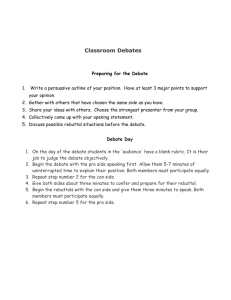

Debate handout

advertisement

Debate Jargon 1. Resolution: topic of debate Example: uniforms in school. 2. Position: a personal viewpoint or opinion. Example: I think uniforms in school would benefit students. 3. Motion or proposition: a suggestion or proposal. Example: I make a motion to require uniforms in school. 4. Pro: in favor of a motion. 5. Con: against a motion. 6. Affirmative Side (Proposition): makes and supports a motion. I represent the proposition and support the motion to have uniforms in school. 7. Negative Side (Opposition): opposes the motion. I represent the opposition and oppose the motion to have uniforms in school. 8. Argument: oral disagreement. 9. Constructive speech: position is presented and supported. Examples: My is name is Mrs. Fava and I represent the proposition. I make a motion to require uniforms in school… 10. Flowing: taking notes during the debate. 11. Rebuttal: response to opposing position. Example: My opponent says that uniforms save money, but I disagree. Uniforms actually increase a student’s clothes budget because parents have to buy uniforms and afterschool clothes. 12. Refutation: rebuttal strategy for disproving the opposing view. Example: While uniforms may create order, the more important issue is that they take away individual expression. 13. Discrediting: rebuttal strategy to make someone or something look bad. Example: My opponent may have good intentions, but she doesn’t understand what is at stake. As a teacher, she is more concerned with order in her classroom than the needs of students and parents. WHAT DOES A FORMAL DEBATE LOOK LIKE? DO… Come prepared to support your position. Make sure you understand the opposing position and how to refute it. Listen respectfully and silently when your opponent is speaking. Only speak during your turn or if your opponent gives you permission. Take notes throughout the debate so that you can address the specific issues raised by your opponent. Use formal language; sound educated and informed. DON’T… Expect to wing it. Do your research and time your argument to make sure you have enough material. Forget to prepare a strong rebuttal. Stating your own position is only half of the battle. Interrupt your opponent’s constructive speech; if you stand to speak and your opponent says, “No thank you,” sit down respectfully. Fail to take notes. Without written cues, it is difficult to make the most of your limited time in a debate forum. Use slang or sloppy speech. 2|Page INSTRUCTIONS: Objective: Collaborate with panel members to prepare an argument for a given topic and position. Topic: The school budget can only allow for physical education or music education (this includes team sports, band, and chorus). Which would you cut? Steps: Meet with panel: 1. Meet with your panel members and select a representative to meet with other panel’s representative. 2. Representatives will flip a coin to decide who gets to choose the position. Research: 3. Read through articles, highlighting words or sentences to support your position and refute the opposing view. 4. Write down three to four reasons to support your position. Make sure you can provide details from the articles to support your reasons. 5. Write down several points the opposition might make. Meeting again with panel: 6. Share your reasons and some points the opposition might make. 7. Assign each group member a reason to develop and one opposing point to counter or refute. Prepare your constructive speech and rebuttal: 8. Each group member will prepare the following: 9. Constructive speech: his or her reason and details (one minute in length). 10. Rebuttal: his or her counterpoint to an opposing point (one minute in length). Meet with panel for feedback on your argument: 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. Meet with panel to get feedback: Is your reason clearly stated? Do details support reason? Are supporting details well-developed? Is language formal and concise? Have you used appropriate starters such “According to Smith…” and “In Ashe’s article…”? Plagiarism is unacceptable. Give credit to the source! Revise: 17. Final preparation: make suggested revisions to your argument. 18. Time your constructive speeches and rebuttals. Final meeting: 19. Give feedback about delivery. 20. Present! 3|Page DEBATE RUBRIC (30 points) All panel debate members will be assessed on the following rubric: (5) Focus: Reason is clearly stated and supported by all details. (10) Content: Well-developed details are provided using primary sources and own ideas. (5) Organization: Appropriate starter phrases such as “According to the author of…” or “My opponent may say…” (5) Style: Expression is clear, concise, and formal. (5) Conventions: Speech is delivered with volume and clarity. Respect is given to other speakers. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Revision Checklist Editing Checklist Do you have any misspelled words? Have you checked end punctuation? Do you have the necessary commas and semicolons? Do all of your possessive words and contractions have apostrophes? Did you capitalize proper nouns, the beginning word of each sentence and the pronoun “I”? Is there proper heading and title included? Have you formatted the outline properly? Is your position clearly stated? Are two distinct reasons provided? Do details support reason? Are supporting details well-developed? Is the opposing view summarized? Have you refuted each opposing point? Is language formal and concise? 4|Page MODEL Name Period Date Resolution: Teacher’s Salaries Teachers’ salaries need to be increased. Reason 1: Teachers work many hours to plan instruction, grade papers, and communicate with parents. a. It takes many hours to plan organized lessons. For every lesson, teachers need to identify learning goals, prepare materials for instruction and practice, and plan assessments to measure student progress. b. Grading essays takes many hours as well; the average essay takes four minutes to grade. An average of 130 students x 4 minutes equals 8.6 hours. That is just one assignment. c. Teachers need to communicate with parents and often spend time each day emailing, phoning, and meeting with parents. In addition, teachers take time to post grades, assignments, and update their web pages so that parents can stay informed. d. If you were to include all of these additional hours for planning, grading, and parent contact, teachers work many hours in addition to 7:30 to 3:00 every day, and should be compensated for all of this effort. Reason 2: Teachers provide a valuable service to society. e. Teachers build young minds and give students the skills they need to prepare for the future. f. Teachers build character and show students how to contribute to a community. g. Teachers often provide emotional support for troubled students when no one else does. h. Athletes and actors are paid quite a bit for their work, but do they make the contribution to society that a teacher does? Rebuttal: My opponent might say that teachers have off all summer, work shorter hours than most other professionals, and earn a wage appropriate to their level of education and expertise. i. While teachers are officially off all summer, many teachers do a lot of planning and preparation during this time. j. Although teachers officially work from 7:30 to 3:00, the unofficial time spent on grading, planning, and mentoring students is much greater. k. Teachers do not earn a wage appropriate for their education and expertise. Most teachers have a Masters, so they went to school for at least six years. Many people in business with much less education can make double what a teacher earns. The Benefits of Music Education By Laura Lewis Brown Whether your child is the next Beyonce or more likely to sing her solos in the shower, she is bound to benefit from some form of music education. Research shows that learning the do-re-mis can help children excel in ways beyond the basic ABCs. More Than Just Music Research has found that learning music facilitates learning other subjects and enhances skills that children inevitably use in other areas. “A music-rich experience for children of singing, listening and moving is really bringing a very serious benefit to children as they progress into more formal learning,” says Mary Luehrisen, executive director of the National Association of Music Merchants (NAMM) Foundation, a not-for-profit association that promotes the benefits of making music. Making music involves more than the voice or fingers playing an instrument; a child learning about music has to tap into multiple skill sets, often simultaneously. For instance, people use their ears and eyes, as well as large and small muscles, says Kenneth Guilmartin, cofounder of Music Together, an early childhood music development program for infants through kindergarteners that involves parents or caregivers in the classes. “Music learning supports all learning. Not that Mozart makes you smarter, but it’s a very integrating, stimulating pastime or activity,” Guilmartin says. Language Development “When you look at children ages two to nine, one of the breakthroughs in that area is music’s benefit for language development, which is so important at that stage,” says Luehrisen. While children come into the world ready to decode sounds and words, music education helps enhance those natural abilities. “Growing up in a musically rich environment is often advantageous for children’s language development,” she says. But Luehrisen adds that those inborn capacities need to be “reinforced, practiced, celebrated,” which can be done at home or in a more formal music education setting. According to the Children’s Music Workshop, the effect of music education on language development can be seen in the brain. “Recent studies have clearly indicated that musical training physically develops the part of the left side of the brain known to be involved with processing language, and can actually wire the brain’s circuits in specific ways. Linking familiar songs to new information can also help imprint information on young minds,” the group claims. This relationship between music and language development is also socially advantageous to young children. “The development of language over time tends to enhance parts of the brain that help process music,” says Dr. Kyle Pruett, clinical professor of child psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine and a practicing musician. “Language competence is at the root of social competence. Musical experience strengthens the capacity to be verbally competent.” Increased IQ A study by E. Glenn Schellenberg at the University of Toronto at Mississauga, as published in a 2004 issue of Psychological Science, found a small increase in the IQs of six-year-olds who were given weekly voice and piano lessons. Schellenberg provided nine months of piano and voice lessons to a dozen six-year-olds, drama lessons (to see if exposure to arts in general versus just music had an effect) to a second group of six-yearolds, and no lessons to a third group. The children’s IQs were tested before entering the first grade, then again before entering the second grade. Surprisingly, the children who were given music lessons over the school year tested on average three IQ points higher than the other groups. The drama group didn’t have the same increase in IQ, but did experience increased social behavior benefits not seen in the music-only group. The Brain Works Harder Research indicates the brain of a musician, even a young one, works differently than that of a nonmusician. “There’s some good neuroscience research that children involved in music have larger growth of neural activity than people not in music training. When you’re a musician and you’re playing an instrument, you have to be using more of your brain,” says Dr. Eric Rasmussen, chair of the Early Childhood Music Department at the Peabody Preparatory of The Johns Hopkins University, where he teaches a specialized music curriculum for children aged two months to nine years. In fact, a study led by Ellen Winner, professor of psychology at Boston College, and Gottfried Schlaug, professor of neurology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, found changes in the brain images of children who underwent 15 months of weekly music instruction and practice. The students in the study who received music instruction had improved sound discrimination and fine motor tasks, and brain imaging showed changes to the networks in the brain associated with those abilities, according to the Dana Foundation, a private philanthropic organization that supports brain research. Spatial-Temporal Skills Research has also found a causal link between music and spatial intelligence, which means that understanding music can help children visualize various elements that should go together, like they would do when solving a math problem. “We have some pretty good data that music instruction does reliably improve spatial-temporal skills in children over time,” explains Pruett, who helped found the Performing Arts Medicine Association. These skills come into play in solving multistep problems one would encounter in architecture, engineering, math, art, gaming, and especially working with computers. Improved Test Scores A study published in 2007 by Christopher Johnson, professor of music education and music therapy at the University of Kansas, revealed that students in elementary schools with superior music education programs scored around 22 percent higher in English and 20 percent higher in math scores on standardized tests, compared to schools with low-quality music programs, regardless of socioeconomic disparities among the schools or school districts. Johnson compares the concentration that music training requires to the focus needed to perform well on a standardized test. Aside from test score results, Johnson’s study highlights the positive effects that a quality music education can have on a young child’s success. Luehrisen explains this psychological phenomenon in two sentences: “Schools that have rigorous programs and high-quality music and arts teachers probably have high-quality teachers in other areas. If you have an environment where there are a lot of people doing creative, smart, great things, joyful things, even people who aren’t doing that have a tendency to go up and do better.” And it doesn’t end there: along with better performance results on concentration-based tasks, music training can help with basic memory recall. “Formal training in music is also associated with other cognitive strengths such as verbal recall proficiency,” Pruett says. “People who have had formal musical training tend to be pretty good at remembering verbal information stored in memory.” Being Musical Music can improve your child’ abilities in learning and other nonmusic tasks, but it’s important to understand that music does not make one smarter. As Pruett explains, the many intrinsic benefits to music education include being disciplined, learning a skill, being part of the music world, managing performance, being part of something you can be proud of, and even struggling with a less than perfect teacher. “It’s important not to oversell how smart music can make you,” Pruett says. “Music makes your kid interesting and happy, and smart will come later. It enriches his or her appetite for things that bring you pleasure and for the friends you meet.” While parents may hope that enrolling their child in a music program will make her a better student, the primary reasons to provide your child with a musical education should be to help them become more musical, to appreciate all aspects of music, and to respect the process of learning an instrument or learning to sing, which is valuable on its own merit. “There is a massive benefit from being musical that we don’t understand, but it’s individual. Music is for music’s sake,” Rasmussen says. “The benefit of music education for me is about being musical. It gives you have a better understanding of yourself. The horizons are higher when you are involved in music,” he adds. “Your understanding of art and the world, and how you can think and express yourself, are enhanced.” Physical Education is Critical to a Complete Education Source: National Association for Sport and Physical Education Overview Physical education plays a critical role in educating the whole student. Research supports the importance of movement in educating both mind and body. Physical education contributes directly to development of physical competence and fitness. It also helps students to make informed choices and understand the value of leading a physically active lifestyle. The benefits of physical education can affect both academic learning and physical activity patterns of students. The healthy, physically active student is more likely to be academically motivated, alert, and successful. In the preschool and primary years, active play may be positively related to motor abilities and cognitive development. As children grow older and enter adolescence, physical activity may enhance the development of a positive self-concept as well as the ability to pursue intellectual, social and emotional challenges. Throughout the school years, quality physical education can promote social, cooperative and problem solving competencies. Quality physical education programs in our nation’s schools are essential in developing motor skills, physical fitness and understanding of concepts that foster lifelong healthy lifestyles. Physical Benefits Physical education is unique to the school curriculum as the only program that provides students with opportunities to learn motor skills, develop fitness and gain understanding about physical activity. Physical benefits gained from physical activity include: disease prevention, safety and injury avoidance, decreased morbidity and premature mortality, and increased mental health. The physical education program is the place where students learn about all of the benefits gained from being physically active as well as the skills and knowledge to incorporate safe, satisfying physical activity into their lives. Middle School The middle school student is ready to experience a wide variety of applications of fundamental movements, including traditional sports, adventure activities (e.g., rock climbing, ropes, kayak, skiing), and lifetime or leisure-oriented activities (e.g., roller-blading, biking, dance). It is during this period when students are capable of refining, combining and applying a variety of sport-related and lifetime skills. Students may explore afterschool opportunities for specialized or/and competitive physical activity programs. Rapid growth during the pre-adolescent years may affect students’ interests, choices, and activity patterns. Therefore physical education programs offer a variety of activities to meet and expand student interests. Fitness development becomes more systematic. Students develop specific fitness components, set goals and assess personal fitness levels. Cognitive Benefits Children learn through a variety of modalities (e.g., visual, auditory, tactile, physical). Teaching academic concepts through the physical modality may nurture children’s kinesthetic intelligence. Academic constructs have greater meaning for children when they are taught across the three realms of learning, including the cognitive, affective and psychomotor domains. Greater depth and relevance can be achieved when the subject matter constructs are related to each domain of learning. Research has demonstrated that children engaged in daily physical education show superior motor fitness, academic performance, and attitude towards school versus their counterparts who did not participate in daily physical education. Physical education learning experiences also offer a unique opportunity for problem solving, self-expression, socialization, and conflict resolution. Middle School Middle school students are intensely curious, prefer active to passive learning, and definitely favor interaction with peers during learning activities. The early adolescent exhibits a strong willingness to learn things they consider useful. They enjoy using skills to solve real life problems. Quality physical education programs provide a medium through which middle school students can refine and expand upon their physical repertoire of skills. It has been shown that students miss fewer days of school because of illness and exhibit greater academic achievement because of the physical vitality gained in physical education. Affective Benefits Physical competence builds self-esteem. Quality physical education programs enhance the development of both competence and confidence in performing motor skills. Attitudes, habits, and perceptions are critical prerequisites for persistent participation in physical activity. Appropriate levels of health-related fitness enhance feelings of well being and efficacy. Middle School Quality middle school physical education programs provide students unique opportunities for demonstrating leadership, socialization, and goal setting skills. Involvement in physical activity has shown a consistent relationship with mood, self-esteem, and other indices of psychological well-being in early adolescence. Student preferences become more specialized at this age and the preference influences students’ motivation to continue in physical activities. A youngster’s feelings of perceived competence also affects future participation and selfesteem. Despite the physiological changes that occur at this age, students are generally willing to work cooperatively toward common goals because the desire for peer group acceptance is strong. Risk taking is attractive and students accept the challenge of setting and achieving personal goals. Physical education programs have a unique opportunity to provide learning experiences that enhance middle school students’ self-esteem. Physical Activity Improves the Quality of Life Regular physical activity improves functional status and limits disability during the middle and later adult years. Physical activity contributes to quality of life, psychological health, and the ability to meet physical work demands. Physical education can serve as a vehicle for helping students to develop the knowledge, attitudes, motor skills, behavioral skills, and confidence needed to adopt and maintain physically active lifestyles. The outcomes of a quality physical education program include the development of students’ physical competence, health-related fitness, self-esteem, and overall enjoyment of physical activity. These outcomes enable students to make informed decisions and choices about leading a physically active lifestyle. In early years children derive pleasure from movement sensations and experience challenge and joy as they sense a growing competence in their movement ability. Evidence suggests that the level of participation, the degree of skill, and the number of activities mastered as a child directly influences the extent to which children will continue to participate in physical activity as an adult. In early adolescence participation in physical activity provides important opportunities for challenge, social interaction, group membership, as well as opportunities for continued personal growth in physical skill. Participation for high school students continues to provide enjoyment and challenge as young people express preferences for activities that meet their specific interests. A comprehensive, well-implemented physical education program is an essential component to the total education of students. Physical education prepares students to maintain healthy, active lifestyles and engage in enjoyable, meaningful leisure-time.