Chapter 14 Summary There was, of course, plenty of industry in the

advertisement

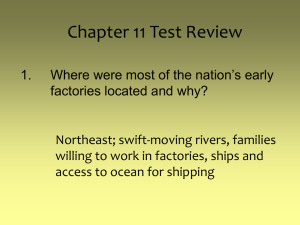

Chapter 14 Summary There was, of course, plenty of industry in the United States in 1792. All of them, however, were small businesses dependent on the skills of their owners, employing very few people, and serving only local markets. Transforming fleeces into cloth involved innumerable men, women, and children performing one or two steps of the process. Woolens manufacture had been central to England’s economy since the Middle Ages. What England’s weavers needed was a more productive way of spinning yarn. The spinning machines of the late 1700s (and, soon enough, mechanized looms) were revolutionary. The Industrial Revolution found its American home in the northeastern states. Through acts of technological piracy, the United States was able to smuggled cotton mills, woolen mills, and power looms into the country. Textile production was centered in the northeastern states because of its abundance of water power. The Northeast was also rich in capital that was diverted to manufacturing before and during the War of 1812. Americans soon numbered among the pioneer innovators in other industries. Oliver Evans of Philadelphia earned international fame when he contrived a continuousoperation flour mill. Eli Whitney, already famous as an inventor, designed a rotary metal-cutting machine with which, he believed, he could mass produce muskets. The vision of interchangeable parts and mass production intrigued manufacturers of many kinds. Some factory owners hired entire families to work their mills. More successful was the “Waltham System” or “Lowell System.” Farmers were urged to send their grown girls to work in mills for six days a week, about twelve hours a day, for weekly wages of $3. In 1782, African American slavery appeared to be dying out. By 1808, however, cotton culture was returning bonanza profits. Eli Whitney’s cotton gin revived the one-crop economy that planters of Washington’s generation had considered the South’s curse. The demand for “prime field hands”— young, healthy men—to toil in the cotton fields caused the price of slaves to soar. The population explosion west of the mountains in the early 1800s was not restricted to the cotton belt. The abundance of cheap land does not by itself explain the torrent of people that flooded west. A few of these eternal pilgrims were simply antisocial. Others were respectable and wanted as much company on the frontier as they could persuade to join them. Yet other pioneers were speculators and developers. Cities preceded farms along major rivers. Most astonishing is how quickly some western cities became manufacturing centers. Speculators were intensely interested in the price at which the federal government disposed of its land and the terms of purchase. Land law was revised to favor big-time speculators. In 1819, the price of cotton collapsed, causing bonafide planters to default on their loans. Nationwide, about half a million wage workers lost their jobs. Much of this was because of massive land speculation. Squatters were settlers who developed farms on public land before the government offered it for sale. Squatters and their sympathizers turned to Congress for help with their legal rights to the land.