CPR Gobi Grasslands Policy

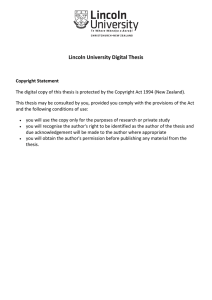

advertisement

Better Grasslands Management in Mongolia Benefits People and Nature In June and July 2010, a team of 35 national and international experts conducted a field study to measure the impacts on people and nature from the GTZ Gobi project in and around Gobi Gurvan Saikhan National Park. The GTZ Gobi project was part of the larger GTZ “Conservation and Sustainable Management of Natural Resources” program and ran from 1998 to 2006. About 5,000 people participated in the Gobi project which focused on community grasslands management and developing new income-generating activities for local people. The Gobi study site was chosen after a worldwide review of all known grassland projects. This project was believed by experts to have demonstrated how a conservation initiative can benefit people and nature. The study aim was to identify the project’s success factors that can be replicated in other grassland sites. About the Project The Gobi Gurvan Saikhan National Park, also known as the “Three Beauties of the Gobi”, is Mongolia’s largest national park. It was established in 1993 to protect endangered wildlife, endemic flora and significant paleontological sites. Recognizing the need for good pasture management, the GTZ project was established to improve pasture conditions and mitigate desertification. In order to achieve these goals, a comanagement approach was introduced focusing on improving cooperation and management of pastures with the local people, the park administration, and the local government. Another key element of the project was the formation of community organizations consisting of local herders and rural center inhabitants. Project activities included training to develop the management, financial and participatory planning capacity of stakeholders and practical skills to add value to livestock products and diversify livelihood strategies away from animal husbandry. As a result, new livelihood activities, such as dairy, meat processing and tourism, have flourished in the area. Methodology The team used quantitative and qualitative tools to measure the socioeconomic and ecological benefits. For the socioeconomic assessment, household surveys in 6 administrative districts spread across 2.3 million hectares generated the numbers. Focus group discussions and key informant interviews provided the stories behind the numbers. Matched control sites were chosen to provide the without-project baseline. This helped the team identify and exclude local changes that would have happened even without the project. A World Bank multi-dimensional definition of poverty that measured 10 indicators was used. The study team completed 280 household surveys, 8 focus group discussions, and 31 key informant interviews during 45 days of fieldwork. For the ecological assessment, changes were measured using satellite imagery supplemented by groundtruthing to compare project grazing areas with ecologically similar grazing areas that were not part of the project. Data from 76 sites (see map) for 10 years (2000 to 2009) were compiled and assessed for “Normalized Differential Vegetation Index” (NDVI). This is a proven way to measure photosynthetic activity of plants and obtain the density of aboveground biomass such as grass. The average seasonal NDVI characteristics and the summed growth season NDVI of the project and non-project pastures were also analyzed and compared. The field study methodology was one of the most rigorous ever undertaken to measure the impacts from an international development project on local people and nature. Results The pasture management improvements brought about positive ecological changes in project pastures compared to ecologically similar non-project pastures. Based on the NDVI observations, the average growing season of project pastures were longer than non-project pastures (~18 weeks vs. ~12 weeks), with earlier and faster greening up in spring. This allows a longer grazing season and quicker recovery of livestock from winter. Pasture lands of organized communities had on average 15% more grass biomass than pastures of non-organized herder households. Similar result was also obtained from a comparison of the project and non-project pastures before and after the project. Pasture grass growth in project areas was slightly worse than the non-project pastures before the project and an average of 14% better after the project. This indicated that more biomass for livestock is available now than before allowing them to survive drought in better condition than non-project sites. The project also provided important socioeconomic benefits for households that participated. The quantitative analysis shows that the median income among members of community organizations was 12% higher than non-members (US$ 2,498 vs. 2,222) because of the project. Income increased due to improved processing of animal products and the development of new income sources, such as vegetable growing. The co-management approach that was introduced by the project was also instrumental in strengthening the role of communities in decision-making processes particularly in pasture management plans and even social events. More of the community members’ children were also able to attend the university compared to non-members. In addition, improved access to credit has enabled community members to purchase hay and fodder that sustains their livestock during winter. 150 Aboveground biomass 140 130 120 110 100 90 80 70 60 Members 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 50 2000 Despite the significant improvements in both ecological and socioeconomic condition of communities, the impact of climate change that was a standout finding. Even with healthier livestock, new income sources, better pastures, more winter hay and fodder, and a community microcredit fund, the project communities still suffered devastating losses during the 2009-2010 dzud. Their current resources are not enough to cope with the increasingly severe summer droughts and harsh winters. Better winter shelters for livestock, continued improvements in the quality, and reductions in the quantity of livestock are the keys to making the Gobi pastoralists more resilient to climate change. Sum NDVI (Growth Season) Perhaps no group benefited more from the project than local women members. The project provided training to improve their skills and start new income generating activities, but more importantly, the project helped them have a greater voice which strengthened the social fabric of the community. Non-members Conclusions This study shows empirically that the GTZ Gobi project has achieved significant ecological and socioeconomic improvements that directly benefitted a bit more than 5,000 people. The majority of the benefits came from communities organizing themselves for better grasslands management, having a paid community liaison worker resident in each administrative district, and developing new income sources through greater value added and diversification. Four years after the project has ended, roughly half of the community liaison people continue to work even without pay from the project. This is one indicator of the high degree of local ownership of the project activities. Another is the large number of stakeholders who were involved in the project. This also underlines the significance of having a project with a process orientation rather than a product orientation and of allowing sufficient time for the project to achieve sustainable results. Creating local ownership, involving all stakeholders, and having a strong presence on the ground, are some of the successful factors identified by the study that can be replicated in other grassland sites or in community-based resource management project. The study also showed the importance of sharing a common goal and building trust among members in order to implement activities successfully and hold community members together. The presence of highly motivated and skilled community leaders was pivotal for ensuring and protecting the interests of all community members. This case study successfully demonstrated how co-management between herder community organizations, local government, and a national park can promote the health of grasslands, benefiting people and maintaining the world’s largest grassland ecosystem in the face of climate change. For the full study, click here (http://conserveonline.org/library/mongolia-gobi-grasslands-projectecological-and/@@view.html).