Romero-Wagner Bank Run Project - Gmu

advertisement

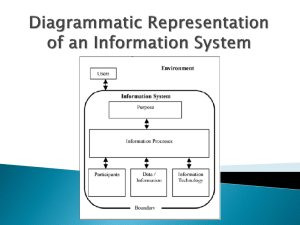

Viennese Kaleidics: Why it’s Liberty more than Policy that Calms Turbulence Richard E. Wagner Department of Economics, 3G4 George Mason University Fairfax, VA 22030 USA tel.: ++1-703-993-1132 fax: ++1-703-993-1133 rwagner@gmu.edu http://mason.gmu.edu/~rwagner Abstract The idea of a kaleidic economy or society is strongly associated with George Shackle and his vision of Keynesian kaleidics. This essay asserts that the central thrust of the Austrian tradition in economic analysis can be described by the term Viennese kaleidics. In either version of kaleidics, the analytical stress is placed on treating time seriously and not just notionally. Either version of kaleidics leads to recognition that economic processes are better treated as turbulent than as equilibrated. While that turbulence is a natural feature of the unavoidable incompleteness of intertemporal coordination, it is subject to mitigation. This essay explains how it is that individual liberty and private ordering is generally superior to state policy and public ordering in calming the turbulence that naturally characterizes a kaleidic economy. Keywords: kaleidic economy; George Shackle; time and economics; monetary non-neutrality; private vs. public ordering JEL Codes: B20, D20, D80, E30, E52, E62 Viennese Kaleidics: Why it’s Liberty more than Policy that Calms Turbulence1 My title entails two claims that I think comport with the central insights and intuitions that Carl Menger (1871, 1873) set forth in articulating what became the Austrian tradition of economic theorizing. One claim is indicated by the title: the appropriate Austrian framework for economic analysis is of a kaleidic and not an equilibrated society. In light of the organonic quality of economic theory, this claim ramifies throughout the corpus of economic scholarship, as Wagner (2010) explores in his contrast between neo-Mengerian and neo-Walrasian research programs. The other claim is indicated by the subtitle: while a kaleidic society is naturally turbulent, the road toward calming that turbulence lies more in the direction Liberty than in the direction of Policy. This second claim clashes sharply with the standard presumption that collective action must be paramount in any effort to counteract kaleidic-related turbulence. The bulk of this paper is devoted to explaining why it is that liberty, which is the source of turbulence, is also the primary road along which tools for the control of turbulence may be found. Kaleidics is, of course, associated with George Shackle (1972, 1974), who asserted that Keynes (1937) was the source of his kaleidic vision. Ludwig Lachmann (1976) argued in turn that Mises (1966) and Shackle reflected complementary theoretical orientations. It’s readily conceivable, moreover, that 1This is a revised text of my presidential address to the Society for the Development of Austrian Economics, Washington, DC, November 20, 2011. I’m grateful to Peter Boettke for offering helpful comments on an earlier version. 2 had Keynes (1936) never been published, leaving Keynes (1937) to stand alone, Lachmann might have extended his discussion to Keynes, for Keynes (1937) sketches the kaleidic vision that Shackle (1974) deepens. But this is conjecture, and my desire is to offer not conjecture but a line of analysis that explains why Viennese kaleidics provides a sensible orientation for our tradition, and how in turn Viennese kaleidics explains how the control of turbulence requires an expansion of liberty relative to policy. Viennese kaleidics differs in two significant ways from Keynesian kaleidics, both of which point to the infirmities of policy as a tool for calming turbulence. One of those ways is a distinctly different way of moving from micro to macro levels of theorization, where Viennese kaleidics, in contrast to Keynesian kaleidics, recognizes that macro variables are results of human action but are not direct objects of choice. Viennese kaleidics recognizes that an economy is a complex ecology of plans that resembles a living organism and is nothing like a machine that can be engineered and re-tooled. The other point of difference is recognition that the use of Power to impose Policy impedes the assembly of knowledge that is distributed throughout the catallaxy, thereby generally promoting rather than calming turbulence. Turbulence is, of course, a concomitant of liberty. Policy is commonly advocated as a type of Faustian bargain (Ostrom 1996) wherein compulsion replaces liberty so as to calm turbulence. Viennese kaleidics explains why the tradeoff envisioned in that bargain is dubious, with the reality being that the compulsion of Policy often intensifies turbulence. 3 1. Viennese Kaleidics: Reality Uncovered or Nihilism Espoused? Ludwig Lachmann (1976) uses kaleidics to connect Ludwig von Mises and George Shackle while arguing that Shackle extended Mises’s insights in three directions: (1) extending subjectivism to expectations, (2) treating choice as an act of imagination as a consequence of treating time substantively and not just notionally, and (3) recognizing that markets, especially asset markets, reflect a divergence and not a commonality of expectations, thereby abandoning any presumption that the market process tends in the limit to some state of general equilibrium. In concluding, Lachmann (p. 61) opined that kaleidics “is thus not the natural habitat of Austrian economics, but the alien soil may prove nourishing.” While I agree about the nourishing quality of the kaleidic soil, I also think that kaleidics is the natural habitat of Austrian economics. Following Wagner (2010), economic theory can be formulated within a kaleidic-Mengerian frame of reference as well as an equilibrium-Walrasian frame of reference. In advancing the claim that kaleidics is the natural habitat of our tradition, I would enlist Sandye Gloria-Palermo’s (1999) examination of the Austrian tradition from Menger to Lachmann in my support in lieu of an extended discussion of our tradition to economize on the limited space I have for this presentation. I should also mention that many notable Austrians regard the ShackleLachmann influence as an alien injection into our tradition, one that offers not nourishing soil but corruption of hard-gained truths. These critics of kaleidics do not voice foolish objections. Their objections reflect the belief that the kaleidic vision is contrary to the Austrian effort to uncover and articulate objective claims 4 about reality. Analytical nihilism, where analysts are free to see what they choose to see, would replace the hard-earned Austrian effort to uncover objective truths about a societal reality that we all experience. In this respect, Murray Rothbard (1990) speaks of the “Hermeneutical Invasion of Philosophy and Economics.” And in his treatment of what he regards as Lachmann’s nihilism, Joseph Salerno (2002) reports that Rothbard referred to “Lachmannia” as a disease that has been infecting some Austrian seminar rooms. In a similar vein, Leland Yeager (1997) counsels Austrian theorists not to be scornful of theories of general equilibrium.2 Analytical nihilism and analytical solipsism are certainly contrary to the Austrian tradition, for the participants in that tradition have always sought to uncover features of the societal reality that is common to all of us. Yet that reality is not an object that is directly accessible to an analytical observer. We can observe directly both rainbow trout and the insects that fly near water. Having done that, we can theorize about how the insect’s appearance when it approaches water inspires the trout to bite. In light of that knowledge, we might try to design artificial insects with hooks. However we might go about doing this, our object of theoretical interest is available for our direct examination. The situation is different for much of the material of the social sciences. An economy, for instance, is not directly apprehensible, but is apprehensible only in light of 2 In contrast to the Austrian critics of what they perceive to be the nihilism of kaleidics, Stephen Parsons (1993) argues that it is orthodox economics, with its readiness to embrace fictive models that give definitive answers to questions that is nihilistic. Warren Samuels (1993) notes that if the charge of nihilism is applied to any system of thought that leaves the future open, nihilism is superior to the alternative. 5 some prior act of theorization. Equilibrium-based theories take a different tack to the construction of those objects of theoretical interest than do kaleidic-based theories, but both sets of theories seek to create knowledge that is independent of the theorist. While Menger rejected Walras’s claim that both of them were working to advance the same conceptual framework, the Walrasian idea of an orderly system of relationships has pervaded the corpus of Austrian theorizing. Ludwig von Mises’s (1966) formulation of an evenly rotating economy gives recognition to this systemic quality. Friedrich Hayek’s (1932) treatment of the business cycle as departing from a position of Walrasian equilibrium is a similar effort. Neither theorist was working with the Walrasian apparatus, but both used that apparatus as a stalking horse to advance their arguments. In doing this, they sought to use their theoretical formulations to illuminate features of reality that they recognized as existing independently of their theoretical efforts. Kaleidics apparently seems to the critics to eliminate the prospect of advancing claims about an objective reality, and to replace those claims with statements that are the private property of the observer. In the presence of kaleidics and its replacement of knowledge with unknowledge, the objective quality of reality would seem to vanish into that fog of unknowledge. The future becomes akin to one of those ink-blot patterns that psychologists use to elicit responses from subjects. In this setting, there is no right or wrong answer about what the ink-blot represents, for the examiner simply wants to know what comes to the subject’s mind upon seeing the ink-blot. Theorizing within a kaleidic 6 framework, however, is not to deny the objective quality of reality; it is rather an effort to explain significant aspects of that realty. The analyzing subject is not offering reactions to ink-blots but is uncovering something real about those inkblots. In undertaking this uncovering, Viennese kaleidics offers a path to penetrate more deeply into that reality.3 To achieve that penetration, however, requires a theoretical framework suitable for the task. The Walrasian framework reduces society to a snapshot and asks the theorist to give an account of the picture, and with comparative statics used to account for changes observed over a sequence of pictures. The evenly rotating economy replaces the snapshot with a film that continually repeats itself. Viennese kaleidics likewise employs the image of the film, only that film shows a continuing parade of novelty along with the continuation of a good deal of familiarity. It is this conjunction of familiarity and novelty that comprises the objective reality that Viennese kaleidics seeks to penetrate. For this penetration to be achieved, however, some shift in the variables of analytical interest is necessary. For Walrasian-based formulations of societal equilibrium, the variables of interest must be resource allocations, for there isn’t anything else that can be of interest when time is eliminated as a substantive feature of the analytical effort, as O’Driscoll and Rizzo (1985) explain. For Viennese kaleidics, however, time is treated substantively, which means in turn that experimentation and novelty continually enter society. Kaleidic turbulence is 3 In their examination of the scholarly oeuvre of Elinor and Vincent Ostrom, Alegica and Boettke (2009) explain that the Ostroms sought to penetrate deeply into reality in contrast to the Walrasian-like posture of achieving separation from reality. 7 a feature of society, though so also is a good deal of familiarity, as Koppl (2001) explains in his effort to inject both novelty and typicality into choice. A kaleidic society generates debris due to the collision among plans that has no place in the Walrasian framework. Hence, Viennese kaleidics opens into questions concerning how people deal with that debris, which brings to the foreground questions concerning the governance of human relationships and interactions, pushing into the analytical background questions concerning the allocation of resources because allocations emerge out of patterns of governance. Related to this reversal of foreground and background is recognition that the subject matter of economics is more suitable for plausible than for demonstrative reasoning, with this distinction being articulated mathematically by Polya (1954) and economically by Clower (1994, 1995). By its very nature in treating time substantively, kaleidics cannot be pursued to demonstrate societal equilibrium. Likewise, any demonstration of societal equilibrium must neuter the passing of time that is central to the Austrian orientation. Viennese kaleidics operates within the framework of plausible reasoning, which is an open and not a closed system of thought; therefore, it cannot lead to statements that must be accepted of demonstrable necessity within the context of the framing axioms. With respect to plausibility, we can see from observation that societies are both orderly and turbulent, and with the mix between orderliness and turbulence varying through time. It is a reasonable theoretical aim to seek to explain historical variability in the mix of orderliness and turbulence, provided, however, that the theoretical framework is able to give space to both. An equilibrium 8 framework cannot do that. Rather, a kaleidic framework is required, but not just any kaleidic framework. 2. Viennese Kaleidics and its Keynesian Cousin All theorizing about societal turbulence recognizes that equality of aggregate saving and aggregate investment is a necessary condition for the absence of turbulence. Equilibrium theories postulate this condition as denoting equilibrium in the market for loanable funds, thus reflecting the pre-coordinated character of this theoretical framework. Within this mechanical or hydraulic framework, it is easy to perform comparative static exercises. Hence, a presumed decline in private investment can be offset by increased public spending to maintain constancy in total spending. To be sure, controversy exists among equilibrium theorists over the coherence of this framework. Among other things, increased spending increases public debt, and the present value of the future taxes which that debt entails may reduce private spending. Regardless of controversies among equilibrium theorists, a kaleidic framework stands apart from any equilibrium framework, due to the substantive treatment of time, which entails in turn the absence of pre-coordination as a conceptual device. Both Viennese and Keynesian kaleidics embrace the distinction between ex ante and ex post. Indeed, it is the operation of phenomena related to and captured by this distinction that is the source of kaleidic turbulence. Ex ante refers to anticipations on which plans are based. Ex post refers to some accounting of the results of those plans at some later date. Any 9 plan spans time by creating a bridge from present when the plan is formed to some future point, or set of points, where the outcome of the plan is appraised. Reminiscent of the Ptolemaic astronomers, many equilibrium theorists have sought to maintain adherence to timeless formulations by assuming that people form expectations rationally, which in turn is treated as forming plans today based on statistically accurate projections of economic conditions at the time the plan reaches maturity, subject only to random variation. Within an analytical framework based on the timelessness of pre-coordination, this is a reasonable and even necessary theoretical construction, even though it renders change an exogenous shock rather than an internal quality of economic interaction. For a theoretical framework that seeks to locate change as an internallygenerated feature of an economic system, it is necessary to take time substantively and to allow the passing of time to do significant analytical work. This is the analytical target at which both Viennese and Keynesian kaleidics aim. Keynesian kaleidics start with recognition that equality between saving and investment is problematical and elusive, and not something to be imposed by assumption simply to close a model, as illustrated by Keynes (1937), Leijonhufvud (1968), Clower and Leijonhufvud (1975), and Shackle (1972, 1974). The transformation of saving into investment requires intermediation between different sets of people, and is unlikely to proceed so smoothly as theories grounded in presumptions of pre-coordinated equilibrium would lead us to expect. Turbulence would be a feature of this kaleidic framework, though we might think, based both on theoretical understanding and historical observation, 10 that such turbulence would be mostly modest, perhaps as illustrated by Leihonhufvud’s (1981) thesis that the amplitude of turbulence is generally bounded by a corridor. Viennese kaleidics contains two theoretical features that distinguish it from Keynesian kaleidics, and these I will examine in the following two sections. One difference resides in economic theory; the other difference resides in political economy. The economic difference pertains to the relationship between micro action and macro phenomena. Where Keynesian kaleidics treats macro phenomena as susceptible directly to choice, Viennese kaleidics recognizes that macro phenomena can be reached only through pathways that originate at the micro level where all human action occurs. With regard to political economy, Viennese kaleidics recognizes that limited and distributed knowledge pertains to all actors in society, both public and private. There are, moreover, plausible grounds for thinking that private ordering is generally superior to public ordering in its ability to promote the effective creation and use of knowledge that is necessary for the calming of kaleidic turbulence. In consequence, the control of turbulence must to a large extent run through private ordering and not through public ordering or interventionist policy. 3. The Micro-Macro Relationship: Indirect and not Direct Keynesian kaleidics works with a particular type of representative agent formulation where the prime analytical interest is placed on savers and investors as classes that act pretty much in unison. Those actions, in turn, exert direct 11 effects on macro variables. With macro variables thought to be directly accessible to change through policy, a policy of acting on aggregate demand when an economy would otherwise escape its corridor of stability can thus serve as an instrument for restraining the negative consequences of kaleidic turbulence. This type of remedy is perhaps sensible if an economy is properly conceptualized as a single entity or organization that can be acted upon through policy, much as a cue ball can act upon a billiard ball. Keynesian kaleidics follows the analytical framework of conventional macro theories in reducing macro variables to micro variables through treating constructed aggregate variables as direct objects of action. Viennese kaleidics recognizes the infirmities of this conceptual framework, due to recognition that societies are orders that contain multiple organizations, each of which pursues its particular plans within the societal ecology of plans. The relationship between micro and macro is one of supervenience and not one of reduction. Macro variables are constructed objects that reflect emergent qualities of interaction among micro entities. Investments, for instance, are always directed at particular commercial plans, and are direct objects of action to those who determine those plans. The construction of some measure of aggregate investment is not an object that anyone acts on directly. Macro variables are not truly objects of direct action, but rather are objects that can only be influenced indirectly as actions on the micro level are projected onto the macro level. With this alternative conceptualization, an economy is better conceptualized as a networked ecology of enterprises. Within this ecology, all 12 action takes place at the micro level where people, businesses, and governmental agencies operate. An increase in government spending necessarily enters the economy at particular places within this ecology of plans. What results thereafter depends on the state of the plans where the spending enters. A particular commercial plan, moreover, will operate within a network of complementary plans. Figure 1, based on Wagner (forthcoming), illustrates this idea. The micro level is where all action occurs. Shown there are two types of entity. The circles denote market-based entities or enterprises; the triangles denote politicallybased entities. This distinction between types of entity will become significant in the next section. All of these entities comprise a network that constitutes an economy. The connections among entities denote various commercial and regulatory interactions among the entities. What is especially notable about this graph is its polycentric character: the economy, including political entities, is an order and not an organization. The three lightning bolts that run from the micro level where all action occurs to the macro level which is the locus of a congeries of statistics, projections, and ideologies indicate that macro phenomena emerge out of interaction among entities operating on the micro level. In Figure 1 the macro level is denoted by the standard framework of aggregate demand and aggregate supply. Shown there is as increase in aggregate demand such as might accompany some fiscal expansion under some but not all equilibrium-centered models. That expansion, however, is not in any case the direct result of policy 13 action. Any expansion must enter at particular nodes in the micro ecology. What happens from that point of injection depends on choices that are made at that point and on the pattern of relationships that emanate from that node and spread into the ecology. The same point holds for monetary expansion as holds for fiscal expansion. Money likewise enters at particular nodes within the micro ecology of plans simply because there is no other way for money to enter that ecology. Each node denotes a plan within the ecology of plans. Any expansion thus supports particular nodes within the ecology. Whatever aggregative effects might result will depend on the changing patterns set in motion by that expansion. Expansion supports experimentation, and in this way exerts real effects on the economy. This is not to say that monetary expansion would necessarily exert detectible effects on aggregate measures of real income. Monetary expansion can bring about structural changes in patterns of activity without affecting standard measures of aggregate activity, as illustrated by Wagner’s (2010: 14849) illustration of how monetary expansion might influence the geographical distribution of land rents without affecting the aggregate value of land rents. Such expansion, whether of a monetary or fiscal nature, will promote particular commercial activities relative to other activities that might have been promoted with different points of injection. Viennese kaleidics offers a vantage point for understanding the non-neutral character of monetary or fiscal activity: real effects result from nominal injections because different points of injection amount to selection of different plans to expand within the ecology of plans. 14 Learning accompanies plan-based activity, so that expansion channels learning in particular directions in the vicinity of those points of injection. In turn, commercially adjacent nodes within the ecology will learn of new opportunities, which will cause further turbulent modification within the ecology of plans. If that expansion arises through subsidizing credit for wind-power projects, learning will center on various activities and technologies associated with wind-power. If, instead, it arises through subsidizing credit for constructing bicycle paths in metropolitan areas, learning will center on activities complementary to cycling. With time being treated substantively, evolutionary processes of spontaneous ordering will bring about substantive changes in the pattern of activity within the societal catallaxy. In this manner, non-neutrality characterizes monetary and fiscal activity; however, the presence of non-neutrality would appear in the bottom part and not the top part of Figure 1. 4. Distributed Knowledge, Viennese Kaleidics, and Political Economy Keynesian kaleidics construes an economy as a machine that is subject to repair by an experienced mechanic. To be sure, the machine is construed as being comparatively complex in contrast to the simplicity of timeless equilibrium. Still, the problem of policy is treated as one of diagnosis followed by repair. This formulation involves two presumptions that offer targets for reconsideration. One target is the presumption that relevant knowledge can be assembled and centralized. The other target is the presumption that such knowledge, if assembled, will be used in an ameliorative manner. Both of these presumptions 15 reflect what Roy Harrod (1951) described as the “presuppositions of Harvey Road” in his biography of Keynes. Those presuppositions were that British policy was conducted by an enlightened few who could be counted on to do the right thing. Relevant knowledge was capable of being assembled, and once assembled it would be used properly. Viennese kaleidics reveals some problematic features of this orthodox framework for policy analysis. Aggregate variables involve reductions in information from what operates within the ecology of plans. Those statistics might speak to the quantity of pencils produced over some interval or to the inventory of pencils held by producers at some date. It would even be possible to construct a one-good model of an economy and label that good “pencils.” Despite the possibility of modeling such a pencil economy, it is impossible for anyone to set down orders that would lead to the production of pencils (Read 1958). In other words, there is no singular object to which rational expectations pertains. An index of prices, for instance, is not a reasonable object of commercial action. What is a reasonable object of action depends on the particular commercial situation faced by the actor. Someone interested in promoting wind power in South Carolina will adopt different objects at which action aims than someone interested in promoting wind power in Oregon, and with yet different objects of action being relevant to someone exploring development of a new line of breakfast cereals. For policy measures to calm turbulence, they must promote the smoother meshing of plans within the micro ecology of plans where all human action 16 occurs. Such smoother meshing would project onto the macro level as lessened turbulence; however, the work involved in achieving that calming effect is micro and not macro in nature. It is always particular sets of context-related variables at which action aims, with the macro forms of those variables being nothing but delayed accounting constructions. To the extent policy interjections impede relationships within the ecology of plans, policy could create turbulence rather than calm it, as illustrated by policy measures that support activities that turn out to be commercially unprofitable. The success of policy requires that it promote coordination among participants within the ecology, but that coordination cannot be secured outside the nexus of transactions that is illustrated by the emergent order depicted by the lower part of Figure 1. Viennese kaleidics treats an economy not as a machine but as a complex network of interacting people whose relationships are governed through a framework of intersecting and sometimes conflicting rules and conventions. What results is recognition that economic disruption, what are often described as “crises” these days, are endogenous features of normal economic interaction. While that turbulence is generally modest, it need not be. Jane Jacobs (1992) describes society as operating through interaction between carriers of two distinct moral syndromes, which she describes as commercial and guardian. She attributes significance to the architecture of that interaction, claiming that “monstrous moral hybrids” can sometimes evolve out of that interaction. Economists typically work with a universal notion of rationality as conveyed by the proposition that people will make consistent choices. The 17 context of choice is irrelevant for the formal notion of rationality. Yet the content of rational action depends on the context of action, as illustrated by Pierre Bourdieu’s (1990) treatment of the logic of practice. People who harvest oysters of grounds held in private will harvest them differently than people who harvest them on commonly held grounds. On privately held grounds, people will typically return immature oysters along with cultch they dredge up, but this style of harvesting is less likely to be found on commonly held grounds, as Angello and Donnelley (1975) explain. Political economy entails a conjunction of actors, some of whom operate within a framework of private property while others operate within a framework of common or collective property, as Wagner (2007) explores. Different contexts of action will reasonably elicit different choices, as conveyed by Jacobs’s treatment of the two distinct syndromes of action. In a similar vein, Alasdair MacIntyre (1988) distinguishes between rationalities of excellence and effectiveness, a distinction that is explored with great charm by Robert Pirsig (1974). Conflict among people and not harmony among them is a natural accompaniment of the existence of contrasting rationalities of practical action. The root of praxeology is praxis, which locates praxeology as the science that studies the practice of commercial activity. Societies also contain other types of practice, and with each practice there corresponds a logic of practical action. With respect to political economy as a field of study, we are dealing with a relationship between two logics of practical action. While the results aren’t always lovely, they are unavoidable. 18 Different substantive rationalities of practice map into institutional incongruities, as Ludwig Lachmann (1971) explains. In this respect, Maffeo Pantaleoni (1911) treated a society as operating with two inconsistent pricing systems, one a system of market pricing and the other a system of political pricing. The system of political pricing, moreover, was parasitical on the system of market pricing, which meant that the political system needed the market system while at the same time it unavoidably degraded it, and with no presumption of equilibrium in this predator-prey relationship. What comes out of this line of thought is recognition that turbulence is an inherent feature of freedom of action, though the conventions and practices of private property operate to mitigate that turbulence. Viennese kaleidics shows reality to be inherently turbulent, but it also explains how a free people possess the tools to fabricate societal arrangements that can dampen that turbulence. Conflict among plans creates commercial debris, yet that debris is owned by someone under the conventions of private property. Those owners have strong incentive to be realistic in abandoning plans in an effective manner through commercial reorganization. Hence, the debris from a failed plan will typically be distributed to those who value relatively highly the value of that debris as inputs in their commercial plans. In the presence of public ordering, however, the incentive to declare plans to have failed weakens because there is no position of residual claimacy. Public ordering, moreover, can impede the abandonment of commercial plans, as when antitrust prevents the 19 debris from abandoned plans to be sold to those who value that debris most highly. When economists speak of markets, regardless of whether they are pointing to what they regard as success or failure, they tend to think in terms of textbook examples of market adjustment to changing conditions of demand and supply. In some models, markets adjust well and correctly while in other models they don’t. In either case, however, the object that does the adjusting is the market economy that is described in the textbooks. This is the economy that is regulated by private decisions to buy and sell and to produce and to abandon production. This is, in other words, the economic analytics of an institutional framework of private property. This institutional framework, however, is an ideal type of institutional order that is used to illustrate certain properties of an imagined system of social relationships. It is not a framework that actually governs economic transactions and activity. Yes, private ordering plays a role in the organization of economic activity. But in contemporary social democracies, private ordering is only partial. Public ordering is also present. Moreover, and central to the line of analysis pursued here, the two forms of ordering carry with them different rationalities of practical action, just as practical rationalities differ as between harvesting oysters on private and on common property. The requisites for practical action for someone who operates within a framework of private ordering typically differs from those faced by someone who operates within a framework of public ordering. The conflict set in motion by this institutional incongruity can intensify 20 the natural turbulence that characterizes the ecology of plans that comprises an economy. As a purely formal matter, rationality means only that people act consistently in seeking to replace what they value less highly with what they value more highly. As a substantive matter, however, just what it is that provides value and how that value can be attained can differ across settings for action. As Buchanan (1969) explains, the cost of taking one action is represented by the value the chooser places on the option that is rejected in favor of the option selected. If both parties to a dispute are residual claimants to their legal expenses, they have strong incentive to settle disputes rather than going to trial. If one party to a dispute is a public entity, there is no residual to claim. Legal expenses must be spent within the budgetary framework of collective property. Those expenses can be used in different ways, as illustrated by being spread across many smaller trials or concentrated on a smaller number of larger trials. Furthermore, what it is those trials produce for the public agent depends on what the relevant public agent aims to achieve. In this respect, legal expenses can serve as investments in promoting favored causes or possibly running for public office through selecting cases based on some publicity calculus. When Ludwig von Mises (1966: 716-861) referred to an unhampered market economy, he was referring to an imaginary world of wholly private ordering. While this world might have had a good deal of descriptive accuracy in times past, these days public ordering has a presence throughout economic life. Indeed, the very meaning of “market economy” becomes ambiguous in the 21 presence of significant public ordering. With respect to credit transactions, for instance, within a framework of private ordering credit contracts would be between borrower and lender alone. The terms of a contract, including such things as interest rates and provision for repossession, would be wholly between the parties. Moreover, consent between the parties alone would be both necessary and sufficient for credit contracts to be concluded. The aggregate of such credit contracts, along with the various types of vendors engaged in this activity, would constitute what we call the credit market that is assembled through private ordering. Contemporary credit markets do not operate under private ordering; they operate through an admixture of private and public ordering. Private ordering as reflected by agreement between borrower and lender is still necessary for credit contracts to be concluded. But it is not sufficient because credit contracts are also subject to public ordering in numerous ways. One such way is through requirements that lenders must exhibit a portfolio of loans that reflects various distributional requirements that often are rationalized on equity or distributional grounds. In this respect, Moyo (2011) notes that in 1966 Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac required that at least 42 percent of their mortgages were held by borrowers with below-average incomes, and with this share increased to 52 percent in 2005. Moreover, at least 12 percent of those mortgages were to be held by borrowers whose incomes were less than 60 percent of the average in the relevant geographic area. 22 What results is a form of tied sale wherein the price of making loans that would pass muster under private ordering is the acceptance of loans that would not have been made under private ordering. In either case we can speak of a market for loanable funds as an aggregate construction. The composition of that aggregate, however, would differ as between wholly private ordering and an admixture of private and public ordering. To illustrate with a simple bivariate model, suppose potential borrowers are evaluated by lenders as either low risk or high risk. With wholly private ordering, either type of borrower could receive loans at terms agreed on by borrowers and lenders. The market for loanable funds would feature a variety of contractual terms that might be reduced hedonically to the simple aggregate constructions, but the societal work would occur at the micro level where the various contracts are assembled. But credit markets don’t operate through private ordering alone, which means in turn that the composition of credit relationships will change from what it would have been under wholly private ordering. Under private ordering, Ricardian equivalence characterizes each and every contract at the ex ante stage. This equivalence vanishes with public ordering, as there is now a subset of contracts for which borrowers an increase in net worth relative to their situation under private ordering. With respect to Figure 1, public ordering operates on the lower part of that Figure to influence the pattern of credit contracts from what would have emerged under wholly private ordering. Public ordering changes the substantive operation of credit markets in numerous particular ways, one of which entails restrictions on the ability of high risk borrowers to compete with low 23 risk borrowers by restricting the allowable terms of credit contracts and another of which is the imposition of tied-sale requirements where the offer of pricecontrolled contracts to a stipulated number of high-risk borrowers is a condition of doing business. We can still describe credit markets in generic terms through the demand and supply of loanable funds. But the composition of that market, as well as perhaps measures of aggregate size, will vary with the forms of public ordering, thereby yielding different particular projections onto the macro level. Besides leading to a reduction in the overall amount of credit from what would have resulted under wholly private ordering, there will be a shift in the pattern of credit relationships because some volume of credit is now extended to high risk borrowers that would have been extended to low risk borrowers under private ordering. If a subset of credit recipients are now subsidized through regulation, other recipients of credit must provide those subsides through higher prices than they would have paid through wholly private ordering. This tied-sale arrangement presents a problem of how to hold the arrangement together, reflecting what Ikeda (1997) describes as the dynamics of the mixed economy. Collective regulatory agencies operate within a parasitical relationship with commercial entities: they require commercial hosts if they are to ply their regulatory craft, and yet their activities weaken the hosts, which in turn will elicit regulatory efforts to support the faux-market activity of contemporary social democracies. So what we observe is not one more instance of market failure but the dynamic and systemic 24 logic of an admixture of public and private ordering and the conflicting rationalities that this admixture brings. 5. Final Remarks on Kaleidics and Liberty The prime lesson that Viennese kaleidics offers is that a free people who relate to and interact with one another within the institutional framework of private ordering are able to generate a variety of commercial practices and organizations that allow for a flourishing kaleidic society. Kaleidics is a concomitant of liberty, but liberty also allows development of the institutional and organizational tools for bringing kaleidics under reasonable control, as illustrated by people who have made and lost fortunes several times in one lifetime, as well as by the development of organizations and institutional arrangements to facilitate the abandonment as well as the creation of plans. I offer these remarks within the spirit of plausible and not demonstrative reasoning. I make no effort to assert the impossibility that policy can calm turbulence. While I do not doubt the ability of someone to construct a set of axioms that would support such an assertion of impossibility, I doubt that any such axioms command universal assent, any more than Arrow’s (1963) axioms command universal assent. It is, for instance, imaginable even if unlikely that the collection of information from all market participants would allow someone to discern patterns that would not be discerned from the information collected by subsets of market participants. Yet that information would be stale and mostly backward looking, as it would pertain to actions taken yesterday and not to 25 actions contemplated tomorrow. It would also be of a wholly explicit character, eliminating in the process the vital role played by tacit knowledge in the operation of commercial enterprise. Under private ordering, an enterprise that believes it has assembled particularly valuable information must act in a contractual manner with other participants to gain from that assembly, which lends credence to the veracity of that assembled information. Collective entities can compel action and are not residual claimants over the actions they compel, which gives strong reason for doubting the veracity of those claims. We should recognize in this respect that the qualities of information vary with how it is assembled: private ordering works through mutual attraction, in contrast to the compulsion that accompanies public ordering, which surely renders private ordering a higher quality source of information than public ordering, particularly once it is recognized that those who collect information through compulsion are not residual claimants on the actions they might compel based on that information. In short, there is really not much that policy can accomplish to calm the turbulence that is a natural accompaniment of a kaleidic society, aside, that is, from helping in the maintenance of the provisions and conventions of private ordering. A century or so of economic thought has pushed Policy into the foreground as the way to tame kaleidics, as a concomitant of the replacement of what Boettke (2007) describes as the mainline of economic theory with the mainstream. This taming, along with the associated mainstream framework, is sensible only under two circumstances. First, society is simple in character so 26 that turbulence can be tamed by acting on a handful of macro variables. Second, those who operate Policy have both the wisdom and the detachment to execute what the simple models would seem to require. Neither circumstance fits the conditions of modern life. Macro variables cannot be acted upon directly. They can be affected only indirectly through action that is injected at particular points within the ecology of plans, with macro-level consequences emerging through the resulting interactions. Just because Keynes embraced the presuppositions of Harvey Road, at least according to Harrod (1951), does not mean that this embracement was on the mark. Whatever distance from the target it might have been back then, it is surely farther from the target in our present times. It is not private ordering in the governance of economic activity that we should fear in our kaleidic society; rather it is the use of public ordering to trump and warp what would otherwise have been the accomplishments of private ordering. Viennese kaleidics cannot prophesy the future, for no theory can do that, but it can explain how a constitution of liberty, as distinct from a constitution of servility, allows through private ordering the generation of institutions and organizations that render kaleidic reality interesting and adventuresome and not worrisome or frightening. 27 28 References Aligica, P.D. and P.J. Boettke. 2009. Challenging Institutional Analysis and Development: The Bloomington School. London: Routledge. Angello, R. J. and L. P. Donnelley. 1975. “Property Rights and Efficiency in the Oyster Industry.” Journal of Law and Economics 18: 521-33. Arrow, K. J. 1963. Social Choice and Individual Values, 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley. Boettke, P. J. 2007. “Liberty vs. Power in Economic Policy in the 20th and 21st Centuries.” Journal of Private Enterprise 22: 7-36. Bourdieu, P. 1990. The Logic of Practice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Bowles, S. and H. Gintis. 1993. “The Revenge of Homo Economicus: Contested Exchange and the Revival of Political Economy.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 7: 83-102. Buchanan, J.M. 1969. Cost and Choice. Chicago: Markham. Clower, R. W. 1994. “Economics as an Inductive Science.” Southern Economic Journal 60: 805-14. Clower, R. W. 1995. “Axiomatics in Economics”. Southern Economic Journal 62: 307-19. Clower, R. W. and Leijonhufvud, A. 1975. “The Coordination of Economic Activities: A Keynesian Perspective.” American Economic Review, Proceedings, 65: 182-88. Gloria-Palermo, S. 1999. The Evolution of Austrian Economics: From Menger to Lachmann. London: Routledge. Harrod, R.F. 1951. The Life of John Maynard Keynes. London: Macmillan. Hayek, F. A. 1932. Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle. New York: Harcourt Brace. Ikeda, S. 1997. Dynamics of the Mixed Economy. London: Routledge. Jacobs, J. 1992. Systems of Survival. New York: Random House. 29 Keynes, J. M. 1936. The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. New York: Harcourt, Brace. Keynes, J. M. 1937. “The General Theory of Employment”. Quarterly Journal of Economics 51: 209-23. Koppl, R. 2001. “Alfred Schütz and George Shackle: Two Views of Choice.” Review of Austrian Economics 14: 181-91. Lachmann, L.M. 1971. The Legacy of Max Weber. Berkeley, CA: Glendessary Press. Lachmann, L, M. 1976. "From Mises to Shackle: An Essay on Austrian Economics and the Kaleidic Society.” Journal of Economic Literature 14: 54-62. Leijonhufvud, A. 1968. On Keynesian Economics and the Economics of Keynes. New York: Oxford University Press. Leijonhufvud, A. 1981. Information and Coordination. New York: Oxford University Press. MacIntyre, A. 1988. Whose Justice? Which Rationality? Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press. Menger, C. 1871 [1981]. Principles of Economics. New York: New York University Press. Menger, C. 1883 [1985. Investigations into the Method of the Social Sciences. New York: New York University Press. Mises, L. von. 1966. Human Action, 3rd ed. Chicago: Henry Regnery. Moyo, D. 2011. How the West Was Lost. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. O’Driscoll, J. P. and M. J. Rizzo. 1985. The Economics of Time and Ignorance. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Ostrom, V. (1996). Faustian bargains. Constitutional Political Economy 7: 30308. Pantaleoni, M. 1911. “Considerazioni sulle proprieta di un sistema di prezzi politici.” Giornale degli Economisti 42: 9-29, 114-33. Parsons, S. D. 1993. “Shackle, Nihilism, and the Subject of Economics.” Review of Political Economy 5: 217-35. 30 Pirsig, R.M. 1974. Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values. New York: William Morrow. Polya, G. 1954. Mathematics and Plausible Reasoning, 2 vols. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Read, L. 1958. I, Pencil. Irvington-on-Hudson: Foundation for Economic Education. Rothbard, M. N. 1990. “The Hermeneutical Invasion of Philosophy and Economics.” Review of Austrian Economics 3: 45-59. Salerno, J. T. 2002. “The Rebirth of Austrian Economics—In Light of Austrian Economics.” Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 5: 111-28. Samuels, W. J. 1993. “In (Limited but Affirmative) Defense of Nihilism.” Review of Political Economy 5: 236-44. Shackle, G. L. S. 1972. Epistemics & Economics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Shackle, G. L. S. 1974. Keynesian Kaleidics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Wagner, R. E. 2007. Fiscal Sociology and the Theory of Public Finance. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. Wagner, R. E. 2010. Mind, Society, and Human Action: Time and Knowledge in a Theory of Social Economy. London: Routledge. Wagner, R. E. 2012. Deficits, Debt, and Democracy: Wrestling with Tragedy on the Fiscal Commons. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. Wagner, R.E. Forthcoming. “A Macro Economy as an Ecology of Plans.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. Yeager, L. B. 1997. “Austrian Economics, Neoclassicism, and the Market Test.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 11: 153-65. 31