E4426 V2

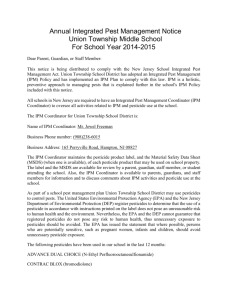

advertisement