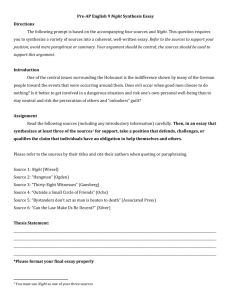

THE ARGUMENTATIVE ESSAY (C Exc)

advertisement

THE ARGUMENTATIVE ESSAY The Argument An argument uses evidence to support an opinion through a process of reasoning. Arguments in academic writing are usually complex and take careful effort to develop. The process of constructing a supported argument leads to further understanding and clarification of ideas. In academic contexts, the process is one of rational discourse: claim, evidence, consideration, and rebuttal of objections and conclusion, all intended to appeal to the open mind and reasoned judgement of the reader. In academic circles an argument is regarded as the presentation of an opinion through the process of reasoning and providing proof. In academic writing an argument is sometimes called a claim or a thesis statement, backed up with supporting evidence. Thesis statement: “A person who knows all the grammar and all the vocabulary of a language does not necessarily ‘know’ that language.” Support: As noted by the sociolinguist Dell Hymes in his essay “On Communicative Competence’, there are rules of use without which the rules of grammar would be useless (Hymes 1972). In this case the support is in the form of a quotation from a well-known sociolinguist. What is not an argument? Impossibilities: for example, that men should bear children. Preferences: because they cannot be subjected to logical process, they too cannot be argued. For example, musical preferences cannot be subjected to rational debate. Beliefs: any matters which are outside the bounds of empirical truth, such as religion, are also beyond the borders of argument, because they cannot be proven Components of an argument Terms There are a great variety of terms used to describe the individual components of an argument. There are a few models of argument structure, each with their own sequence and structure. In some cases the individual terms used have slightly different meanings depending on which model of argument presentation is being used. As the main focus of these materials is on 1 development of argument structure in academic writing, the terminology used in this field will be used. In brief, a written argument consists of a specific position on an issue with supporting points. Some of the other terms used are in the box below: The building blocks: Argument Thesis Statement Main claim Assertion Premise Proposition Conclusion Support E. G. /Examples Supporting points Evidence Reasons Citations/Experts’ opinions Strong arguments anchor the thesis statement with evidence The most important part of any argument is the thesis statement/main claim etc. Normally a thesis statement will do one of the following three things: make a judgement about something, offer a solution or recommendation, or explain something The Toulmin Method The basic format for the Toulmin Method is as follows: Claim: The overall thesis the writer will argue for. Data: Evidence gathered to support the claim. Warrant (also referred to as a bridge): Explanation of why or how the data supports the claim, the underlying assumption that connects your data to your claim. Backing (also referred to as the foundation): Additional logic or reasoning that may be necessary to support the warrant. Counterclaim: A claim that negates or disagrees with the thesis/claim. Rebuttal: Evidence that negates or disagrees with the counterclaim. 2 Including a well thought out warrant or bridge is essential to writing a good argumentative essay or paper. If you present data to your audience without explaining how it supports your thesis they may not make a connection between the two or they may draw different conclusions. Don't avoid the opposing side of an argument. Instead, include the opposing side as a counterclaim. Find out what the other side is saying and respond to it within your own argument. This is important so that the audience is not swayed by weak, but unrefuted, arguments. Including counterclaims allows you to find common ground with more of your readers. It also makes you look more credible because you appear to be knowledgeable about the entirety of the debate rather than just being biased or uniformed. You may want to include several counterclaims to show that you have thoroughly researched the topic. Example: Claim: Hybrid cars are an effective strategy to fight pollution. Data1: Driving a private car is a typical citizen's most air polluting activity. Warrant 1: Because cars are the largest source of private, as opposed to industry produced, air pollution switching to hybrid cars should have an impact on fighting pollution. Data 2: Each vehicle produced is going to stay on the road for roughly 12 to 15 years. Warrant 2: Cars generally have a long lifespan, meaning that a decision to switch to a hybrid car will make a longterm impact on pollution levels. Data 3: Hybrid cars combine a gasoline engine with a battery-powered electric motor. Warrant 3: This combination of technologies means that less pollution is produced. According to ineedtoknow.org "the hybrid engine of the Prius, made by Toyota, produces 90 percent fewer harmful emissions than a comparable gasoline engine." Counterclaim: Instead of focusing on cars, which still encourages a culture of driving even if it cuts down on pollution, the nation should focus on building and encouraging use of mass transit systems. Rebuttal: While mass transit is an environmentally sound idea that should be encouraged, it is not feasible in many rural and suburban areas, or for people who must commute to work; thus hybrid cars are a better solution for much of the nation's population. Induction and deduction Induction and deduction are the processes of reasoning used to arrive at a conclusion based upon available evidence. A logical argument can take two shapes: 3 Inductive In inductive reasoning individual points are presented and a conclusion is reached based on the sum of the evidence that is presented. In effect evidence is presented and then a conclusion is arrived at based on the evidence. This strategy is particularly useful if it is unsure whether the audience will agree with your arguments. In fact one is showing them how one has gone from particular evidence to a conclusion. This is just like detective work where individual clues lead to a decision about a crime. It goes from specific to general. It is a process of drawing conclusions or making generalizations based on several examples. It is the process of reasoning from the particular to the general. Induction is used widely in areas where there is collection of information and the creation of conclusions based upon that information. Arguments that rely for the persuasiveness of its conclusion on collection of data, on measurement on information collected in any way are generally inductive arguments. Much of the work done at undergraduate level will be using inductive methods: you need to identify and use what counts as evidence in the particular field: collect the information, classify it and reach an appropriate conclusion based on the evidence collected. Deductive Deductive reasoning or a deductive argument moves from general to specific. First a general idea or principle is presented followed by more specific arguments. Applying a generalization to a particular case. Deduction is often used when we begin an argument with something that about which there is general agreement and then this is applied to a particular case, or interpreted that example in the light of that general truth. Logical reasoning Some kinds of logical evidence are more convincing than others More convincing: Deductive reasoning inductive reasoning referenced facts statistics opinion of experts examples analogies Less convincing: Hearsay evidence Unreferenced facts Non-expert opinion Anecdotal evidence Syllogisms The simplest form of deduction is a syllogism. A syllogism consists of three parts: the major premise, the minor premise, and the conclusion. The major and minor premises are based on underlying assumptions from which one makes a point. By considering the two together a logical conclusion can be reached. The reasoning process dictates that if both premises are true, the conclusion must also be accepted as true. The term syllogism is used to describe the three part structure that is often used in deductive arguments. 4 Linguistics is a challenging field of study (general idea) I enjoy challenging work (general idea) I will enjoy linguistics (specific argument) If all humans are mortal, And all Greeks are human, Then all Greeks are mortal. Argumentative essay structure The introduction The purpose of the introduction is to lead the reader into the topic and focus on the specific area or arguments to be presented in the essay. Introducing the Topic: The first step is to capture the readers’ attention and provide orientation to the topic to be discussed. This can be referred to as the Introducing the Topic or IT move. Readers need to be convinced of the importance of the issue. Narrowing the Focus: The topic needs to be defined and limited if necessary, so the second move of an introduction is Narrowing the Focus or NF, which may consist wholly or partly of definitions of key terms used throughout your essay. The introduction normally should lead from general to specific in content. Central Idea (CI) The thesis statement, or Central Idea (CI), placed at the end of the introduction, states the position to be presented in the essay by giving a concise summary of the arguments that will be defended and supported in the essay. It should provide a precise viewpoint to be argued in the essay. Example: Introducing the topic – I T The English Language is normally considered to be based in the United Kingdom and the United States of America, with its other centres in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. Narrowing the focus – N F However, in this globalized era where English has become a world language, a case can be made for English being even more pluricentric and not just the property of its ‘native speakers’. Central Idea – C I This essay will evaluate the arguments in favour of English, or rather ‘Englishes’ being the property of the majority who speak it alongside their other languages. 5 The essay body The body of the essay is the section in which the arguments are presented and supported with relevant details. The body contains the details that will attempt to persuade the reader of the validity and veracity of the arguments. As a rough guide it is advisable to write at least one paragraph presenting and supporting each of the arguments. The arguments need to be divided into separate meaningful categories. The support for each point will be in the form of reasons, specific example, facts, cases or expert testimony. The structure for each point or paragraph is Main Idea (MI) followed by Support (S), which may take the form of examples, evidence, statistics, quotations or references. Counterarguments/Refutation In order to display a balanced and a deeper understanding of an issue, it is necessary to acknowledge the objections to the arguments that you intend to present. Ignoring the opposing views can be counterproductive because the audience will be aware of the opposing arguments and will doubt the credibility of an essay that ignores them rather than dealing with them openly and honestly. Considering one or two counterarguments in depth is better than merely presenting a long list of all the possible counterarguments. It may appear contradictory to show the opposing arguments, but there are a number of reasons for doing so. It shows the reader that no information or information has been neglected. The creditability of the write is also enhanced as the reader sees that the opposite views have been carefully considered. The conclusion The conclusion is a very important part of the essay because it sums up the thesis and support for it. In the conclusion you should restate and summarise, in brief, the main arguments. This is called the CC move (Commitment to the Central Idea). It is best to rephrase the thesis statement as the essay has focussed on arguing and supporting the point. Give the reader a clear picture of your position and reasons for taking it. Avoid adding any new arguments that have not been presented in the body of the essay. In contrast to the introductory paragraph, the conclusion moves from specific to more general matters. The wider implications of the issue can be discussed briefly culminating in a final appeal to the reader, known as the Expansion (Ex) move. Model Essay Structure A model for the structure of an academic essay, which can be used as part of your planning process, might look like this: Introduction IT – Introduction of topic NF – Narrowing of focus CI - Central idea Body M1 (Main idea) Support 1 6 M1 2 Support 2 MI 3 (Counterargument 1) Support/ refutation 3 MI 4 (Counterargument 2) Support/ refutation 4 Conclusion CC – Commitment to Central Idea Ex - Expansion Sources: http://cedar.humanities.curtin.edu.au/TeachingMat/OLLD/Argument/6-0.cfm http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/section/1/2/ http://www2.winthrop.edu/wcenter/handoutsandlinks/classica.html 7