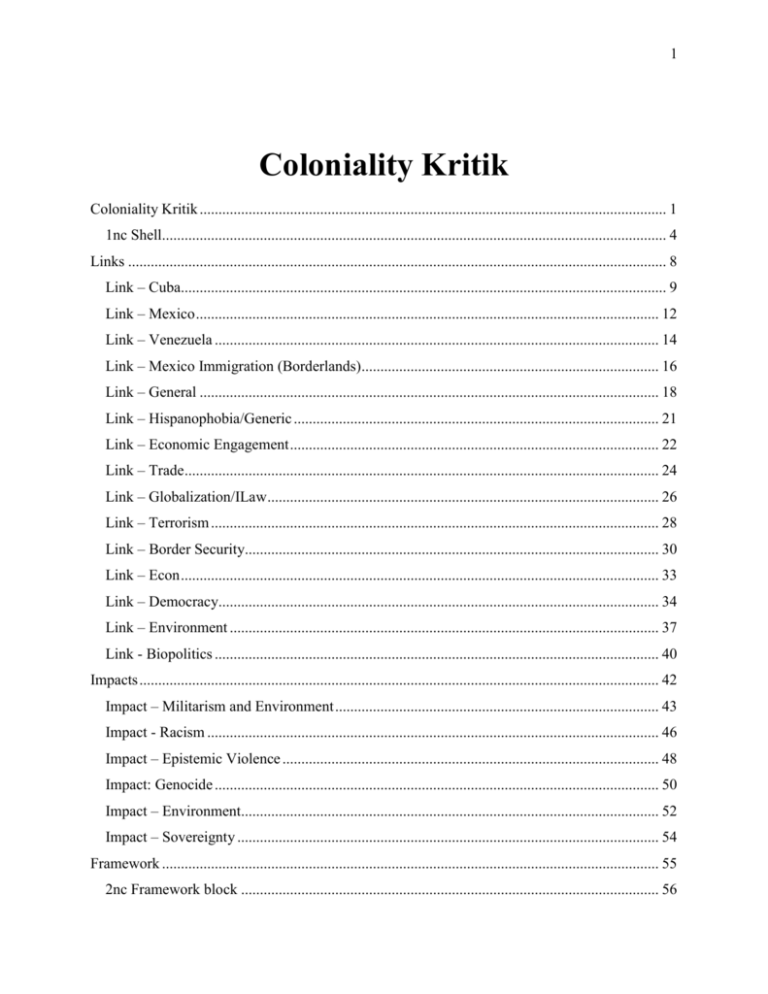

Coloniality Kritik

advertisement