ISA Roundtable - University of South Carolina

advertisement

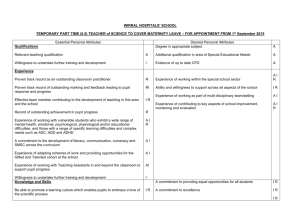

“Necessity, Counterfactuals, and Substitutability: Looking at the Wave of Islamic Revolutions” Harvey Starr Department of Political Science University of South Carolina Roundtable Working Paper prepared for the Roundtable, “Counterfactual Analysis and Post-9/11 U.S. Foreign Policy,” for presentation at the Annual Meeting of the International Studies Association, April 4, 2012, San Diego, CA. Given my career-long concern with contexts and the Sproutian ecological triad, and especially the conditionality of theory—under what conditions will a theory hold, and thus how “contending” theories could both be correct (see Most and Starr 1989)—my career has had a major focus on necessary conditions and, thus, on counterfactuals. It has been about the crucial place of theory when thinking in a counterfactual way, how counterfactuals are linked to causes, and how we can explore/validate such counterfactuals (for the lattermost point, see Levy 2008). Theory is crucial for identifying the key conditions, variables, or events (meaning primarily the types of events) that could have altered outcomes by their presence or absence. That is, following Isiah Berlin (1955), counterfactuals had to be plausible, and with some reasonable probability of occurring. This is, then, one very useful function of Charles Ragin’s Boolean truth table approach (QCA)—using extended or macro-case studies to generate a set of plausible factors (or, in Ragin’s terms, “causal conditions”). In addition, we also need to think about the factors/alternatives that were perceived as plausible at the time by decision makers and their audiences/constituents, and not some incredible outlier that only one/few people suggested, such as alien activity!1 Again, we need theory to find the conditions/factors/events which represent parts of categories, functions, or broader concepts. That is, regarding short term causes we may look for “triggers,” or “shocks.”2 We might be looking for broader concepts, factors or conditions such as those that represent “opportunity” or “willingness.” Theory will lead us to argue that these things are necessary, and thus, without them, other events or phenomena will not occur. This has been my position on the jointly necessary conditions of opportunity and willingness since Starr (1978). As a side note, Berlin was concerned with counterfactuals as one way to combat determinism is the study of history. As I have noted in a number of places, the work of Harold and Margaret Sprout, and their idea of the ecological triad (entity, environment, and entity-environment relationship) was foundational to the development of the opportunity and willingness framework. Like Berlin, the Sprouts’ development of the ecological triad, and their concern with “man-milieu” relationships, was their way to attack determinism in geopolitics! While complicating some matters considerably, the phenomenon of “substitutability” in dealing with necessary (and sufficient) conditions, also works strongly against deterministic approaches. If, as argued and demonstrated in Cioffi-Revilla and Starr (1995), opportunity and willingness are jointly necessary (and thus make any action more difficult to achieve or occur), then substitutability works to increase the probability of the presence of either opportunity 1 Levy (2008) notes that necessary condition counterfactuals should have specified antecedents and consequents to be useful in teasing out the implications of the counterfactual. 2 Levy (2008) also notes that counterfactuals are central to such approaches as “powder keg” models (Goertz and Levy 2007), “window of opportunity models” (Kingdon 1984), or path dependency and critical junctures explanations (Mahoney 2000). and/or willingness, and thus make some action easier to occur. It does so by identifying a whole set of conditions that might individually (or in combination) be sufficient to generate opportunity and/or willingness. If a model argues that we need opportunity—such as the short term or immediate factor of a trigger—that trigger might take any one (or combination) of forms, any one of which would be sufficient to be a “trigger” and thus provide the opportunity. Let’s look at this another way. As noted in Starr (2011), necessary relationships often take the form of counterfactuals, especially in case studies focusing on explaining individual events. The necessity relationship claims that only if X can there be Y. The counterfactual claim holds that without X, if X had not happened, Y would not have occurred.3 Substitutability may be about different paths to the same outcome, that is, different sets of contingent conditions. Indeed, in many cases, contingency is expressed as a necessary condition, without which some effect, outcome, or other dependent condition could not occur. This is why necessity is a key component of a philosophical view of causality becoming more and more prominent—the INUS view of causation. An INUS explanation is an “Insufficient but Nonredundant [i.e., necessary] part of an Unnecessary but Sufficient condition,” for which Mahoney and Goertz (2006, p. 232) provide a succinct explanation: An INUS cause is neither individually necessary nor individually sufficient for an outcome. Instead it is one cause within a combination of causes that are jointly sufficient for an outcome. Thus, with this approach, scholars seek to identify combinations of variable values that are sufficient for outcomes of interest. The approach assumes that distinct combinations may each be sufficient, such that there are multiple paths to the same outcome. Research findings with INUS causes can often be formally expressed through Boolean equations such as Y = (A AND B AND C) OR (C AND D AND E). The logic of necessity and sufficiency, and multiple causal paths, may thus be clearly captured by Boolean logic and methods (most fully introduced in the work of Ragin). The conjunctive Boolean AND denotes necessary conditions. Thus, in the above equation, A, B, and C are all necessary conditions in combination, to be sufficient for Y. But note, so are C, D, and E in combination. The Boolean disjunctive OR indicates that either of these two combinations is sufficient for Y—multiple paths to the same outcome. The reader should note that the philosophy of science dealing with concepts holds a similar position—that a good definition of a concept is one with necessary conditions that are jointly sufficient. In essence this is the mirror image of what Cioffi-Revilla and Starr do with opportunity and willingness (as noted above): opportunity and willingness are jointly necessary, but through substitutability, there are multiple paths or factors sufficient to produce either opportunity or willingness. Thus, combinations of necessary factors may be sufficient for an 3 Goertz and Levy (2007) contrast a necessary-conditions counter-factual approach (looking for necessary conditions within individual cases) with a nomological covering-law approach (based on the constant conjunction of covering laws stated and tested with large-n statistical/probabilistic methods). outcome; combinations of sufficient factors (two or more, or even one) can produce a necessary condition. Cioffi-Revilla and Starr (1995) explicitly look at a (highly implausible) counterfactual world: one where only one broad factor, be it opportunity or willingness, is necessary for an event to occur. This would mean if an opportunity were present some event would occur (regardless of willingness); or if willingness were present some event would occur (regardless of opportunity, including capabilities). They discuss the bizarre world that would exist under such implausible conditions. Oakes (forthcoming), however, without using these exact terms, does link different conditions to “thought experiments” [counterfactuals] regarding the presence or absence of necessary or sufficient conditions to foreign policy decision making. Her argument is that contingencies or environmental conditions may eliminate options or choices from the “menu” of a decision maker. Oakes notes: “These external factors can be critically important causes of the final policy decision in two scenarios. The first situation is where an environmental constraint removes an option that a leader would have preferred to the final decision. In other words, variable X removes policy A, and so the leader pursues substitute policy B. Here, the constraint may be a necessary condition for the decision. In a counterfactual, if that variable had been absent, the leader would have had a broader menu of available policies and would have chosen differently. “ Thus, Oakes provides another twist: necessary conditions can affect choices by removing potential choices as well as adding them to the list of alternatives! Oakes then outlines one way to use counterfactuals: “To explain government decision making then, we must perform a thought experiment. First, we consider the leader’s ranking of the policy alternatives in a ‘perfect world,’ one absent environmental constraints. Second, we reintroduce these constraints and determine whether they eliminate (or enable) certain alternatives.” Here, we need to look at both preferences and constraints (that is opportunity and willingness, and how they affect the “menu for choice”; e.g. Russett and Starr 1981). As Oakes argues, this is a difficult task: “Where environmental constraints rule out a particular option on the policy menu, leaders may never discuss that policy at all. Nevertheless, it should appear in our “perfect world” ranking, and could even be in first position: a decision maker might have pursued this avenue if the constraints had not existed. Thus, we may have to rely on counterfactuals and circumstantial evidence to build a case for what a leader’s preferred policies would have been.” As with the study of deterrence, we have to deal with behavior that does not occur.4 Revolution in the Islamic World From the end of 2010 through the first months of 2011, my first impulse, of course was to think in terms of diffusion as a necessary factor (through contiguity or neighborhoods) in the growth and spread of anti-regime revolutions. Taking events starting in December 2010 up to February 4 In the Cuban Missile Crisis, for example, the lack of an existing (bureaucratic) plan for a “surgical strike” against targets in Cuba, removed this option almost immediately from the ExComm discussions 23, 2011, I looked for the spread of protest along temporal (chronological) lines; that is Tunisia to Egypt, then Egypt to Iran, then Iran to Yemen and Libya, etc. From 10 possible dyads, only 2 displayed positive spatial diffusion or contagion through contiguous borders. Still, a timeline existed from Tunisia to Egypt, which precedes Libya, which precedes Algeria, which precedes Morocco. However, this approach assumes that all the states involved, or in the region, were equally “ready” for protest, etc.—an unrealistic or implausible assumption. So, just looking to see if the countries involved had contiguous borders with any of the others, I found that 8 of those countries had a contiguous border with at least one other of these countries. A key point to note is that Libya had borders with Tunisia and Egypt– both of which not only held protests but deposed long standing rulers.5 As there is not clear evidence of positive spatial diffusion, we are led back to the usual question: is what appears to be the “spread” of some phenomena the result of positive spatial diffusion or simply “clustering”? Clustering is based on the units under consideration having similar profiles or factors, and thus could possibly “react similarly, but independently to similar domestic conditions” (Elkins and Simmons 2005, 34), or as noted by Starr, et al. (2008), clustering can also be seen as “uncoordinated interdependence.” By investigating clustering we might uncover a factor (or several in combination), which might be necessary for the occurrence of revolution in a set of countries. Since diffusion may involve simply some form of “demonstration effect” or “emulation”6 (instead of, or as well as, spatial contagion) we would have to take a demonstration effect seriously, and look at the impact of current communication/social network technology as a key factor (one possible component of Rosenau’s “microelectronic revolution” [1990]). Perhaps a demonstration effect could be combined with other aspects of clustering into a broader “regionalism” phenomenon. Clustering assumes that the units share a number of similar factors. These states generally share many societal and historical factors: non-democracies; long term autocratic rulers; language, and religion; as well as a general spatial proximity. Is regionalism the necessary condition? If so, does it require all of these (substitutable) factors that would identify a cluster, or are any of these by themselves sufficient to produce the necessary condition of regionalism? Would the group of revolutions not have occurred without any or all of these “regional” factors? 5 I used: Tunisia, Egypt, Iran, Yemen, Bahrain, and Libya. Also, given the protests that occurred over the weekend of February 19-20, 2011 I also included Morocco, Algeria, Oman, Kuwait, and Djibouti. (I added Iraq on February 25.) 6 Emulation may also force us to think of short-term triggers, shocks or various “punctuated equilibrium” models-- that posits a “shock” can cause cascading change in interdependent systems. Here, the “shock” could be the forcing Tunisian President Ben Ali to flee the country. As noted in the sub-headline in a CNN story (February 23): “The fear wall broke...” Many analysts argued that this event encouraged emulation. Or, is regionalism only one of two necessary components? Perhaps there are major systemic factors as well during this time period that could be seen as necessary, in that they are “permissive” in permitting the Islamic revolutions to occur. As compared to the revolution from below that ousted the Shah of Iran in 1979, all these events are now occurring in a postCold War world, without opposed superpowers which would move to support governments they favored against protest/revolt, or, who would oppose the other superpower’s use of force to help a government or an opposition. Without such superpower support, many autocratic governments have become more vulnerable. However, where such a threat to a regime took place also raised a set deterrent threats between the US and USSR. If the US or NATO had sent forces to defend the Shah in 1979—in a country bordering the USSR-- we can suppose (a counterfactual!) that the Soviet response would have been intense, and it could be argued deterred such US/NATO action. In a non-Cold War context, NATO could send forces to support Libyan rebels without similar military support going to Gaddafi (as occurred in Indochina), or in the run-up to war (e.g. US and Soviet arms support to the states in the Middle East). There is also the reverse: the growth in the number of democracies, and the growth and spread of democratic/liberal norms (such as human rights) throughout the system including the roles of IGOs and NGOs. Democratic norms include a clear 21st century external disapproval of, and much less tolerance of, the use of massive governmentally organized fatal violence against their own people (what Rummel has termed “democide”; e.g. see 1995). The upshot of all this is that governments may/should be much less likely to use force, or to be able to get their armies to kill their fellow citizens. Note that Qaddafi to a large extent, especially early on, relied upon foreign mercenaries, while his air force pilots defected. Also, Libyan rebels were provided extensive air and sea power by NATO to aid their cause. I think this is a useful set of factors for comparing the 2010-2011 (and the current Syrian problems) to previous revolutions, such as Iran in 1979. Counterfactual claims can be tested against conditions in Iran in 1979. Two prominent models focus on an alternative explanation, the presence or absence of what Bueno de Mesquita and Smith (e.g. 2011) call “free goods,” or Girod (2012) terms “windfall profits.” Governments that can raise revenue from these sources, it may be argued, are more likely to hold together their winning coalitions, and either prevent revolution or emerge victorious. Bueno de Mesquita and Smith note that such goods, are “free” in the sense that “relatively little labor is needed to generate wealth and added revenue can be achieved with these resources without having to raise taxes on labor.” However, in the 1970s the Shah was being provided with extensive free goods/windfall profits, as was the contemporary example of Gaddafi in Libya. My bottom line feeling is that a set of necessary conditions would include, (1) a successful “shock” that could be (2) emulated by relatively proximate countries (regionalism) in (3) a world system where a set of permissive factors would allow and encourage revolution. This brief counterfactual story takes substitutability into account within an INUS structure—arguing that a set of necessary conditions produces a sufficient cause for revolution (or perhaps several different combinations of necessary causal conditions). REFERENCES Berlin, Isiah. 1955. Historical Inevitability. New York: Oxford University Press. Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce and Alastair Smith. 2011. “Predicting Revolution with Emphasis on the Middle East.” Paper presented at the conference, “New Perspectives in Conflict System Analysis: Applications to the Middle East,” University of South Carolina, Columbia, October 2830, 2011. Girod, Desha. 2012. “Regime Survival and Development Without Institutions: The EmptyPockets Coup-Proofing Hypothesis.” Paper presented at the Political Science Research Workshop, University of South Carolina, Columbia. Goertz, Gary and Jack Levy. 2007. “Causal Explanation, Necessary Conditions, and Case Studies.” In G. Goertz and J. Levy, eds. Explaining War and Peace: Case Studies and Necessary Condition Counterfactuals. New York: Routledge. Kingdon, John. 1984. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. Boston: Little, Brown. Levy, Jack S. 2008. “Counterfactuals and Case Studies.” In J. Box-Steffensmeier, H. Brady, and D. Collier eds. Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology. New York: Oxford University Press. Mahoney, James. 2000. “Path Dependence in Historical Sociology.” Theory and Society 29: 507548. Mahoney, James and Gary Goertz. 2006. “A Tale of Two Cultures: Contrasting Quantitative and Qualitative Research.” Political Analysis 14: 227–249. Oakes, Amy. Forthcoming. Diversionary War: The Link Between Domestic Unrest and International Conflict (Stanford: Stanford University Press). Rosenau, James N. 1990. Turbulence in World Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Rummel, Rudolph. 1995. "Democracy, Power, Genocide, and Mass Murder," Journal of Conflict Resolution 39: 3-26. Russett, Bruce and Harvey Starr. 1981. World Politics: The Menu for Choice. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. Starr, Harvey. 1978. “’Opportunity’ and ‘Willingness” as Ordering Concepts in the Study of War.” International Interactions 4: 363-387. Starr, Harvey. 2011. “Conditions, Necessary and Sufficient.” In Bertrand Badie, Dirk BergSchlosser, and Leonardo Morlino eds. International Encylcopedia of Political Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Starr, Harvey, David Darmofal, and Zaryab Iqbal. 2008. “Civil War: Spatiality, Contagion, and Diffusion.” Paper presented at the conference, “The Spatial and Network Analysis of Conflict,” (Program in Arms Control, Disarmament and International Security and the Department of Geography), University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana, September 25-27, 2008.