6. Executive Summary - Documents & Reports

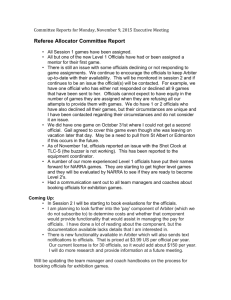

advertisement