Cal EM Neg v. Emory BD – Texas R7 - openCaselist 2015-16

advertisement

Cal EM Neg v. Emory BD – Texas R7

1NC

Extra T

Interpretation and violation – the resolution only mandates the legalization of

marihuana – the 1AC also has the states and territories establish the Cannabis

Exchange – that’s Extra-Topical

Vote negative –

First is presumption – the 1AC proves the resolution insufficient – no reason to vote

aff if their harms are dependent on an exchange system that’s not germane to the

topic

Second is limits – infinite number of actions can be taken alongside the plan which

means being negative impossible and obstructs topic education

Third is ground – allowing an extra action takes out all neg ground by tacking on

additional arbitrary plans which ruins clash

Governmentality K

Legalizing marijuana is a tactic of neoliberal governmentality that places the onus on

individuals to govern themselves while the government sits back and makes sure that

they’re doing it right – this increases state control through regulatory mechanisms

while minimizing its perception

O’Brien 13 - University of Wisconsin-Whitewater (February 25, Patrick, “Medical Marijuana and Social

Control: Escaping Criminalization and Embracing Medicalization” Deviant Behavior, 34: 423–443, Taylor

& Francis)

A latent outcome of this legal-medical system has been its adaptation to the new criminologies evidenced in late modern society (Garland

1996, 2001). The medicalization of cannabis has defined deviance down significantly (Moynihan 1993) and effectively reduced the demands

placed on the State’s criminal justice agencies. At the same time,

the State has increasingly embedded social controls

into the fabric of society , rather than inserting them from above in the form of sovereign command (Garland 2001).

Medical

dispensary owners, cultivators, investors, and employees, along with local politicians and affiliated

business owners, have

remained bound to State laws and policies, but have also been expected to proctor

themselves while government powers watch at a distance for a breakdown in control. The State has conceded

that it is unable to manage the illicit marijuana market alone and has redirected its control efforts away

from the sole authority of the police, the courts, and the prisons. The dispensary industry has provided the State

a situation in which it governs, but does not coercively control marijuana and its users. Instead, the State

manages the drug through the actors involved in the legal-medical industry, and has effectively mandated them as active partners in sustaining

and enforcing the formal and informal controls of the dispensary system.

resigned its power. On the contrary, it

The State

controls at an ostensibly distant fashion, but it has not

has retained its traditional command over the police and the prisons

while expanding its efficiency and capacity to control marijuana and its users . This new reality in crime control

has stratified itself across all facets of society, including its structural, cultural, and interactional dimensions. At the structural level, the

legal-medical model has reduced the strain of a substantial segment of society by institutionalizing

acceptable and lawful means of accessing marijuana, effectively shifting this population into an ecological

position where they can be watched and controlled . The groups once involved in the illicit market have

become visible, and the laws that govern the use, distribution, and production of cannabis have

actually become enforceable

by the State. Marijuana users have become patients, requiring a physician’s recommendation to con

sume the drug lawfully. The State has mandated what medical conditions warrant a registry card, monitoring people through licensing

applications, doctors’ files, government paperwork, and the medical marijuana registry. Dispensary owners have been required to grow 70%of

their own product, to provide live 24-hour surveillance camera feeds of their cultivation and distribution warehouses, and to subject

themselves to periodic inspection. Dispensary owners and employees have been fingerprinted and undergone extensive background checks,

and marijuana businesses only operate in State zoned locations. By

amassing knowledge about the social organization

of the marijuana industry and its users, the government has engaged in monitoring, aggregating, and

transmitting such information to law enforcement and the public. At the cultural level, the legal-medical system

has provided a greater degree of social order, stability, and integration by relocating marijuana users

into the fold of conventional norms and values. Cultural cohesion and conformity have been fostered

through legitimate business opera tions that cater to conventional lifestyles and work hours, that quell

concerns over safety and lawfulness, and reduce the alienation of a subculture of users. The State has

effectively aligned a once criminal population of people with dominant ideals of normality (Goffman 1983)

and dismantled a framework of deviant organization (Best and Luckenbill 1982) with

distinct ideol ogies and norms concerning

marijuana sales and use. The government has incorporated the norms and values of conventional society into the processes of

distributing and using cannabis, and now assists in controlling marijuana through the cultural transmission (Shaw and McKay 1972) of rituals

and sanctions now aligned with the normative social order. Both

of these macro- and meso-level shifts have augmented State

control of marijuana and its users at an interactional level. These structural and cultural changes have directly

influenced micro-level processes and mediated people’s differential associations and social learning

processes (Akers 2000; Sutherland 1949; Sutherland and Cressey 1955) as users have been increasingly socialized into a

conventional drug lifestyle. Marijuana users in the dispensary sys tem have decreased their contacts with deviant others and

increased their contacts with legitimate associations by purchasing lawfully from licensed distributors. Dispensary owners have

come to interact with banks, contractors, real estate firms, tax specialists, and lawyers because they exist in

legitimate occupational associations and lawful community relations. This legal-medical model has allowed the State to

further monitor interactional processes through receipts, taxes, and video surveillance. This continuous supervision

has led to growing discipline and normal ization. The State has prescribed conforming modes of

conduct upon marijuana users with new found power

(Foucault 1975). Zoning laws have mandated where transactions

occur, distribution laws have defined how much can be purchased, and monitored business hours have controlled the time sales occur. The

State has also strengthened individual bonds to society (Hirschi 1969) as a medical license protects users’ conventional

investments (i.e., education, career, and family) and caters to their time-consuming activities as they have decided the time, speed, and

location of their purchases. Finally, State medicalization of marijuana

has prompted people to endorse society’s rules as

progressively more politically and morally correct , since users are typically critical of cannabis

prohibition. This

legal-medical

system has also accommodated the ideals of neoliberalism . Through the

adaptive strategy of responsibilization (Garland 2001), the penalization

strategies (i.e., control mechanisms) regulating

marijuana have become increasingly privatized , operating through civil society. For example, although the

State has demanded 24-hour video surveillance over dispensary operations, it has also required these businesses to regulate

their own marijuana production and distribution, monitor their own employees and financial accounts, and direct their own

branding and promotional campaigns. Furthermore, by defining deviance down, marijuana has become legally sold through privately owned

dispensaries. In neoliberal fashion, marijuana has been deregulated for capital gain.

Biopower and neoliberalism combine to create a unique form of necropolitics that

drives endless extermination in the name of maintaining the strength of the market

Banerjee 6 - University of South Australia (Subhabrata Bobby, “Live and Let Die: Colonial Sovereignties

and the Death Worlds of Necrocapitalism,” Borderlands, Volume 5 No. 1,

http://www.borderlands.net.au/vol5no1_2006/banerjee_live.htm)

10. Agamben shows how sovereign power operates in the production of bare life in a variety of contexts:

concentration camps, 'human guinea pigs' used by Nazi doctors, current debates on euthanasia, debates on human rights

and refugee rights. A sovereign decision to apply a state of exception invokes a power to decide the

value of life, which would allow a life to be killed without the charge of homicide. The killings of mentally and physically handicapped

people during the Nazi regime was justified as ending a 'life devoid of value', a life 'unworthy to be lived'. Sovereignty thus becomes a decision

on the value of life, 'a power to decide the point at which life ceases to be politically relevant' (Agamben, 1998: 142). Life is

no more

sovereign as enshrined in the declaration of 'human' rights but becomes instead a political decision, an

exercise of biopower (Foucault, 1980). In the context of the 'war on terror' operating in a neoliberal economy, the

exercise of biopower results in the creation of a type of sovereignty that has profound implications for

those whose livelihoods depend on the war on terror as well as those whose lives become constituted as 'bare life' in the economy of the war

on terror. 11. However, it is not enough to situate sovereignty and biopower in the context of a neoliberal economy especially in the case of the

war on terror. In

a neoliberal economy, the colony represents a greater potential for profit especially as it is

this space that, as Mbembe (2003: 14) suggests, represents a permanent state of exception where sovereignty

is the exercise of power outside the law, where 'peace was more likely to take on the face of a war

without end'

and

where violence could operate in the name of civilization.

But these forms of necropolitical

power, as Mbembe reads it in the context of the occupation of Palestine, literally create 'death worlds, new and unique

forms of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to conditions of life conferring upon

them the status of theliving dead

' (Mbembe, 2003: 40). The

state of endless war is precisely the space

where profits accrue whether it is through the extraction of resources or the use of privatized militias or

through contracts for reconstruction. Sovereignty over death worlds results in the application of

necropower either literally as the right to kill or the right to 'civilize', a supposedly 'benevolent' form of

power that requires the destruction of a culture in order to 'save the people from themselves' (Mbembe,

2003:22). This

attempt to save the people from themselves has, of course, been the rhetoric used by the

U.S. government in the war on terror and the war in Iraq. 12. Situating necropolitics in the context of economy, Montag

(2005: 11) argues that if necropolitics is interested in the production of death or subjugating life to the power of death then it is possible to

speak of a necroeconomics - a space of 'letting die or exposing to death'. Montag explores the relation of the market to life and death in his

reading of Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations and Theory of Moral Sentiments. In Montag's reading of Smith, it is 'the dread of death, the great

poison to the happiness...which while it afflicts and mortifies the individual, guards and protects the society' (cited in Montag, 2005: 12). If

social life was driven solely by unrestrained self-interest then the fear of punishment or death through juridical systems kept the pursuit of

excessive self-interest in check, otherwise people would simply rob, injure and kill for material wealth. Thus, for Smith the universality of life is

contingent on the particularity of death, the production of life on the production of death where the intersection of the political and the

economic makes it necessary to exercise the right to kill. The market then, as a 'concrete form of the universal' becomes the 'very form of

universality as life' and requires at certain moments to 'let die'. Or as Montag theorizes it, Death establishes the conditions of life; death

as

by an invisible hand restores the market to what it must be to support life. The allowing of death of the

particular is necessary to the production of life of the universal. The market reduces and rations life; it not

only allows death ,

it demands death be allowed by the sovereign power , as well as by those who suffer it. In other

words, it

demands and required the latter allow themselves to die. Thus alongside the figure of homo sacer,

the one who may be killed with impunity, is another figure, one whose death is no doubt less spectacular than the first and is the object

of no memorial or commemoration: he who with impunity may be allowed to die, slowly or quickly, in the name of the

rationality and equilibrium of the market (Montag, 2005: 15). Montag, therefore, theorizes a necroeconomics

where the state becomes the legitimate purveyor of violence: in this scenario, the state can compel by

force by 'those who refuse to allow themselves to die'

(Montag, 2005: 15). However, Montag's concept of

necroeconomics appears to universalize conditions of poverty through the logic of the market. My concern however, is the creation of death

worlds in colonial contexts through the collusion between states and corporations. 13. If

states and corporations work in

tandem with each other in colonial contexts, creating states of exception and exercising necropower to

profit from the death worlds that they establish, then necroeconomics fails to consider the specificities of colonial capitalist practices. In this

sense, I would argue that necrocapitalism

emerges from the intersection of necropolitics and necroeconomics, as practices of

accumulation in colonial contexts by specific economic actors - multinational corporations for example - that

involve dispossession, death, torture, suicide, slavery, destruction of livelihoods and the general

management of violence. It is a new form of imperialism, an imperialism that has learned to 'manage

things better' . Colonial sovereignty can be established even in metropolitan sites where necrocapitalism may operate in states of

exception: refugee detention centres in Australia are examples of these states of exception (Perera, 2002). However, in the colonies (either

'post' or 'neo'), entire regions in the Middle East or Africa may be designated as states of exception.

The alternative is to refuse to imagine legality – only the formation of autonomous

geographies can challenge biopolitical neoliberalism

Pickerill & Chatterton 6 - Leicester University AND Leeds University (Jenny and Paul, “Notes

towards autonomous geographies: creation, resistance and self-management as survival tactics”

Progress in Human Geography30, 6 (2006) pp. 730–746)

In essence, autonomy is a coming together of theory and practice, or praxis. Hence, it is not solely an intellectual tool nor a guide for living;

it is a means and an end. Autonomous geographies represent the deed and the word, based around ongoing examples and

experiments. Autonomous

spaces are not spaces of deference to higher organizational levels

governmental organizations, political representatives or trade union officials. They

such as non-

are based around a belief that the

process is as important as the outcome of resistance , that the journey is an end in itself. As the Zapatistas say: ‘we

don’t know how long we have to walk this path or if we will ever arrive, but at least it is the path we have

chosen to take’. Autonomous geographies are based around a belief in prefigurative politics (summed up by

the phrase ‘be the change you want to see’), that

change is possible through an accumulation of small changes ,

providing much-needed hope against a feeling of powerlessness. Part of this is the belief in ‘doing it yourself ’ (see

McKay, 1998) or

creating workable alternatives outside the state . Many examples have flourished embracing ecological

direct action, free parties and the rave scene, squatting and social centres, and opensource software and independent media (Wall, 1999; Seel

et al., 2000; Plows, 2002; Chatterton and Hollands, 2003; Pickerill, 2003a; 2006). Resources are creatively reused, skills shared, and popular or

participatory education techniques deployed, aiming to develop a critical consciousness, political and media literacy and clear ethical

judgements (Freire, 1979). In

the terrain opened up by the failure of state-based and ‘actually existing

socialism’, autonomy allows a rethinking of the idea of revolution – not about seizing the state’s power

but, as Holloway (2002) argues, ‘changing the world without taking power’

(Vaneigem, 1979). Autonomy

does not

mean an absence of structure or order, but the rejection of a government that demands obedience

(Castoriadis, 1991). Examples of postcapitalist ways of living are already part of the present (Gibson-Graham, 1996). The documentation of the

‘future in the present’ has been a hallmark of work by anarchist, libertarian and radical scholars from Peter Kropotkin (1972) to Colin Ward

(1989) and Murray Bookchin (1996). Their

work looks for tendencies that counter competition and conflict,

providing alternative paths. Some of these disappear, others survive, but the challenge remains to find

them, encourage people to articulate, expand and connect them. Autonomous projects face the

accusation that, even if they do improve participants’ quality of living, they fail to have a transformative

impact on the broader locality and even less on the global capitalist system (DeFilippis, 2004). Consequently, in talking of local

resistance, Peck and Tickell (2002) suggest that ‘the defeat (or failure) of local neoliberalisms – even strategically important ones – will not be

enough to topple what we are still perhaps justified in calling “the system”’ (p. 401). However,

commentators make the mistake

of looking for signs of emerging organizational coherence , political leaders and a common programme that bids for

state power,

when the rules of engagement have changed . A plurality of voices is reframing the debate,

changing the nature and boundaries of what is taken as common sense and creating workable solutions

to erode the workings of market-based economies in a host of, as yet, unknown ways. Rebecca Solnit’s writings

on hope remind us that, while our actions’ effects are difficult to calculate, ‘causes and effects assume history

marches forward, but history is not an army . It is a crab scuttling sideways, a drip of soft water wearing

away stone’ (Solnit, 2004: 4).

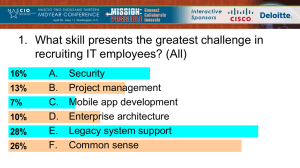

Cybersecurity Ptx

Cybersecurity’s the lone area of compromise—deal coming now

Swarts, 2-2—Phil, Washington Times, “Obama budget dedicates $14B to cybersecurity,”

http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2015/feb/2/obama-budget-dedicates-14b-to-cybersecurity/ -BR

The Obama administration aims to ramp up the federal government’s cybersecurity arsenal, requesting

nearly $14 billion in its 2016 budget proposal — about $1 billion more than in previous budgets — to

combat what many have come to view as an increasingly significant weakness in American security and

infrastructure. The increased funding comes after a series of high profile attacks, which has drawn

national attention to the issue, including a massive breach at Sony Pictures which the government said

was carried out by North Korea. Likewise in January, the Twitter and YouTube accounts for the U.S.

military’s CENTCOM — which oversees operations in Iraq and Afghanistan — was hacked by supporters

of the Islamic State, a terrorist group often known by the acronyms ISIS or ISIL. “Cyber threats targeting

the private sector, critical infrastructure and the federal government demonstrate that no sector,

network or system is immune to infiltration by those seeking to steal commercial or government

secrets,” the White House said in a statement. Though the president’s budget proposal was met with

widespread criticism by GOP lawmakers on Capitol Hill Monday, cybersecurity is likely going to be one

area where both parties find common ground. Much of the requested money will be split across major

government agencies that focus on cybersecurity, including the Departments of Homeland Security,

Justice and Defense.

The plan wrecks Obama’s PC

Jeremy Daw 12, J.D. from Harvard Law School, Dec 15 2012, “Marijuana Not A Priority For Obama,”

http://cannabisnowmagazine.com/current-events/politics/marijuana-not-a-priority-for-obama

Some hope for even more radical change. With the most recent polls suggesting that a majority of

Americans favor reform of pot laws, why not seize the moment and end federal prohibition entirely?

Obama could order the DEA to reschedule cannabis out of Schedule I to a less restrictive classification, which would effectively end the

conflict with the federal government in medical marijuana states. Such a move could harness political will for change and put the president on the winning side of

public opinion. But

such moves would have serious downsides . The politics of pot, rife with cultural and

political divisions since the tumultuous 1960s, remain bitterly divisive ; any politician who proposes

liberalization of cannabis laws risks becoming saddled with labels borne out of a long history of

ingroup/outgroup dynamics and which can rapidly drain a leader’s store of political capital . Given

Obama’s susceptibility to an even older tradition of racial stereotyping which associates cannabis use

with African Americans, any kind of green light to relaxed marijuana laws will cost the president dearly.

Obama has sufficient PC and momentum now—his push is vital to intel-sharing

Sorcher, 1-15—Sara, “Sony hack gives Obama political capital to push cybersecurity agenda (+video),”

Christian Science Monitor, http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Passcode/2015/0114/Sony-hack-givesObama-political-capital-to-push-cybersecurity-agenda-video --BR

“Sony hack gives Obama political capital to push cybersecurity agenda (+video)” Edward Snowden may

have doomed the prospects for cybersecurity legislation last Congress – but North Korea may revive

them in this one. After the leaks from the former National Security Agency contractor, privacy advocates

staunchly opposed cybersecurity bills that share information with the government, amid fears they

would increase the spy agency’s power to access and share even more private information from citizens.

The information-sharing bills stalled. Yet President Obama’s new push this week has so far been warmly

received on Capitol Hill – and on both sides of the aisle. Obama’s proposals, one week before his State

of the Union address, come after the destructive hack of Sony Pictures Entertainment, for which the

government has publicly blamed and sanctioned North Korea. It’s also on the heels of a maelstrom of

other high-profile data breaches last – including on Home Depot and JP Morgan Chase & Co. – and this

week’s brief takeover of the US military’s Central Command social media accounts by apparent Islamic

State supporters. All told, it may be enough momentum to break the logjam and give members of

Congress political cover to come together this session to support a controversial part of Obama’s

cybersecurity agenda: To give companies immunity from lawsuits if they share certain information about

cyber threats with the government with the Department of Homeland Security [DHS]. An informationsharing bill “has to pass this Congress,” Senate Intelligence Committee Chairman Richard Burr, a North

Carolina Republican, told Passcode. “It helps any time the president supports something.” Moving a

cybersecurity information-sharing bill “ has never been easy ,” he acknowledged, “but we’re committed

to go extremely quickly.” The Sony hack was a wake-up call on Capitol Hill, several lawmakers said. The

attackers not only stole private information, they destroyed company data and computer hardware, and

they also coerced Sony into altering its plans to release "The Interview," the comedy about the

assassination of the North Korean leaders. All of this may go a long way to persuade lawmakers that

mandating information sharing about cybersecurity threats will ultimately help defend private

companies. “I’m glad [Obama] is pushing to address cyber legislation,” said Republican Sen. Kelly Ayotte

of New Hampshire. “We’ve stalled in the past, and if you look at what happened with the Sony attack, I

think we can’t afford to stall anymore . I think his timing is right on here… . I haven’t talked to anyone in

Congress who has said, ‘This shouldn’t be a priority for us.’” Sen. Angus King, an independent on the

Intelligence Committee, agreed. “I think everybody realizes the urgency.” Maryland Democratic Rep.

Dutch Ruppersberger, who already reintroduced his version of information-sharing legislation this

session, said in a statement that, “President Obama and I agree we can no longer afford to play political

games while rogue hackers, terrorists, organized criminals and even state actors sharpen their cyber

skills.” However, just because “everybody’s on board with the idea of it” – as Republican Sen. John

McCain puts it – doesn’t mean it will be easy to make progress on this controversial and complicated

issue. “I have been to more meetings on cyber than any other issue in my time in the Senate, and gotten

the least amount of result,” said Senator McCain, who chairs the Armed Services Committee. There are

already divisions emerging this time around. McCain opposes the White House’s proposal to route

cyberthreat information through the Department of Homeland Secu*rity. He said the National Security

Agency should take that role. “I’m glad to see a proposal of theirs, for a change, and we’ll be glad to

work on it – just not rubber stamp it,” said McCain.

Intel-sharing provisions are critical to halting catastrophic cyberattacks

Lev-Ram, 1-21—citing DeWalt, CEO of FireEye, a leader in cyber security, protecting organizations

from advanced malware, zero-day exploits, APTs, and other cyberattacks. “Does President Obama's bid

to bolster cyber security go far enough?” Forbes, http://fortune.com/2015/01/21/obama-state-unioncybersecurity/?icid=maing-grid7|ie8-unsupported-browser|dl31|sec3_lnk3%26pLid%3D602263 –BR

Sharing real-time threat intelligence and indicators of compromise–both between the private sector and

the government and among the private sector–is a critical component of a pro-active security strategy.

The timely sharing of threat intelligence improves detection and prevention capabilities and provides

organizations with the ability to mitigate and minimize the adverse consequences of a breach. Sharing

also provides enhanced situational awareness for the community at large. FireEye research

demonstrates that over 70% of malware is highly targeted and used only once. To better manage risk

stemming from this continuously evolving threat environment, FireEye recommends that organizations

conduct robust compromise risk assessments, adopt behavioral based tools and techniques such as

detonation chambers, actively monitor their networks for advanced cyber threats, stand ready to rapidly

respond in the event of a breach and share threat intelligence and lessons learned through active

engagement in information sharing organizations. As a final preventative measure, organization should

obtain a cyber insurance policy to help with catastrophic repercussions of a breach.

Cyber threats outweigh the aff

Thamboo, 14—Visha, citing Richard Clarke, a former White House staffer in charge of counterterrorism and cyber-security, “Cyber Security: The world’s greatest threat,” 11-25,

https://blogs.ubc.ca/vishathamboo/2014/11/25/cyber-security-the-worlds-greatest-threat/ -- BR

After land, sea, air and space, warfare had entered the fifth domain: cyberspace. Cyberspace is arguably

the most dangerous of all warfares because of the amount of damage that can be done, whilst

remaining completely immobile and anonymous. In a new book Richard Clarke, a former White House

staffer in charge of counter-terrorism and cyber-security, envisages a catastrophic breakdown within

15 minutes . Computer bugs bring down military e-mail systems ; oil refineries and pipelines explode;

air-traffic-control systems collapse; freight and metro trains derail; financial data are scrambled; the

electrical grid goes down in the eastern United States; orbiting satellites spin out of control. Society soon

breaks down as food becomes scarce and money runs out. Worst of all, the identity of the attacker may

remain a mystery. Other dangers are coming: weakly governed swathes of Africa are being connected

up to fibre-optic cables, potentially creating new havens for cyber-criminals and the spread of mobile

internet will bring new means of attack. The internet was designed for convenience and reliability, not

security. Yet in wiring together the globe, it has merged the garden and the wilderness. No passport is

required in cyberspace. And although police are constrained by national borders, criminals roam freely.

Enemy states are no longer on the other side of the ocean, but just behind the firewall. The illintentioned can mask their identity and location, impersonate others and con their way into the

buildings that hold the digitised wealth of the electronic age: money, personal data and intellectual

property. Deterrence in cyber-warfare is more uncertain than, say, in nuclear strategy: there is no

mutually assured destruction, the dividing line between criminality and war is blurred and identifying

attacking computers, let alone the fingers on the keyboards, is difficult. Retaliation need not be confined

to cyberspace; the one system that is certainly not linked to the public internet is America’s nuclear

firing chain. Although for now, cyber warfare has not spiralled out of control, it is only a matter of

time , before cyber warfare becomes the most prominent type of attack, and the most deadly

because of its scope and anonymity .

Treaties Adv CP

Text: The United States federal government should make an international public

declaration acknowledging that they are in open breach of international drug treaties.

The United States should end all current legalization of marihuana and ban future

legalization, until international drug treaties are amended to allow legalization.

Small Farms

Squo solves – Illegality prevents investment from big agribusiness now

CNBC 10 (April 20, “Small Growers Or Corporate Cash Crop?” http://www.cnbc.com/id/36179260)

Agribusiness In The Wings?

Most large agribusiness producers and distributors wouldn’t comment on any

marijuana cultivation plans while it’s still largely illegal . Seed and agri-chemical maker Monsanto isn’t focused

on it, says spokesman Darren Wallis, adding that even if that changed tomorrow, development of a mass-scale crop takes time. “We focus on

major crops for food, feed and biofuels—corn, soybeans, cotton, canola, wheat, sugarcane and vegetables,” he says. “It takes eight to ten years

of investment to bring a biotech product to market.” Other

big food and agricultural firms would not comment, saying

the proposition was too hypothetical or inappropriate given the largely illegal current status of the drug.

Consumer demand will drive cannabis farmers to harvest indoors

Lewis 13 - senior lecturer in international history at Stanford (October 22, Martin W., “Unnecessary

Environmental Destruction from Marijuana Cultivation in the United States ”

http://geocurrents.info/place/north-america/northern-california/unnecessary-environmentaldestruction-marijuana-cultivation-united-states)

Growing sun-loving plants in buildings under artificial suns is the height of environmental and economic

lunacy. Outdoors, the major inputs—light and air—are free . Why then do people pay vast amounts of

money to grow cannabis indoors, regardless of the huge environmental toll

and the major financial costs? The

reasons are varied. Outdoor

cultivation is climatically impossible or unfeasible over much of the country.

Everywhere, the risk of detection is much reduced for indoor operations. Indoor crops can also be gathered year-round,

whereas outdoor harvests are an annual event. But the bigger spur for artificially grown cannabis

appears to be consumer demand . As noted in a Huffington Post article “ indoor growers … produce the bestlooking buds, which command the highest prices and win the top prizes in competitions .” In California’s

legal (or quasi-legal) medical marijuana dispensaries, artificially

grown cannabis enjoys a major price advantage, due

largely to the more uniformly high quality of the product. Journalists have been noting the environmental harm of indoor

marijuana cultivation for some time. Unfortunately, few people seem to care. In 2011, the San Francisco Bay Guardian reported that

environmental concerns were leading some consumers to favor outdoor marijuana, but any such changes have not yet been reflected in market

prices.

In the cannabis industry, as in the oil industry, ecological damage does not seem to be much of

an issue.

Industrial model is sustainable and small farms aren’t net better

-lower yields: 20-50%

-land use

-acidification

-soil erosion/tillage

-rotenone x fish

-zero-sum: aff model T/O

Miller 14 (Dr. Henry I. Miller, a physician and molecular biologist, was the founding director of the

FDA's Office of Biotechnology and is a research fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution,

“Organic Farming Is Not Sustainable,” May 15,

http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304431104579550002888434432, Groot)

You may have noticed that the organic section of your local supermarket is growing. Advocates tout organic-food production—in everything

from milk and coffee to meat and vegetables—as a "sustainable" way to feed the planet's expanding population. The Worldwatch

Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based environmental group, goes

so far as to say organic farming "has the potential

to contribute to sustainable food security by improving nutrition intake and sustaining livelihoods in rural areas, while

simultaneously reducing vulnerability to climate change and enhancing biodiversity ." The evidence

argues otherwise . A study by the Institute for Water Research at Ben-Gurion University in Israel, published last year in the journal

Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, found that "intensive organic

agriculture relying on solid organic matter, such as composted

manure that is implemented in the soil prior to planting as the sole fertilizer, resulted in significant down-leaching of

nitrate" into groundwater. With many of the world's most fertile farming regions in the throes of drought, increased nitrate in

groundwater is hardly a hallmark of sustainability. Moreover, as agricultural scientist Steve Savage has documented on the Sustainablog

website, wide-scale composting generates significant amounts of greenhouse gases such as methane and nitrous oxide. Compost may also

deposit pathogenic bacteria on or in food crops, which has led to more frequent occurrences of food poisoning in the U.S. and elsewhere.

of land and

conventional agriculture—impose

Organic farming might work well for certain local environments on a small scale, but its farms produce far less food per unit

water than conventional ones. The low yields of organic agriculture—typically 20%-50% less than

various stresses on farmland and especially on water consumption. A British meta-analysis published in the Journal of Environmental

Management (2012) found that "ammonia

emissions, nitrogen leaching and nitrous oxide emissions per

product unit were higher from organic systems" than conventional farming systems, as were

"land use, eutrophication potential and acidification potential per product unit." Lower crop yields are inevitable

given organic farming's systematic rejection of many advanced methods and technologies. If the scale of organic production

were significantly increased, the lower yields would increase the pressure for the conversion of

more land to farming and more water for irrigation, both of which are serious environmental issues. Another

limitation of organic production is that it disfavors the best approach to enhancing soil

quality—namely, the minimization of soil disturbances such as tilling, combined with the use of

cover crops. Both approaches help to limit soil erosion and the runoff of fertilizers and

pesticides. Organic growers do frequently plant cover crops, but in the absence of effective herbicides, often

they rely on tillage (or even labor-intensive hand weeding) for weed control. One prevalent myth is that organic

agriculture does not employ pesticides. Organic farming does use insecticides and fungicides to

prevent predation of its crops. More than 20 chemicals (mostly containing copper and sulfur) are

commonly used in the growing and processing of organic crops and are acceptable under U.S.

organic rules. They include nicotine sulfate, which is extremely toxic to warm-blooded animals, and

rotenone , which is moderately toxic to most mammals but so toxic to fish that it's widely used for the mass

poisoning of unwanted fish populations during restocking projects. Perhaps the most illogical and least sustainable

aspect of organic farming in the long term is the exclusion of " g enetically m odified o rganism s ," but only

those that were modified with the most precise and predictable techniques such as gene

splicing. Except for wild berries and wild mushrooms, virtually all the fruits, vegetables and grains in our diet have

been genetically improved by one technique or another, often through what are called wide crosses, which move

genes from one species or genus to another in ways that do not occur in nature. Therefore, the exclusion from organic

agriculture of organisms simply because they were crafted with modern, superior techniques makes no sense. It also denies

consumers of organic goods nutritionally improved foods, such as oils with enhanced levels of omega-3 fatty acids. In recent decades,

we have seen advances in agriculture that have been more environmentally friendly and

sustainable than ever before. But they have resulted from science-based research and tech nological

ingenuity by farmers, plant breeders and agribusiness companies , not from social elites opposed to

modern insecticides, herbicides, genetic engineering and "industrial agriculture."

Small farms fail

McWilliams 09 (James, historian at Texas State University, 10/7,

http://freakonomics.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/10/07/let-the-farmers-market-debatecontinue/?apage=2)

Some academic critics are starting to wonder. Writing in the Journal of Rural Studies, sociologist C. Clare

Hinrichs warns that “[m]aking ‘local’ a proxy for the ‘good’ and ‘global’ a proxy for the bad may

overstate the value in proximity.” Building on this suspicion, she acknowledges that many small farms

are indeed more sustainable than larger ones, but then reminds us that “Small scale, ‘local’ farmers are

not inherently better environmental stewards.” Personal experience certainly confirms my own inability

to make such a distinction. Most of us must admit that in many cases we really haven’t a clue if the local

farmers we support run sustainable systems. The possibility that, as Hinrichs writes, they “may lack the

awareness or means to follow more sustainable production practices” suggests that the mythical sense

of community (which depends on the expectation of sound agricultural practices) is being eroded. After

all, if the unifying glue of sustainability turns out to have cracks, so then does the communal

cohesiveness that’s supposed to evolve from it. And this is not a big “If.” “[W]hile affect, trust, and

regard can flourish under conditions of spatial proximity,” concludes Hinrichs, “this is not automatically

or necessarily the case.” At the least, those of us who value our local food systems should probably take

the time to tone down the Quixotic rhetoric and ask questions that make our farmer friends a little

uncomfortable.

Tech development solves agriculture

Thompson 11 –senior fellow for The Chicago Council on Global Affairs and professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at UrbanaChampaign. (Robert, “Proving Malthus Wrong, Sustainable agriculture in 2050”

http://scienceblogs.com/tomorrowstable/2011/05/proving_malthus_wrong_sustaina.php)//SQR

Tools available today, including plant breeding and biotechnology, can make presently unusable soils productive

and increase the genetic potential of individual crops - enhancing drought and stress tolerance, for

example - while also producing gains in yields. Existing tools can also internalize plants' resistance to disease, and

even improve a plant's nutritional content - meaning consumers can get more nutritional value without increasing their

consumption. Furthermore, modern high-productivity agriculture minimizes farmers' impact on the

environment. Failure to embrace these technologies will result in further destruction of remaining forests. Adoption of

technologies that produce more output from fewer resources has been hugely successful from an

economic standpoint: prior to the price spike in 2008, there was a 150-year downward trend in the real price of food. The jury is still

out on whether the long-term downward trend will resume, prices will flatten out on a new higher plateau, or they will trend upward in the

future. The key is investing in research in the public and private sectors to increase agricultural productivity faster than global demand grows.

Long ago, British scholar Thomas Malthus

predicted that the human population would eventually outgrow its

ability to feed itself. However, Malthus has been proven wrong for more than two centuries precisely

because he underestimated the power of agricultural research and technology to increase

productivity faster than demand. There is no more reason for Malthus to be right in the 21st century

than he was in the 19th or 20th - but only if we work to support, not impede, continued agricultural

research and adoption of new technologies around the world.

Countries will cooperate over food

Burger et al. 10 -Development Economics, Corresponding author, Wageningen University (Kees, “Governance of the world food

system and crisis prevention” http://www.stuurgroepta.nl/rapporten/Foodshock-web.pdf ) //SQR

Both European water and agricultural policies are based on the belief that there will always be cheap food aplenty on the world market. A

recent British report 23 reflects this optimism. Although production is now more prone to world market price shocks, their effects on farm

incomes are softened by extensive income supports (van Eickhout et al. 2007). Earlier, in a 2003 report, a European group of agricultural

economists wrote: Food

security is no longer a prime objective of European food and agricultural policy. There

is no credible threat to the availability of the basic ingredients of human nutrition from domestic and

foreign sources. If there is a food security threat it is the possible disruption of supplies by natural disasters

or catastrophic terrorist action. The main response necessary for such possibilities is the appropriate

contingency planning and co-ordination between the Commission and Member States (Anania et al. 2003). Europe, it

appears, feels rather sure of itself, and does not worry about a potential food crisis. We are also not aware of any

special measures on standby. Nevertheless a fledgling European internal security has been called into being that can be deployed should (food)

crises strike. The Maastricht Treaty (1992) created a quasi-decision-making platform to respond to transboundary threats. Since 9/11 the

definition of what constitutes a threat has been broadened and the protection capacity reinforced. In the Solidarity Declaration of 2003

member states promised to stand by each other in the event of a terrorist attack, natural disaster or human-made calamity (the European

Security Strategy of 2003). Experimental

forms of cooperation are tried that leave member-state sovereignty

intact, such as pooling of resources. The EU co-operates in the area of health and food safety but its mechanisms remain

decentrslised by dint of the principle of subsidiarity. The silo mentality between the European directorates is also unhelpful, leading to

Babylonian confusion. Thus, in the context of forest fires and floods the Environment DG refers to ‘civil protection’.

Emissions in developing countries make CO2 reduction impossible – modeling is

irrelevant

Koetzle, 08 – Ph.D. and Senior Vice President of Public Policy at the Institute for Energy Research

(William, “IER Rebuttal to Boucher White Paper”, 4/13/2008,

http://www.instituteforenergyresearch.org/2008/04/13/ier-rebuttal-to-boucher-white-paper/)

For example, if the United States were to unilaterally reduced emissions by 30% or 40% below 2004 levels[8] by 2030; net global CO2 emissions

would still increase by more than 40%. The reason is straightforward: either of these reduction levels is offset by the increases in CO2 emissions

in developing countries. For example, a 30% cut below 2004 levels by 2030 by the United States offsets less than 60% of China’s increase in

emissions during the same period. In fact, even if

the United States were to eliminate all CO2 emissions by 2030,

without any corresponding actions by other countries, world-wide emissions would still increase by 30%.

If the United States were joined by the other OECD countries in a CO2 reduction effort, net emissions

would still significantly increase. In the event of an OCED-wide reduction of 30%, global emissions increase by 33%; a reduction of

40% still leads to a net increase of just under 30%. Simply put, in order to hold CO2 emissions at 2004 levels, absent any reductions by

developing nations like China and India, all OECD emissions would have to cease.[9] The lack of participation

by all significant

sources of GHGs not only means it is unlikely that net reductions will occur; it also means that the cost

of meaningful reductions is increased dramatically. Nordhous (2007) for example, argues that for the “importance of nearuniversal participation to reduce greenhouse gases.”[10] His analysis shows that GHG emission reduction plans that include, for example, 50%

of world-wide emissions impose additional costs of 250 percent. Thus, he find’s GHG abatement plans like Kyoto (which

does not include significant emitters like the United States, China, and India) to be “seriously flawed” and “likely to be ineffective.” [11] Even if

the United States had participated, he argues that Kyoto would make “but a small contribution to slowing global warming, and it would

continue to be highly inefficient.”[12]The data on emissions and economic analysis of reduction programs make it clear that GHG emissions are

a global issue. Actions

by localities, sectors, states, regions or even nations are unlikely to effectively reduce

net global emissions unless these reductions are to a large extent mirrored by all significant emitting

nations.

No impact – empirics

Willis et. al, 10 [Kathy J. Willis, Keith D. Bennett, Shonil A. Bhagwat & H. John B. Birks (2010): 4 °C and

beyond: what did this mean for biodiversity in the past?, Systematics and Biodiversity, 8:1, 3-9,

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/14772000903495833, ]

The most recent climate models and fossil evidence for the early Eocene Climatic Optimum (53–51 million

years ago) indicate that during this time interval atmospheric CO2 would have exceeded 1200 ppmv and

tropical temperatures were between 5–10 ◦ C warmer than modern values (Zachos et al., 2008). There is also

evidence for relatively rapid intervals of extreme global warmth and massive carbon addition when

global temperatures increased by 5 ◦ C in less than 10 000 years (Zachos et al., 2001). So what was the

response of biota to these ‘climate extremes’ and do we see the large-scale extinctions (especially in the

Neotropics) predicted by some of the most recent models associated with future climate changes (Huntingford

et al., 2008)? In fact

opposite.

the fossil record for the early Eocene Climatic Optimum demonstrates the very

All the evidence from low-latitude records indicates that, at

least in the plant fossil record, this was one of

the most biodiverse intervals of time in the Neotropics (Jaramillo et al., 2006). It was also a time when the tropical

forest biome was the most extensive in Earth’s history, extending to mid-latitudes in both the northern

and southern hemispheres – and there was also no ice at the Poles and Antarctica was covered by

needle-leaved forest (Morley, 2007). There were certainly novel ecosystems, and an increase in community

turnover with a mixture of tropical and temperate species in mid latitudes and plants persisting in areas

that are currently polar deserts. [It should be noted; however, that at the earlier Palaeocene–Eocene Thermal

Maximum (PETM) at 55.8 million years ago in the US Gulf Coast, there was a rapid vegetation response

to climate change. There was major compositional turnover, palynological richness decreased, and regional extinctions occurred

(Harrington & Jaramillo, 2007). Reasons for these changes are unclear, but they may have resulted from continental drying, negative feedbacks

on vegetation to changing CO2 (assuming that CO2 changed during the PETM), rapid cooling immediately after the PETM, or subtle changes in

plant–animal interactions (Harrington & Jaramillo, 2007).]

Treaties

States don’t violate treaties

Humphreys 13 – prof @ stanford

(Keith, “Can the United Nations Block U.S. Marijuana Legalization?” 11/15,

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/keith-humphreys/can-the-united-nations-bl_b_3977683.html)

1. Is the U.S. currently in violation of the UN treaties it signed agreeing to make marijuana illegal? No. The U.S. federal

government is a signatory to the treaty, but the States of Washington and Colorado are not. Countries with

federated systems of government like the U.S. and Germany can only make international commitments regarding their national-level policies.

Constitutionally, U.S. states are simply not required to make marijuana illegal as it is in federal law. Hence,

the U.S. made no such

commitment on behalf of the 50 states in signing the UN drug control treaties.¶ Some UN officials believe that the

spirit of the international treaties requires the U.S. federal government to attempt to override state-level marijuana legalization. But in

terms of the letter of the treaties, Attorney General Holder's refusal to challenge Washington and Colorado's marijuana

policies is within bounds.

But the plan does and creates a precedent for a pick and choose approach to

international law which spills over across all treaty areas – turns case.

Hasse 13 [10/14/13, Heather Hasse is a New York consultant for International Drug Policy Consortium

and the Harm Reduction Coalition, “The 2016 Drugs UNGASS: What does it mean for drug reform?”

http://drogasenmovimiento.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/13-10-14-the-2016-drugs-ungasse28093what-does-it-mean-for-drug-reform_.pdf]

But why? With all of the progress made in reform around the world lately, many – especially in the US – are asking if the UN is even

relevant to domestic drug reform at this point. With the recent marijuana laws passed in Colorado and

Washington and the proposed legislation in Uruguay – not to mention decriminalization measures enacted in Portugal and a

growing number of other countries – reform seems inevitable. At some point, the argument goes, the UN system will

simply be overtaken by “real world” reform on the ground. Why even bother with advocacy at the

UN? This is not an easy question to answer; however, I truly believe that to be effective, reform efforts must be made at

every level

– locally, nationally, and

globally . It may be true that reform efforts in the US and around the world have made significant

progress in the last 10 years. But there is still a long way to go – marijuana

is still not completely legal anywhere in the

world (despite state laws to the contrary, marijuana still remains illegal under federal law throughout

the US), and many human rights abuses continue to be carried out against drug users throughout the

world in the name of drug control. Meanwhile, the international drug control treaties – the 1961 Single Convention

on Narcotic Drugs and its progeny – remain

in place and, in fact, enjoy nearly universal adherence

by 184 member states.

That so many countries comply – at least technically, if not in “spirit” – with the international drug treaty

system, shows just how highly the international community regards the system.

As well it should – the

UN

system is invaluable and even vital in many areas, including climate change, HIV/AIDS reduction, and,

most recently, the Syrian chemical weapons crisis (and don’t forget that the international drug treaty system also governs

the flow of licit medication). While it is not unheard of for a country to disregard a treaty, a system in which countries pick and

choose which treaty provisions suit them and ignore the rest is, shall we say, less than ideal . But beyond

the idea of simple respect for international law, there are practical aspects of reform to consider. The drug problem is a global one, involving

not only consuming countries but producing and transit countries as well. Without global

cooperation, any changes will at

best be limited (marijuana reform in Washington and Colorado hardly affects the issue of human rights abuses in Singapore or the

limitations on harm reduction measures in Russia). At worst, reform efforts enacted ad hoc around the world could be

contradictory and incompatible - as might be the result if, for example, Colombia and the US opted for a regulated market without

the cooperation of Costa Rica or Honduras, both transit countries. Finally,

no matter what you think about the treaties and

the UN drug control system, or how significant you believe them to be in the grand scheme of things,

they are here for the time being, and are necessary to any discussion about drug reform.

U.S. I-Law credibility is terminally dead – way too many alt causes

Carasik 14 (Lauren Carasik, clinical professor of law and the director of the international human rights

clinic at the Western New England University School of Law, Al Jazeera, “Human rights for thee but not

for me”, 3/12/14, http://america.aljazeera.com/opinions/2014/3/the-us-lacksmoralauthorityonhumanrights.html)

Last month U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry unveiled the State Department’s comprehensive annual assessment of human rights around the

globe. It painted a grim picture of pervasive violations. Notably absent from the report, however, was any discussion of Washington’s own

record on human rights. The report elicited sharp rebukes from some of the countries singled out for criticism. Many of them

questioned the United States’ legitimacy as self-appointed global champion of human rights. China

issued its own report, 154 pages long, excoriating the U.S. record on human rights and presenting a list of

Washington’s violations. Egypt’s Foreign Ministry called the report “unbalanced and nonobjective” and

censured the U.S. for appointing itself the world’s watchdog. Ecuador, Russia and Iran also criticized the report. By

signaling that the world cares about human rights violations, the report provides a useful tool for advocates. While the omission of any

internal critique is unsurprising, that stance ultimately undermines the State Department’s goals of promoting

human rights abroad. Abuses unfolding around the world demand and deserve condemnation. But it is difficult for the U.S. to

don the unimpeachable mantle, behave hypocritically and still maintain credibility. North-south schism It is

tempting to dismiss the scolding as retaliatory howls by authoritarian states, but their critiques have long been echoed by others. Pointing to

simmering divisions over human rights standards, China argued that developing countries face a different set of challenges from their more

developed counterparts. This ideological debate has permeated rights discourse and often underscores a north-south schism. The divide has its

roots in the history of human rights. In 1945, still reeling from the atrocities of World War II, world powers gathered in Paris to forge a

multilateral agreement that would form “the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.” Those principles were enshrined in the

nonbinding Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). The U.N. then adopted two covenants that would have the force of law: one

focused on civil and political rights and the other on economic, social and cultural rights. Together with the UDHR, they form the International

Bill of Human Rights. The covenants were meant to be universal, interdependent and indivisible and equally treated, but they do not exist in a

political vacuum. Although the

U.S. was instrumental in creating this international framework, it has resisted conforming to

many of the norms for which there is an emerging international consensus. The U.S. holds sacred its commitment

to civil and political rights, such as those protected by its robust and revered Bill of Rights and proclaims itself a beacon of freedom and justice

in the world. Critics argue that the rhetoric exceeds the reality on the ground. Economic and social rights are far more contested, in part

because they require affirmative duties that affect resource allocation: States must take progressive action toward providing housing, food,

education, health care and a host of other rights. The

U.S. purports to be evenhanded. But geopolitical interests

influence the tenor and content of its assessments, leading some critics to accuse the U.S. of sacrificing

human rights at the altar of political expediency. For example, the U.S. has been accused of blunting its appraisal of allies

such as Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Mexico, Uzbekistan, Honduras and Israel. Economic interests also factor in. Critics decry the sale of

arms to countries that by Washington’s own assessment are complicit in human rights abuses. While

politically and economically self-interested maneuvering is inevitable, not all countries issue an ostensibly definitive and unvarnished report on

the state of global human rights. In December during Human Rights Week, U.S. President Barack Obama issued a proclamation reaffirming the

United States’ “unwavering support for the principles enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” Yet

global headlines

are dominated by high-profile U.S. human rights transgressions — indefinite detention at

Guantánamo Bay, torture, extraordinary rendition, extrajudicial assassination by drones that claims the

lives of innocents in addition to its targets, the aggressive pursuit of whistle-blowers and data collection that

violates privacy both at home and abroad. Advocates criticize a litany of other human rights abuses,

such as mass incarceration (the U.S. has 5 percent of the world’s population but 25 percent of its inmates, with disproportionate

representation among minority groups), the death penalty (including post-execution revelations that raise serious doubt about already

questionable convictions), racial profiling, the disenfranchisement of felons, sentences of life without parole for

juvenile offenders, gun violence, solitary confinement, the shackling of pregnant inmates and many

others. The New York–based Human Rights Watch says these violations disproportionately affect minority

communities. “Victims are often the most vulnerable members of society: racial and ethnic minorities, immigrants, children, the elderly,

the poor and prisoners,” it said in its annual report on the U.S. last year. Evading treaties Aside from specific human rights

violations, the U.S. has been singularly unwilling to ratify key international human rights instruments,

which reinforces its status as an outlier in the field. These include its refusal to ratify the Convention

to Eliminate All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (only seven other countries are not parties to it), the

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Convention on Rights of the Child

(ratified by all states except the U.S., Somalia and South Sudan) and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with

Disabilities. The U.S. has also failed to ratify the American Convention on Human Rights, a regional

framework on human rights in the Americas. It has ratified only two of the International Labor Organization’s eight

fundamental conventions. Washington’s refusal to ratify the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

(ICC) has provoked particular consternation. The international community has a profound interest in

deterring the most violent abuses by ending impunity for war crimes, crimes against humanity and

genocide. The ICC was created to promote accountability for these crimes, which are, for a complex and interrelated constellation of

reasons, notoriously difficult to prosecute in domestic courts. But the U.S. will not submit to its jurisdiction, citing a number of

concerns, including that the court would be subject to political manipulation and lack accountability to the U.N. and that submitting to it would

violate state sovereignty. Some critics claim that it is the U.S. that fears being held to account in the international arena for the global

expansion of its military and its possible commission of war crimes. To be fair, the ICC has its critics as well, who contest both its legitimacy and

its efficacy. Subjects of complaint include its perceived preoccupation with African criminals, its slow pace of prosecutions and questions about

how and when the international community should protect citizens of a sovereign state against atrocities. But the U.S. refusal to sign the Rome

Statute, which established the ICC, undermines the principle that each and every country must be accountable to certain universal standards if

they are to be rendered meaningful. American exceptionalism U.S. intransigence is often cloaked behind lofty conception of American

exceptionalism — the idea that the U.S. embodies the standards of liberty and democracy to which other countries should aspire. Claiming to

stand at the apex of democracy and human rights,

global rights framework.

the U.S. exempts itself from surrendering its sovereignty to any

Resistance to the adoption of international norms is not monolithic within the country, however. In a sign

of retreat from these principles at a local level, some states and municipalities are embracing international human rights standards. The

“Bringing Human Rights Home” report by the Human Rights Institute at Columbia School of Law evinces the willingness of some local

governments to incorporate universal human rights standards, including economic and social rights that the U.S. has so far declined to validate.

In 2012 former U.S. President Jimmy Carter urged the U.S. to reclaim its moral high ground, lamenting that “America’s violation of international

human rights abets our enemies and alienates our friends.” Upholding universal, inalienable and enforceable human rights standards in a

pluralistic and increasingly entangled world is no easy task. But the domestic and international human rights movements are driven by the

urgent goal of protecting the dignity of all human beings — including those at the margins who are powerless, poor, invisible and persecuted.

The U.S. would have more credibility in promoting those principles if it reflected on its own

transgressions. Naming and shaming by international actors is an essential tool for advancing human rights. But it assumes both the moral

authority to sit in judgment and the humility to be self-critical.

International law fails

Hiken 12, "The Impotence of International Law", Associate Director Institute for Public Accuracy, Luke,

7-17, http://www.fpif.org/blog/the_impotence_of_international_law

Whenever a lawyer or historian describes how a particular action “violates international law” many people stop listening or reading further. It

is a bit

alienating to hear the words “this action constitutes a violation of international law” time and time again

– and especially at the end of a debate when a speaker has no other arguments available. The statement is inevitably followed by: “…and it is a war crime and it

denies people their human rights.” A

plethora of international law violations are perpetrated by every major power

in the world each day, and thus, the empty invocation of international law does nothing

but reinforce our

own sense of impotence and helplessness in the face of international lawlessness. The

United States, alone, and on a daily basis

violates every principle of international law ever envisioned: unprovoked wars of aggression; unmanned

drone attacks; tortures and renditions; assassinations of our alleged “enemies”; sales of nuclear

weapons; destabilization of unfriendly governments; creating the largest prison population in the world – the

list is virtually endless. Obviously one would wish that there existed a body of international law that could put an end to these abuses, but

such laws

exist in theory, not in practice. Each time a legal scholar points out the particular treaties being

ignored by the superpowers (and everyone else) the only appropriate response is “so what!”

or “they always say that.”

If there is no enforcement mechanism to prevent the violations, and no military force with the power to

intervene on behalf of those victimized by the violations, what possible good does it do to invoke

principles of “truth and justice” that border on fantasy? The assumption is that by invoking human rights principles, legal scholars ho pe to reinforce the

importance of, and need for, such a body of law. Yet, in reality, the invocation means nothing at the present time, and goes

nowhere. In the real world, it would be nice to focus on suggestions that are enforceable, and have some potential to prevent the atrocities taking place

around the globe. Scholars who invoke international law principles would do well to add to their analysis, some form of action or conduct at the present time that

might prevent such violations from happening. Alternatively,

praying for rain sounds as effective

and rational as

citing

international legal principles to a lawless president, and his ruthless military.

Gridlock dooms effectiveness

Goldin 13 – Ian, Director of the University of Oxford’s Oxford Martin School world-leading centre of

pioneering research, debate and policy for a sustainable and inclusive future (Divided Nations, Oxford

University Press, 2013, google books)

The 20th century was characterized by at least four terrible global tragedies. Two brutal world wars, a global

pandemic, and a worldwide depression affected almost everyone on the planet. In response to these and other crises the United

Nations (UN), Bretton Woods (the World

Bank and I nternational M onetary F und), and other international institutions

were created which aimed to ensure that humanity never faced crises on the same scale again. These

institutions have enjoyed some success. After all, we are yet to witness another global conflict despite decades of Cold War tension

between competing superpowers. Until 2008, modern-day recessions had not come close to the deep worldwide contraction created by the

Great Depression, for which the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank can claim some credit. The World Health Organization

(WHO) and other agencies may also take pride in having overcome polio, smallpox, and a number of other devastating communicable diseases

and preventing a significant global pandemic despite increasing connectivity and population density. The

future, however, will be

unlike the past. We face a new set of challenges. The biggest of these is that our capacity to manage global

issues has not kept pace with the growth in their complexity and danger. Global institutions which may

have had some success in the 20th century are now unfit for purpose. The repurposing of global

governance to meet the new challenges is a vital and massive undertaking. Responsibility for this revolution lies not just with

the global governance organizations themselves, or indeed with national governments. Nations are divided and cannot agree a

common approach, and within the leading nations there is no consensus or leadership on critical global

issues. The continued failure to resolve the financial crisis which started in 2007, the impasse in climate and

environment negotiations at the Rio+20 conference in 2012 and the Durban conference in 2011, as well as the stymied 'development

round’ of trade negotiations initiated in Doha in 2001 should be a wake-up call to us all. Global governance is at a

crossroads and appears

incapable of overcoming the current gridlock in the most significant global

negotiations. The number of countries involved in negotiations (close to 200 now) and the complexity of the

issues and their interconnectedness have grown rapidly, as has the effect ofinstant media and other pressures on politicians. These

and other factors have paralysed progress, so the prospect of resolving critical global challenges appears

ever more distant. We have reached a fork in the road. New solutions must be found. Resolving questions of global governance urgently

requires an invigorated national and global debate. This necessitates the involvement of ordinary citizens everywhere. For without the

engagement and support of us all, reform efforts are bound to fail. Structural

changes in the world have led to

fundamental shifts in the nature of the challenges and their potential for resolution. In this book I select five key

challenges for this century—climate change, cybersecurity, pandemics, migration, and finance—to illustrate the need for fundamental reform

ofglobal governance. I am not suggesting that these issues are completely new. It is the radical change in the nature of these challenges and the

complexity and potential severity of their impact that defines them as 21st-century challenges. The

UN, WHO, IMF, World Trade

Organization (WTO), and other institutions charged with global governance have undertaken reform at a painfully

slow pace. The growing disconnect between the need for urgent collective decision making to meet

21st-century challenges and the evolutionary progress in institutional capability has led to a yawning

governance gap.

Cooperation overwhelmingly fails

Krisch 14, The Decay of Consent: International Law in an Age of Global Public Goods Nico Krisch ICREA

Research Professor Institut Barcelona d’Estudis Internacionals,

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2335938

Interdependence. The trajectory of international law found in the present study is markedly different, and it reflects the fact that greater

needs for cooperation – obvious in all three issue areas under analysis – are not always, or not even typically , satisfied by

international law. It highlights Miles Kahler’s observation that legalization ‘is a complex and varied mosaic rather

than a universal and irreversible trend’.229 But it also suggests that international law faces particular

limitations when confronted with highly intractable public goods problems . In that it seems to confirm the

views – of many economists and lawyers alike – that the

classical international legal order, with its emphasis on

consent, is ill-equipped to deal with such problems . Instead of being transformed towards nonconsensualism, as expected

by many, international

law is surrounded and sidelined by alternative regulatory structures

minilateral, informal kind, and often with hierarchical elements.

of a unilateral,

2NC

Add-On

Multiple barriers mean bioterror is extremely unlikely

Schneidmiller, Global Security Newswire, 1-13-09 (Chris, “Experts Debate Threat of Nuclear,

Biological Terrorism,” http://www.globalsecuritynewswire.org/gsn/nw_20090113_7105.php)

Panel moderator Benjamin Friedman, a research fellow at the Cato Institute, said academic and governmental discussions of acts of nuclear or biological terrorism have tended to focus on

"worst-case assumptions about terrorists' ability to use these weapons to kill us." There is need for consideration for what is probable rather than simply what is possible, he said. Friedman

took issue with the finding late last year of an experts' report that an act of WMD terrorism would "more likely than not" occur in the next half decade unless the international community

takes greater action. "I would say that the report, if you read it, actually offers no analysis to justify that claim, which seems to have been made to change policy by generating alarm in

headlines." One panel speaker offered a partial rebuttal to Mueller's presentation. Jim Walsh, principal research scientist for the Security Studies Program at the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology, said he agreed that nations would almost certainly not give a nuclear weapon to a nonstate group, that most terrorist organizations have no interest in seeking out the bomb, and

that it would be difficult to build a weapon or use one that has been stolen. However, he disputed Mueller's assertion that nations can be trusted to secure their atomic weapons and

materials. "I don't think the historical record shows that at all," Walsh said. Black-market networks such as the organization once operated by former top Pakistani nuclear scientist Abdul

Qadeer Khan remain a problem and should not be assumed to be easily defeated by international intelligence services, Walsh said (see GSN, Jan. 13). It is also reasonable to worry about

extremists gaining access to nuclear blueprints or poorly secured stocks of highly enriched uranium, he said. "I worry about al-Qaeda 4.0, kids in Europe who go to good schools 20 years from

now. Or types of terrorists we don't even imagine," Walsh said. Greater consideration must be given to exactly how much risk is tolerable and what actions must be taken to reduce the threat,

he added. "For all the alarmism, we haven't done that much about the problem," Walsh said. "We've done a lot in the name of nuclear terrorism, the attack on Iraq, these other things, but we

have moved ever so modestly to lock down nuclear materials." Biological Terrorism Another two analysts offered a similar debate on the potential for terrorists to carry out an attack using

Leitenberg, a senior research scholar at the Center for International and

Security Studies at the University of Maryland, played down the threat in comparison to other health risks.