here

advertisement

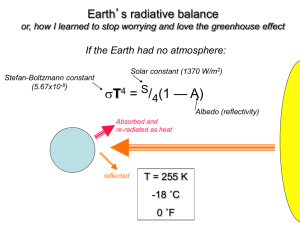

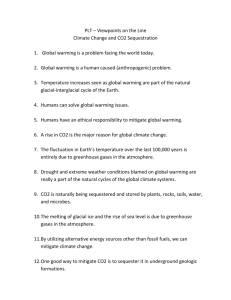

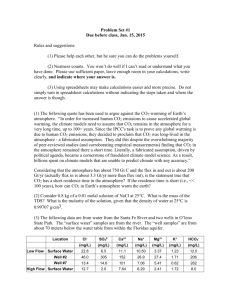

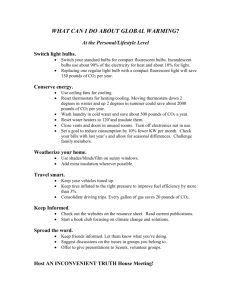

An open letter to my family To three generations of Goodhew, Smiths and Shiells I want to pass on some thoughts about all our futures. I’m sorry if this seems gloomy, but I believe that the issues facing us are very serious. This is probably a bad time to be saying this, but there is never a good time for bad news. Firstly my generation must acknowledge that we had it easy: No world wars, stable employment, free university, good pensions and (in the West) incredible technological developments. Most of you are likely to belong to the first two generations to have a lower quality of life than their parents, and the last few generations (including mine) should apologise for their lack of consideration and foresight. Secondly, my reading around climate change, population and economics leads me to believe that there are some certainties (almost facts) about the future. Among these are: 1. World population will rise from 7 billion to 9 billion within a generation or two, whatever we do. It will rise further if we do not make real efforts to reduce the birth rate. The only ways in which population might fall are terrible: large wars; mass starvation; epidemics. 2. The current population of the world is using earth’s resources at a rate larger than they can be replaced. Some calculations say by about one-and-a-half times, the more pessimistic say by three times the sustainable rate. By resources I mean non-renewable energy supplies and, for example, food, trees and clean water. And of course some things are totally irreplaceable: rare metals are a good example. We might re-use them but we cannot make any more. This is one of the reasons for my next point. 3. Growth cannot continue indefinitely. This applies to everything: GDP; mineral resources; food; population, house prices. As a trivial example consider your waistline: If this was 30 inches ( 75cm) in your teens and it grew at only 1% per year (less than inflation!) you would have a waist measurement of 50 inches (127cm) in your sixties and if you were to live to over 100 it would rise to 80 inches (over 2 metres). It’s the same with our use of any resource such as land or oil or trees. It cannot go on growing indefinitely for hundreds of years. We must learn to live without growth. We can still improve our quality of life, but not by having more of anything. 4. Climate change is happening. Average temperatures are rising, sea level is rising and as a result many (indeed most) areas of the planet will experience changed conditions. It matters little exactly why these changes are occurring, nor exactly how large the changes will be: They are irreversible for hundreds of years and will affect every continent. 5. The main consequences of climate change will be flooding of low land resulting in the displacement of populations, acidification of the sea leading to loss of species (including food species), the relocation of arid and fertile areas (deserts and forests will move north or south) and more frequent bouts of extreme weather. All this is now inevitable, as many thousands of scientists agree. Almost all scientists concur that a large part of the change is driven by carbon dioxide (CO2) produced by man’s activities. But it doesn’t really matter if they are wrong, because the facts are that we are warming and the ice is melting. Some of the questions we cannot fully answer are: How bad will it be where we are? When will governments wake up to the issue and start doing something? How will events elsewhere on the planet affect us? From here on I am speculating, so these are my considered opinions, not scientific fact. a. How bad will it be where we are? In the short term (fifty to a hundred years) it won’t be much of a direct problem for us in the UK, except for low-lying areas. We can withstand severe storms and periods of drought, although we need to ensure that we collect and retain enough water to use in dry periods. Indirectly we are likely to experience rising energy prices, a lower standard of living, difficulties with importing food (both because it is needed elsewhere and because we should not emit so much CO2 bringing it in) and so on. While this is happening we can of course try to do something about it: We can build flood defences, wind farms and other renewable energy sources, and we can use our energy more efficiently, but only if we agree to a lower standard of living. b. When will governments wake up to the issue and start doing something? I fear that governments everywhere will be slow to react, for different reasons: In the West it will be difficult for a government to persuade its electorate to cut its standard of living while the weather and flooding are having only a small impact locally. CO2 in the atmosphere lasts hundreds of years, so changes now will only bring benefits in the long term, and we cannot stop the first couple of degrees of global warming (and probably the third). Governments are not very good at spending for the long term (i.e. beyond their period in office). Governments in developing countries such as India, China and Indonesia (who emit a large fraction of the world’s CO2) will find it hard to tell their population that they are going to prevent them ever reaching Western levels of affluence. Governments in really poor countries (like much of Africa) will argue that they can’t make much difference anyway – they emit only a small part of the world’s CO2. (Although they are also in many cases responsible for deforestation.) Capitalism, which is now dominant across the world, means that we cannot expect a company to act altruistically if this puts it at a competitive disadvantage. Only governments can insist on a long-term approach with short-term costs. There will not be agreement among a majority of world governments until conditions for each of them are so stark that the need for action is obvious. In my view, this will be so late that tipping points such as the melting of Greenland ice and major Antarctic glaciers will be unstoppable, leading to several metres of rise in sea level. c. How will events elsewhere on the planet affect us? We will not be able to ignore events elsewhere: You could argue that the UK could protect itself. It could divert a few percent of GDP to flood defences, reservoirs, wind farms and tidal barrages (and, yes, nuclear power stations). It could reconfigure its agriculture to become self-sufficient in food (more boring, but sufficient) until and unless a potato blight or wheat disease swept the country (think elm disease and ash die-back). It could close its borders against immigration (and anyway would have to vastly reduce air travel), until populations more desperate than us reach the Channel and decide (rightly or wrongly) that life is better over here. If life in other parts of the world (for example Africa, distant parts of Asia or even Spain) became intolerable I do not believe that we could pull up the drawbridge and carry on independently. So the impact of climate change on the rest of the world is eventually an impact on us, however sensible we will have been over the next few decades. What could be done? There are two main requirements for long term survival: One is to reduce the atmospheric CO2 and thus slow global warming, and eventually – after several hundred years – reduce it; the other is to reduce world population to a sustainable level (maybe 5 billion or less – 1 billion would be much better). The first is possible, mainly by switching to renewable energy, using less energy and cutting down fewer trees. However there is little sign of this happening fast enough. The second is improbable except by the sort of disasters I described above. It may happen, but no government is addressing it – even the famous one-child policy in China has done nothing to reduce population, only a little to slow its growth. And they have almost abandoned it! Then there is geoengineering: One possibility is seeding the upper atmosphere with sulphur dioxide to increase the reflection of sunlight. OK, it might work, but we cannot predict the knock-on consequences of putting a new ingredient into the atmosphere, and we would have to continue doing it for ever. If we stopped, temperatures would rise rapidly, because of the high CO2 level in the atmosphere. There is much talk of carbon capture and storage (CCS). This is being tried, but no large-scale plant is yet in operation at a power station and, even if it works well, it can only prevent more CO2 being emitted from fossil fuelled power stations and cannot prevent the existing CO2, which will be around for a thousand years, from warming us. And it would add considerably to the price of electricity. Where will it all end? I do not believe that the human race will die out. But I do believe that there will be widespread disasters which will reduce the population dramatically. This would solve, or postpone for a long time, the main problems and the earth could recover in some hundreds or thousands of years. However the disasters would be horrible to live through (or die in). They could include starvation, civil war and epidemics in densely populated areas, and simply starvation in sparsely populated areas. There could be nuclear war if the fight for land or water becomes too desperate. Note how easily and quickly society has broken down recently in Syria and Ukraine, without any of these major pressures! I would not want to be around to experience this. Why should you not believe these common arguments? “The UK is responsible for a tiny fraction of the world’s CO2 emissions. Even if we reduced ours to zero the emissions from China and India (and the USA?) would still carry on, so we are wasting our time doing anything.” This is technically true, but imagine the likelihood of China and India taking the necessary tough steps if the Western world does not. We should be leading by example, not burying our heads in the sand. And, as I wrote above, the rest of the world’s problems would soon become our problem. “We can simply build defences against flooding, and then we’ll be all right – in fact if our local climate gets a bit warmer and wetter we will be able to grow more food.” Yes, but see above, and, if the ice on Greenland and Antarctica starts to melt in a big way (past the “tipping point”) we will have an eventual sea level rise of 65m, which would wipe out whole countries. Our population density would also rise dramatically if we all had to live on a smaller island. So what do I think you should do? At one level this is very easy – save energy, eat local food but no meat, don’t fly anywhere. Vote for anyone who opposes growth and who does not hide the fact that your standard of living is going to fall. Beyond this it gets very difficult. If I were twenty I would seriously consider not having children. This is an awful thing to say to a girl or woman but it is not just a matter of reducing the population – your gesture will make little difference. It is just that I would not want to see children born early in this century, who could reasonably expect to live into the next century, having to live through the hardship and turmoil which I think is coming. Their quality of life is likely to be very poor. This is not like wartime – wars end. This is for the whole of your lifetime, your children’s lifetime and their children’s lifetime – and more. I’m sorry to be so pessimistic. You will find others who don’t agree with my long-term conclusions; who think that man is clever enough to devise a way out. Nigel Lawson is one of these and has written a book about it. However I find myself more persuaded by the books I have listed below. I have copies of all of them if you want to read up on the subject. Good luck! Peter (as husband, brother, father, uncle and grandfather); March 2014 Some reading (only the first requires much science or maths, but it does have most of the facts): • Introduction to Modern Climate Change: Andrew Dessler • Prosperity without Growth: Tim Jackson • The End of Growth: Richard Heinberg • The Hot Topic: Gabrielle Walker & David King • Requiem for a Species: Clive Hamilton • The Great Disruption: Paul Gilding and, if you want the counter-argument: An Appeal to Reason - A Cool Look at Global Warming: Nigel Lawson