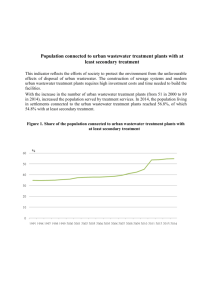

Progress against the national target of 30% of Australia`s wastewater

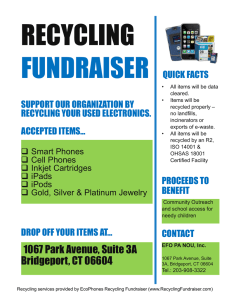

advertisement