Korean Roads Past and Present

advertisement

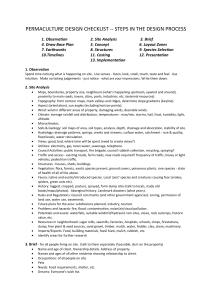

PAST KOREAN ROADS PAST AND PRESENT. BY W. W. TAYLOR. The subject of this article was suggested to the minds of the Officers of this Society by a motor trip which the writer made during the late winter of 1923, which is probably the longest continuous motor trip made in this country up to that time. Before beginning the narration of that trip it is the writer’s intention to tell some of the condition of the roads in the past and the method of travel thereon. though to many present this will be recalling old trails, but pioneers are never averse to going over the trails of the past cosily ensconced in an easy chain My first trip to Korea was made in the spring of 1898 and while I had learned from my father’s previous trip that Korea was in the Orient and an independent country, as much could not be said for the knowledge of my boy friends and some of their elders. For years after my arrival I received letters addressed, Korea, Africa: Korea, India : Korea, China: and Korea, Japan: and in some cases it was carefully designated an island. Twenty odd days across the Pacific in a boat little larger, if any, than the larger ferry steamers plying between Shimonoseki and Fusan these days, landed our party of 13 rough-neck miners in Nagasaki, then a leading port of Japan. Here we were kept 13 days watching the kite flying, which I as a boy greatly enjoyed, before we were able to get a passage on a small Russian steamer to Chefoo and then on to Chemulpo. Our first sight of the boundless horizon of mud fiats of that port was not inspiring but our interest was soon awakened by the curious white clothes of the natives and the enormous loads carried by the coolies on the bund, and it was this latter that particularly impressed the miners who had swung an eight-pound hammer most of their lives and appreciated physical prowess. I don’t recollect whether they gave us anything to eat at Stewards or not, for that was the leading hotel of the country in those days and for a long time after, for we were herded[page 36] on a small coasting steamer and memory of feeds here fails me completely for a long time. We ran along the coast hugging the shore, always in sight of mud banks, the Captain ever on the alert to run to the sheltering-lee of an island at the first sign of danger, as he evidently had very little faith in the staunchness of the wooden hulk he commanded, and evidently felt the responsibility for having our party aboard, for we were the largest party of foreigners he had ever undertaken to transport to Pyengyang at one time. Yes, Pyengyang was our destination, but we never reached it on that steamer for we missed a tide when we got up a way and our good skipper decided to get us off as soon as possible, and with this end in view dropped us off somewhere between Chinnampo and Pyengyang. We were soon huddled in san- pans and told to keep going, which was a mighty hard thing do to against the tide. Some of the Koreans fell exhausted from their efforts at the oars and it was not until some years later that we discovered that this was a polite way of letting us understand we could take a spell. We probably showed up pretty well for I remember we had heard of the General Sherman, and the fate of her loomed up before our imaginations and spurred us to heroic efforts. I suppose that many of you have tried your hand at the native oar and will predate our efforts against the swift tide, spurred on by our apprehensions. After about ten hours of this work many of us were ready to turn back but a good breakfast at Dr. Wells, place, which my father after a great deal of scouting had managred to find, we felt better and looked forward to our overland journey to the Unsan Mines, which was our destination. Don’t think patient listener or reader that I have drifted away from my subject for it is right here that I relate my first experience with the Korean road of the Kusik or old style, mounted at times on the back of a Korean pony, and at other times wallowing around in the mud of thawing paddy fields. I am not going to describe a Korean pony though he is rare enough these days to need description for recent comers, but will ask you to read Dr. Gale’s description in that fascinating[page 37] book “Korean Sketches.” Just read this and then draw on your imagination to picture the disgust and scorn on the faces of those six-foot Western miners when they saw what they had to ride, and compare them with the broncos of the ranch at home. Many swore that they would walk to the end of the earth before they would mount on top of the huge pack that the little creature was carrying, but after a few hours of plodding through sticky clay and stumbling over hidden boulders, up steep rocky passes and down the slippery other side with an endless vista of the same sort of country, even the most stubborn yielded and climbed aboard their mounts, and this weird procession of foreigners, with the Chinese cook, Beans, bringing up the rear, straggled along for three days. It is often said that transportation is civilization and if so, then Korea at that day was pretty far down the scale; for there was nothing from one end of the peninsula to the other that was worthy of the name of road. This might raise the question of what was then considered the main artery of the country, from Fusan to Seoul ana from Seoul to Wiju. Granted there was a route that was followed by the Chinese envoys who came yearly to collect tribute when Korea was a vassal state, and over which officials travelled to their posts, but wheeled carts never passed over them and the Chinese and Korean officials suspended on the stout shoulders of their chair coolies never felt the bumps or jolts. Many will remember the thrill of pride at the endurance and pluck of some missionary who had ridden all the way from Pyeng- yang to Seoul on a bicycle. Dr. McGill won everlasting and well-deserved fame by driving a light horse cart from Seoul to Wonsan, a distance of 500 li, or 160 miles. The writer made it by pony and considered it one of the hardest in Korea. The next time you are on your vacation trip to Wonsan Beach and passing through that gorgeous mountain scenery, look out of the window and catch glimpses of this old road at certain points where it touches the right-of-way, and you will get an idea of travel in the good old days, now gone forever thank the Lord. Don’t get mixed and mistake one of the new [page 38] Government roads, but if you see a washed out rocky sort of cow trail, that is the remains of an old road. Probably the first wheeled traffic to make a journey over the korean roads for any distance was the transport of the japanese army in their victorious march against china. Undoubtedly work was done on the roads at this time, but they were soon allowed to sink back into their primitive condition. If such was the condition of the main highway of the country, the condition of the small branches can be better imagined than described. The road over which we had travelled to unsan had been put in some shape to bring in mining machinery some two years before by my father when starting work at the mines, but the officials would not even keep it in repair, and in the lapse of two years it was back to its pristine beauty. A bull cart would undertake the adventure if well paid, but no date of arrival was set we had some very essential replacement to the mill sent up overland from seoul, paying an enormous figure. After two months two foreigners went after them and returned triumphantly after another month, and the mill hung up all the time. Most of the machinery for a long time was made in sections and transported on the faithful pony, or by cow back. In winter when the snow was on the ground, we were able to make use of the primitive korean sled. The preparation of this road, and the one from pakchun, was probably the first work done on roads except for military purposes, outside of the environs of cities or roads to tombs. Many times on the trip of the thirteen from pyengyang to unsan, all bands would have to lend a hand to pull a pony and its rider out of a bog, grabbing whatever was projecting. The next time your car runs off the road or you have to make a detour on account of a washed-cut road, think of the good times we old timers did not have. I now pass on to the second phase of my experience with korean roads, for after five years at the unsan mines i became restless and sought pastures new, and, as most of the searching was done over korean roads and from the back of a korean pony, there was some pretty rough going. The year THE REMAINS OF AN OLD ROAD (See page 38) BULL CART [page 39] 1904 saw the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese war and I signed up with the New York Herald as correspondent, and March of that year saw me getting better acquainted with travel in Korea for I made the trip from Seoul to Pyengyang and from Pyengyang to Wiju with Kuroki’s army. The Seoul to Pyengyang was 550 li by the long route, and 500 li by the short, and a similar distance to Wiju, the total being, as the mapoos (horse-drivers) would always agree after a most vociferous argument, 1000 li, or about 300 miles. During this period the Japanese army engineers had done some work on the road, but 120 li per day was good going, and I honestly believe there was no other animal in the world save the Korean pony that could have made this distance day after day under the conditions and with equal loads. The Japanese engineers did not attempt to keep up the repairs on this road, as they soon were busily engaged in building a new railroad from Pyengyang to Wiju, and from Pyengyang south, and had not yet in view the fine system now under construction. In 1904-5 and 6 I made many trips in the interests of the New York Herald, and prospecting trips on behalf of the Collbran Bostwick Mining Syndicate, and everywhere I went it was the same, appalling roads, lack of bridges, or only the most primitive makeshifts. I would like to describe some of the wonderfully fascinating scenery and glimpses of native life which compensated for the hardship, but I must get on. From Pyengyang across country to Wonsan, the 500 li was little more than a rough trail. A glance at the map will show you that this route takes one over the backbone ridge of Korea, and it is the great cost of tunnelling here that has kept the Japanese from making better progress on this important railroad line. At that time the country covered by that route was very sparsely settled with a few struggling farmers at intervals between the villages. At night the hill-sides glowed and blazed with the fires set by nomadic farmers to clear off the trees and shrubbery. As soon as the ground was cool they planted their crops of buckwheat and potatoes in this highly fertilized soil, did this for a year or two and then passed on to a new bit of hard wood forest and [page 40] laid waste to it, leaving the last place to the mercy of the torrential rains which, no longer held in check by the trees, swept away every vestige of soil. This sort of savage agriculture was practiced all through the north and, fostered by the lack of transportation, Korea lost huge tracts of valuable hard timber, and upset nature’s conservation of the rainfall In those days stopping places were widely separated, and in the mountains the mapoos’ (horse-drivers’) talk turned to robbers and tigers, both of which were by no means uncommon. When forced by necessity to travel by night, as I was, the scene became weirdly picturesque for we were lighted on our way by the yamen runners with blazing torches which shed showers of sparks, who with eerie cries to keep away the tigers and to bolster their courage, led us with a final crescendo of yells to the village where a new relay of torch bearers escorted us on to the next station, and so on through the night This stands out in vivid contrast to a trip over a good road in a motor car with a warm bath and comfortable hotel at the end, which it is possible to take anywhere now in this same vicinity. During: the war and two years afterwards I travelled this section North, East, South and West, and what I have written of the roads already holds true for all the rest, and the roads through the southern provinces, the granary of Korea, were in nowise different With the Korean policy of isolation and discouragement of travel to the outside world, it is not sur-prising that a lack of appreciation of the vital necessity of good internal communication should prevail, with a corresponding backwardness in all the other arts and sciences that have to do with the physical comfort and well-being of man. Before passing on to my motoring experiences in the country which were principally with that gallant friend of the pioneer, the Ford, I want to speak of the King’s Highway, probably the first real road constructed in Korea. This road, which leads out of the East Gate to the Nine Kings, Tombs, and to the two tombs of the late Emperor and Empress of Korea, was contracted for and built by Collbran and NEW’ ROAD OVER MOUNTAINOUS SECTION [page 41] Bostwick. It was laid out of generous width, and the bridges were of Oregon Pine. With only the most casual attention, just before some ceremonial, it remained in good condition for a long period, for the materials for constructing good roads are at hand nearly everywhere in Korea. It was lined with trees which were subjected to less vandalism than wayside trees usually suffer in Korea. Statistics are always uninteresting to the writer as well as the reader of the article, but as an article does not seem to be complete or impressive without them, I will insert some important ones, but will travel as lightly and as quickly as possible over this stage. Shortly after the Russo-Japanese War (1906) and when Japan commenced to exert her paramount position in Korea, we find that one of the first grants that was set aside out of the “Loan for Public Undertakings” was ¥1,500,000 with which to construct four roads, namely :一 From Chinnampo to Pyengyang, From Taikyu to Ya Nil Bay, via Kwangju, From Yonsankang to Mokpo, From Keun-Kang to Kunsan. As in Japan, roads in this country were planned so as to connect either the ports or large cities lying in the interior with the railroads. The survey for these four roads was made in 1906 and totalled 65 ri or 162½ miles, and they were 3 to 4 ken wide, that is 18 to 24 feet. Actual work on these roads was commenced in 1907 and during this year fifteen were completed. During this period preliminary surveys were made for seven other roads, the construction and completing of which were to serve as models and a stimulus for further work to be undertaken by the local government in the future. From 1906 to the end of 1912 the state highways constructed amounted to 320 ri in length, the expense of construction having been borne by the Central Government, while the local government had constructed and completed roads of all classes. During this period several methods as well as means were employed by the Japanese in construction[page 42] of these roads, and I will treat lightly on this subject before passing on. Shortly after the crushing of the Ilchinhoi (Anti-Japanese Association) with a view of employing thousands of these disarmed patroiots, Japan planned and constructed with this labour in 1909-1910 a road 39 ri long extending between South Chulla and South Kyong-Sang. Further roads on the East Coast between Chong-jin and Sungjin were also commenced in 1909. The four roads previously mentioned were completed in December 1909. Many of the roads constructed throughout Korea have been built by local labour, aided by subsidies from the Central Government Daring the period previously mentioned and up to 1912, which probably are the greatest years in Korea’s history as far as road construction is concerned, more roads were planned or completed than in any other periods After careful investigation the Government General adopted a plan of road construction amounting to 26,000 ri. The first part of this enormous plan or scheme, work on which was to commence in the fiscal year of 1911, covered a period of five years, and consisted of 23 roads measuring 580 ri at an estimated cost of ¥10,000,000. Table No. 1, attached hereto, will give an idea as to the roads actually completed up to the end of 1910. The cost and construction of these roads over a period of five years 1911-1915, is given in Table No. 2. Of these 23 roads, eleven were first and second class totalling 117 ri in length, but not more than 13% was completed, due to the floods, and the construction of the unfinished roads first mentioned and planned prior to the annexation, amounting to 8 ri. During this period the custom called ‘‘Pyuok,” which had long been in vogue but seldom used except when some official was to pass through the distict, was enforced, and much repair of roads between villages was accomplished. In this connection, while the labour was furnished by the village, the expense of bridge building and heavy cuts was borne by the special local expense fund During 1911 an ordinance by which roads divided into four classes was enacted. SHOWING CHARACTER OF COUNTRY OVER WHICH NEW ROADS PASS [page 43] First class, roads, 4 ken or over, running between Seoul and the Provincial Seats, Garrison Towns, Ports, Naval Stations, and Railway Centres. Second class roads of 3 ken or more, and usually connecting Provincial Government towns with Magistrate towns or to Railway Stations. Third class roads of 2 ken were determined by the Pro-vincial Government and approved by the Governor General. Fourth class roads were other than the above mentioned, and undertaken by the local officials of the district through which they were run. The maintenance of the roads was undertaken as follows : Those of the first and second class by the Government General, the third by the Provincial Government and the fourth by the Prefectural and District Magistracies. In addition to these roads a large programme for the im-provement and building of city roads in Seoul, Pyengyang, Fusan, Chunju and Haiju, was conceived and carried out. It has often been said, and this in the way of an adverse criticism, that Japan undertook and built this fine system of roads from a purely selfish military point of view ; but a study of the map and tables given will soon show the student of road construction that this is not entirely true and that large parts of these roads were constructed from a purely economic point of view. There is no doubt that many of these roads connect garrison towns with naval and military ports, but even so they have brought untold wealth and happiness to the people of these districts through which they traverse. The Korean of the old type is fast disappearing, and these roads and the fast transportation and communication made possible thereon, are gradually bringing all to a realization of the value of time besides allowing them to haul their products to market where they are able to get a fair price, taking back luxuries which they or their families never dreamed of in the old days. Korea was annexed to Japan, as previously mentioned, in August 1910. but before that she was a protectorate of[page 44] Japan for four years. Let us review briefly these nine years of Japan’s rule and its bearing on road construction. In this connection we should mention Count Terauchi’s administration covering the five years up to and including most of 1916, and it was during this period that Korea’s fine system of road building on a grand scale was planned ana largely carried out It has often been said that many of the roads and streets were planned by Count Terauchi by the simple and often sought method of taking a rule and drawing a straight line through the section the street or road was to pass. This undoubtedly was far-fetched, and we must give great credit to him, and the strength of will and power he exerted which gave us these roads where a weaker Governor-General would have failed utterly. There is no doubt that the natives suffered at times where roads passed through their land, or their labour was demanded, but in the writer’s mind they have been fully compensated by the increased value to land in their districts that these efforts have brought forth. In 1915 we find that the programme for road construction was again modified so that 37 roads covering a distance of 693 ri, to be carried out in six years commencing from the fiscal year 1911, was undertaken. These, constructed entirely by the Central Government, added to those already constructed by the State Government before annexation, we find that these years show a total of 761 ri. By local governments during the period up to 1915 we find that with the aid of State grants 426 ri was completed. From local expense funds during this period 989 ri was completed. Table No. 3 gives details as to the per centage of roads of different classes planned and completed up to this period. Up to the end of March 1917 we find that a grand total of 9,102, 880 yen had been expended on roads, showing 637 ri of completed state roads. Mention should be made in this article of bridge construction as carried out in connection with the road programme. Unfortunately in most instances on account of the lack of funds, wooden bridges and culverts were constructed with the result that they either went out [page 45] with the first heavy rains, or after a few years collapsed from dry rot. This is unfortunate, as in most cases natural material was close at hand and the importation or bringing in over the newly constructed roads of cement for the building of concrete bridges could have been accomplished with little additional expense. In some cases where concrete bridges were constructed the engineers and surveyers showed great lack of knowledge of local conditions and rainfall with the result that many of this class of bridges and culverts went out with the first rain. These bridges of both types have not been replaced as fast as they should have been, with the result that in many instances detours still have to be made, while in some cases in the rainy season crossing is impossible. The engineers in charge have also resorted at times to the pontoon bridge, which method is an economical as well as practical one and could be resorted to more often. The fine steel bridges across two of Korea’s great rivers, the Han and the Taidong, will long remain as a monument to the skill of the engineers in. charge of this particular work. The Han Bridge is 1449 feet across the main span and 621 feet across the branch span. Roth have two side-walks or foot paths 6 feet wide, while the main driveway is 15 feet wide. It was thrown open to the public in September 1917, while the Taidong Bridge was opened in 1923. (See Table 4.) The year 1917 saw the completion of the first programme of work in sight, and the initiation of s second programme calling for the construction of 25 first and second class roads measuring 477 ri in all, with the building of nine steel bridges across important rivers at the cost of 7,500,00. The work on this programme began in October 1917 and continued over a six year period up to 1922. To the end of March 1920 the Table No. 5 will give an idea of the first and second class roads actually completed. Besides the first and second programme previously men-tioned, and the money involved therein, the Central Govern-ment has annually subsidized the provinces to the extent of ¥100,000 to ¥300,000 annually to assist them in the building of third class roads. [page 46] I attach hereto a comparative Table No. 6, brought out by the Government in 1918, which shows the number of vehicles past and present. I think it is intensely interesting and speaks well for the economic result of road construction. Table No. 7 gives in detail the roads planned and under construction of the first and second class type for the different provinces, and while, as in my other tables, the figures are in ri, they can be easily converted into miles when it is remembered that 1 ri equals about 2.44 miles. By bringing my figures, tables and statistics up to date, I hope patient reader or listener to take you to a subject that will be more interesting, at least it was so to me, but in writing an article of this sort we must remember that there are certain students who get pleasure from delving into figures, and their supreme joy is to find errors. Of them I am asking leniency, as the subject which brings joy to their hearts has been a nightmare to me and the cause of the asking for postponement of the reading of this article twice before the event actually happened. The latest figures on road construction that I have been able to procure, bring this part of my article up to March 31st 1923, and give in detail the completed and uncompleted roads, first, second and third class, with their distribution throughout the different provinces. The use of this table in conjunction with a map of Korea and the table entitled “Distribution of Roads,” which immediately follows, will give one a very good idea of the wonderful network of roads that covers Korea. See Table No. 8 “Planned Roads.” Constructed and under Construction. To give an idea as to what is being expended on the yearly upkeep of these roads, the majority of which is going into the replacement of the bridges previously mentioned, I will mention the ¥1,600,000 defrayed and used in the year 1922. It is estimated that a further Yen 6,000,000 is needed to complete the reconstruction of all bridges of the type previously referred to, and the ballasting of these roads, which UNDEVELOPED COUNTRY WHICH IS BEING OPENED UP BY NEW ROADS[page 47] in many instances have not had more than a dirt covering. Due to the Tokyo Government’s policy of retrenchment in Korea, it looks as if the ‘‘Puyok” system will have to be strictly enforced, where by five men’s labour for one day a year from each house located within 10 ri of the place where the repair work is to be done. Why should it not be ? Would it not be criminal to allow our fine system of roads to revert back to conditions described in the first part of my article, when farm labour, which at certain times of the year without interference to the farmers’ routine work, is plentiful, and can be thus enlisted ? Before going to that part of my article, already promised, and which will be as free from statistics as I can make it , I wish to mention the enormous growth in the use of auto mobiles, and when I refer to such I mean the Ford principally. In 1911 there were two automobiles in the country, while at the end of 1922 the number had swollen to 935. In comparison with Formosa and Japan they make no mean showing for at the end of March 1922 Japan proper had only 8,265 cars and 1,383 trucks. The taxi, or jitney service, almost entirely Fords, now forms a very important branch of the transport system of this country, and the next few years will see a much greater proportionate growth. In the southern part of Korea there are very few cities not touched by the railroads that cannot be reached by motor. The total length of the roads traversed by jitney service has risen from 1,053 ri in 1919 to 2565 ri or 6258 miles (1 ri- 2-.44 miles) in January 1923. The total length of railroads of all descriptions, standard and light gauge, at this time totalled only 1,454 miles. With the general economic depression there is little doubt in the writer’s mind that the repair and upkeep of the State highways by methods previously mentioned, and encouragement by the state of country jitney service is essential and must be carried out by the State. It has been hoped that the Government would see its way clear to the continuation of automobiles on the duty free list, thereby encouraging the companies, who have invested heavily, to replace their present cars with those of a later model, and at[page 48] the same time encourage others to start new services. Civilized man, when he first sets foot on a strange land, looks for a road inland, and when be fails to find one, sets to work to build one. It is the first act of the pioneer, and Japan has surely lived up to traditions. Without roads there can be no transportation, and without assistance and co-operation from the Government there can be no motor transportation. The policy of petty officials and the general public in looking upon the motor car as the toy of the rich must go, and a policy of education as to the important part the car is playing today in Korea’s transportation problem must be inaugurated. The story of Japan’s rule in Korea will always be closely linked with the construction of the roads throughout the peninsula and the real opening of the interior of the Hermit nation to easy and accessible means of transportation. They have driven their roads over long stretches of rice land, over mountain and hill, long and straight, leaving on the physical features of the country an indelible mark. BRIDGE ACROSS THE HAN RIVER, SEOUL TYPE OF BRIDGE NOW BEING ERECTED IN COUNTRY [page 49] [page 50] [page 51] [page 52] SECOND CLASS ROAD SECOND CLASS ROAD OVER MOUNTAIN PASS PLANNED ROADS. Constructed & Under Construction. FIRST CLASS ON MARCH 31ST, 1923. SECOND CLASS. [page 54] THIRD CLASS. [page 55] SECOND CLASS ROADS. [page 56] SECOND CLASS ROAD CONSTRUCTION