Analyzing arguments

advertisement

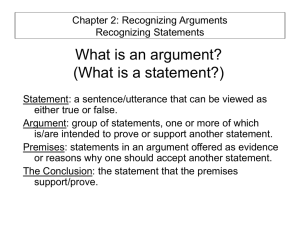

Analysis of arguments During the course we have worked with the analysis of arguments. Analyzing an argument means breaking it down into its component parts so the structure of the argument becomes clear. Finding the structure of an argument is a prerequisite to evaluating whether or not it’s a good argument, i.e., deciding if we are justified in accepting the conclusion on the strength of the premises. The basic components of arguments are premises and conclusions. The technique we have used for finding structure is to first identify premises and conclusion and then attempt to fit these into one of the six basic deductive patterns, or a combination of them, in the texts we have examined. After reconstructing the argument to fit into a valid pattern, being charitable and possibly providing implicit premises, we try to determine whether the argument is also sound. This part of the analysis might involve reconstructing the argument as an inductive argument. If that is the case the argument is no longer deductively valid but could still be inductively successful if the premises provide evidence that render the conclusion probable. When dealing with actual arguments certain argumentative strategies are more common than others. Each strategy can often be associated with a type of standard pattern. The following is meant as “rules of thumb” in recognizing these common strategies. When somebody wishes to present an argument against a certain position, proposal or plan some version of the modus tollens pattern is often used. The strategy is simple: you attempt to show that the proposal or plan being discussed will lead to undesirable consequences and therefore should be rejected. Or, if one is arguing against a specific course of action, one shows that the expected results won’t follow from that action. An example would be Rideau’s argument from his essay about prison reform: 1) IF stiff prison sentences work as a deterrent THEN Louisiana should be safe. 2) Louisiana is not safe. So: Stiff prison sentences don’t work as a deterrent Another example would be a reconstruction of Shanker’s argument in the article about pseudo education. Shanker outlines a chain of consequences that follow from the prevalence of pseudoeducation: 1) IF pseudo education is practiced THEN the quality of science, arts, and government will suffer. 2) IF so, THEN the country can’t remain competitive in a global economy 3) But, we want to remain competitive! (implicit) So: we must curb pseudo education The modus tollens pattern is also used to show that a scientific theory or hypothesis should be rejected or modified. One deduces a consequence or prediction from the theory and shows it to be false. Here is an example due to Fred Hoyle (the astro physicist the space telescope is named after): If the universe was infinitely old, there would be no hydrogen left in it, since hydrogen is steadily converted into helium throughout the universe, and this process is a one way process. But, in fact, the universe consists almost entirely of hydrogen. Thus the universe must have had a definite beginning. All of these examples are versions of the modus tollens pattern and they follow the same basic strategy. However, there are some common variations of this strategy worth knowing about. Often people use “dilemmas” in debates in combinationwith the modus tollens strategy. Here is an example: 1) If we invest to develop the Stars Wars defense system THEN it will EITHER become successful and be deployed as part of our nuclear missile defense shield OR it will be ineffective because of technological problems. 2) IF it is successfully deployed THEN the enemy will build more advanced systems to counteract it and there is no tactical advantage 3) IF the system is ineffective THEN it’s a massive waste of money 4) IF we invest in Star Wars THEN it’s EITHER a waste of money OR there is no advantage 5) Both a waste of money and no advantage are unacceptable So: we shouldn’t invest in the Star Wars missile defense system The point is that either way it’s a bad idea. A similar strategy can be used to show that a proposal has a “Catch 22”, a situation where a plan backfires or defeats its own purpose. One of Shanker’s arguments against vouchers can be reconstructed along those lines: 1) IF a voucher plan is proposed THEN vouchers will go exclusively to children in public schools OR they will be given to all children 2) IF vouchers go to children in public schools only THEN the wealthy parents of children in private schools won’t support it. 3) IF that’s the case THEN the proposal will be defeated 4) IF vouchers go to everybody THEN you have to either increase taxes or make cut funding for public schools. 5) IF that’s the case THEN the proposal will be defeated. So: IF a voucher plan is proposed THEN it will be defeated (in other words, a proposal for vouchers will never fly politically). The overall pattern that is used here is a hypothetical syllogism combined with a modus tollens pattern and a disjunctive pattern. The conclusion that is reached is that IF vouchers are proposed THEN they will be defeated, the voucher proposal will defeat its own purpose (formally this can be expressed IF p THEN not p, from which you can infer that not p is true, a strategy known as reduction ad absurdum.) When you’re trying to argue in favor of a proposal, you often employ an argument of the “only game in town variety”. This strategy is essentially an eliminative one. One argues for a specific course of action by showing that all the other alternatives (the other candidates) are unacceptable. The simplest form of this argument is a disjunctive pattern. We must choose between candidate A or B. Candidate A is no good. Hence, we must choose candidate B. Often this strategy will involve a combination of a disjunction and a modus tollens pattern since you wish to reject all the alternatives except one. Imagine you have 3 serious candidates for healthcare reform: 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) 7) We have to choose EITHER plan A OR plan B OR plan C IF plan A THEN the deficit will increase dramatically This is unacceptable Reject plan A IF plan C THEN it will leave a large number of people without health insurance This is unacceptable Reject plan C So: accept plan B Whether or not such a strategy is successful depends on two factors: you have to make sure that you have considered all the viable options, and you have to be justified in rejecting the other alternatives as out of bounds. Another common form of argumentation consists in defining goals and the means to achieve them. Once the goal has been set, on can define the means of accomplishing it. This can take the form of a standard definition (conceptual theory) where you list a set of individually necessary and jointly sufficient conditions. The strategy is simple, you point out that in order to obtain the goal a number of necessary conditions must be met, and if all of them are met it will be sufficient for obtaining the goal. I have reconstructed such an argument from one of the former Soviet president, Gorbachev’s speeches: The communist party will be successful in the future IF AND ONLY IF (iff) we take the following steps: i) break away from the authoritarian-bureaucratic system ii) become a constitutional democracy iii) give up on centralized plan economy and iv) open up a dialogue with the West. In other words, IF we don’t meet all the conditions THEN we will fail and IF we do meet the conditions THEN we will be successful. Often definitional theories are used for conceptual analysis and clarification of meaning but they can also be used in this more practical way to define a game plan by listing the criteria for success and failure. Many arguments simply point out what the consequences of a certain policy will be or how one thing will lead to another. Often this will take the form of a series of causes and effects (or conditions) that are linked together (conditional chains where one thing depends on another). Typically this strategy involves some sort of chain pattern or hypothetical syllogism: 1) IF you push the button THEN the light will come on 2) IF so, it will trigger the alarm 3) IF so, THEN the whole neighborhood will wake up So, IF you push the button THEN you will wake up the whole neighborhood Just remember that a chain isn’t stronger than its weakest link and that chain arguments sometimes become slippery slopes. Applications to writing argumentative essays. The analysis of arguments is very useful when it comes to writing coherent papers with a clear logical structure. It can help you to outline the paper and serve to make it easier for your audience to follow your train of thought. A lot of college writing involves a critical response to the arguments of others. In these types of assignment it is straightforward to apply the six step procedure (p. 304). Make it a habit to use the procedure to identify and evaluate the arguments you are discussing. Once you have identified the arguments you can structure your own response around the evaluation of the argument. Sometimes the critical discussion of each premise will break down neatly into paragraphs with topic sentences and a conclusion. If so, you have an outline of your paper that it’s easy to follow. At this point a substantial part of your work is done already. When you have to write an essay on a general topic where you have to develop your own arguments for or against something there is no cookie-cutter recipe you can follow. However, the critical thinking skills you have learned can still be very useful when you have to invent your own arguments. First you might consider whether you can use one of the common strategies described here to present your argument. If you follow one of those strategies as a general outline you will have a logical framework that gives you a game plan. Most of the work will consist in presenting evidence to back up the individual premises in order to convince you audience to accept them. In most interesting and controversial arguments you won’t be able to rely exclusively on deductive reasoning. The deductive pattern will provide the overall structure, but the sub-arguments you present for the individual premises will often rely on inductive reasoning and definition of terms as well. If you organize your essay in this way you automatically achieve two things: 1) you have a clear organization of your line of argumentation that will make for a coherent paper, 2) if you manage to present reasons that will make people accept your premises, then you will have an argument that is convincing because it is both valid and sound, one that your audience ought to accept. Just remember the best way of making your argument compelling is to discuss the most obvious objection to it up front. This will usually take the form of defending the individual premises that make up the argument against counterexamples and other objections.