to hold more money than less. T F 9. If the money supply grows more quickly than output, it will cause inflation. T F 10. When the real interest rate increases, the demand for real money balances falls. 182 CHAPTER 16 MULTIPLE-CHOICE QUESTIONS 1. Currency is contained in a. M1 b. M2 c. M3 d. all of the above 2. T-bills (3-month Treasury bonds) are contained in a. M1 b. M2 c. M3 d. all of the above 3. Which of the following is the most liquid? a. M1 b. M2 c. M3 d. L 4. Which of the following is the least liquid? a. M1 b. M2 c. M3 d. L 5. Which of the following is the most commonly used measure of money? a. M1 b. M2 c. M3 d. L 6. Which of the following is not a function of money? a. medium of exchange b. unit of account c. store of value d. measure of greed 7. People will want to hold less money if there is/are a. high inflation b. low interest rates c. money illusion d. all of the above 8. In the long run, an increase in the money supply causes a. high real interest rates b. high output c. inflation d. all of the above 9. Money is: a. bills and coins b. bills, coins, and bank accounts c. anything people can exchange for goods and services. 10. In classical quantity theory, a. output is fixed b. velocity is fixed c. the price level can vary d. all of the above THE DEMAND FOR MONEY 183 CONCEPTUAL PROBLEMS 1. Why do you hold money? (How many of the motives for holding money can you identify with?) 2. What do you know of anything, aside from bills and coins, that has been used as money over the years? TECHNICAL PROBLEMS 1. If nominal GDP is $1,000,000 and the money supply (as measured by M2) is $500,000, what is the income velocity of money? 2. If output grows at an average of 3% per year and the money supply grows at an average of 8% per year, what must be the rate of inflation? 3. If you earn $100,000 per year, you pay $1.50 to withdraw money from your banking account, and the interest rate is 6%, how much money does the Baumol-Tobin model of the transactions demand for money suggest you will want to hold?