Diabetes Workforce Service Forecast

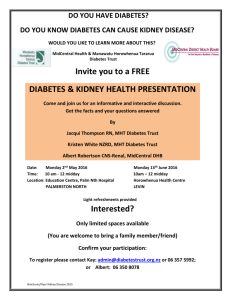

advertisement