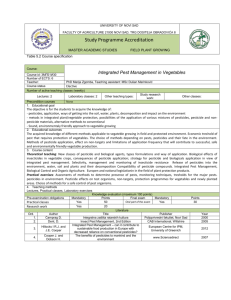

contents - Documents & Reports

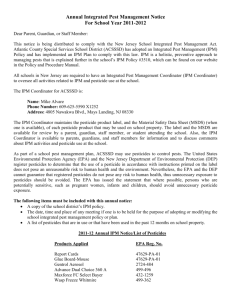

advertisement