Oceans Neg - Millennial Speech & Debate

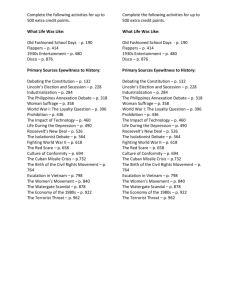

advertisement