Brief-Didactic-Postpartum-Hemorrhage

advertisement

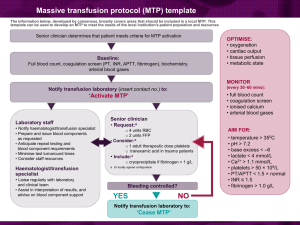

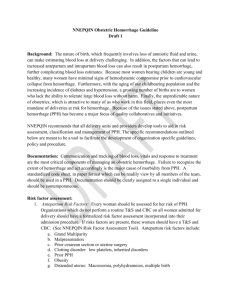

Brief Didactic: Postpartum Hemorrhage (PPH): A postpartum hemorrhage (PPH)is defined as either a 10% decrease in hematocrit between admission and the postpartum time period or the need for a blood transfusion. (ACOG 1998) The average blood loss at vaginal delivery and cesarean have been reported as 500mL and 1000mL respectively, but the estimated blood loss (EBL) at delivery is often significantly underestimated, often by as much as 50%, so you have to take into account both the estimated blood loss and the patient’s clinical picture. Also, remember that the hematocrit does not drop immediately in response to hemorrhage and will not equilibrate until nearly 12 hours later. So, the bottom line is, treat the patient not the labs. While there are definite risk factors associated with PPH, many of, such as obesity, placenta previa, placental abruption, etc, cannot be prevented. Because of this it is imperative that you recognize risk factors and are prepared should a PPH occur. Incidence: The incidence of PPH differs based on the type of delivery. PPH occurs after approximately 4% of vaginal deliveries and around 6% of cesarean deliveries and for women who have had a previous PPH, the risk of recurrence is as high as 10%. (Hall, 1985; Bonnar, 2000) Clinical Picture: Blood loss may be obvious at either vaginal or cesarean delivery. At times, though, it may be masked by amniotic fluid. As blood loss continues, however, the patient will become tachycardic and then hypotensive. She may also complain of shortness of breath, chest pain, or have an altered level of consciousness. Risk Factors: There are multiple risk factors for a patient developing a postpartum hemorrhage. Some of these include the following: Previous postpartum hemorrhage Multiple pregnancy Preeclampsia Prolonged second or third stage of labor Episiotomy Obesity Placenta abruption/previa Chorioamnionitis Birthweight > 4000gms Coagulopathy (Adapted from Bukowski, 2001) Causes: While there are multiple possible etiologies for PPH, the most common causes are uterine atony, retained placental tissue, and vaginal or perineal lacerations. Because of this, your initial treatment will be directed at ruling these out and treatment them should they be present. Prevention: Active management of the third stage of labor, which includes early cord clamping, oxytocin after delivery of the baby, and controlled cord traction, will prevent around 60% of PPH. (Bukowski, 2001) In addition to this, recognizing possible risk factors for PPH will allow you to have the proper personnel and equipment available should it occur. Treatment: The treatment of PPH should include efforts to both stabilize the mother and correct the underlying cause. The initial steps that should be taken are: Call for help (staff/anesthesia) IV access/fluid bolus (crystalloid) O2 by facemask Monitors (ensure you have someone to check BP/pulse) Place a foley catheter (when stabilized) to monitor urine output Determine cause Think of risk factors Check uterine tone Manually explore uterus for retained products. Examine for lacerations See the Figure 1 and Table 1 at the end for a treatment algorithm common medications that are used for treatment. Use of Blood Products: The use of blood products in patients who experience a significant postpartum hemorrhage can be life-saving. Patients who refuse blood transfusions, such as Jehovah’s witnesses, are at increased risk for maternal mortality from postpartum hemorrhage, with one study reporting a 44-fold increase in the risk of death from hemorrhage in this population. (Singla, 2002) However, because a transfusion involves some risk to the patient in terms of viral infection and transfusion reactions, treatment should be carefully considered and the appropriate products ordered. The most commonly used blood products on labor and delivery include packed red blood cells (PRBC), platelets, fresh-frozen plasma (FFP), and cryoprecipitate. Packed red blood cells (PRBCs): Most patients who suffer a significant hemorrhage will first receive a transfusion of PRBCs. They are indicated when a patient is hemodynamically unstable due to hemorrhage, especially if the hemoglobin level falls to less than 8 or 9 gm/dL. (Strong, 1997) While red blood cells are critical to transport oxygen to tissues in the body, care must be taken to monitor the patient for pulmonary edema when multiple transfusions are required. In general, you can expect the patient’s hemoglobin and hematocrit to increase by 3% and 1gm/dL per unit transfused. Platelets: Platelets should be transfused when there is evidence of hemorrhage as a result of either thrombocytopenia or platelet dysfunction. It may also be given in the face of massive transfusion of PRBC’s and abnormal bleeding as a dilutional thrombocytopenia can occur in this situation. While a patient is considered thrombocytopenic if their platelet count falls below 100,000/mm3, there is generally no problem with surgery (i.e. cesarean section) as long as the level does not fall to below 50,000/mm3. When a patient has a platelet count of less than 20,000/mm3, then they should be prophylactically transfused to prevent spontaneous bleeding. A single unit of platelets will increase the patient’s platelet count by approximately 7500/mm3. Fresh-frozen plasma (FFP): This is extracted from whole blood and contains both significant amounts of fibrinogen as well as multiple clotting factors. This is given when disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), vitamin K deficiency, or clotting factor deficiencies related to liver disease (and therefore vitamin K dependant clotting factors) are present. It can be expected to increase the patient’s fibrinogen level by 10-15 mg/dL per unit transfused. The goal of treatment with FFP in the presence of DIC or hypofibrinogenemia is a fibrinogen level of at least 100 mg/dL. It is important to think ahead when you encounter a significant postpartum hemorrhage as it takes at least 30 minutes for this blood product to be thawed and made available in most blood banks. (Of note, this is the only blood product with clotting factors V, XI, and XII.) Cryoprecipitate (Cryo): This blood product is a fraction of FFP that is rich in factors VII, XIII and fibrinogen, as well as von Willebrand’s factor. Because of the small amount of volume of each unit as compared to FFP (40mL vs 250mL) it is a more efficient way to raise the patient’s fibrinogen level. (This may be important in a patient with DIC with pulmonary edema secondary to fluid overload from multiple transfusions of PRBCs where you need to increase the fibrinogen level, but need to give as little additional volume as possible.) One unit of cryoprecipitate will increase the patient’s fibrinogen level by 10-15 mg/dL. In general, cryoprecipitate is given specifically for the treatment of von Willebrand’s disease, factor VII deficiency, or hypofibrinogenemia. See Table 2 for a comparison of all the different blood products Complications of Blood Transfusions: While the transfusion of blood products is often lifesaving in obstetrics, there are risks involved and these are important to discuss with patients when they are required. Adverse reactions: Adverse reactions that may occur with the transfusion of blood products generally either involve acute reactions or transmission of infectious agents to the recipient. Acute hemolytic transfusion reaction: This is most commonly a result of a clerical error resulting in the transfusion of incompatible blood products. It usually presents with a fever, which may be accompanied by nausea, emesis, dypsnea, back pain, and discomfort at the infusion site. It may progress to shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), or acute renal failure. The incidence of this type of reaction is, however, only 1:25,000. The risk of a fatal acute hemolytic reaction is much less at 1:600,000. (Menitove, 2000) If there is any suspicion of a hemolytic reaction, then the transfusion should be stopped and the blood product returned to the blood bank with a description of the possible reaction. Supportive care of the patient is indicated as well. Febrile non-hemolytic transfusion reaction: This type of reaction occurs approximately in 1:5,000-1:10,000 transfusions. (Menitove, 2000) When this occurs, the patient will generally experience a headache, shaking chills, or a fever within an hour of the transfusion beginning. If this occurs, then the transfusion should be stopped and the blood product sent back to the laboratory for testing. A hemolytic reaction should be ruled out by demonstrating no evidence of hemolysis (i.e. absence of hemoglobinemia, hemoglobinuria, and a negative direct antiglobulin test). Patients should receive acetaminophen for the fever and given supportive care. Anaphylactic reaction: Anaphylactic reactions, which are characterized by urticaria, angioedema dypsnea, nausea or abdominal cramping, and even shock, occur approximately 1:150,000 units of blood transfused. (Menitove, 2000) When this occurs, you should again, stop the infusion and send the products to the laboratory. Treatment of the patient involves stabilizing the airway and administering antihistamines and epinephrine as needed. Infections: Although all blood products are screened prior to administration to patients, the possibility of acquiring an infection, usually viral, still exists. Current estimates of these risks can be found in Table 3 below. FIGURE 1: TREATMENT ALGORITHM FOR POSTPARTUM HEMORRHAGE CONSIDER PPH RISK FACTORS ACTIVE MANAGEMENT OF 3RD STAGE OF LABOR POSTPARTUM HEMORRHAGE OCCURS - Call for help (staff/anesthesia) Obtain IV access Start IV fluids (crystalloid) – 1L BOLUS O2 by facemask (10L) Check vital signs (BP/Pulse/Pulse oximetry) Place a foley catheter to monitor urine output Send labs (CBC, PT/PTT/Fibrinogen) Blood products (PRBC, FFP, Cryoprecipitate) DETERMINE ETIOLOGY OF HEMORRHAGE Palpate Uterus Not palpable Check for and Treat Uterine Inversion if present Not Firm Firm Treat Uterine Atony Check for lacerations - Uterine massage - Medications (See Table 1) - Surgery or Uterine artery embolization (if stable enough) “-“ “+” Repair lacerations Check for retained placental fragments “-“ “+” Coagulopathy? “-“ Surgical Treatment - Manual removal - D&C if needed “+” - Consider placenta accreta, increta, percreta Treat Coagulopathy Table 1: Medications for Postpartum Hemorrhage MEDICATION Methylergonovine (Methergine) Prostaglandin F-2alpha (Hemabate) Misoprostol (Cytotech, PGE-1) DOSE 0.2mg IM OR into myometrium Q2-4 hours 250ug IM OR into myometrium Q15 minutes (up to 8 doses) 600ug-1000 mcg per rectum x 1 dose CONTRAINDICATIONS Hypertension, preeclampsia, asthma, Raynaud’s syndrome Asthma, renal disorders, pulmonary hypertension Known hypersensitivity to NSAIDs, active GI bleeding Table 2: Common blood products Blood product Contains Indications Volume (mL) Packed red blood cells Red cells, some plasma Increase red cell mass 300 Platelets Platelets, some plasma, few RBC/WBC Plasma, clotting factors Hemorrhage from thrombocytopenia 50 Fresh frozen plasma Cryoprecipitate Fibrinogen, factors V, VIII, XIII, von Willebrand’s factor Treatment of coagulation disorders Hemophilia A, von Willebrand’s disease, hypofibrinogenemia 250 40 Effect Increase Hct 3%/unit Increase Hgb 1gm/unit Increase platelet count by 7500mm3/unit Increase total fibrinogen 1015mg/dL/unit Increase total fibrinogen 10-15 mg/dL/unit Table 3: Incidence of viral infection after transfusion (per unit infused) INFECTION Hepatitis B Hepatitis C HIV 1-2 HTLV RISK 1:63,000 – 1:233,000 1:120,000 1:676,000 1:640,000 *Modified from Menitove, 2000 References: Bonnar J. Massive obstetric haemorrhage. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol, 2000; 14:1-18. Bukowski R, Hankins, GDV. Managing postpartum hemorrhage. Contemporary OB/GYN 2001 Sept; 46:92-102. Hall MH, Halliwell R, Carr-Hill R. Concomitant and repeated happening of complications of the third stage of labor. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1985; 92:732-738. Menitove JE. In Cecil Textbook of Medicine, 21st ed, Goldman (ed), W.B. Saunders Co, 2000. Singla AK, Lapinski RH, Berkowitz RL, Saphier CJ. Are women who are Jehovah's Witnesses at risk of maternal death? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Oct;185(4):893-5. Silver R, Depp R, Sabbagha RE, Dooley SL. Placenta previa: aggressive expectant management. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1984; 150:15. (*Didactic reprinted with permission from A Practical Manual to Labor and Delivery, © Shad Deering, 2009)