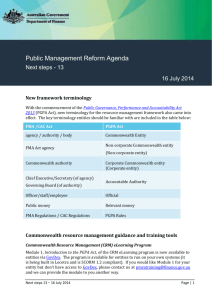

Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Bill 2013

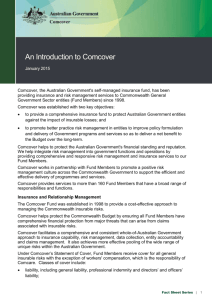

advertisement