Literary Arts: Short Story H`IT DID HURT Eugene N. Laughridge

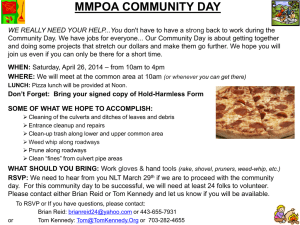

advertisement

Literary Arts: Short Story H’IT DID HURT Eugene N. Laughridge 2014 UNIFOUR SENIOR GAMES HI’T DID HURT Tom’s obituary didn’t say much, just that he was a native of the county, and when he had been born, and when he died. It didn’t tell how Tom, just like his daddy and his daddy’s daddy, and his great granddaddy and great-great granddaddy before him, was born and grew up in Jacktown. It didn’t say that everybody living around them was a cousin or closer, and that few of them ever saw much reason to go anywhere else to live. Jacktown didn’t have a church, or even a store, so no one from anywhere else ever saw any reason to cross the creek and the railroad tracks and go on up to Jacktown and stay, either. Oh, some people passed through, but it was mostly after dark on a Friday or a Saturday night and usually they were gone by morning. Most of them were young bucks looking to spend a little time at the house of one family that lived at the end of the dirt road that went as far up the mountain behind Jacktown as a road could go. That whole family was just a mama and a steady string of kids that kept coming along every year or so all the time Tom was growing up. It eventually became apparent that some of mama’s girls were mamas themselves, but no one, or at least no one outside that family, tried to keep up with it. The rest of the folks who might stop by Jacktown for awhile mostly came to pick up a taste or maybe a jar or two of corn likker. Most everybody in Jacktown made enough for themself, and some made enough to sell. The town did have a saw mill and most of the Jacktown boys worked off and on as sawyers or loggers. A few people worked some at one or another of the furniture factories or textile mills in the nearest town. Every family had a garden and a cow and chickens, so with that and money from logging or mill working, or likker or girls, Jacktown folks got by all right. Mostly they farmed a little or worked a little and hunted and fished a little and loafed a lot. Nobody up there saw much wrong with that plan. Like everybody else, Jacktown children were supposed to go to school until they were sixteen, at least, and that was about the only reason any of them crossed the tracks when they were young. Tom found out in his first year of school that people from the other side of the tracks were different from those from Jacktown. For one thing, most of the children who weren’t from Jacktown wore shoes even when the weather was warm. For another thing, they talked differently. Jacktown children might say, “H’it don’t matter” where other kids would say “It doesn’t matter.” There were a lot of things like that. The Jacktown kids could understand what the other-siders said and the other-siders could understand the boys and girls from Jacktown, but that didn’t stop the teachers from trying to change how the Jacktown children talked. “It,” the teachers would correct them every time one of the Jacktown children said “h’it.” Eventually some of the teachers would say, “Every time you say ‘h’it’ instead of ‘it,’ I am going to hit you.” They’d do it too, using a wooden ruler they carried around with them. When they did it, the kids from Jacktown would laugh at them. “H’it don’t hurt,” they’d say. Tom didn’t much like going to school, but it was easy enough for him and he was one of the few from Jacktown to go all the way through the twelfth grade. It was just before graduation that Tom was invited to a party for the first time. It was the only time he 2 had been invited anywhere or to do anything by one of his schoolmates from the other side of the tracks. Tom lacked at the desire or intention to attend but, later that day, the girl who was giving the party came up to him. “Hey Tom, I hope you’ll come to my party,” she said. She stepped so close to him that Tom could smell her, and it was unlike anyone or anything he had smelled before. He liked the way she smelled, and suddenly he felt warmer. “I really, really, especially hope you will come,” the girl said, and turned away. Tom didn’t know what to say or what to do at the party, but it didn’t matter. The girl spent most of the evening by his side and, as everyone was getting ready to leave, she took him by the hand and walked with him toward the road. “I’m really, really glad you came,” she told Tom when they stopped in the shadow of a tree near the road. “I really, really hope you’ll come to see me again soon.” She pulled Tom toward her and stood on her tiptoes and kissed him gently. Before Tom could recover, she turned and went back up the path toward her house. Tom started walking up to the road towards home. He looked at the moon big in the sky, and he felt the coolness of the air of the clear spring evening. He felt like shouting or singing, but he didn’t want to do the first and knew better than to try to do the second, so he just starting running. Without even thinking about it, he knew the time, 11:04, because he heard a train whistle. Every night at 11:06 the CC&O train reached the crossing of the road going up into Jacktown. It usually took five minutes, give or take depending upon the number of cars in the long train, for the caboose to cross. 3 Tom laughed. As he and his friends had done for fun many times, he ran up the hill and started to dash across the tracks just ahead of the oncoming train. On this night, however, the caboose didn’t finally cross the intersection until just before the sun came up the next morning. For the first time after hundreds of repetitions, Tom’s foot slipped on the gravel of the road bed, the toe of his right foot slipped under a rail of the track, and he wrenched his ankle. Before he could recover enough balance to lunge off the track, the train was upon him. The newspaper didn’t say much about Thomas Keller, just that he had died, a native of the county, when he had been born and that arrangements were to be determined. It didn’t tell how Tom had graduated from high school about the time that Vietnam came along and suddenly the young men from Jacktown started having to leave home. It didn’t tell about how Tom had gone to work in one of the furniture factories in town and, although he had refused an invitation to a party given by a local girl, he had later started seeing her and they were getting serious when he was drafted into the Army. Firing a rifle and doing a lot of walking and sleeping and other things outdoors were all familiar to him, and Tom did well in military training. Although there were a lot more rules and regulations than in school, there wasn’t anything he had to do to get by that was all that difficult. He figured he’d just go with the flow for the two years he had to serve and then go back to Jacktown. Like most draftees at that time, he finished basic and advanced infantry training and was in Vietnam almost before he knew it. An infantry company had just been pulled into Bien Hoa to integrate replacements while the remaining men in each platoon were recuperating, or getting R&R -- rest and relaxation -- as the 4 military called it, and he was absorbed into one of the rifle squads that had lost a couple of men in a firefight. Just doing his job the way he saw it for the next year, Tom earned two bronze stars and two purple hearts, along with his Combat Infantryman Badge. Following the second of his wounds, he spent a couple of months in an Army hospital outside Seattle fully recovering from head injuries. Then he was separated from the Army, and he started back to Jacktown a hero. After over fifty hours on trains and a bus, he arrived at the bus station nearest Jacktown about ten PM on a spring evening. He got off the bus behind a young woman, also from Jacktown. She had been a couple of years behind him in school, and she was returning from Fort Bragg to Jacktown to live with her family while her husband went overseas. She was pregnant and had with her a two year old boy and a three year old girl. The only taxi at the station was an old Ford coupe, but the woman and her children squeezed themselves into the back seat and Tom got into the front. It was only eleven PM when the taxi reached the bottom of the hill below the tracks but, as it approached the railroad crossing, the old Ford started laboring and then sputtering. The local road people were never been able to keep the pothole at the tracks from redeveloping, and it proved too much for the old Ford. By the time the engineer had seen the dark colored car on the tracks and had started to try to slow the train, the taxi driver and Tom had gotten out the car. The driver was helping the two children out behind the folding driver’s seat and Tom was assisting the pregnant mother through the other opening that was made smaller by the fact that both sides of the front seat were tilted forward at the same time. The young family made it, but Tom’s foot had become wedged between a rear tire and a crosstie and he never got clear of the car. 5 The newspaper didn’t say much about Thomas Keller, just that he had died a hero, a native of the county, when he had been born and that arrangements were to be determined. It didn’t tell how Tom had learned in the hospital that the only girlfriend he had ever had got married while he was in Vietnam. It didn’t tell how he had reenlisted in the Army and for the next 24 years, just as when he had first crossed the tracks from Jacktown to go to school, and again when he had left to go into the military, Tom had just gone along with all the things he had to do to get along. It didn’t tell how Tom, a 45-year-old retired U.S. Army Master Sergeant, came to be God-knows-where in Thonburi, across the Chao Phraya River from Bangkok, in the time of early morning when lack of sleep, fatigue, and other circumstances accruing from a long night on the town makes the whole world seem surreal. However, what he was doing there was what Tom was wondering about as he wandered among the tiny dark alleys, subconsciously following each until it intersected with one a little larger. By the time the first purpling of light from the oncoming day started to hit the smog of the city across the way, he had come out on a road along the bank of the river, and he followed it down to a bridge across to the oldest part of Bangkok. The brief purple haze had ceremoniously banished the relative quiet and coolness of the night, and the sun changed quickly from a saffron glow to a blazing ball of light that not even the smog could stop. When he reached a tiny open air riverside café on the other side of the bridge, Tom sat down in full view of Wat Arun, the huge Buddhist temple complex across the river. 6 “Singha, qu’at ya. Kaow phat,” he told the waiter who came to his table, and sat gazing at the river and the temple overlooking it. Gilded with thousands of multi-colored pieces of broken glazed pottery, the temple’s main cheddi and the smaller ones around it sparkled in the sun’s field of fire and, together with the hodgepodge of watercraft on the now busy river, completed Tom’s transition from one wonderland to another. The waiter returned with his order, and Tom dug into the heaping pile of steamed rice topped by a fried egg, and then poured the first glassful of beer from the brown one-liter bottle. “What brought you here?” asked the only other non-Thai person in the place, from where he sat a couple of tables away. Tom looked over at him and slowly shook his head. “There it is!” the man said, smiling and lifting his own bottle in salute before directing his attention back to the Thai woman sitting across his table from him. Chewing, Tom guessed that part of it was because Jacktown really was nothing to go back to. As he ate the rice and drank the beer, Tom thought about when his friend and platoon sergeant had died in Vietnam and how the men had coped by insisting that it didn’t mean anything, that it didn’t matter. That led to Tom’s memories of growing up and when his friends and he used to insist that h’it didn’t hurt. He guessed that things had meant something and things had hurt. Tom finished his meal and paid for another bottle of beer to take with him. He left the café and walked up the river to a railroad bridge. He walked out on the bridge a few feet and climbed up and sat on a railing and drank his beer and dozed, his back leaning against an upright and his legs wound between steel bars below the 7 railing. Suddenly Tom was awakened by the blast of a train whistle. He carefully extracted his legs from the steel gridwork and stepped down onto the tracks. The newspaper didn’t say much about Thomas Keller, just that he was a native of the county and when he had been born, and that he had retired from the Army, and that he had died in Bankgok, Thailand, and that arrangements were to be determined. end